Online Chapter B Introduction to Trade Unions, Status, Listing, and Independence and Members' Rights and Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore Labor Rights May 28

Labor Rights Report: Singapore Pursuant to section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act of 2002, the Secretary of Labor, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the United States Trade Representative, provides the following Labor Rights Report for Singapore. This report was prepared by the Department of Labor. Labor Rights Report: Singapore I. Introduction This report on labor rights in Singapore has been prepared pursuant to section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act of 2002 (“Trade Act”) (Pub. L. No. 107-210). Section 2102(c)(8) provides that the President shall: In connection with any trade negotiations entered into under this Act, submit to the Committee of Ways and Means of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Finance of the Senate a meaningful labor rights report of the country, or countries, with respect to which the President is negotiating. The President, by Executive Order 13277 (67 Fed. Reg. 70305), assigned his responsibilities under section 2102(c)(8) of the Trade Act to the Secretary of Labor, and provided that they be carried out in consultation with the Secretary of State and the United States Trade Representative. The Secretary of Labor subsequently provided that such responsibilities would be carried out by the Secretary of State, the United States Trade Representative and the Secretary of Labor. (67 Fed. Reg. 77812) This report relies on information obtained from the Department of State in Washington, D.C. and the U.S. Embassy in Singapore and from other U.S. Government reports. It also relies upon a wide variety of reports and materials originating from Singapore, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). -

Uganda Labour Market Profile 2019

LABOUR MARKET PROFILE 2019 Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Analytical Unit Uganda Danish Trade Union Development Agency Uganda Labour Market Profile 2019 PREFACE The Danish Trade Union Development Agency (DTDA) The LMPs are reporting on several key indicators within is the international development organisation of the the framework of the DWA and the SDG8, and address Danish trade union movement. It was established in 1987 a number of aspects of labour market development such by the two largest Danish confederations – the Danish as the trade union membership evolution, social dialogue Federation of Trade Unions (Danish acronym: LO) and and bi-/tri-partite mechanisms, policy development and the Danish Confederation of Professionals (Danish legal reforms, status vis-à-vis ILO conventions and labour acronym: FTF) – that merged to become the Danish Trade standards, among others. Union Confederation (Danish acronym: FH) in January Main sources of data and information for the LMPs are: 2019. By the same token, the former name of this organisation, known as the LO/FTF Council, was changed As part of programme implementation and to the DTDA. monitoring, national partner organisations provide annual narrative progress reports, including The outset for the work of the DTDA is the International information on labour market developments. Labour Organization (ILO) Decent Work Agenda Furthermore, specific types of data and information (DWA) with the four Decent Work Pillars: Creating relating to key indicators are collected by use of a decent jobs, guaranteeing rights at work, extending unique data collection tool. This data collection is social protection and promoting social dialogue. The done and elaborated upon in collaboration overall development objective of the DTDA’s between the DTDA Sub-Regional Offices (SRO) and interventions in the South is to eradicate poverty and the partner organisations. -

SIU-Crewed Pomeroy Delivered Watson-C1q,Ss ·LMSR Augments American S!!Alift Capacity

Volume 63, Number 9 SIU-Crewed Pomeroy Delivered Watson-C1q,ss ·LMSR Augments American S!!alift Capacity . J~ Photo by National Steel and Shipbuilding Co. Construction Continues on RO/RO Steward Dept. Seafarers To Crew USNS Benavidez The first of two roll-on/roll-off ships for SIU-contracted Totem Ocean Trailer Express, Inc. is under construction in San Diego. It is scheduled for delivery in October 2002. For more photos of the early stages of the construction, see page 3. Seal aring Life Agrees With Zepedas SIU members will soon cl imb the gangway to the USNS Benavidez Three Generations Find Career Niche in SIU (T-AKR-306), which recently was christened in New Orleans. Page 3. House Okays ANWR Recertified Bosun Johnny Zepeda (left) and his son Felipe, who is enrolled in the unlicensed apprentice program at the Paul Development Hall Center for Maritime Training __________ Page 5 and Education, aren't the only ones in their family to discover - their calling through the SIU. Page 9. Carter Investigation Continues __________ Page 2 President's Report Ship Fire Investigation Time Is Right for ANWR Fluctuating gas prices at the pump. Electrical bills skyrocketing. Roving blackouts. The cost of home heating oil inflating. Is it any wonder that the =--.,.._..,,, House of Representatives last month passed-with Still In Early Stages bipartisan support-an energy bill that will affect all Americans? The U.S. Coast Guard in late July began its for from a commercial cargo vessel to an ammunition Besides other benefits, the president's energy plan mal investigation into the engine room fire aboard ship. -

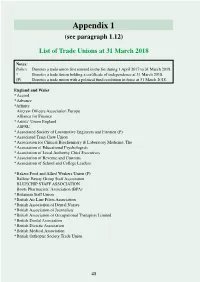

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

What Is Acas?

Ask Acas - Trade Union Recognition What is Acas? Acas is an independent public body which seeks to: • prevent or resolve disputes between employers and their workforces • settle complaints about employees’ rights • provide impartial information and advice • encourage people to work together effectively. What is the Acas role in trade union recognition? Acas can: • give impartial and confidential information and advice on trade union recognition • help resolve disputes over trade union recognition by voluntary means • help resolve disputes when a union makes a claim for statutory trade union recognition • assist with membership checks and ballots to help resolve trade union recognition issues • assist employers and trade unions to draw up recognition and procedural agreements and work together to solve problems. What is trade union recognition? A trade union is “recognised” by an employer when it negotiates agreements with employers on pay and other terms and conditions of employment on behalf of a group of workers, defined as the ‘bargaining unit’. This process is known as ‘collective bargaining’. A trade union may seek recognition in an organisation by voluntary or statutory means. Voluntary trade union recognition When a union uses voluntary means to get recognition, it will contact the employer without using any legal procedures. Acas can help if both parties agree. Statutory trade union recognition Where do unions apply? • An independent trade union may make an application to the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC) for recognition in organisations that employ at least 21 workers. What requirements have to be met before the CAC can consider an application from a trade union? • The trade union must first have made a formal application to the organisation concerned. -

Official Bulletin

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE OFFICIAL BULLETIN Vol. LXVIII, 1985 Series B, No. 1 Report of the Committee on Freedom of Association (238th Report) 238th REPORT Paragraphs Pages Introduction 1-38 1-12 Cases not calling for further examination 39-93 13-30 Case No. 1232 (India): Complaint presented by the BOGL Employees' Unity Centre, the MAMC Employees' Unity Centre and the Small Industries Workers' Union against the Government of India . 39-48 13-15 The Committee's conclusions 45-47 15 The Committee's recommendation 48 15 Case No. 1249 (Spain): Complaint presented by the Federation of Associations of Senior Public Servants' Bodies against the Government of Spain 49-74 15-24 The Committee's conclusions 67-73 22-24 The Committee's recommendation 74 24 u i I3IIJ li 53992 Paragraphs Pages Case No. 1286 (El Salvador): Complaint presented by the Committee of Trade Union Unity of El Salvador against the Government of El Salvador 75-82 25-27 The Committee's conclusions 79-81 27 The Committee's recommendation 82 27 Case No. 1312 (Greece): Complaint presented by the International Transport Workers' Federation against the Government of Greece 83-93 28-30 The Committee's conclusions 91-92 30 The Committee's recommendation 93 30 Cases in which the Committee has reached definitive conclusions 94-172 30-49 Case No. 1007 (Nicaragua): Complaint presented by the International Organisation of Employers against the Government of Nicaragua 94-105 30-33 The Committee's conclusions 101-104 32-33 The Committee's recommendations 105 33 Case No. 1276 (Chile): Complaint presented by the World Federation of Trade Unions against the Government of Chile 106-118 34-36 The Committee's conclusions 114-117 35-36 The Committee's recommendation 118 36 Case No. -

Trade Union Recognition Agreement

Trade Union Recognition Agreement Company No: SC415704 Scottish Charity No: SC043442 CONTENTS 1. Purpose 2. General Principles 3. Representatives: Numbers and Constituencies 4. Appointment of Representatives 5. Definition of Representative Roles and Responsibilities 6. Review of Recognition Agreement Appendix 1: Summary of Recognised Trade Unions 1. Purpose The Trust is committed to the principle of collective bargaining and recognises the important role of Trade Unions in promoting and developing good employee relations and health and safety practices. This Agreement provides a robust partnership framework between the parties which fosters and supports the effective involvement of managers, employees, and employee representatives, in influencing decisions and in joint information sharing, learning and problem solving. In so doing, it supports The Trust’s vision of high quality services to the community as well as attempting to improve the quality of working life for employees. A list of Trade Unions recognised for collective bargaining purpose, is attached in Appendix 1. In the event of an amalgamation or other organisational changes within or between unions, the list will be amended accordingly. 2. General Principles The Trust and the recognised Trade Unions have a common objective in ensuring the long term efficiency and success of the Trust and its employees. Both parties recognise that the pursuit of this common objective under this Partnership/Agreement shall be by: • Union Co-operation: the recognised Trade Unions, within their own regulations, agree to co-operate with each other in their approach to consultation and negotiation with the Trust in terms of this Agreement. • Discussion: informal discussions between managers, employers or Trade Union Representatives in the early stages of proposals for change. -

1 Lists of Trade Unions and Employers' Associations

1 Lists of Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations Any trade union or employers’ association may apply to have its name included in the public lists maintained by the Certification Officer. This chapter sets out the background to that process. It also gives the numbers on the lists at 31 March 2017 and the changes that have occurred during the previous twelve months. The lists are set out in full in Appendix 1 (trade unions) and Appendix 2 (employers’ associations). Entry in the lists and its significance 1.1 The Certification Officer maintains a list of trade unions and a list of employers’ associations in accordance with the provisions of sections 2-4 and sections 123-125 of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 (“the 1992 Act”). 1.2 Listing is voluntary and any organisation of workers or of employers may apply to be listed. A fee is payable on application (see Appendix 10). The name of the organisation shall be entered in the relevant list if the Certification Officer is satisfied that it falls within the appropriate definition in the 1992 Act (see paragraphs 1.19 and 1.20). The Act does not impose any test of size or effectiveness but entry in the list is not automatic. The Certification Officer will test whether the organisation satisfies the statutory definition. There are simplified provisions for the listing of a trade union or unincorporated employer’s association formed by the amalgamation of two or more trade unions or unincorporated employers’ association which were already on the list (see paragraph 1.6). -

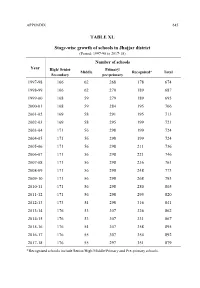

TABLE XL Stage-Wise Growth of Schools in Jhajjar District

APPENDIX 645 TABLE XL Stage-wise growth of schools in Jhajjar district (Period: 1997-98 to 2017-18) Number of schools Year High/ Senior Primary/ Middle Recognized* Total Secondary pre-primary 1997-98 166 62 268 178 674 1998-99 166 62 270 189 687 1999-00 168 59 279 189 695 2000-01 168 59 284 195 706 2001-02 169 58 291 195 713 2002-03 169 58 295 199 721 2003-04 171 56 298 199 724 2004-05 171 56 298 199 724 2005-06 171 56 298 211 736 2006-07 171 56 298 221 746 2007-08 171 56 298 236 761 2008-09 171 56 298 248 773 2009-10 171 56 298 268 793 2010-11 171 56 298 280 805 2011-12 171 56 298 295 820 2012-13 173 54 298 316 841 2013-14 176 53 307 326 862 2014-15 176 53 307 331 867 2015-16 176 54 307 358 895 2016-17 176 55 307 354 892 2017-18 176 55 297 351 879 *Recognised schools include Senior/High/Middle/Primary and Pre-primary schools. 646 JHAJJAR DISTRICT GAZETTEER TABLE XLI Students enrolled in Government High / Senior Secondary Schools of the district (Period: 2005-06 to 2017-18) Year High School Senior Secondary School 2005-06 13,898 13,559 2006-07 13,128 12,911 2007-08 11,993 11,928 2008-09 12,085 12,204 2009-10 12,311 13,760 2010-11 13,814 12,240 2011-12 12,518 11,955 2012-13 12,477 11,864 2013-14 12,627 12,881 2014-15 12,676 13,211 2015-16 12,572 9,404 2016-17 10,397 11,781 2017-18 12,826 9,832 APPENDIX 647 TABLE XLII List of Regional Centres of National Institute of Open Schooling in Jhajjar (as on 31.3.2018) 1. -

Statistics of Trade Union Membership

STATISTICS OF TRADE UNION MEMBERSHIP Data for 49 countries taken mainly from national statistical publications August 2010 ILO Bureau of Statistics (unpublished) 2. Data are currently available in Excel for the following countries: Antigua and Barbuda Australia Barbados Belgium Belize Bermuda Brazil Canada China Colombia Denmark Dominica Egypt El Salvador Finland France Germany Guatemala Guyana Hong Kong, China Iceland India Ireland Japan Korea, Republic of Kuwait Malaysia Malta Montserrat Netherlands New Zealand Norway Pakistan Philippines St Kitts and Nevis St Lucia St Vincent and the Grenadines Singapore Slovakia South Africa Sri Lanka Suriname Sweden Switzerland Syrian Arab Republic Turkey United Kingdom United States 3. METHODOLOGICAL NOTE the coverage of the union membership may be broader or narrower, depending on the inclusion of the self-employed, or retired workers, etc. or The data in these tables are the official national the unemployed, or the exclusion of certain statistics taken mainly from national groups. The rates shown are those calculated publications, but in a few cases other sources by the countries themselves, where available; have been used. This is indicated in the tables for some countries, the ILO Bureau of Statistics and in the notes that follow. The figures have has calculated the rates using as denominator not been adjusted in any way, but are as shown the total number of paid employees as in the publications. published in the ILO Yearbook of Labour Statistics (Table 2E). For a number of reasons, the data may not be directly comparable between countries. The country notes provide information, where available, about the sources of the data For some countries, the data are drawn from (including coverage and definitions), the types the official reports of trade unions submitted in of classifications used (for example, by industry, accordance with laws or regulations to the occupation, sex, region), the publications in competent authority, such as a certification which the data appear (the code in parentheses officer or registrar. -

Fight Capitalist Restoration! for Workers Political Revolution!

50C!: No. 714 ....U23 28 May 1999 AP China: Harrity/U.S. News & World Report Fight Capitalist Restoration! For Workers Political Revolution! We print below in edited form the first Beijing bureaucracy's drive toward capitatist restoration has created massive Communist protests. As you've seen on part of a presentation by Spartaeist unemployment, deepening poverty. In April U~S: visit, Chinese premier Zhu TV, there certainly have been protests League Central Committee member Ray Rongji sought entry into ·Imperialist-dominated World Trade Organization. recently-four straight days of students Bishop at an SL forum in Chicago on and working people coming out in Bei May 15. jing, throwing rocks at the U.S. embassy In the past year, just about every and shouting, "Down with U.S. imperial major newspaper has had articles about ism!" Not quite what the U.S. had bar the approach on June 4 of the tenth anni gained for. versary of the Tiananmen massacre threatened the rule of the Beijing regime. Western bourgeois propaganda has Now, we're not in a position to know, the Chinese government's bloody crack The mass outpouring of defiance her falsely portrayed these protests as out so we can't tell you if the American down on mass protests. Beginning with alded the beginnings of a proletarian bursts of anti-Communism and of fer bombing of the Chinese embass}' in Bel students but increasingly drawing in political revolution which would have vor for Western-style "democracy:' And grade, which is what these people were workers chafing under the impact of pro swept away the corrupt and despised Sta the imperialists were hoping that the demonstrating about, was a deliberate capitalist "market reforms," this upheaval linist bureaucracy in Beijing. -

Russian Trade Unions and Industrial Relations in Transition

Russian Trade Unions and Industrial Relations in Transition Sarah Ashwin and Simon Clarke Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave, 2002 Contents List of Figures and Tables ix Acronyms and abbreviations xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Trade Unions and Industrial Relations in the Soviet System 8 The formation of the soviet trade unions 8 After Lenin: the fate of the unions 14 The structure and functions of soviet trade unions 17 The regulation of the employment relationship 22 Trade unions and the labour collective under perestroika 26 The reform of the trade unions under perestroika 30 Post-soviet trade unions in search of a role 33 3 Trade Unions and Politics in Post-Soviet Russia 36 Trade unions and politics in the Yeltsin era 38 The challenge of Yeltsin’s reforms 38 FNPR in the confrontation between Yeltsin and Parliament 41 FNPR’s change of line 42 Trade unions during the first Duma (1994–6) 44 The unions in the 1995 election 47 Lobbying the second Duma (1996–9) 50 The 1999 Duma election 55 The 2000 Presidential election and FNPR under Putin 60 The campaign against the Unified Social Tax and the Labour Code 62 FNPR under threat 68 Conclusion 71 v vi Trade Unions and Industrial Relations in Russia 4 The Structure of Russian Trade Unions 73 International Relations of the Russia trade unions 75 FNPR 76 The branch unions 78 Regional trade union organisations 81 Trade union membership 86 Membership dues 88 Trade union property 90 The trade union apparatus 93 Who are the trade union officers? 95 Trade union expenditure 98 5 The Legal Framework of Industrial