Unstable Masks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Player's Guide Part 1

A Player’s Guide Effective: 9/20/2010 Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2010 Core Rulebook Part 1 – Clarifications Section 1: Rulebook 3 Section 2: Powers and Abilities 5 Section 3: Abilities 9 Section 4: Characters and Special Powers 11 Section 5: Special Characters 19 Section 6: Team Abilities 21 Section 7: Alternate Team Abilities 23 Section 8: Objects 25 Section 9: Maps 27 Part 2 – Current Wordings Section 10: Powers 29 Section 11: Abilities 33 Section 12: Characters and Special Powers 35 Section 13: Team Abilities 71 Section 14: Alternate Team Abilities 75 Section 15: Objects 77 Section 16: Maps 79 How To Use This Document This document is divided into two parts. The first part details every clarification that has been made in Heroclix for all game elements. These 40 pages are the minimal requirements for being up to date on all Heroclix rulings. Part two is a reference guide for players and judges who often need to know the latest text of any given game element. Any modification listed in part two is also listed in part one; however, in part two the modifications will be shown as fully completed elements of game text. [This page is intentionally left blank] Section 1 Rulebook at the time that the player gives the character an action or General otherwise uses the feat.‖ Characters that are removed from the battle map and placed Many figures have been published with rules detailing their on feat cards are not affected by Battlefield Conditions. -

The World's Greatest Heroes for D&D 5E

The Vengeance The World's Greatest Heroes for D&D 5E In a world filled with heroes, some still known as Captain Americana – in honour of manage to stand above their peers. The his long-lost homeland – and the Man of band known as The Vengeance are among Iron, an exceptionally talented arcanist that the most respected men and women to battles from within the confines of his have ever taken up arms in defence of enchanted Iron Plate armor. righteousness and the very survival of all The final two core members are a pair of civilised peoples. deadly assassins. Black Spider is reputed to The exact make-up of the group varies over be an exceptionally talented spy and time, but there are six heroes that are widely infiltrator, able to blend in with all manner of recognised as its core. races and deliver death with a single blow. Though primarily made up of humans, The She’s often accompanied by Eagle Eye, widely Vengeance nevertheless includes the huge, believed to be the greatest archer in rage-fuelled aberration known as the Hulking existence. One and a powerful celestial named Odinson Their methods are sometimes called into that claims to wield the power of thunder. question, but once they get to work it’s rare The more public-facing members of the that anybody is able to do anything but group include its leader, a former soldier marvel at their effectiveness. art by thedurrrrian || thedurrrrian..deviantart..com design by u/therainydaze || winghornpress..com Captain Americana Teamwork. When Captain Americana is within 5 ft. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Schurken Im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel Beschäftigt Sich Mit Den Gegenspielern Der ComicFigur „Batman“

Schurken im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel beschäftigt sich mit den Gegenspielern der Comic-Figur ¹Batmanª. Die einzelnen Figuren werden in alphabetischer Reihenfolge vorgestellt. Dieser Artikel konzentriert sich dabei auf die weniger bekannten Charaktere. Die bekannteren Batman-Antagonisten wie z.B. der Joker oder der Riddler, die als Ikonen der Popkultur Verankerung im kollektiven Gedächtnis gefunden haben, werden in jeweils eigenen Artikeln vorgestellt; in diesem Sammelartikel werden sie nur namentlich gelistet, und durch Links wird auf die jeweiligen Einzelartikel verwiesen. 1 Gegner Batmans im Laufe der Jahrzehnte Die Gesamtheit der (wiederkehrenden) Gegenspieler eines Comic-Helden wird im Fachjargon auch als sogenannte ¹Schurken-Galerieª bezeichnet. Batmans Schurkengalerie gilt gemeinhin als die bekannteste Riege von Antagonisten, die das Medium Comic dem Protagonisten einer Reihe entgegengestellt hat. Auffällig ist dabei zunächst die Vielgestaltigkeit von Batmans Gegenspielern. Unter diesen finden sich die berüchtigten ¹geisteskranken Kriminellenª einerseits, die in erster Linie mit der Figur assoziiert werden, darüber hinaus aber auch zahlreiche ¹konventionelleª Widersacher, die sehr realistisch und daher durchaus glaubhaft sind, wie etwa Straûenschläger, Jugendbanden, Drogenschieber oder Mafiosi. Abseits davon gibt es auch eine Reihe äuûerst unwahrscheinlicher Figuren, wie auûerirdische Welteroberer oder extradimensionale Zauberwesen, die mithin aber selten geworden sind. In den frühesten Batman-Geschichten der 1930er und 1940er Jahre bekam es der Held häufig mit verrückten Wissenschaftlern und Gangstern zu tun, die in ihrem Auftreten und Handeln den Flair der Mobster der Prohibitionszeit atmeten. Frühe wiederkehrende Gegenspieler waren Doctor Death, Professor Hugo Strange und der vampiristische Monk. Die Schurken der 1940er Jahre bilden den harten Kern von Batmans Schurkengalerie: die Figuren dieser Zeit waren vor allem durch die Abenteuer von Dick Tracy inspiriert, der es mit grotesk entstellten Bösewichten zu tun hatte. -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

P|Lf Llte^?*F• ^J^'F'^'»:Y^-^Vv1;' • / ' ^;

Poisonous Animals of the Desert Item Type text; Book Authors Vorhies, Charles T. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Public Domain: This material has been identified as being free of known restrictions under U.S. copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights. Download date 29/09/2021 16:26:58 Item License http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194878 University of Arizona College of Agriculture Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin No. 83 j ^.^S^^^T^^r^fKK' |p|p|lf llte^?*f• ^j^'f'^'»:Y^-^Vv1;' • / ' ^; Gila Monster. Photograph from life. About one-fifth natural size. Poisonous Animals of the Desert By Charles T. Vorhies Tucson, Arizona, December 20, 1917 UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION GOVERNING BOARD (REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY) ttx-Officio His EXCELLENCY, THE GOVERNOR OF ARIZOX v THE STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUULIC INSTRUCTION Appointed by the Governor of the State WILLI\M V. WHITMORE, A. M., M. D Chancellor RUDOLPH R VSMESSEN Treasurer WILLIAM J. BRY VN, JR., A, B Secretary vViLLi \M Sc \RLETT, A. B-, B. D Regent JOHN P. ORME Regent E. TITCOMB Regent JOHN W. FUNN Regent CAPTAIN J. P. HODGSON Regent RLIFUS B. \ON KLEINSMITI, A. M., Sc. D President of the University Agricultural Staff ROBERT H. FORBES, Ph. D. Dean and Director JOHN J. THORNBER, A. M Botanist ALBERT E. VINSON, Ph. D Biochemist CLIFFORD N. CATLJN, A, M \ssistunt Chemist GEORGE E. P. SMITH, C. E Irrigation Engineer FRANK C. KELTON, M. S \ssistnnt Engineer GEORGE F. -

The Trail to LOBO: the First Afrian-American Comic Book Hero

Details: Amazon rank: #1,870,800 Price: $25.75 bound: 132 pages Publisher: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (March 17, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 1544614721 ISBN-13: 978-1544614724 Weight: 9 ounces The Trail to LOBO: the First Afrian-American Comic Book Hero by Tony & Tony Tallarico rating: 5.0 (1 reviews) ->>->>->>DOWNLOAD BOOK The Trail to LOBO: the First Afrian-American Comic Book Hero ->>->>->>ONLINE BOOK The Trail to LOBO: the First Afrian-American Comic Book Hero 1 / 6 2 / 6 3 / 6 4 / 6 . Warner Bros. Has 11 DC Comics Movies . with additional superhero films having . DC currently has a total of eleven comic book film adaptations in .Top 5 Biggest Rip-Off Characters in Comics. They just got the comic book . If everyones going to bitch about who was first then every super hero is a .. Wonder Woman represents not just the first blockbuster helmed by a female superhero, but also the first . The comic book adaptation game is . first black .how is the first black superhero i all comic books? . How is the first black superhero i all comic . Lobo from Dell Comics is the first black .Moved Permanently. The document has moved here. Critical Mention.Watchmen is a twelve-issue comic book limited . of the Black Freighter comic . of the contemporary superhero comic book," is "a domain he .Image of the day: Old school Lobo returns . (duh, hes in every book these days), Black Canary . Fangrrls Wonder Woman Shea Fontana DC Superhero Girls DC .Characters; Comics; Movies; TV; Games; Collectibles; . the first and most influential super hero of all time has inspired us across comic books, .Vintage Lobo #1 Dell Western 1965 1st African American Comic Hero . -

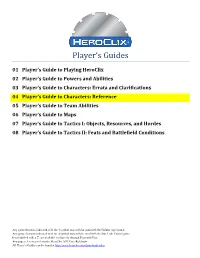

Characters – Reference Guide

Player’s Guides 01 Player’s Guide to Playing HeroClix 02 Player’s Guide to Powers and Abilities 03 Player’s Guide to Characters: Errata and Clarifications 04 Player’s Guide to Characters: Reference 05 Player’s Guide to Team Abilities 06 Player’s Guide to Maps 07 Player’s Guide to Tactics I: Objects, Resources, and Hordes 08 Player’s Guide to Tactics II: Feats and Battlefield Conditions Any game elements indicated with the † symbol may only be used with the Golden Age format. Any game elements indicated with the ‡ symbol may only be used with the Star Trek: Tactics game. Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play. Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2013 Core Rulebook. All Player’s Guides can be found at http://www.heroclix.com/downloads/rules Table of Contents Legion of Super Heroes† .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Avengers† ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Justice League† ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mutations and Monsters† ................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

BATMAN: a HERO UNMASKED Narrative Analysis of a Superhero Tale

BATMAN: A HERO UNMASKED Narrative Analysis of a Superhero Tale BY KELLY A. BERG NELLIS Dr. William Deering, Chairman Dr. Leslie Midkiff-DeBauche Dr. Mark Tolstedt A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN Stevens Point, Wisconsin August 1995 FORMC Report of Thesis Proposal Review Colleen A. Berg Nellis The Advisory Committee has reviewed the thesis proposal of the above named student. It is the committee's recommendation: X A) That the proposal be approved and that the thesis be completed as proposed, subject to the following understandings: B) That the proposal be resubmitted when the following deficiencies have been incorporated into a revision: Advisory Committee: Date: .::!°®E: \ ~jjj_s ~~~~------Advisor ~-.... ~·,i._,__,.\...,,_ .,;,,,,,/-~-v ok. ABSTRACT Comics are an integral aspect of America's development and culture. The comics have chronicled historical milestones, determined fashion and shaped the way society viewed events and issues. They also offered entertainment and escape. The comics were particularly effective in providing heroes for Americans of all ages. One of those heroes -- or more accurately, superheroes -- is the Batman. A crime-fighting, masked avenger, the Batman was one of few comic characters that survived more than a half-century of changes in the country. Unlike his counterpart and rival -- Superman -- the Batman's popularity has been attributed to his embodiment of human qualities. Thus, as a hero, the Batman says something about the culture for which he is an ideal. The character's longevity and the alterations he endured offer a glimpse into the society that invoked the transformations. -

Superheroes & Stereotypes: a Critical Analysis of Race, Gender, And

SUPERHEROES & STEREOTYPES: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF RACE, GENDER, AND SOCIAL ISSUES WITHIN COMIC BOOK MATERIAL Gabriel Arnoldo Cruz A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2018 Committee: Alberto González, Advisor Eric Worch Graduate Faculty Representative Joshua Atkinson Frederick Busselle Christina Knopf © 2018 Gabriel Arnoldo Cruz All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Alberto González, Advisor The popularity of modern comic books has fluctuated since their creation and mass production in the early 20th century, experiencing periods of growth as well as decline. While commercial success is not always consistent from one decade to the next it is clear that the medium has been and will continue to be a cultural staple in the society of the United States. I have selected this type of popular culture for analysis precisely because of the longevity of the medium and the recent commercial success of film and television adaptations of comic book material. In this project I apply a Critical lens to selected comic book materials and apply Critical theories related to race, class, and gender in order to understand how the materials function as vehicles for ideological messages. For the project I selected five Marvel comic book characters and examined materials featuring those characters in the form of comic books, film, and television adaptations. The selected characters are Steve Rogers/Captain America, Luke Cage, Miles Morales/Spider-Man, Jean Grey, and Raven Darkholme/Mystique. Methodologically I interrogated the selected texts through the application of visual and narrative rhetorical criticism. -

Suicide Squad: Vol 3 Free

FREE SUICIDE SQUAD: VOL 3 PDF John Ostrander | 280 pages | 19 Apr 2016 | DC Comics | 9781401260910 | English | United States Suicide Squad, Volume 3: Burning Down The House by Rob Williams Ask seller a question. To contact our Customer Service Team, simply click the button here and our Customer Service team will be happy to assist. Skip to main content. Email to friends Share on Facebook - opens in a new window or tab Share on Twitter - opens in a new window or tab Share on Pinterest - opens in a new window or tab. Add to Watchlist. Suicide Squad: Vol 3 listing was ended by the seller because the item is no longer available. Ships to:. This amount is subject to change until you Suicide Squad: Vol 3 payment. For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab This amount includes applicable customs duties, taxes, brokerage and other fees. For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab. Estimated Delivery within business days. Please note the delivery estimate is greater than 13 business days. Start of add to list layer. Add to Watchlist Add to wish list. Sign in for more lists. Oct 14, PDT. Seller's other items. Sell one like this. Related sponsored items Feedback on our suggestions - Related sponsored items. Rob Sikoryic The Walking Dead Compendium Volume 4. Last one. Similar sponsored items Feedback on our suggestions - Similar sponsored items. Suicide Squad 1 A - 8. Seller Suicide Squad: Vol 3 all responsibility for this listing.