Education and Skills Paper Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Locality: Life Expectancy

TRAFFORD NORTH LOCALITY HEALTH PROFILE JANUARY 2021 NORTH LOCALITY: WARDS • Clifford: Small and densely populated ward at north-east tip of the borough. Dense residential area of Victorian terraced housing and a diverse range of housing stock. Clifford has a diverse population with active community groups The area is undergoing significant transformation with the Old Trafford Master Plan. • Gorse Hill: Northern most ward with the third largest area size. Trafford town hall, coronation street studio and Manchester United stadium are located in this ward. Media city development on the Salford side has led to significant development in parts of the ward. Trafford Park and Humphrey Park railway stations serve the ward for commuting to both Manchester and Liverpool. • Longford: Longford is a densely populated urban area in north east of the Borough. It is home to the world famous Lancashire County Cricket Club. Longford Park, one of the Borough's larger parks, has been the finishing point for the annual Stretford Pageant. Longford Athletics stadium can also be found adjacent to the park. • Stretford: Densely populated ward with the M60 and Bridgewater canal running through the ward. The ward itself does not rank particularly highly in terms of deprivation but has pockets of very high deprivation. Source: Trafford Data Lab, 2020 NORTH LOCALITY: DEMOGRAPHICS • The North locality has an estimated population of 48,419 across the four wards (Clifford, Gorse Hill, Stretford & Longford) (ONS, 2019). • Data at the ward level suggests that all 4 wards in the north locality are amongst the wards with lowest percentages of 65+ years population (ONS, 2019). -

Appendix 4 Detailed Proposals for Each Ward – Organised by Local Area Partnership (LAP)

Appendix 4 Detailed proposals for each Ward – organised by Local Area Partnership (LAP) Proposed Wards within the Knutsford Local Area Partnership Knutsford Local Area Partnership (LAP) is situated towards the north-west of Cheshire East, and borders Wilmslow to the north-east, Macclesfield to the south-east and Congleton to the south. The M6 and M56 motorways pass through this LAP. Hourly train services link Knutsford, Plumley and Mobberley to Chester and Manchester, while in the east of this LAP hourly trains link Chelford with Crewe and Manchester. The town of Knutsford was the model for Elizabeth Gaskell's novel Cranford and scenes from the George C. Scott film Patton were filmed in the centre of Knutsford, in front of the old Town Hall. Barclays Bank employs thousands of people in IT and staff support functions at Radbroke Hall, just outside the town of Knutsford. Knutsford is home to numerous sporting teams such as Knutsford Hockey Club, Knutsford Cricket Club, Knutsford Rugby Club and Knutsford Football Club. Attractions include Tatton Park, home of the RHS Flower show, the stately homes Arley Hall, Tabley House and Peover Hall, and the Cuckooland Museum of cuckoo clocks. In detail, the proposals are: Knutsford is a historic, self-contained urban community with established extents and comprises the former County Ward of Knutsford, containing 7 polling districts. The Parish of Knutsford also mirrors the boundary of this proposal. Knutsford Town is surrounded by Green Belt which covers 58% of this proposed division. The proposed ward has excellent communications by road, motorway and rail and is bounded to the north by Tatton Park and to the east by Birkin Brook. -

Flltrinchflfl)

flLTRinCHflfl) Official Guide. 3-or all your requirements Ml; I»l * E RADIO AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEERS E.C.A. N.E.C.T.A. R.T.R.A. 12a OXFORD ROAD : ALTRINCHAM Tel. : ALT. 329S OP 4485. Cslimates <Tree. ALTRINCHAM OFFICIAL GUIDE Contents. Page Introduction 3, 5 and 7 Condensed Information 9 and 11 Altrincham Corporation 13,15 and 17 Altrincham Chamber of Trade 19 and 21 Postal Information 23 and 25 Education • • 27, 29 and 31 Altrincham General Hospital 33 Ringway Airport and Sport 35 Local Industry (Manufacturing) .. 35, 37 and 39 Masonic Lodges 47 Hotel Accommodation 43 Magistrates and Parliamentary Electoral Division . • 45 Banks 47 Motor Runs 49 Places of Public Worship ... 51 to 59 Associations, Societies and Clubs 61 to 67 Directory of Local Manufacturers 68 to 69 Index to Advertisers 71 to 72 1948 EDITION. Issued by the ALTRINCHAM CHAMBER of TRADE under the auspices of the ALTRINCHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL. S. Butler, Printer, 105, George Street, Altrincham. V— QUALITY THAT NEVER VARIES I A. E. PRYOR | for ; FRESH FRUIT, VEGETABLES, FISH j 252, STOCKPORT ROAD, Timperley Village. Ringway 2822. j Jft I^M ^ I» ^ 11 ^ * I ^fc «t^M^M^t I E. MILLS, ) MEN'S 8 BOYS' ( COMPLETE OUTFITTER 8 CLOTHIER j Every type of working clothing sold. Agents for "LYBRO" and "PECKSWEAR" Overalls, i Phone: Hltrincham 3576. \ 5, CROSS STREET, SLTRIMCHAM. ) i- o Introduction. During the Roman occupation, legionaries built the city- to-city communication from (Deva) Chester, to (Mancunium) Manchester known as Watling Street. Altrincham lies astride this ancient highway, four miles from the River Mersey boundary at Sale. -

NOTICE of ELECTION Trafford Council Election of District Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION Trafford Council Election of District Councillors for the Wards listed below Number of Number of District District Wards Wards Councillors to Councillors to be elected be elected Altrincham One Hale Barns One Ashton Upon Mersey One Hale Central One Bowdon Two Longford Two Broadheath One Priory Two Brooklands One Sale Moor One Bucklow-St Martins One St Mary's One Clifford One Stretford One Davyhulme East One Timperley One Davyhulme West One Urmston One Flixton Two Village One Gorse Hill One 1. Nomination papers for this election can be downloaded from the Electoral Commission website or may be obtained from the Returning Officer at Room SF.241, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH, who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Completed nomination papers must be delivered by hand to the Returning Officer, Committee Room 1 Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH, on any weekday (Monday to Friday inclusive (excluding bank and public holidays)) after the date of this notice on between 10am and 4pm but no later than 4pm on Thursday 8 April 2021. 3. If any election is contested the poll will take place on Thursday 6 May 2021. 4. Applications to register to vote at this election must reach the Electoral Registration Officer by 12 midnight on Monday 19 April 2021.Applications may be made online: www.gov.uk/register to vote or sent directly to the Electoral Registration Officer at Room SF.241, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH. -

Sunshine Tour 2021 List of Registered Venues

Sunshine Tour 2021 List of Registered Venues *To search for a venue - type 'CTRL F' and type the centre/county name or address. Show/Club/Centre County Show Address Post Code Website Clarence Esplanade, Southsea, All Stars Jumping Events Hampshire Portsmouth PO5 3PE All Stars jumping events Facebook Graceland'S Equestrian Centre, Crutch Alvechurch Riding Club Worcestershire Lane, Elmbridge, Droitwich WR9 0BR www.alvechurchridingclub.co.uk Sallow Lane, Larling Anvil Park Stud Norfolk NR16 2QU www.anvil-park-stud.co.uk APHS London Counties Horse Pachesham Equestrian Centre Show Surrey KT22 0AL www.aphs.org.uk Astley Show Field, Astley Lane, Ardsley Horse And Pony Club West Yorkshire Swillington, Leeds LS26 8HF www.ardsleyhpc.co.uk Gaston Farm, School Hill, Slindon , Arundel And District Riding Club West Sussex Arundel BN18 0RS www.arundelridingclub.com Aspley Guise And District Riding Wing Dressage & Jumping Centre, Club Bedfordshire Cublington Road, Leighton Buzzard LU7 0LB www.aspleyguiseridingclub.com Aspley Guise And District Riding Addington Equestrian Centre, Club Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire MK18 2JR www.aspleyguiseridingclub.com Barleylands Ec Barleylands Road Basildon Barleylands Arena Essex Essex SS15 4BG Www.barleylandsarena.co.uk Main Road Rettendon Common Beechwood Equestrian Centre Essex CM38DY Beechwood Equestrian Centre Fairoak Grange Equestrian Centre, Berkshire County Riding Club Berkshire Ashford Hill, Berkshire RG19 8BL www.berkscountyrc.co.uk The Polegrove, Brockley Road, Bexhill On Bexhill Horse Show East Sussex Sea -

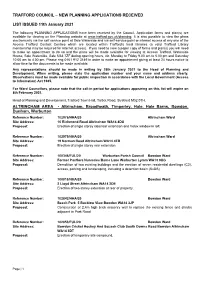

Trafford Council – New Planning Applications Received

TRAFFORD COUNCIL – NEW PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED LIST ISSUED 11th January 2021 The following PLANNING APPLICATIONS have been received by the Council. Application forms and plan(s) are available for viewing on the Planning website at www.trafford.gov.uk/planning. It is also possible to view the plans electronically via the self service point at Sale Waterside and via self-service point or internet access at any one of the Access Trafford Contact Centres which are located within Trafford’s local libraries (a valid Trafford Library membership may be required for internet access). If you need to view a paper copy of forms and plan(s) you will need to make an appointment to do so and the plans will be made available for viewing at Access Trafford, Waterside House, Sale Waterside, Sale M33 7ZF during opening hours, viz. Monday to Friday 9.00 am to 5.00 pm and Saturday 10.00 am to 4.00 pm. Please ring 0161 912 3149 in order to make an appointment giving at least 24 hours notice to allow time for the documents to be made available. Any representations should be made in writing by 28th January 2021 to the Head of Planning and Development. When writing, please state the application number and your name and address clearly. Observations must be made available for public inspection in accordance with the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985. For Ward Councillors, please note that the call-in period for applications appearing on this list will expire on 8th February 2021. Head of Planning and Development, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford M32 0TH. -

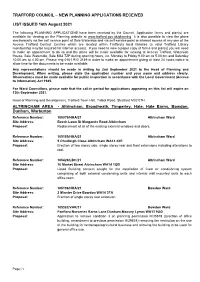

NEW PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED LIST ISSUED 16Th August 2021 ALTRINCHAM AREA

TRAFFORD COUNCIL – NEW PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED LIST ISSUED 16th August 2021 The following PLANNING APPLICATIONS have been received by the Council. Application forms and plan(s) are available for viewing on the Planning website at www.trafford.gov.uk/planning. It is also possible to view the plans electronically via the self service point at Sale Waterside and via self-service point or internet access at any one of the Access Trafford Contact Centres which are located within Trafford’s local libraries (a valid Trafford Library membership may be required for internet access). If you need to view a paper copy of forms and plan(s) you will need to make an appointment to do so and the plans will be made available for viewing at Access Trafford, Waterside House, Sale Waterside, Sale M33 7ZF during opening hours, viz. Monday to Friday 9.00 am to 5.00 pm and Saturday 10.00 am to 4.00 pm. Please ring 0161 912 3149 in order to make an appointment giving at least 24 hours notice to allow time for the documents to be made available. Any representations should be made in writing by 2nd September 2021 to the Head of Planning and Development. When writing, please state the application number and your name and address clearly. Observations must be made available for public inspection in accordance with the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985. For Ward Councillors, please note that the call-in period for applications appearing on this list will expire on 13th September 2021. Head of Planning and Development, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford M32 0TH. -

'After Housing Costs' Child Poverty Rate from Highest to Lowest

Notes: This spreadsheet ranks wards in Greater Manchester by their 'after housing costs' child poverty rate from highest to lowest. This is done using data published by End Child Poverty in 2019. The data also ranks areas based on the proportion of the population in a ward classified as black and minority ethnic (BAME) in census data. The higher the proportion of people who are BAME in a ward the higher the rank. This data shows that areas with the highest BAME populations in Greater Manchester are often the areas with the highest rates of child poverty. Local Ward GM Child poverty rank GM BAME authority area (after housing costs) rank Oldham Werneth 1 1 Oldham St Mary's 2 6 Oldham Coldhurst 3 3 Manchester Longsight 4 4 Salford Ordsall 5 48 Manchester Cheetham 6 9 Rochdale Central Rochdale 7 10 Manchester Hulme 8 16 Rochdale Milkstone and Deeplish 9 2 Manchester Gorton South 10 17 Rochdale Kingsway 11 23 Salford Broughton 12 47 Bolton Great Lever 13 13 Manchester Rusholme 14 11 Salford Kersal 15 82 Oldham Alexandra 16 25 Oldham Medlock Vale 17 22 Salford Irwell Riverside 18 55 Manchester Crumpsall 19 15 Manchester Ardwick 20 12 Manchester Bradford 21 29 Manchester Miles Platting and Newton Heath 22 52 Tameside St Peter's 23 30 Bolton Rumworth 24 7 Salford Langworthy 25 72 Manchester Gorton North 26 27 Bury Sedgley 27 56 Bolton Harper Green 28 37 Bolton Halliwell 29 20 Manchester Ancoats and Clayton 30 40 Rochdale Smallbridge and Firgrove 31 36 Manchester Levenshulme 32 18 Trafford Clifford 33 8 Manchester Moss Side 34 5 Manchester Fallowfield -

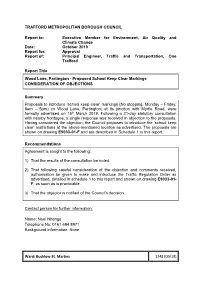

Wood Lane Partington Skc Obj PDF 404 KB

TRAFFORD METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL Report to: Executive Member for Environment, Air Quality and Climate Change Date: October 2019 Report for: Approval Report of: Principal Engineer, Traffic and Transportation, One Trafford Report Title 1 Wood Lane, Partington - Proposed School Keep Clear Markings CONSIDERATION OF OBJECTIONS 1 Summary A Proposals to introduce ‘school keep clear’ markings (No stopping, Monday – Friday, 8am – 5pm) on Wood Lane, Partington; at its junction with Myrtle Road, were formally advertised on 15th March 2019. Following a 21-day statutory consultation with nearby frontages, a single response was received in objection to the proposals. Having considered the objection, the Council proposes to introduce the ‘school keep clear’ restrictions at the above-mentioned location as advertised. The proposals are shown on drawing E9033-01-F and are described in Schedule 1 to this report. A Recommendations A Agreement is sought to the following: 1) That the results of the consultation be noted. 2) That following careful consideration of the objection and comments received, authorisation be given to make and introduce the Traffic Regulation Order as advertised, detailed in schedule 1 to this report and shown on drawing E9033-01- F, as soon as is practicable. 3) That the objector is notified of the Council’s decision. Aa Contact person for further information: Name: Noel Nhengu Telephone No: 0161 694 8971 Background information: None a a Ward: Bucklow-St. Martins 1348 (09/19) a a 1.0 BACKGROUND 1.1 Forest Gate Academy is a Primary School in Partington with a pedestrian entrance which can be accessed via Myrtle Road and Wood Lane. -

West Locality Health Profile

TRAFFORD WEST LOCALITY HEALTH PROFILE JANUARY 2021 WEST LOCALITY: WARDS • Bucklow-St Martins: Second largest ward in the Borough. It is characterised by large areas of agricultural green belt land including Carrington Moss. Within the ward are a large industrial complex and Carrington Business Park. Within the south east part of the ward are the villages of Carrington and Partington and within the eastern area is the residential area of Sale. The northern boundary of the site is bounded by the River Mersey. The ward is home to the Manchester United and Manchester City Football Clubs training grounds. Bucklow - St Martins has three very distinct areas with pockets of high deprivation and isolated communities. • Davyhulme East: In the north of Trafford and is bounded to the north by the Manchester Ship Canal and the Bridgewater Canal. The ward is home to the Trafford Centre, separated from the residential areas by the M60, the historical Barton Aqueduct, which crosses the Manchester Ship Canal and Barton Swing Bridge. • Davyhulme West: Bounded by the Manchester Ship Canal to the west, Davyhulme waste water treatment works to the north and residential areas of Davyhulme and Flixton to the east and south. The ward is mainly residential with large areas of private open land along the canal edge and the Mersey Valley to the south east tip of the ward. Trafford General Hospital is located in this ward. • Flixton: Bounded by the Mersey Valley and the River Mersey to the south and is traversed by the Manchester to Liverpool railway line. Its population is concentrated in areas in the northern half of the ward; other areas are generally open and include two golf courses (William Wroe and Flixton Golf Course). -

Performance Report

Chair’s report – 1st June to 31st August 2018 ............................................... 2 Health Scrutiny Committee ............................................................. 2 Mental Health in Trafford ............................................................... 2 New board members ..................................................................... 3 Ageing Well ................................................................................ 3 Intermediate care ........................................................................ 3 Greater Manchester Healthwatch ...................................................... 3 Personal Independence Payments (PIP) ............................................... 3 NHS at 70 .................................................................................. 3 Volunteers ................................................................................. 4 Mental Health in Greater Manchester ................................................. 4 Advisory Group ............................................................................ 5 Phlebotomy ................................................................................ 5 Annual report ............................................................................. 6 Appendix 1 - Public engagement ............................................................ 8 Online and social media statistics June - July 2018 ................................... 9 Appendix 2 – Feedback analysis ........................................................... -

The Swan, Mereside Road, Bucklow Hill, Knutsford WA16

The Swan, Mereside Road, Bucklow Hill, Knutsford WA16 6RD Freehold hotel, restaurant and public house with potential for a number of alternative uses including residential, care or retirement living The Swan Mereside Road, Bucklow Hill, Knutsford WA16 6RD Summary Location • Located 3.5 miles north west of Knutsford, The site is located in the village of Bucklow Hill, five miles west of Manchester Airport and approximately 15 miles south west of Manchester, 15 miles south west of Central Manchester 3.5 miles north west of Knutsford and 5.8 miles south west of Altrincham. • 68 bedroom hotel and restaurant with potential for alternative uses including residential, care or Bucklow Hill is a small residential settlement which has retirement living been enhanced in recent years by the downgrading of • Existing GIA c.38,858 sq ft (3,610 sq m) Chester Road into a single carriageway, reducing the traffic flow through the village. The site is situated to the • Accessed via the junction of Mereside Road east side of Chester Road at the junction of Mereside and Chester Road, 6.8 miles (11km) south of Road and Cicely Mill Lane. the A556 • Total site area extends to c.3.2 acres (1.29 ha) Knutsford and the surrounding area is a sought-after residential location within easy commuting distance • Further information including architectural of both Liverpool and Manchester. There is an array feasibility study available of local amenities in Knutsford, with a large selection • Offers sought for the freehold interest on an of restaurants, bars and shops. Knutsford also hosts unconditional or conditional (subject to many events throughout the year, including The RHS planning) basis Flower show at Tatton Park, to the north of the town containing the medieval manor house Tatton Hall.