Foraging Flight Distances of Wintering Ducks and Geese: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Shoveler Anas Clypeata

Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata Folk Name: Spoonbill, Broad-bill, Spoon Bill Teal Status: Migrant, Winter Resident/Visitor Abundance: Uncommon Habitat: Lakes, ponds Take one good look at a Northern Shoveler and you will quickly realize how it acquired its various common names. Its large, conspicuous, spoon-shaped bill is unlike the bill of any other duck in the Carolinas. When viewed from above, the bill appears a bit like a shoe horn, narrow at the base and flaring out widely towards its rounded end, which can be a tad wider than the duck’s head. The shoveler is a heavy-bodied dabbling duck related to our teal ducks, but at 19 inches long, it is 3 ½ inches bigger reported one at Cowan’s Ford Wildlife Refuge on the than the Blue-winged and 5 inches bigger than the Green- very early date of 7 August in 1988, and one was reported winged Teal. Like our other dabbling ducks, it prefers lingering in Charlotte on April 28, 2012. Usually fewer shallow waters for foraging but any size pond will do. than 10 birds are seen at a time; however, an impressive In 1909, T. G. Pearson shared this assessment of the total of 948 was counted at Pee Dee NWR on January 2, Northern Shoveler with readers of the Greensboro Daily 2010. Historically, this duck was more common in the News: region during migration, but many mid-winter reports have been received since the turn of the twenty-first The male shoveler is a striking bird and the green century. of his head often leads the hasty observer at a Mary Akers, a 12-year-old bird watcher in Charlotte, distance to believe that he is looking at a mallard, shared this story of a weekend encounter with a “Spoon the similarity also being heightened in part by the Bill Teal,” in 1940: large size of the bird. -

Waterfowl in Iowa, Overview

STATE OF IOWA 1977 WATERFOWL IN IOWA By JACK W MUSGROVE Director DIVISION OF MUSEUM AND ARCHIVES STATE HISTORICAL DEPARTMENT and MARY R MUSGROVE Illustrated by MAYNARD F REECE Printed for STATE CONSERVATION COMMISSION DES MOINES, IOWA Copyright 1943 Copyright 1947 Copyright 1953 Copyright 1961 Copyright 1977 Published by the STATE OF IOWA Des Moines Fifth Edition FOREWORD Since the origin of man the migratory flight of waterfowl has fired his imagination. Undoubtedly the hungry caveman, as he watched wave after wave of ducks and geese pass overhead, felt a thrill, and his dull brain questioned, “Whither and why?” The same age - old attraction each spring and fall turns thousands of faces skyward when flocks of Canada geese fly over. In historic times Iowa was the nesting ground of countless flocks of ducks, geese, and swans. Much of the marshland that was their home has been tiled and has disappeared under the corn planter. However, this state is still the summer home of many species, and restoration of various areas is annually increasing the number. Iowa is more important as a cafeteria for the ducks on their semiannual flights than as a nesting ground, and multitudes of them stop in this state to feed and grow fat on waste grain. The interest in waterfowl may be observed each spring during the blue and snow goose flight along the Missouri River, where thousands of spectators gather to watch the flight. There are many bird study clubs in the state with large memberships, as well as hundreds of unaffiliated ornithologists who spend much of their leisure time observing birds. -

13.3.3. Aquatic Invertebrates Important for Waterfowl Production

WATERFOWL MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK 13.3.3. Aquatic Invertebrates Important for Waterfowl Production Jan Eldridge that wetland. For example, invertebrates such as Bell Museum of Natural History leeches, earthworms, zooplankton, amphipods, University of Minnesota isopods, and gastropods are dependent on passive Minneapolis, MN 55455 dispersal (they can’t leave the wetland under their own power). As a result, they have elaborate mecha- Aquatic invertebrates play a critical role in the nisms to deal with drought and freezing. A second diet of female ducks during the breeding season. group that includes some beetles and most midges Most waterfowl hens shift from a winter diet of can withstand drought and freezing but requires seeds and plant material to a spring diet of mainly water to lay eggs in spring. A third group that in- invertebrates. The purpose of this chapter is to give cludes dragonflies, mosquitoes, and phantom managers a quick reference to the important inver- midges lays eggs in the moist mud of drying wet- tebrate groups that prairie-nesting ducks consume. lands during summer. A fourth group that includes Waterfowl species depend differentially on the most aquatic bugs and some beetles cannot cope various groups of invertebrates present in prairie with drying and freezing, so,they leave shallow wet- wetlands, but a few generalizations are possible. lands to overwinter in larger bodies of water. Man- agers can use the presence of these invertebrates to Snails, crustaceans, and insects are important inver- determine the effectiveness of water management tebrate groups for reproducing ducks (Table). Most regimes designed for waterfowl production. species of laying hens rely on calcium from snail The following descriptions of invertebrate natu- shells for egg production. -

CP Bird Collection

Lab Practical 1: Anseriformes - Caprimulgiformes # = Male and Female * = Specimen out only once Phalacrocoracidae Laridae Anseriformes Brandt's Cormorant * Black Skimmer Anatidae American Wigeon Double-crested Cormorant Bonaparte's Gull California Gull Bufflehead Ciconiiformes Forster's Tern Canvasback Ardeidae Heermann's Gull Cinnamon Teal Black-crowned Night-Heron Ring-billed Gull Common Goldeneye Cattle Egret Royal Tern Fulvous Whistling-Duck Great Blue Heron Gadwall Great Egret Western Gull Green-winged Teal Green Heron Alcidae Common Murre Lesser Scaup Least Bittern Mallard Snowy Egret Columbiformes Columbidae Northern Pintail Falconiformes Band-tailed Pigeon Northern Shoveler Accipitridae Mourning Dove Redhead Cooper's Hawk Rock Pigeon # Ruddy Duck * Golden Eagle Snow Goose Red-shouldered Hawk Cuculiformes # Surf Scoter Red-tailed Hawk Cuculidae Greater Roadrunner Galliformes Sharp-shinned Hawk Phasianidae White-tailed Kite Strigiformes # Ring-necked Pheasant Cathartidae Tytonidae Odontophoridae Turkey Vulture Barn Owl California Quail Falconidae Strigidae Gambel's Quail # American Kestrel Burrowing Owl Mountain Quail Prairie Falcon Great Horned Owl Western Screech-Owl Gaviiformes Gruiformes Gaviidae Rallidae Caprimulgiformes Common Loon American Coot Caprimulgidae Clapper Rail Common Nighthawk Podicipediformes Common Gallinule Podicipedidae Common Poorwill Virginia Rail Clark's Grebe Eared Grebe Charadriiformes Pied-billed Grebe Charadriidae Western Grebe Black-bellied Plover Killdeer Procellariiformes Recurvirostridae Procellariidae American Avocet Northern Fulmar Black-necked Stilt Pelecaniformes Scolopacidae Pelecanidae Greater Yellowlegs * American White Pelican Long-billed Dowitcher * Brown Pelican Marbled Godwit Western Sandpiper ZOO 329L Ornithology Lab – Topography – Lab Practical 1 BILL (BEAK) Culmen the ridge on top of the upper mandible. It extends from the tip of the bill to where the feathers begin. Gonys ridge of the lower mandible, analogous to the culmen on the upper mandible. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

2020 North Carolina Ornithology List

2020 North Carolina Ornithology List Kingdom – ANIMALIA Phylum – CHORDATA Key: Sub Phylum – VERTEBRATA Regional level (62 in total) Class – AVES Addition for State level (110 in total) Family Grou p (Family Name) Addition for National level (160 in total) Common Name [Scientific name is in italics] ORDER: Anseriformes Ibises and Spoonbills ORDER: Charadriiformes Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) (Threskiornithidae) Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Northern Shoveler Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja American Golden-Plover Green-winged Teal Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Canvasback ORDER: Suliformes Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Hooded Merganser Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) American Oystercatcher Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Double-crested Cormorant Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) Snow Goose Chen caerulescens Phalacrocorax auritus Black-necked Stilt Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) American Avocet Recurvirostra Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga americana Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnificent Frigatebird (Scolopacidae) Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera American Woodcock Scolopax minor ORDER: Ciconiiformes Spotted Sandpiper ORDER: Galliformes Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Ruddy Turnstone Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and Old Wood stork Dunlin Calidris alpina World Quail Wilson’s Snipe (Phasianidae ) ORDER: Falconiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers Ring-necked Pheasant Caracaras and Falcons (Falconidae) (Laridae) Ruffed Grouse -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Central Flyway HPAI H5N1 Surveillance Project Overview

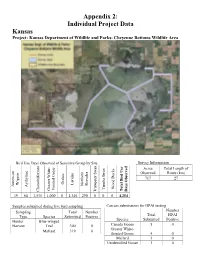

Appendix 2: Individual Project Data Kansas Project: Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks- Cheyenne Bottoms Wildlife Area Bird Use Days Observed of Sensitive Group by Site Survey Information Acres Total Length of Observed Route (km) 717 27 Grebes Laridae Wigeon Shoveler Northern American Aythyinae Wood Ducks Tundra Swan Fronted Geese Greater White- Total Bird Use Days Observed Charadriiformes Charadriiformes Trumpeter Swan Trumpeter Swan 19 64 1,535 1,000 0 1,346 290 0 0 0 4,254 Samples submitted during live bird sampling Carcass submissions for HPAI testing Sampling Total Number Number Type Species Submitted Positive Total HPAI Species Submitted Positive Hunter Blue-winged Harvest Teal 300 0 Canada Goose 5 0 Greater White- Mallard 319 0 fronted Goose 4 0 Mallard 1 0 Unidentified Goose 1 0 Project: Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks- Kirwin National Wildlife Refuge Bird Use Days Observed of Sensitive Group by Site Grebes Laridae Wigeon Shoveler Northern American Aythyinae Wood Ducks Tundra Swan Fronted Geese Greater White- Total Bird Use Days Observed Charadriiformes Charadriiformes Trumpeter Swan Trumpeter Swan 397 2,995 9 11,866 14 1,019 221 0 0 41 16,562 Carcass submissions for HPAI testing Total Number Species Submitted HPAI Positive na 0 0 Survey Information Number of Acres Observed Survey Units 1,503 29 Project: Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks- Flint Hills National Wildlife Refuge Bird Use Days Observed of Sensitive Group by Site Grebes Laridae Wigeon Shoveler Northern American Aythyinae Wood Ducks Tundra Swan Fronted -

R,S,C,O,F) Snow Goose 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Wind: C Ross' Goose 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 (N,S,E,W,C) Other 0 1 1A 2 2A B1-6 B7-14 B15-20 HC1-3 TOT Other 0

WATERFOWL SPECIES COMPOSITION REPORT AREA : KERN NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE YEAR 2014-2015 Date: January 3, 2015 1 1A 2 2A B1-6 B7-14 B15-20 HC1-3 TOT Capacity: 57 Canada Goose 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Weather: C Greater White Fronted 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 (R,S,C,O,F) Snow Goose 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Wind: C Ross' Goose 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 (N,S,E,W,C) Other 0 1 1A 2 2A B1-6 B7-14 B15-20 HC1-3 TOT Other 0 Mallard 0 3 0 0 0 1 0 0 4 Total Geese 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Gadwall 0 1 18 0 0 1 0 0 20 American Coot 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 American Widgeon 0 6 4 0 0 0 0 0 10 Common Moorhen 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Northern Pintail 0 6 2 0 0 1 0 2 11 TOTAL WATERFOWL 0 53 122 0 0 27 0 9 211 Green-winged Teal 0 22 50 0 0 10 0 4 86 Cinnamon Teal 0 5 3 0 0 1 0 0 9 Upland Birds Blue-winged Teal 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Ring-necked Pheasant 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Northern Shoveler 0 10 32 0 0 12 0 3 57 Redhead 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Canvasback 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Ring-necked Duck 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Adult WF Hunters 0 12 34 0 0 9 0 6 61 Lesser Scaup 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Jr. -

Spain - Realm of the Iberian Lynx

Spain - Realm of the Iberian Lynx Naturetrek Tour Report 29 October - 3 November 2018 Report compiled by Byron Palacios Images courtesy of Peter Heywood Naturetrek Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Spain - Realm of the Iberian Lynx Tour Participants: Byron Palacios and Niki Williamson with 12 Naturetrek clients. Day 1 Monday 29th October Gatwick – Seville – Doñana National Park It was a long day for many of us who left London Gatwick early in the morning in order to catch our flight which landed on time in Seville where we reassembled in the Arrivals area. After having a snack whilst we sorted out our vans, we were ready to set off leaving the Seville airport area and heading west towards Huelva, diverting into the north-eastern entrance of Doñana National Park at Dehesa de Abajo. The afternoon weather was glorious, with very pleasant temperature and sunshine, perfect for a birding stop at this picturesque place surrounded by water and rice fields. We had great views of Glossy Ibis, Grey Herons, White Storks, Common Pochard, Northern Shoveler, Black Stork, Western Marsh Harrier, hundreds of Greater Flamingos and Northern Lapwings, amongst others. We continued our drive towards El Rocío where we checked into our comfortable hotel and, after a very short break, we gathered together again to do our log of the day followed by dinner. Day 2 Tuesday 30th October Doñana National Park (Raya Real – FAO Visitors Centre) We gathered for breakfast at the hotel’s cafeteria on a very windy and rainy morning; but we decided to go out on our first expedition within the core area of the national park. -

Northern Shoveler Anas Clypeata the Northern Shoveler Is Primarily a Winter Visi- Tor to San Diego County, Abundant in Shallow Water Over a Muddy Bottom

Waterfowl — Family Anatidae 65 Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata The Northern Shoveler is primarily a winter visi- tor to San Diego County, abundant in shallow water over a muddy bottom. Here the shovelers can use their spatulate bills to filter the water for seeds, snails, and plankton. Small numbers remain through the summer, but the shoveler is known to have nested in San Diego County only once. Winter: The Northern Shoveler winters widely in San Diego County’s coastal wetlands and on its inland lakes. Certain lakes and lagoons, however, are sites of consis- tently large concentrations. The most important of these are O’Neill Lake (E6; up to 1000, as on 4 December 2000, Photo by Anthony Mercieca P. A. Ginsburg), Windmill Lake (G6; up to 763 on 27 December 1997, P. Unitt), Whelan Lake (G6; up to 593 on 21 January 1998, D. Rorick), Lake Hodges (K10/K11; and Sweetwater Reservoir (S12/S13; up to 800 on 14 up to 655 on 22 December 2000, R. L. Barber), San Elijo January 1999, P. Famolaro). Lagoon (L7; up to 2000 on 20 January 1998, A. Mauro), Though most common on fresh or brackish water, the shoveler also uses tidal mud- flats and salt marshes, with up to 330 in south San Diego Bay (U10) 16 December 2000 (G. Moreland). If water is adequate, shovelers exploit seasonal wet- lands and intermittently filled lakes such as Big Laguna (O23; 30 on 23 February 2002, K. J. Winter), Corte Madera (Q20/ R20; 75 on 20 February 1999, G. L. Rogers), and the upper basin of Lake Morena (S21; 550 on 16 February 1998, S. -

A Flyway Perspective of Foraging Activity in Eurasian Green-Winged Teal, Anas Crecca Crecca

81 A flyway perspective of foraging activity in Eurasian Green-winged Teal, Anas crecca crecca C. Arzel, J. Elmberg, and M. Guillemain Abstract: Time–activity budgets in the family Anatidae are available for the wintering and breeding periods. We present the first flyway-level study of foraging time in a long-distance migrant, the Eurasian Green-winged Teal, Anas crecca crecca L., 1758 (‘‘Teal’’). Behavioral data from early and late spring staging, breeding, and molting sites were collected with standardized protocols to explore differences between the sexes, seasons, and diel patterns. Teal foraging activity was compared with that of the Mallard, Anas platyrhynchos L., 1758 and Northern Shoveler, Anas clypeata L., 1758, and the potential effects of duck density and predator-caused disturbance were explored. In early spring, foraging time was moder- ate (50.5%) and mostly nocturnal (45%). It increased dramatically in all three species at migration stopovers and during molt, mostly because of increased diurnal foraging, while nocturnal foraging remained fairly constant along the flyway. These patterns adhere to the ‘‘income breeding’’ strategy expected for this species. No differences between the sexes were recorded in either species studied. Teal foraging time was positively correlated with density of Teal and all ducks present, but negatively correlated with predator disturbance. Our study suggests that Teal, in addition to being income breeders, may also be considered as income migrants; they find the energy necessary to migrate at staging sites along the flyway. Re´sume´ : Les budgets–temps des Anatidae sont disponibles pour les pe´riodes d’hivernage et de reproduction. Nous pre´- sentons la premie`re e´tude, a` l’e´chelle d’une voie de migration, du temps d’approvisionnement d’un migrateur de longue distance, la sarcelle d’hiver, Anas crecca crecca L., 1758.