Gandhi's Vision for Indian Society: Theory and Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Page Abdul Gaffar Nagar 237 Aga Khan Palace 276 Ahmed, Moulvi

INDEX A B—contd. Page Page Abdul Gaffar Nagar 237 Bombay Swarajya Party 168 Aga Khan Palace 276 Bose, Sarat Chandra 29 3 Ahmed, Moulvi Raffiuddin 80 Bose, Subhash Chandra 290 Aiyar, C. P. Ramswami 15 Brelvi, S. A 278 Akhil Bharatiya Goraksha Mandal 181 Akut, V.S. 147 C Ali Mahomed 129 Ali Sayad Reza 173 Central Khilafat Committee 95, 138, 145, All India Congress Committee 13, 14, 168, 185 26, 82, 92, 167, 168, Chagla, M. C. 1 83 193, 273, 293. Chandavarkar, Narayan, Sir 12 All India Gou Seva Sangh 274, 301 Chaturvedi, Madan Mohan 244 All India Harijan Sewak Sangh 256 Chintamani, C. Y. 163 All India Hindustani Talimi 292 Cholkar, Moreshwar Ramcha- 259 Sangh. ndra, Dr. All India Home Rule League 16, 17, 81, Chhotani, Jan Mohmed 80 82 Chowdhary, Rambhuj Dutt 80 All India Khilafat Conference 86 Chunilal Dwarkadas 293 All India Muslim League 15,173 Cutchi Jain Association 63 All India Spinners' Association 275, 296 D All India Tilak Memorial 82 Altekar, M. D. 183 Damle, S. K. 161, 186 Andrews, C. F. 39, 80 Dastagir, Vastad Ghulam 159 Aney, M. S. 240 Dastane, W. V. 154,187 Ansari, M. A. 231 Dave, M. Rohit 286 Apte, L. J. 131 Deo, S. D. 161, 187, 293 Asar, Laxmi Purshottam 265 Deogirikar, T. R. 277 Asavle, R. S. 163 Desai, Bhulabhai J. 228 Avte, T. H. 161 Desai, Madhavbhai Haribhai 96, 187 Azad, Maulana Abul Kalam 106, 228, Deshmukh, Moreshwar Gopal. Dr. 3 266 Deshpande, G. B. 69, 89,172 Deshpande, S. V. 211 B Devdhar, G K. -

N.G.M. College (Autonomous) Pollachi- 642 001

SHANLAX INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS, SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES (A Peer-Reviewed, Refereed/Scholarly Quarterly Journal with Impact Factor) Vol.5 Special Issue 2 March, 2018 Impact Factor: 2.114 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 International Conference on Contributions and Impacts of Intellectuals, Ideologists and Reformists towards Socio – Political Transformation in 20th Century Organised by DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY (HISTORIA-17) Diamond Jubilee Year September 2017 Dr.R.Muthukumaran Head, Department of History Dr.K.Mangayarkarasi Mr.R.Somasundaram Mr.G.Ramanathan Ms.C.Suma N.G.M. College (Autonomous) Pollachi- 642 001 Dr.B.K.Krishnaraj Vanavarayar President NGM College The Department of History reaches yet another land mark in the history of NGM College by organizing International Conference on “Contributions and Impacts of Intellectuals, Ideologists and Reformists towards Socio-political Transformation in 20th century”. The objective of this conference is to give a glimpse of socio-political reformers who fought against social stagnation without spreading hatred. Their models have repeatedly succeeded and they have been able to create a perceptible change in the mindset of the people who were wedded to casteism. History is a great treat into the past. It let us live in an era where we are at present. It helps us to relate to people who influenced the shape of the present day. It enables us to understand how the world worked then and how it works now. It provides us with the frame work of knowledge that we need to build our entire lives. We can learn how things have changed ever since and they are the personalities that helped to change the scenario. -

1. RAJKOT the Struggle in Rajkot Has a Personal Touch About It for Me

1. RAJKOT The struggle in Rajkot has a personal touch about it for me. It was the place where I received all my education up to the matricul- ation examination and where my father was Dewan for many years. My wife feels so much about the sufferings of the people that though she is as old as I am and much less able than myself to brave such hardships as may be attendant upon jail life, she feels she must go to Rajkot. And before this is in print she might have gone there.1 But I want to take a detached view of the struggle. Sardar’s statement 2, reproduced elsewhere, is a legal document in the sense that it has not a superfluous word in it and contains nothing that cannot be supported by unimpeachable evidence most of which is based on written records which are attached to it as appendices. It furnishes evidence of a cold-blooded breach of a solemn covenant entered into between the Rajkot Ruler and his people.3 And the breach has been committed at the instance and bidding of the British Resident 4 who is directly linked with the Viceroy. To the covenant a British Dewan5 was party. His boast was that he represented British authority. He had expected to rule the Ruler. He was therefore no fool to fall into the Sardar’s trap. Therefore, the covenant was not an extortion from an imbecile ruler. The British Resident detested the Congress and the Sardar for the crime of saving the Thakore Saheb from bankruptcy and, probably, loss of his gadi. -

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Lesson Plan Title of Lesson

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Lesson Plan Title of Lesson: Ahimsa in the Real World: Truth, Love, and Nonviolence. Lesson By: Melissa Ardon Grade Level/ Subject Areas: Class Size: Time/ Duration of Lesson: Second Grade 20 3 days 45 minutes each day Objectives of Lesson: • Students will learn to define ahimsa as love, truth, and nonviolence. • Students will create an abstract painting to show their understanding of feelings of nonviolence by using “feeling colors.” • Students will write and describe their painting and how it represents nonviolence. Lesson Abstract: Students in second grade will learn about Gandhi’s philosophy of ahimsa. Through a digital story, honesty story, abstract art, and writing, students will learn about Gandhi’s philosophy of ahimsa. Lesson Content: Background on Mohandas K. Gandhi Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in a small town of India, Porbandar. He was born to Karamchand and Putlibai Gandhi. His father served as prime minister of their town and his mother, Putlibai, was a devout illiterate hindu girl. Putlibai attended daily temple services and fasted frequently throughout the year. At the tender age of thirteen he married Kasturbai. By eighteen they were parents to a boy. They had four children. At nineteen Gandhi sailed to London to attend law school. Upon earning his law degree, he returned to India only to find no job opportunities and feeling like a failure. He was offered an attorney position in South Africa and it is where he first began to practice law. When Gandhi arrived to South Africa he had two very shocking incidents that changed his perspective. -

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 1 Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 2 BLANK z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 3 Governing Class and the Servile Class Nobody will have any quarrel with the abstract principle that nothing should be done whereby the best shall be superseded by one who is only better and the better by one who is merely good and the good by one who is bad……. But Man is not a mere machine. He is a human being with feelings of sympathy for some and antipathy for others. This is even true of the ‘best’ man. He too is charged with the feelings of class sympathies and class antipathies. Having regard to these considerations the ‘best’ man from the governing class may well turn out to be the worst from the point of view of the servile classes. The difference between the governing classes and the servile classes in the matter of their attitudes towards each other is the same as the attitude a person of one nation has for that of another nation. - Dr. Ambedkar in ‘What Congress.... etc.’ z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 4 z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 5 DR. -

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume 98

1. GIVE AND TAKE1 A Sindhi sufferer writes: At this critical time when thousands of our countrymen are leaving their ancestral homes and are pouring in from Sind, the Punjab and the N. W. F. P., I find that there is, in some sections of the Hindus, a provincial spirit. Those who are coming here suffered terribly and deserve all the warmth that the Hindus of the Indian Union can reasonably give. You have rightly called them dukhi,2 though they are commonly called sharanarthis. The problem is so great that no government can cope with it unless the people back the efforts with all their might. I am sorry to confess that some of the landlords have increased the rents of houses enormously and some are demanding pagri. May I request you to raise your voice against the provincial spirit and the pagri system specially at this time of terrible suffering? Though I sympathize with the writer, I cannot endorse his analysis. Nevertheless I am able to testify that there are rapacious landlords who are not ashamed to fatten themselves at the expense of the sufferers. But I know personally that there are others who, though they may not be able or willing to go as far as the writer or I may wish, do put themselves to inconvenience in order to lessen the suffering of the victims. The best way to lighten the burden is for the sufferers to learn how to profit by this unexpected blow. They should learn the art of humility which demands a rigorous self-searching rather than a search of others and consequent criticism, often harsh, oftener undeserved and only sometimes deserved. -

Volume Ninety-Seven : (Sep 27, 1947

1. HINDUSTANI 1 Shri Kakasaheb Kalelkar writes: If the Muslims of the Indian Union affirm their loyalty to the Union, will they accept Hindustani as the national language and learn the Urdu and Nagari scripts? Unless you give your clear opinion on this, the work of the Hindustani Prachar Sabha will become very difficult. Cannot Maulana Azad give his clear opinion on the subject? Kakasaheb says nothing new in his letter. But the subject has acquired added importance at the present juncture. If the Muslims in India owe loyalty to India and have chosen to make it their home of their own free will, it is their duty to learn the two scripts. It is said that the Hindus have no place in Pakistan. So they migrate to the Indian Union. In the event of a war between the Union and Pakistan, the Muslims of the Indian Union should be prepared to fight against Pakistan. It is true that there should be no war between the two dominions. They have to live as friends or die as such. The two will have to work in close co-operation. In spite of being independent of each other, they will have many things in common. If they are enemies, they can have nothing in common. If there is genuine friendship, the people of both the States can be loyal to both. They are both members of the same Commonwealth of nations. How can they become enemies of each other? But that discussion is unnecessary here. The Union must have a common inter provincial speech. -

Comparative Study B.R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi

Historical Research Letter www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3178 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0964 (Online) Vol.23, 2015 Comparative Study B.R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi M.SAMPATHKUMAR, PhD, Research Scholar, P.G.Research Department of History Arignar Anna Government Arts College, Musiri-621 211. Introdution Mahatma Gandhi, and Dr. B.R.Ambedkar, the chief architect of the India shared many things in common. There existed sharp contradiction also in their approaches to social reforms and in details relating to political freedom. The scheme in Gandhi was very comprehensive; it never allowed social reform to remain aside of political freedom. Gandhi bumming foreign clothes and B.R.Ambedkar buming Manusmrithi were no mere acts of sentiments; for both foreign clothes and Manusmrithi had the effect of bondage and slavery for the countrymen. A Pinch of salt from God's ocean was a political catharsis and 'a drop handful of water from the Mahad tank' was the proclamation of social philosophy. These were no symbolic gestures; they were the outward manifestations or portents of the new emerging social and political patterns, for India, in the offing. Gandhi made it clear as, "The cities live upon the villages, India is daily growing poorer. In losing the spinning wheel we lost our left lung. We are, therefore, suffering from galloping consumption it is a sin to be foreign cloth in burning foreign cloth I burn my shame". Gandhi and perspectives Gandhi held that if the country remains dependent on the master for its material necessaries, education and social harmony it could never be independent. -

1. Letter to Amrit Kaur 2. Letter to Sushila Nayyar

1. LETTER TO AMRIT KAUR LIKANDA February 23, 1940 MY DEAR IDIOT, Though we have hostile slogans1, on the whole, things have gone smooth.One never knows when they may grow worse. The atmosphere is undoubtedly bad. The weather is superb. I am keeping excellent and have regular hours. The b.p. is under control. Radical changeshave been made in the workingand composition of the Sangh.2 This you will have already seen. We are leaving here on Sunday and leaving Calcutta on Tuesday for Patna3. No more today. Mountain of work awaiting me. Your reports about the family there are encouraging. Poonam Chand Ranka4 told me he was going to correspond directly with Balkrishna about Chindwara. Evidently he has done nothing. This is unfortunate. Love to all. BAPU From the original : C.W. 3962. Courtesy : Amrit Kaur. Also G.N. 7271 2. LETTER TO SUSHILA NAYYAR February 23, 1940 CHI. SUSHILA, There is no news from you. How is Parachure Shastri? I have written to Biyaniji at Chhindwada. I hope Balkrishna and Kunverji are able to bear the heat. I am keeping perfectly good health. Blessings from BAPU From the Hindi original: Pyarelal Papers. Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Courtesy: Dr. Sushila Nayyar 1 Vide “Speech at Khadi and Village Industries Exhibition”, 20-2-1940 2 Vide “Speech at Gandhi Seva Sangh Meeting—IV”, pp. 22-2-1940 3 For the Congress Working Committee meeting 4 President, Provincial Congress Committee, Nagpur VOL. 78 : 23 FEBRUARY, 1940 - 15 JULY, 1940 1 3. TELEGRAM TO SUSHILA NAYYAR GANDHI SEVA SANGH, February 24, 1940 SUSHILA SEGAON WARDHA TELL VALJIBHAI TAKE MILK TREATMENT WITH REST. -

Kripalani on Gandhiji's Organizational Skills

KCG-Portal of Journals Continuous Issue-29 | December – February 2018 Kripalani on Gandhiji’s Organizational Skills: An overview (A step for sustainable managerial practices effective towards Human Resources Management) Abstract “For Gandhiji organization is not possible without SAMYAMA, discipline, a word which has come into dispute today because of those who utter it themselves lack discipline.”Acharya J.B. Kripalani was a sincere scholar and known as follower of Mahatma Gandhi. He came in touch with Mahatma Gandhi during Chmparan Movement. Kripalaniji observed very closely the adopted by Gandhiji for doing work and guiding people or organization with right perception and right direction. Kripalani was one of the followers of Gandhiji who have faith but not blindly. He criticizes whatever not found as per determine views. His famous book “Gandhi and his life” focuses on various aspects of Gandhian thought in analytical manner. One of the chapters is Gandhi and organization in which he explains organizing capacity and humanitarian wisdom to manage human resource in sustainable manner. People become able to decide right and wrong perception about the things lies with them. They become also enlighten to visualize working capacity, identify and use of inner strengthens it in the interest of an individual, community with survival of universe. In this article, we have tried to know the various examples in which managerial competency of Gandhiji come out. Lastly, we are agreed to keep this statement that Kripalaniji was intellectual follower of Gandhiji who understand his view in right way. These are valuable assets in management field also to those managers who wish get permanent solution of managerial problems, reduce stress and develop harmonious relationship in the organization. -

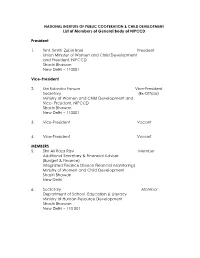

List of Members of General Body of NIPCCD President 1. Smt. Smriti

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC COOPERATION & CHILD DEVELOPMENT List of Members of General Body of NIPCCD President 1. Smt. Smriti Zubin Irani President Union Minister of Women and Child Development and President, NIPCCD Shastri Bhawan New Delhi – 110001 Vice-President 2. Shri Rabindra Panwar Vice-President Secretary (Ex-Officio) Ministry of Women and Child Development and Vice- President, NIPCCD Shastri Bhawan New Delhi – 110001 3. Vice-President Vacant 4. Vice-President Vacant MEMBERS 5. Shri Ali Raza Rizvi Member Additional Secretary & Financial Advisor (Budget & Finance) Integrated Finance Division Financial Monitoring) Ministry of Women and Child Development Shastri Bhawan New Delhi 6. Secretary Member Department of School Education & Literacy Ministry of Human Resource Development Shastri Bhawan New Delhi – 110 001 7. Secretary Member Department of Food & Public Distribution Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution Krishi Bhawan New Delhi – 110 001 8. Secretary Member Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Department of Health & Family Welfare Nirman Bhawan New Delhi- 110011 9. Secretary Member Ministry of Rural Development Department of Rural Development Krishi Bhawan New Delhi – 110 001 10. Secretary Member Ministry of Urban Development Nirman Bhawan New Delhi – 110 011 11. Dr. R.V.P. Singh Senior Research Officer Member NITI Aayog (National Institution for Transforming India Aayog) NITI Bhawan, Parliament Street New Delhi – 110 001 12. Mrs. Anuradh S. Chagti Member Joint Secretary Ministry of Women & Child Development Shastri Bhawan New Delhi – 110 001 13. Secretary Member Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Room No.654, ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan New Delhi – 110 001 14. Secretary Member Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment Shastri Bhawan New Delhi – 110 001 LIST OF STATE SECRETARY 15. -

Scheduled Castes

Directory of Voluntary Organisations SCHEDULED CASTES 2009 Documentation Centre for Women and Children (DCWC) National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development 5, Siri Institutional Area, Hauz Khas, New Delhi – 110016 Number of Copies: 100 Copyright: National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development, 2009 Project Team Project In-charge : Mrs. Meenakshi Sood Project Team : Ms. Alpana Kumari Ms. Renu Computer Assistance : Mrs. Sandeepa Jain Mr. Varun Kumar Acknowledgements : Voluntary Organizations NIPCCD Faculty NIPCCD Regional Centres Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment Ministry of Women and Child Development Ministry of Human Resource Development Planning Commission DISCLAIMER All efforts have been made to verify and collate information about organizations included in the Directory. Information has been collected from various sources, namely directories, newsletters, Internet, proforma filled in by organizations, telephonic verification, letterheads, etc. However, NIPCCD does not take any responsibility for any error that may inadvertently have crept in. The address of offices of organizations, telephone numbers, e-mail IDs, activities, etc. change from time to time, hence NIPCCD may not be held liable for any incorrect information included in the Directory. Foreword Voluntary organizations play a very important role in society. Social development has been ranked high on the priority list of Government programmes since Independence, and voluntary organizations have been equal partners in accelerating