Some Observations on Taiwanese People in Jakarta Ping LIN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPK) Jenjang SMA

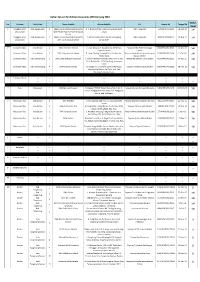

Daftar Satuan Pendidikan Kerjasama (SPK) Jenjang SMA Status No. Provinsi Kab./ Kota Nama Sekolah Alamat Sekolah LPI Nomor SK Tanggal SK Awal 1 Nanggroe Aceh Kota Banda Aceh 1 Satuan Pendidikan Kerjasama (SPK) Jl. T. Nyak Arief No.1 Lamnyong, Banda Aceh Fatih Indonesia 75/MPK.D/KS/2018 09-Feb-18 SN Darussalam SMA Teuku Nyak Arif Fatih Bilingual 23111 School Nanggroe Aceh Kota Banda Aceh 2 Satuan Pendidikan Kerjasama (SPK) Jl. Sultan Malikul Saleh No.103 Lamlagang, Fatih Indonesia 60/MPK.D/KS/2018 02-Feb-18 SN Darussalam SMA Fatih Bilingual School Banda Aceh 2 Sumatera Utara Kota Medan 1 SMA PrimeOne School Jl. Jend. Besar A.H. Nasution No. 50 Medan, Yayasan Putra Putri Naihongga 430/MPK.D/KL/2015 14-Des-15 SN Sumatera Utara Cuilienta Sumatera Utara Kota Medan 2 SMA Sampoerna Academy Jl. Jamin Ginting Komplek Citra Garden, Kec. Yayasan Pendidikan Cahaya Harapan 533/MPK.D/KL/2016 19-Okt-16 SN Medan Baru Bangsa Medan Sumatera Utara Kab. Deli Serdang 3 SMA Cinta Budaya/Chong Wen Jl. Willem Iskandar/Pancing Komp. MMTC Blok Yayasan Pendidikan Cinta Budaya 427/MPK.D/KL/2015 14-Des-15 SN Cinta Budaya No. 1, Deli Serdang, Sumatera Utara Sumatera Utara Kab. Deli Serdang 4 SMA Chandra Kumala Jl. Kelapa no. 1, Komplek Cemara Asri Desa Yayasan Pendidikan Cemara Asri 142/MPK.D/KS/2018 19-Mar-18 SN Sampalu, Kec. Percut Sei Tuan, Kab. Deli Serdang, Sumatera Utara 3 Sumatera Barat ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ 4 Riau Pelalawan 1 SMA Mutiara Harapan Kompleks PT RAPP Rukan Akasia Blok III no. -

2020 Dates of TOCFL (Test of Chinese As a Foreign Language)

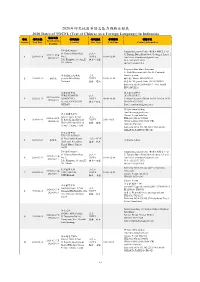

2020年印尼地區華語文能力測驗日程表 2020 Dates of TOCFL (Test of Chinese as a Foreign Language) in Indonesia 報名日期 場次 考試日期 考試地點 考試型式 考試時間 聯繫方式 Registration Session Test Date Location Test Type Test Time Contact Information Deadline Ukrida Kampus 1 Tunghai Education Center (東海大學教育中心) Jl. Tanjung Duren Raya 正式- 2019-12-09至 Jl. Tanjung Duren Raya No 4, Gedung A, Lantai 1 1 2020-01-18 No.4, TOCFL 10:00~12:00 2020-12-27 Email: [email protected] Lab. Komputer, Gedung E, 聽讀-電腦 TEL: (021)2933-5932 Lt3, Jakarta HP:0877-8520-9914 Perguruan Bina Mulia Pontianak Jl. Abdul Rachman Saleh No A1, Pontianak 坤甸高雅文化學院 正式- Contact person: 2 2020-01-11 無開放 Sekolah Bina Mulia TOCFL 10:00~12:00 黄如恩 / Misna 08125672324 Pontianak 聽讀-電腦 林意玲 / Megawati Limin 081253740010 Bank info: BCA 0290100089( YAY PEND BINA MULIA ) 棉蘭菩提學校 蘇北留臺同學會 PERG.BUDDHIS 正式- (ICATI SUMUT) 2019-12-16至 3 2020-02-16 BODHICITTA TOCFL 08:00~10:00 Jl. Brigjen Katamso Dalam No.56E Medan 20151 2020-01-16 JL. SELAM NO.39-41 聽讀-紙本 HP:0878-6711-5599 MEDAN Email: [email protected] Website:www.jtsid.org Email:[email protected] 雅加達臺灣學校 Contact Person:Inda Hsu Jakarta Taipei School 正式- 2020-01-02至 TEL:(021)452-3273 #242 4 2020-02-29 Jl. Raya Kelapa Hybrida TOCFL 9:00~11:00 2020-01-30 HP:0813-8543-5909(MON~FRI Blok QH Kelapa Gading 聽讀-電腦 AM8:00~PM4:00) Permai , Jakarta, 14240 Bank info: BCA 413 302 2212(YAYASAN JAKARTA TAIPEI SCHOOL) 印尼慈濟學校 TZU CHI SCHOOL Jl. -

Economic and Socio-Cultural Relations Between Indonesia and Taiwan: an Indonesian Perspective, 1990-2012

國立中山大學中國與亞太區域研究所 碩士論文 Institute of China and Asia-Pacific Studies National Sun Yat-sen University Master Thesis 印尼與台灣的經濟及社會文化關係(1990-2012):印尼 的觀點 Economic and Socio-Cultural Relations between Indonesia and Taiwan: An Indonesian Perspective, 1990-2012 研究生:陸碧宜 Luh Nyoman Ratih Wagiswari Kabinawa 指導教授﹕顧長永 教授 Prof. Samuel C. Y. Ku 中華民國 102 年 6 月 June 2013 摘摘摘要摘要要要 本文欲分析印尼雖然與台灣沒有政治外交關係,卻能發展其在台灣的經濟 和社會文化關係的原因。印尼與台灣之間的經貿統計顯示,在 2010 年台 灣是印尼的第八大外來投資以及第 11 大貿易夥伴;在社會文化關係方面 的數據更證明在台灣有廣大的印尼移工與印尼學生人口。因此,印尼與台 灣呈現經貿與社會文化互賴的情況。儘管缺乏政治外交關係,為什麼印尼 能持續維持與台灣的經貿以及社會文化關係呢?為解答此問題,本文將採 印尼觀點為途徑,其著重於印尼人民對其與台灣的關係的視角。分析方法 則援引國際關係建構主義中的人民間互動的概念為本,著重觀察共同觀念 和文化價值如何形塑制度,因為制度最終會構築政府的利益。本文證明印 尼在沒有對台外交關係的情況下能持續維持與台灣的經貿和社會文化關係 的原因,在於印尼人民是觀念的倡導者,主導著與台灣之間的互動。人民 與制度兩者對印尼與台灣來說,是深入強化相互關係的經貿與社會文化功 能角色。 關關關鍵關鍵鍵鍵字字字字::::印尼商人,印尼移工,印尼學生,經貿與社會文化關係,人民主 導 i ABSTRACT The main intention of this thesis is to analyses the underlying reason that caused Indonesia is able to nurture its economic and socio-cultural relations with Taiwan, even though under the absence of political diplomatic relations. Statistics on economics between Indonesia and Taiwan shows that in 2010, Taiwan is the eighth-investor and the eleventh- trading partner for Indonesia. Furthermore, statistics on socio-cultural relations proves that there are massive population of Indonesian migrant workers and Indonesian students in Taiwan. Thus, Indonesia and Taiwan are in the conditions of economic and socio-cultural interdependence. Despite lacking political diplomatic relations, why could Indonesia maintain durable economic and socio-cultural relations with Taiwan?” In order to answer that question, this paper will employ the Indonesian perspective approach that stressed on the Indonesian people point of views toward its relations with Taiwan. The main tool of analysis is based on the people-to-people interactions concept which is drawn from the constructivist approach on International Relations. -

IM--Edisi 25 JANUARI 2021.Indd

INTERNATIONAL MEDIA, TTerkaiterkait LLaranganarangan PPerayaanerayaan CCapap GGoo MMeh,eh, MMABTABT KKetapangetapang SSiapiap SSosialisasikanosialisasikan EEdarandaran BBupatiupati KKetapangetapang KETAPANG (IM) - Sekaligus ikut mensosial- wabah Covid 19. Susilo Aheng menilai di Kabupaten Ketapang. Ketua Majelis Adat Budaya isasikan terkait larangan akti- “Kita juga sangat mengerti warga Tionghoa menjadi “Terkait surat edaran bu- Tionghoa (MABT) Kabupaten vitas perayaan Cap Go Meh dan sangat mentaati aturan garda terdepan dalam mem- pati, kami akan mensosialisa- Ketapang Susilo Aheng, Ka- tahun 2021. dari pemerintah. Pandemi bantu pemerintah daerah sikan kepada masyarakat Tion- mis (21/1) lalu memastikan Menurutnya dengan dike- Covid-19 ini adalah tanggung dalam memerangi pandemi ghoa di kabupaten Ketapang pihaknya akan mengikuti surat luarkannya surat edaran terse- jawab kita semua. Mudah- Covid-19. agar tidak merayakan Cap Go edaran Bupati Ketapang Mar- but demi mengendalikan dan mudahan pandemi segara Dia pun berharap virus Meh yang memicu kerumu- tin Rantan. memutus rantai penyebaran berakhir,” kata Susilo Aheng. corona tidak semakin meluas nan,” ujarnya. ● idn/din Ketua MABT Kabupaten Ketapang Susilo Aheng. 19 Tahun Berdirinya Perpetin Cirebon CIREBON (IM) - Paska curkan buku kumpulan sastra Buku kumpulan sastra tersebut Hui, Perpetin Cabang Cirebon Ha Ha”. Juga sering mementas- penulis Tionghoa Cirebon ber- ghoa Cirebon telah lebih dulu reformasi keterbukaan, me- “Xiacheng Fangge”. Kehadiran menghimpun artikel dari lebih terus berkembang. -

Annual Report 2015-2016.Pdf

SEAMEO QITEP in Language Annual Report 2015-2016 Preface This report presents the Centre’s accomplishment in Fiscal Year 2015/2016. During this fiscal year, the Centre conducted various programmes to meet the needs of language teachers and education personnel both in the area of teaching methodology and action research. Also, the Centre has developed teaching/learning materials beneficial to language education. This report serves as the Centre’s accountability for its conduct. It is intended for Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia, SEAMEO Secretariat, stakeholders and public and to keep them updated with the Centre’s programmes and activities. The Centre could not achieve much without the staff’s tireless efforts and hard work. For this reason, I would like to express my appreciation for all staff who have shown their dedication. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to all parties who have supported the Centre throughout the years. Dr Felicia Nuradi Utorodewo Director SEAMEO QITEP in Language Annual Report 2015-2016 i Prioritizing Languages, Advancing Education SEAMEO QITEP in Language Annual Report 2015-2016 ii List of Abbreviations AEC ASEAN Economic Community AISOFOLL Annual International Symposium of Foreign Language Learning CAR Classroom Action Research CDELTEP Centre for Development and Empowerment of Language Teachers and Education Personnel CEFR Common European Framework of Reference CPD Continuing Professional Development ECE Early Childhood Education ILFL Indonesian Language for Foreign Learners MoEC Ministry of Education and Culture MTB-MLE Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education SAR School Action Research SEAQIL SEAMEO QITEP in Language TEFLIN Teaching English as a Foreign Language in Indonesia REGRANT Research Grant SEAMEO QITEP in Language Annual Report 2015-2016 iii i Preface iii List of Abbreviations iv Contents vi Governing Board Members viii Contents Vision Mission KRA II - Regional 24 Goals and Values Visibility A. -

Publikasi Akreditasi Spk Tahun 2019

PUBLIKASI AKREDITASI SPK TAHUN 2019 Pada Tahun 2019, Satuan Pendidikan Kerja Sama (SPK) akan diakreditasi dengan instrumen SPK untuk pertama kalinya. Adapun sasaran akreditasi SPK Tahun 2019 ini adalah sebanyak 250 SPK. Berdasarkan hasil evaluasi terhadap 263 SPK, maka akan direkomendasikan kepada Badan Akreditasi Nasional Sekolah / Madrasah (BAN S/M) sebanyak 150 SPK untuk Tahap I, dan sebanyak 100 SPK lainnya pada Tahap II. Berikut ini adalah daftar 150 SPK yang direkomendasikan untuk diakreditasi tahap I. DAFTAR SATUAN PENDIDIKAN KERJA SAMA UNTUK DIAKREDITASI DI TAHUN 2019 NO NPSN NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT JALAN KOMPLEK PERUM PURI GADING BUILDING SEKTOR B, BR. 1 69856344 SD ASIAN INTERCULTURAL SCHOOL BALI CENGILING, KUTA SELATAN, KAB. BADUNG,BALI SD AUSTRALIAN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL JL. IMAM BONJOL NO. 458A KEL. PEMECUTAN KLOD,KEC. 2 69895373 INDONESIA BALI DENPASAR BARAT, DENPASAR, DENPASAR, BALI JL. DANAU BAYAN 4 NO 15, DENPASAR SELATAN, DENPASAR, 3 69850850 SD BALI ISLAND SCHOOL BALI 4 69854748 SD CANGGU COMMUNITY SCHOOL BANJAR TEGAL GUNDUL, KUTA UTARA, KAB. BADUNG, BALI SD GANDHI MEMORIAL JL TUKAD YEH PENET NO 8A, DENPASAR SELATAN, DENPASAR, 5 69773525 INTERCONTINENTAL SCHOOL BALI BALI 6 69849418 SD GREEN SCHOOL JL. RAYA SIBANGKAJA, ABIANSEMAL, KAB. BADUNG, BALI JL. RAYA SEMAT NO.66 TIBUBENENG BERAWA, KUTA UTARA 7 69856346 SD MONTESSORI BALI BALI, KAB. BADUNG, BALI JL. TUKAD NYALI GG. SMU 6 NO 3 SANUR 80226, DENPASAR 8 69883437 SD SANUR INDEPENDENT SCHOOL SELATAN, DENPASAR, BALI JL. METHASARI BR. PENGUBENGAN KAUH, KUTA UTARA, KAB. 9 69856347 SD SUNRISE SCHOOL BALI BADUNG, BALI JL. LENGKONG KARYA - JELUPANG NO. 58 , SERPONG UTARA, 10 20614918 SD BINA NUSANTARA SERPONG TANGERANG SELATAN, BANTEN BINTARO JAYA SEKTOR IX, JL. -

Pengumuman Pemakalah Dan Peserta Ruang Publik.Pdf

KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN BADAN PENGEMBANGAN BAHASA DAN PERBUKUAN Jalan Daksinapati Barat IV, Rawamangun, Jakarta 13220 Telepon (021) 4750406; Faksimile (021) 4750407 Laman: www.badanbahasa.kemdikbud.go.id; Pos-el: [email protected] Lampiran Pengumuman Nomor : 2329/G3.3/BS/2019 Tanggal: 26 Juli 2019 Pemakalah Seminar dan Lokakarya Pengutamaan Bahasa Negara: Perkuat Pengawasan 5—8 Agustus 2019 Taman Mini Indonesia Indah No. Nama Judul Makalah Instansi 1. Rissari Yayuk Wajah Linguistik di Balai Bahasa Kabupaten Bandung dan Bogor Kalimantan Selatan 2. Endang Sartika Lanskap Bahasa Ruang Publik IAIN Purwokerto, di Kota Purwokerto: Studi Jawa Tengah Kasus Taman Balai Kemambang dan Taman Andhang Pangrengan dalam Aspek Kultural dan Pragmatik 3. Wahyu Damayanti Fenomena Bahasa pada Ruang Balai Bahasa Publik Sepanjang Jalan Kalimantan Barat Protokol Kota Pontianak 4. Agik Nur Efendi Marginalisasi Bahasa: Studi IAIN Madura, Jawa Empiris tentang Visibilitas dan Timur Vitalitas Bahasa di Ruang Publik Kota Surabaya 5. Prof. Dr. I Ketut Darma Penguatan Pengawasan Fakultas Ilmu Laksana, M.Hum. Pengutamaan Bahasa Negara Budaya Universitas di Ruang Publik: Kasus di Udayana, Bali Daerah Pariwisata Kecamatan Nusa Penida 6. Eka Suryatin Penguatan Bahasa Indonesia di Balai Bahasa Ruang Publik: Strategi Kalimantan Selatan Pengembangan Sikap Bahasa Masyarakat Banjar 7. Ni Made Ratnadi Pengaruh Peraturan Gubernur SMP Negeri 5 Bali Nomor 80 Tahun 2018 Tabanan, Bali terhadap Pemartabatan Bahasa Indonesia di Ruang Publik 8. Hary Sulistyo Fanatisme Kedaerahan sebagai Prodi Sastra Dampak Otonomi Daerah dan Indonesia, Fakultas Pengaruhnya terhadap Kondisi Ilmu Budaya, Kebahasaan di Ruang Publik Universitas Sebelas Maret, Jawa Tengah 2 KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN BADAN PENGEMBANGAN BAHASA DAN PERBUKUAN Jalan Daksinapati Barat IV, Rawamangun, Jakarta 13220 Telepon (021) 4750406; Faksimile (021) 4750407 Laman: www.badanbahasa.kemdikbud.go.id; Pos-el: [email protected] No. -

SPK) Jenjang SD

Daftar Satuan Pendidikan Kerjasama (SPK) Jenjang SD Status No. Provinsi Kab./ Kota No. Nama Sekolah Alamat Sekolah LPI Nomor SK Tanggal SK Awal 1 Nanggroe Aceh ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ Darussalam ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ 2 Sumatera Utara Kota Medan 1 SD Medan Independent School Jl. Jamin Ginting Km 10/Jl. Tali Air No. 5, Kel. Yayasan Medan International School 272/ C/ LN/ 2014 26-Nov-14 SI Mangga, Kec. Medan Tuntungan, Medan 20141 Sumatera Utara Kota Medan 2 SD PrimeOne School Jl. Jend. Besar A.H. Nasution No. 88A Medan Yayasan Putra Putri Naihonga 305/ C/ LN/ 2014 27-Nov-14 SN 20147, Sumatera Utara Cuillienta Sumatera Utara Kota Medan 3 SD Singapore School Medan Royal Sumatera Complex, Jl. Jamin Ginting Km. 8,5 Yayasan Pendidikan Singapura 352/ C/ LN/ 2014 02-Dec-14 SN Medan, Sumatera Utara Indonesia Sumatera Utara Kota Medan 4 SD Highscope Indonesia Medan Jl. Bunga Cempaka Psr. III no. 55 Komplek Citra Yayasan Masa Depan Indonesia 278/MPK.D/KL/2016 06-Apr-15 SN Garden Indonesia, Medan Sumatera Utara Kota Medan 5 SD Sampoerna Academy Jl. Jamin Ginting, Komplek Citra Garden, Kec. Yayasan Pendidikan Cahaya 531/MPK.D/KL/2016 19-Okt-16 SN Medan Baru, Medan, Sumatera Utara Harapan Bangsa Medan Sumatera Utara Kab. Deli Serdang 6 SD Cinta Budaya/ Chong Wen Jl. Willem Iskandar Komp. MMTC Blok Cinta Yayasan Pendidikan Cinta Budaya 377/ C/ LN/ 2014 15-Dec-14 SN Budaya No. 1 Medan Estate, Sumatera Utara Sumatera Utara Kab. Deli Serdang 7 SD Kingston School Komp. Graha Metropolitan, Jl. Sumarsono Blok E Yayasan Pendidikan Kesenian Wulan 33/ MPK.C/ KL/2015 29-Jan-15 SN No. -

Profiles Indonesian Provinces.Pdf

About this report In 2007, the Department of Education, Science and Training (DEST) commissioned Morelink Asia Pacific to undertake a study of the international education market in Indonesia. The objective of the study was to identify emerging regions within Indonesia with market potential for Australian education providers. About Australian Education International (AEI) and DEST DEST is an Australian Government Department tasked with providing national educational leadership. DEST works in collaboration with the States and Territories, industry, other agencies and the community in support of the Government’s objectives. AEI works within DEST to integrate the development of international government relations with support for the commercial activities of Australia’s education community. For further information, please visit www.dest.gov.au or www.aei.dest.gov.au DEST/AEI owns exclusive usage rights to this study unless otherwise noted or agreed. Morelink Asia Pacific The research was designed and carried out by Morelink Asia Pacific in collaboration with AEI officials in Australia and Indonesia. The Morelink Asia Pacific research team is headed by Mr Phillip Morey, and includes Yudhi Ismayadi, Ina Liem and Devi Meutia Sari. Acknowledgements AEI would like to thank Morelink Asia Pacific for undertaking this study and all individuals who contributed by agreeing to interviews, supplying data and information, and assisting otherwise. Disclaimer The Commonwealth of Australia, its officers, employees or agents disclaim any responsibility for any loss howsoever caused whether due to negligence or otherwise from the use of information in this publication. No representation expressed or implied is made by the Commonwealth of Australia or any of its officers, employees or agents as to the currency, accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this report. -

List of Membrane Projects Tridome Space Structures

PT BINATAMA AKRINDO LIST OF MEMBRANE PROJECTS TRIDOME SPACE STRUCTURES NO. JOB NO. PROJECT NAME LOCATION FUNCTION STRUCTURE AREA (M2) COMPLETED 1 TD04.070MB Terminal Haji Cengkareng Roof Membrane 520 Des ' 04 2 TD04.087MB Promenade Tent Tenggarong Tent Membrane Structures 138 Des ' 05 3 TD05.091MB La Piazza Kelapa Gading Jakarta Roof Space Frame + Membrane 1.356 May ' 06 4 TD06.072MB Summarecon Mall Serpong Serpong Roof Membrane Structure 810 Jun '07 5 TD08.028MB Sisi Automall Pacific Place Sudirman Jakarta Roof Membrane Structure 1.200 Jul '08 6 TD08.028MB/A Kidzania Tent - Pacific Place Jakarta Roof Membrane Structure 160 Oct '08 7 TD08.012MB-I Danau Buatan - Amphitheatre Pekanbaru Roof Membrane Structure 105 Dec '08 8 TD08.012MB-II Danau Buatan - Entrance Gate Pekanbaru Roof Membrane Structure 245 Dec '08 9 TD08.057MB Club Med Bali Bali Roof Membrane Structure 171 Dec '08 10 TD04.102MB/TR Regatta Apartment Jakarta Tent/Ornamen Membrane Struc. + SS Rod 1.162 Jun '09 11 TD09.052MB Sally Port Area & Covered Wals Jakarta Roof Membrane Structures 55 Jun '09 12 TD09.039MB London School Jakarta Roof Membrane Structures 21 Jul '09 13 TD09.098MB Sally Port Back Entrance US Embassy Jakarta Roof Space Frame + Membrane 141 Jan '10 14 TD10.071MB Tenda Senopati Jakarta Membrane Membrane 75 Aug '10 15 TD10.059MB Paspampres Jakarta Roof Membrane 75 Okt '10 16 TD10.061MB Kantor Gubernur Provinsi Jawa Timur Surabaya Roof Membrane Structures 53 Des '10 17 TD09.045MB Membrane rumah panggung, Danau Buatan Pekanbaru Riau Roof Membrane Structures 345 Des -

能力測驗 2020 Test of Chinese As 華a Foreign Language(TOCFL)In Indonesia

Taipei Economic and Trade Office in Indonesia 語文能力測 驗 2020 Test of Chinese as 華a Foreign Language(TOCFL)in Indonesia Tempat dan Tanggal Ujian 1 Jakarta : Jakarta Taipei School(2/29、4/18 6/6、10/10、12/12)、Ukrida Kampus 1(1/18、 3/14、5/16、7/11、9/12、11/14) 2 Surabaya : Surabaya Taipei School(4/18、6/6、 9/12、11/14) 3 Medan : ICATI SUMUT(2/16、5/10、9/13、 11/22) 4 Batam : Universitas Universal(3/15、5/17、9/13) 5 Yogyakarta : Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta (6/13、11/14) 6 Pontianak : Sekolah Bina Mulia Pontianak(1/11、 4/25) 7 Riau : ICATI Riau(5/2、8/1) 8 Semarang : Mandiri Bahasa Semarang(4/26、 11/15) 9 Bandung : Badan Koordinasi Pendidikan Bahasa Mandarin Jawa Barat(4/18 ) 1.URL pendaftaran online : https://tocfl.sc-top.org.tw/zoom/index.php 2.Untuk informasi pembayaran dan kontak masing-masing pelaksanaan ujian, Biaya Ujian silakan dilihat di website divisi pendidikan TETO https://studiditaiwan. blogspot.com/ Biaya ujian : komputer Rp300,000; kertas Rp200,000 3.Aplikasi visa bagi siswa tingkat S1 di Taiwan (pengajarannya menggunakan Mandarin) harus menyertakan sertifikat TOCFL A2. (harga yang sama untuk versi Traditional dan Simplified) 4.Pendaftaran ujian TOCFL tahun 2020 dilakukan secara online dan pembayaran via transfer. Jika tidak dapat mendaftar secara online ataupun pembayaran via transfer, silakan hubungi setiap area ujian untuk mendaftar Tingkatan Ujian dan membayar secara langsung. 5. Hasil ujian akan diumumkan sekitar 1 bulan setelah tanggal ujian, serta transkrip nilai dan sertifikat dapat diperoleh sekitar 2 bulan setelahnya. -

Data Satuan Pendidikan Kerja Sama Pendidikan Anak Usia Dini (Spk Paud)

DATA SATUAN PENDIDIKAN KERJA SAMA PENDIDIKAN ANAK USIA DINI (SPK PAUD) Jenjang Jangka Wakru MoU Surat Permohonan Pengajuan Perpanjangan SPK PAUD SK Nomor Tanggal SK Asal Kategori No NAMA SEKOLAH PROV LPA LPI Perpanjangan Perpanjangan LPA Pelaksanaan KB TK Lama Dari Sampai No Surat Permohonan Tanggal Perihal Tak 06 November 17 Okober Permohonan Perpanjangan Ijin SPK TK 1 Green School 001/MPK.C/PM/2017 TK Bali Cambride Inggris Green School Pengelolaan Terbatas 187/X/YKK/2017 2017 2017 Green School Waktu Council For The Indian 06 November Yayasan Rama Internasional 26 Oktober Permohonan Perpanjangan Izin SPK No. 2 Rama Global School 002/MPK.C/PM/2017 TK Jabar School Certificate India Penyelenggaraan 3 Tahun 2017 2019 077/RGS/ADMIN/2017-18/02526 2017 School 2017 206/MPK.B1/DU/2014 Examinations Permohonan Perpanjangan Izin Canggu Community 06 November 31 Januari 3 003/MPK.C/PM/2017 TK Bali Open Government License Inggris Canggu Community Schooll Pengelolaan 5 Tahun 2014 2019 004/YSI/ADM/I/2017 Operasional TK Canggu Community School 2017 2017 School Permohonan Perpanjangan Izin Canggu Community 06 November 31 Januari 4 004/MPK.C/PM/2017 KB Bali Open Government License Inggris Canggu Community Schooll Pengelolaan 6 Tahun 2014 2019 003/YSI/ADM/I/2017 Operasional KB Canggu Community School 2017 2017 School 06 November Little River Primary 10 Oktober Pengajuan Permohonan Perpanjangan Izin 5 Sunrise School 005/MPK.C/PM/2017 TK Bali Australia Sunrise School Penyelenggaraan 4 Tahun 2014 2017 187/YAMACK/X/2017 2017 School 2017 TK dan KB SPK Sunririse