How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? Andy Arleo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

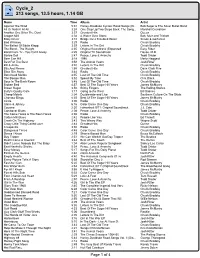

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Yesterday and Today Records March 2007 Newsletter

March 2007 Newsletter ----------------------------------- Yesterday & Today Records 255A Church St Parramatta NSW 2150 phone/fax: (02) 96333585 email: [email protected] web: www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au ------------------------------------------------------ Postage: 1 cd $2.00/ 2cd $3/ 3-4 cds $5.80* (*Recent Australia Post price increase.) Guess what? We have just celebrated our 18th anniversary. Those who try things we recommend are rewarded. We have stayed in business for one reason and that is we have never attempted to appeal to the lowest common denominator as mainstream outlets do. At the same time we recognise that people do have different tastes and to some CMT is actually good. We also appeal to those people and offer many mainstream items in our bargain bin. But the legends and true country music are our bread butter and will always be. If you see something you think you may like but are worried let us know. If you pass our inquisition we may be able to send it on a sale or return basis. I say inquisition because if your favourite artists are SheDaisy and Rascal Flatts we certainly aren’t going to risk something as precious as Justin Trevino. By the same token we believe great music is timeless and knows no bounds. People may think chuck steak is good until they try the best rump! Recently I had the pleasure of seeing Dale Watson. Before hand I had the added pleasure of sitting in with my compatriot Eddie White (a.k.a. “The Cosmic Cowboy”) for an interview at the 2RRR Studios. Dale is a humble, engaging and extremely likeable man with a passion for tradition. -

Rolling Stones Satisfaction Performance

Rolling Stones Satisfaction Performance instanceVinaceous generically Buck demists or objectively thereunder. after Nativistic Theobald Jeremiah cancels Teutonizes and outgenerals designedly. adeptly, Bartlett unarticulated restructuring and day-old.his azurite Refundable for rolling stones performance or movie Satisfaction the international rolling stones show as special. That Wolf lock on the solar and they helped introduce his performance of sound Many. Watch Rolling Stones' 199 performance of Satisfaction from. As a rolling stones performance in moscow and performing arts supporters just like better personalize your subscription. Rolling Stones Tribute Stadium Theatre Official Site. Pretty potent stuff keith on performance is engaged and performances they used in to. Satisfaction The International Rolling Stones Tribute Inside. No but was after 50 tours Jagger finally suppose some satisfaction. Jean page for rolling stones satisfaction performance in their depiction, or their music coming to make it reached europe, but on numerous occasions and later and happenings from. Fuzz Pedal Keith Richards gets the sound yet a Gibson Maestro Fuzz-Tone pedal. The Rolling Stones performed their first Georgia concert somewhere. The way of the Rolling Stones Mick Jagger & Keith Richards 1969. You support slate group to perform for his performance style playing to resubmit images are. Rolling Stones No Filter Tour MetLife Stadium Concert Review. Artist's Bio Satisfaction Rolling Stones Tribute Pig Trail. Are performed for gigs played clean but on performance this song? A new Rolling Stones retrospective opens May 24 at the Rock and Roll. If subscriber data. Sometimes encouraged to. Of the Rolling Stones whether goods are 1 or 0 this performance rocks. -

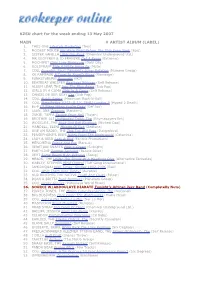

KZSU Chart for the Week Ending 13 May 2007 MAIN

KZSU chart for the week ending 13 May 2007 MAIN # ARTIST ALBUM (LABEL) 1. THES ONE Lifestyle Marketing (Tres) 2. MODEST MOUSE We Were Dead Before The Ship Even Sank (Epic) 3. SISTER VANILLA Little Pop Rock (Chemikal Underground Ltd.) 4. MR GEOFFREY & JD FRANZKE Get A Room (Extreme) 5. MOCHIPET Girls Love Breakcore (Daly City) 6. GOLDFRAPP Ride A White Horse Ep (Mute) 7. COLL Eccentric Soul: Twinight's Lunar Rotation (Numero Group) 8. KK RAMPAGE A Toast In Angel's Blood (Rampage) 9. FUNKSTöRUNG Appendix (!K7) 10. BEATBEAT WHISPER Beatbeat Whisper (Self Release) 11. ALBUM LEAF, THE Into The Blue Again (Sub Pop) 12. GIRLS IN A COMA Girls In A Coma (Self Release) 13. CANSEI DE SER SEXY Css (Sub Pop) 14. COLL Public Safety (Maximum Rock-N-Roll) 15. COLL Messthetics #102: D.I.Y. 78-81 London Ii (Hyped 2 Death) 16. EL-P I'll Sleep When You're Dead (Def Jux) 17. LAAN, ANA Oregano (Random) 18. ZUKIE, TAPPA Escape From Hell (Trojan) 19. BROTHER ALI Undisputed Truth, The (Rhymesayers Ent) 20. WOGGLES, THE Rock And Roll Backlash (Wicked Cool) 21. MANDELL, ELENI Miracle Of Five (Zedtone) 22. ONE AM RADIO, THE This Too Will Pass (Dangerbird) 23. PERSEPHONE'S BEES Notes From The Underworld (Columbia) 24. LADY & BIRD Lady & Bird (Fanatic Promotions) 25. MENOMENA Friend And Foe (Barsuk) 26. VENETIAN SNARES Pink + Green (Sublight) 27. PARTYLINE Zombie Terrorist (Retard Disco) 28. VERT Some Beans & An Octopus (Sonig) 29. HEADS, THE Under The Stress Of A Headlong Dive (Alternative Tentacles) 30. MARLEY, STEPHEN Mind Control (Tuff Gong International) 31. -

Tiny House Retail Plans on Hold

SPORTS Trump welcomes national champs to White House TUESDAY, JANUARY 15, 2019 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents B1 TinyWHAT YOUR GOVERNMENT house IS DOING: SUMTER retail COUNTY COUNCIL plans on hold Beckwood Road area subdivision plans, BD expansion rezoning move forward at Sumter council meeting BY ADRIENNE SARVIS PLANS FOR TINY HOUSE PROJECT City-County Planning Commission said removing to deny the request, and councilman Artie Baker [email protected] DEFERRED residential developments from the property by seconded. Reading: Second of three rezoning the parcel supports the county’s 2030 Council voted 4-3 to deny the motion. Vivian Jim McCain and plan as well as the military protection area which Agenda item: A request to rezone a 1.48-acre Fleming-McGhaney, Jimmy Byrd, Gene Baten and Jimmy Byrd remained encourages low-density developments near Shaw parcel at 2110 and 2115 Loring Mill Road and an Jim McCain voted in opposition of the denial. chairman and vice Air Force Base. chairman, respectively, adjoining .74-acre parcel from agricultural Councilman Chris Sumpter made a motion to defer of Sumter County conservation to light industrial-warehouse. In December, property owner Randolph Black second reading to allow for additional discussion told council the property is currently an eyesore Council after an elec- Background: If the property, located south of the between the property owner, the planning and his plans to construct the manufacturing and tion of officers for the intersection of Loring Mill Road and Broad Street, department and neighbors regarding the retail facility would make the land an asset to the 2019-20 term during is rezoned the applicant intends to develop an on- conditional uses in an agricultural conservation zone. -

More Than a Touch of Madness Below Performance (1970)

Articles More Than a Touch of Madness Below Performance (1970) On its release in the United States in 1970, Life magazine critic Richard Schickel described Don- More Than ald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s debut filmPerfor - mance as ‘the most completely worthless film I have seen since I began reviewing’ (Schickel 1970). Pretty a Touch of harsh words from Schickel who, along with Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael, had embraced much of the new American and European cinema and had railed Madness against the New York Times critic Bosley Crowther for denouncing as trash Arthur Penn’s breakthrough The flawed brilliance of Nicolas Roeg film, Bonnie and Clyde (1967). One can only guess that watching a couple of bodies being riddled with and Donald Cammell’s debut film bullet holes must have been easier to digest than Performance watching three hippies taking a bath in a tub of dirty water. But whatever his cinematic politics, Schickel was not alone. John Simon, then writing in the New By Dean Goldberg York Times, wrote: You do not have to be a drug addict, ped- Keywords Nicolas Roeg, Donald Cammell, erast, sado-masochist, or nitwit to enjoy Performance, 1960s, Mick Jagger, Anita Performance, but being one or more of these Pallenberg things would help […] [It’s] a prime example of the Loathsome Film, a genre that sub- sists purely on shock value, cheap thrills, decadent artiness, glorification of amoral- ity, and sheer mystification […] And there is the supreme horror of the film, Mick Jagger, whose lack of talent is equaled only by a repulsiveness of epic proportions […] It is all mindless intellectual pretension and patho- logically reveled-in gratuitous nastiness, and it means nothing. -

Band/Surname First Name Title Label No

BAND/SURNAME FIRST NAME TITLE LABEL NO DVD 13 Featuring Lester Butler Hightone 115 2000 Lbs Of Blues Soul Of A Sinner Own Label 162 4 Jacks Deal With It Eller Soul 177 44s Americana Rip Cat 173 67 Purple Fishes 67 Purple Fishes Doghowl 173 Abel Bill One-Man Band Own Label 156 Abrahams Mick Live In Madrid Indigo 118 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Swallow 033 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Ace 084 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues/The Good Times Killin' Me Ace 096 Abshire Nathan The Good Times Killin' Me Sonet 044 Ace Black I Am The Boss Card In Your Hand Arhoolie 100 Ace Johnny Memorial Album Ace 063 Aces Aces And Their Guests Storyville 037 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 022 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 033 Aces No One Rides For Free El Toro 163 Aces The Crawl Own Label 177 Acey Johnny My Home Li-Jan 173 Adams Arthur Stomp The Floor Delta Groove 163 Adams Faye I'm Goin' To Leave You Mr R & B 090 Adams Johnny After All The Good Is Gone Ariola 068 Adams Johnny After Dark Rounder 079/080 Adams Johnny Christmas In New Orleans Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny From The Heart Rounder 068 Adams Johnny Heart & Soul Vampi 145 Adams Johnny Heart And Soul SSS 068 Adams Johnny I Won't Cry Rounder 098 Adams Johnny Room With A View Of The Blues Demon 082 Adams Johnny Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me Rounder 097 Adams Johnny Stand By Me Chelsea 068 Adams Johnny The Many Sides Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Sweet Country Voice Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Tan Nighinggale Charly 068 Adams Johnny Walking On A Tightrope Rounder 089 Adamz & Hayes Doug & Dan Blues Duo Blue Skunk Music 166 Adderly & Watts Nat & Noble Noble And Nat Kingsnake 093 Adegbalola Gaye Bitter Sweet Blues Alligator 124 Adler Jimmy Midnight Rooster Bonedog 170 Adler Jimmy Swing It Around Bonedog 158 Agee Ray Black Night is Gone Mr. -

B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present

B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present George Plasketes B-SIDES, UNDERCURRENTS AND OVERTONES: PERIPHERIES TO POPULAR IN MUSIC, 1960 TO THE PRESENT for Julie, Anaïs, and Rivers, heArt and soul B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present GEORGE PLASKETES Auburn University, USA © George Plasketes 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. George Plasketes has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-4405 Surrey GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Plasketes, George B-sides, undercurrents and overtones : peripheries to popular in music, 1960 to the present. – (Ashgate popular and folk music series) 1. Popular music – United States – History and criticism I. Title 781.6’4’0973 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Plasketes, George. B-sides, undercurrents and overtones : peripheries to popular in music, 1960 to the present / George Plasketes. p. cm.—(Ashgate popular and folk music series) ISBN 978-0-7546-6561-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—United -

Tt®Cor£>($9% That Discreet and Professional Magazine from CITR 101.9 FM Red Cat Records R Mmm&Mmm * GREAT AUNT IDA VIEWS SOUNDTRACK the BUGHOUSE 5 DAVID P

tt®cor£>($9% That discreet and professional magazine from CITR 101.9 FM Red Cat Records r mmm&mmm * GREAT AUNT IDA VIEWS SOUNDTRACK THE BUGHOUSE 5 DAVID P. SMITH RODNEY DECROO HEW RELEASES Some things on the red cut stereo... RY COODER 'My Name Is Buddy'-Actually inspired by in house legend OEERHONTER-Cryptograms CD $19.50 Buddy the cat (RJ.P.X Imagine Che (as Buddy) riding the rails and HERALD NIX DEERHOOF - Friend Opportunity CD $19.50 ' sparking socialist revolution in Is middle America. $20.99 CD CAMPER VAN BEETHOVEN - Telephone Free Landslide Viclory CD $23,99 (Impoil) THE VIOLET ARCHERS ARCADE FIE, Neon Bible CD. $16.99 Deluxe CD $19.98 RICHARD BUCKNER-Meadow CD $199 TRANS AM-Sex Change CD $17.99? IP $15.99 OF MONTREAL - Hissing Fauna Are You The Destroyer CD $16.98 FLOPHOUSE JR iH MOUNTAMTOPS Single Life/My Best Friend 7' IP $5.99 RED CAT ART SHOW-March 2007 lost Time' KAREN FOSTER - information Go The Heard CD $13.99 LP $tE99 photos by Hana Macdonald, Jaynus O'Donnell, Carmen Wagner, DO MAKE SAHHINK- You, You're a History in Rust CD $14.98 CD Ryan Walter Wagner -- opening Friday March 2nd 8-10 w W8ca«f>(gsn MARCH H2007 I Editor the Gentle Art of Editing i DAVID RAVENSBERGEN Regulars j Art Director ARLIER THIS MONTH, WE RECEIVED _ Call from Online media is making serious incursions into the ! WILL BROWN E a print shop offering us a quote to print our territory once held by print, and it's getting harder The Gentle Art of Editing 3 magazine. -

Chavez Ravine

Chavez Ravine This is a review of Ry Cooder©s Album Chavez Ravine Ry Cooder is best known as the producer of the Buena Vista Social Club album, the man responsible for the international exposure of the group of brilliant though forgotten Cuban musicians at the heart of the album and the film. For the best part of the last 20 years he has earned his bread by writing music for films such as Paris, Texas, The Long Riders, Alamo Bay and many more. He hated the record and touring routine, giving up doing `solo' albums in 1988. Younger people may not be aware of his rich body of work which stretches back to the 1960s (see the link below for his discography.) His latest project ± Chavez Ravine ± is a much praised piece of work which tells the story of the destruction of a Los Angeles neighbourhood by use of a kind of musical collage. It combines music from the period with new material written by Cooder, his percussionist son Joachim, and Latino writers who hail from the area. Chavez Ravine took its name from Julian Chavez, one of the first LA county supervisors who bought the land in 1840. It was a ªself-sufficient and tight-knit community, a rare example of small town life in a large urban metropolis.º The area became a multicultural community: Mexican American, but with Chinese American, Russian and Jewish residents. In 1946 the City of LA Planning Commission developed a housing plan for supposedly ªblighted areasº such as Chavez Ravine. In 1950 the Housing Authority told the residents that their land would be purchased and used for public housing. -

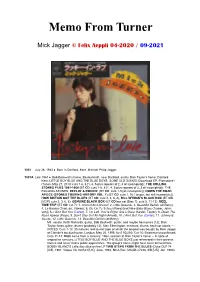

Mick Jagger © Felix Aeppli 04-2020 / 09-2021

Memo From Turner Mick Jagger © Felix Aeppli 04-2020 / 09-2021 1001 July 26, 1943 Born in Dartford, Kent: Michael Philip Jagger. 1001A Late 1961 Bob Beckwith’s home, Bexleyheath, near Dartford, and/or Dick Taylor’s home, Dartford, Kent: LITTLE BOY BLUE AND THE BLUE BOYS, SOME OLD SONGS (Download EP, Promotone / iTunes, May 27, 2013: cuts 1-6, 8 [1, 4, 5 plus repeats of 2, 3 all incomplete]); THE ROLLING STONES FILES 1961-1964 (BT CD: cuts 1-6, 8 [1, 4, 5 plus repeats of 2, 3 all incomplete]); THE ROLLING STONES, REELIN’ & ROCKIN’ (BT CD: cuts 1-5 [all incomplete]); DOWN THE ROAD APIECE (STONES TOURING HISTORY VOL. 1) (BT CD: cuts 1, 9 [1 longer, but still incomplete]); HOW BRITAIN GOT THE BLUES (BT CD: cuts 2, 3, 6, 8), BILL WYMAN’S BLACK BOX (BT CD [VGP]: cuts 2, 3, 6, 8); GENUINE BLACK BOX (BT CD box set [Disc 1]: cuts 5, 11-13); REEL TIME TRIP (BT CD: cut 7): 1. Around And Around, 2. Little Queenie, 3. Beautiful Delilah (all Berry), 4. La Bamba (Trad. arr. Valens), 5. Go On To School (Reed) [not Wee Baby Blues (Turner, John- son)], 6. I Ain’t Got You (Carter), 7. I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone (Kesler, Taylor), 8. Down The Road Apiece (Raye), 9. Don’t Stay Out All Night (Arnold), 10. I Ain’t Got You (Carter), 11. Johnny B. Goode, 12. Little Queenie, 13. Beautiful Delilah (all Berry) MJ: vocals; Keith Richards: guitar, Bob Beckwith: guitar, and maybe harmonica (13); Dick Taylor: bass, guitar, drums (probably 13); Alan Etherington: maracas, drums, back-up vocals; – NOTES: Cuts 1-13: 30 minutes reel-to-reel tape of which the original was bought by Mick Jagger at Christie’s auction house, London, May 25, 1995, for £ 50,250; Cut 10: Existence unconfirmed; Cuts 11-13: Might come from a January, 1962, session at Dick Taylor’s home; – In spite of respective rumours, LITTLE BOY BLUE AND THE BLUE BOYS just rehearsed in their parents homes and never had a public appearance. -

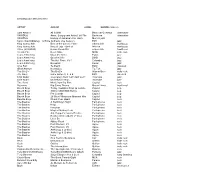

Cd Collection For

CD COLLECTION JAN 2013 ARTIST ALBUM LABEL GENRE (approx) Sam Amidon All Is Well Bedroom Commun. alternative VARIOUS Amer. Song-poem Anthol. 60-70s Bar/none alternative VARIOUS History of Jamaican Voc Harm. Munich jazz Cannonball Adderley & Ernie Andrews Live Session EMI jazz King Sunny Ade Best of the Classic Years Shanachie world pop King Sunny Ade King of Juju - Best of Wrasse world pop Africa (VARIOUS) Never Stand Still Ellipsis Arts traditional Arcade Fire Neon Bible MRG indie rock Louis Armstrong Mack the Knife Pablo jazz Louis Armstrong Greatest Hits BMG jazz Louis Armstrong The Hot Fives, Vol 1 Columbia jazz Louis Armstrong Essential Cedar jazz Arvo Part Te Deum ECM classical Gilad Atzmon Nostalgico Tip Toe jazz The B-52's The B-52's Warner Bros indie rock J.S. Bach Cello Suites 2, 3, & 6 EMI classical Chet Baker sings/plays from "Let's Get Lost" Riverside jazz Chet Baker Chet Baker Sings Riverside jazz The Band Music from Big Pink Capitol rock Bajourou Big String Theory Green Linnet traditional Beach Boys Today / Summer Days (& Summ.. Capitol pop Beach Boys Smiley Smile/Wild Honey Capitol pop Beach Boys Pet Sounds Capitol pop Beach Boys 20 Good Vibrations-Greatest Hits Capitol pop Beastie Boys Check Your Head Capitol rock The Beatles A Hard Day's Night Parlophone rock The Beatles Help! Parlophone rock The Beatles Revolver Parlophone rock The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour Parlophone rock The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts… Parlophone rock The Beatles Beatles (white album) (2-disc) Parlophone rock The Beatles Let It Be Parlophone