Assessing Consumer Preferences of Scab-Resistant Apples: a Sensory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

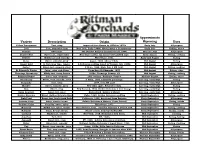

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

APPLE (Fruit Varieties)

E TG/14/9 ORIGINAL: English DATE: 2005-04-06 INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NEW VARIETIES OF PLANTS GENEVA * APPLE (Fruit Varieties) UPOV Code: MALUS_DOM (Malus domestica Borkh.) GUIDELINES FOR THE CONDUCT OF TESTS FOR DISTINCTNESS, UNIFORMITY AND STABILITY Alternative Names:* Botanical name English French German Spanish Malus domestica Apple Pommier Apfel Manzano Borkh. The purpose of these guidelines (“Test Guidelines”) is to elaborate the principles contained in the General Introduction (document TG/1/3), and its associated TGP documents, into detailed practical guidance for the harmonized examination of distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS) and, in particular, to identify appropriate characteristics for the examination of DUS and production of harmonized variety descriptions. ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS These Test Guidelines should be read in conjunction with the General Introduction and its associated TGP documents. Other associated UPOV documents: TG/163/3 Apple Rootstocks TG/192/1 Ornamental Apple * These names were correct at the time of the introduction of these Test Guidelines but may be revised or updated. [Readers are advised to consult the UPOV Code, which can be found on the UPOV Website (www.upov.int), for the latest information.] i:\orgupov\shared\tg\applefru\tg 14 9 e.doc TG/14/9 Apple, 2005-04-06 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. SUBJECT OF THESE TEST GUIDELINES..................................................................................................3 2. MATERIAL REQUIRED ...............................................................................................................................3 -

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Germplasm Sets and Standardized Phenotyping Protocols for Fruit Quality Traits in Rosbreed

Germplasm Sets and Standardized Phenotyping Protocols for Fruit Quality Traits in RosBREED Jim Luby, Breeding Team Leader Outline of Presentation RosBREED Demonstration Breeding Programs Standardized Phenotyping Protocols Reference Germplasm Sets SNP Detection Panels Crop Reference Set Breeding Pedigree Set RosBREED Demonstration Breeding Programs Clemson U WSU Texas A&M UC Davis U Minn U Arkansas Rosaceae Cornell U WSU MSU MSU Phenotyping Affiliates USDA-ARS Driscolls Corvallis Univ of Florida UNH Standardized Phenotyping Protocols Traits and Standardized Phenotyping Protocols • Identify critical fruit quality traits and other important traits • Develop standardized phenotyping protocols to enable data pooling across locations/institutions • Protocols available at www.RosBREED.org Apple Standardized Phenotyping Firmness, Crispness – Instrumental, Sensory Sweetness, Acidity – Intstrumental, Sensory Color, Appearance, Juiciness, Aroma – Sensory At harvest Cracking, Russet, Sunburn Storage 10w+7d Storage 20w+7d Maturity Fruit size 5 fruit (reps) per evaluation Postharvest disorders Harvest date, Crop, Dropping RosBREED Apple Phenotyping Locations Wenatchee, WA St Paul, MN Geneva, NY • One location for all evaluations would reduce variation among instruments and evaluators • Local evaluations more sustainable and relevant for future efforts at each institution • Conduct standardized phenotyping of Germplasm Sets at respective sites over multiple (2-3) seasons • Collate data in PBA format, conduct quality control, archive Reference -

Handling of Apple Transport Techniques and Efficiency Vibration, Damage and Bruising Texture, Firmness and Quality

Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences PUBLISHED BY: B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACTIVITIES OF WP9 IN THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE AGROPHYSICS CONTRACT NO: QLAM-2001-00428 CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR APPLIED PHYSICS IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE WITH THE th ACRONYM AGROPHYSICS IS FOUNDED UNDER 5 EU FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH, TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES GENERAL SUPERVISOR OF THE CENTRE: PROF. DR. RYSZARD T. WALCZAK, MEMBER OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PROJECT COORDINATOR: DR. ENG. ANDRZEJ STĘPNIEWSKI WP9: PHYSICAL METHODS OF EVALUATION OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE QUALITY LEADER OF WP9: PROF. DR. ENG. BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI, JR. REVIEWED BY PROF. DR. ENG. JÓZEF KOWALCZUK TRANSLATED (EXCEPT CHAPTERS: 1, 2, 6-9) BY M.SC. TOMASZ BYLICA THE RESULTS OF STUDY PRESENTED IN THE MONOGRAPH ARE SUPPORTED BY: THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNDER GRANT NO. 5 P06F 012 19 AND ORDERED PROJECT NO. PBZ-51-02 RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF POMOLOGY AND FLORICULTURE B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ©Copyright by BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LUBLIN 2006 ISBN 83-89969-55-6 ST 1 EDITION - ISBN 83-89969-55-6 (IN ENGLISH) 180 COPIES, PRINTED SHEETS (16.8) PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER IN POLAND BY: ALF-GRAF, UL. -

Effect of Cultivar, Position of Fruits in Tree-Crown and of Summer Pruning on Surface Temperature of Apples and Pears, Ejpau, 15(2), #03

Electronic Journal of Polish Agricultural Universities (EJPAU) founded by all Polish Agriculture Universities presents original papers and review articles relevant to all aspects of agricultural sciences. It is target for persons working both in science and industry, regulatory agencies or teaching in agricultural sector. Covered by IFIS Publishing (Food Science and Technology Abstracts), ELSEVIER Science - Food Science and Technology Program, CAS USA (Chemical Abstracts), CABI Publishing UK and ALPSP (Association of Learned and Professional Society Publisher - full membership). Presented in the Master List of Thomson ISI. ELECTRONIC 2012 JOURNAL Volume 15 OF POLISH Issue 2 AGRICULTURAL Topic HORTICULTURE UNIVERSITIES Copyright © Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego we Wrocławiu, ISSN 1505-0297 LIPA T., LIPECKI J., JANISZ A., 2012. EFFECT OF CULTIVAR, POSITION OF FRUITS IN TREE-CROWN AND OF SUMMER PRUNING ON SURFACE TEMPERATURE OF APPLES AND PEARS, EJPAU, 15(2), #03. Available Online http://www.ejpau.media.pl EFFECT OF CULTIVAR, POSITION OF FRUITS IN TREE-CROWN AND OF SUMMER PRUNING ON SURFACE TEMPERATURE OF APPLES AND PEARS Tomasz Lipa, Janusz Lipecki, Anna Janisz Departament of Pomology, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Poland ABSTRACT Extensive studies (2006–2009) on the influence of apple and pear fruit surface temperature, in dependence on the fruit position in tree canopy and summer pruning, were conducted in a commercial orchard in Lublin district, Poland. There was a significant effect of fruit position in the canopy on heat accumulation in fruit surface. Fruits born in southern part of the canopy were more heated than those from other tree parts. It was found that a blush contributed to an increase of fruit temperature, especially those from southern parts of the canopy. -

30 Kellerhals.Rtf

Archived at http://orgprints.org/8932/ Evaluation of apple fruit quality within the EU project Hidras Beurteilung der Fruchtqualität beim Apfel im Rahmen des EU-Projektes Hidras Markus Kellerhals and Christian Eigenmann1 Abstract The EU project Hidras (High Quality Disease Resistant Apples for a sustainable agriculture, QLK5-CT-2002- 01-01492) aims to identify genetic factors controlling apple fruit quality with the objective of increasing the acceptability of disease resistant apples. At Agroscope Changins-Wädenswil (ACW) we are performing ex- pert panel tests and consumer tests. The consumer inquiry during the public fair BEA 2005, end of April 2005 in Bern, Switzerland, resulted in comprehensive information on consumption trends in apple for differ- ent age groups. This work is coordinated with partners in Poland and Belgium. All the age groups considered flavour, juiciness and firmness as very important quality criteria for apples. The preference of apples to other fruit such as pears, bananas or citrus is more significant with adults and especially elder people. However, apple was the most favourite fruit species for all age classes. Almost one third of the adults prefer an apple to other snacks. On the other hand, children prefer chips and popcorn and only 12% prefer an apple to other snacks. The overall appearance and eating quality of scab resistant varieties (Ariane, Topaz and Goldrush) and non- resistant varieties (Gala, FAW 5878 and La Flamboyante) evaluated by the same consumers confirmed, that the resistant varieties were competitive in respect to fruit quality with the non-resistant varieties. Keywords: apple, breeding, consumer test, scab resistance, fruit quality Introduction The success of newly developed disease resistant apple varieties is largely dependent on their fruit quality. -

Consumer Evaluation of New, Antique, and Little Known Apple Varieties

Consumer Evaluation of New, Antique, and Little Known Apple Varieties Duane W. Greene and Jon M. Clements Department of Plant, Soil, and Insect Sciences, University of Massachusetts Introduction for them. Honeycrisp is an example of an apple that not only has become extremely popular, but Massachusetts has had a long history of apple Massachusetts appears to be a favorable place to grow production. Due to its favorable climate, it has been a this apple. leading producer in the United State of the variety In the past, private breeders, University breeding McIntosh, along with Maine, Vermont, and New York. programs, and nurseries received compensation for Over the past few years, the dynamics of apple patented varieties by receiving royalties from the sale production has changed dramatically due in large part of trees. Because apple breeding programs are very to the rapid expansion of apple production overseas, expensive to operate, the royalties received were especially in the southern hemisphere and a logarithmic insufficient to cover the cost to maintain a breeding increase in production in China. While Massachusetts program. Undoubtedly, new varieties will be released has a climate that favors the production of high quality in the future in an entirely different way. Tree sales, apples, return to growers has declined steadily over production, and marketing of the best and most the past 20 years. Other geographic locations can promising varieties will be under the strict control of produce nearly twice as many apples per acre because patent holders. Trees will be sold only to large growers of high light conditions, a long growing season, and willing to sign agreements, and they will probably be abundant water. -

INF03 Reduce Lists of Apple Varieites

ECE/TRADE/C/WP.7/GE.1/2009/INF.3 Specialized Section on Standardization of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Fifty-fifth session Geneva, 4 - 8 May 2009 Items 4(a) of the provisional agenda REVISION OF UNECE STANDARDS Proposals on the list of apple varieties This note has been put together by the secretariat following the decision taken by the Specialized Section at its fifty-fourth session to collect information from countries on varieties that are important in international trade. Replies have been received from the following countries: Canada, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Slovakia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland and the USA. This note also includes the documents compiled for the same purpose and submitted to the fifty-second session of the Specialized Section. I. Documents submitted to the 52nd session of the Specialized Section A. UNECE Standard for Apples – List of Varieties At the last meeting the 51 st session of the Specialized Section GE.1 the delegation of the United Kingdom offered to coordinate efforts to simplify the list of apple varieties. The aim was to see what the result would be if we only include the most important varieties that are produced and traded. The list is designed to help distinguish apple varieties by colour groups, size and russeting it is not exhaustive, non-listed varieties can still be marketed. The idea should not be to list every variety grown in every country. The UK asked for views on what were considered to be the most important top thirty varieties. Eight countries sent their views, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, USA, Slovakia, Germany Finland and the Czech Republic. -

The Comparison of Sensory Quality and Processing Potential of ‘Topaz’ Apples Grown in Organic Orchards and Orchards Managed in Integrated Production System

Journal of Fruit and Ornamental Plant Research Vol. 20(2) 2012: 51-61 DOI: 10.2478/v10290-012-0015-7 THE COMPARISON OF SENSORY QUALITY AND PROCESSING POTENTIAL OF ‘TOPAZ’ APPLES GROWN IN ORGANIC ORCHARDS AND ORCHARDS MANAGED IN INTEGRATED PRODUCTION SYSTEM Dorota Konopacka 1, Urszula Kaczmarek1, Aneta Matulska1, Anna Wawrzyńczak1, Dorota Kruczyńska2 and Krzysztof P. Rutkowski1 1Department of Fruit Storage and Processing 2 Department of Pomology, Genetic Resources and Nursery Research Institute of Horticulture 96-100 Skierniewice, Konstytucji 3 Maja 1/3, POLAND e-mail: [email protected] (Received Novembr 22, 2012/Accepted December 14, 2012) ABSTRACT The aim of the study was to compare the sensory quality of scab resistant ‘Topaz’ apples grown in certified organic orchards (ECO) with those grown in orchards man- aged within integrated method (IP), and to determine their potential processing suit- ability. Fruits were harvested in five certificated IP and ECO orchards at the optimum ripeness stage and stored for two months in normal atmosphere at 1 ºC. Apple quality was assessed one day after cold storage and after 7 days of storage at the temperature 18 ºC to simulate shelf life. The results of taste and flavour sensory assessment did not explicitly demonstrate the effect of the orchard management system on the overall eating quality. Although the fruits from the organic orchards were perceived as less sweet and sourer, the management system did not influence the overall eating quality. There was no effect of the growing technology on quality traits connected with aroma and overall texture assessment. Regarding appearance evaluation, fruits from organic orchards were characterized by a higher variation in shape and size, and more fre- quently than in the case of IP apples had blemishes, scars and rust, which negatively affected their attractiveness. -

Seven-Year Orchard Performance of Eleven New Apple Cultivars from Holovousy in Comparison with Some Commonly Grown Ones

Seven-year orchard performance of eleven new apple cultivars from Holovousy in comparison with some commonly grown ones J. Blažek, J. Křelinová Research and Breeding Institute of Pomology, Holovousy, Czech Republic AbsTRACT: In an orchard trial that was established in the spring of 1999 on M 9 rootstock at the spacing of 4 × 1 m, eleven new apple cultivars bred in Holovousy (Angold, Julia, Nabella, Primadela, Produkta, Resista, Rubinstep, Rucla, Selena, Vysočina and Zuzana) were evaluated in comparison with three standard varieties (Gala, Golden Delicious and Jonagold) and another two with resistance to scab (Rosana and Topaz). In the first three years, the incidence of scab and mildew was evaluated under limited chemical protection. In 2000–2005 on each of 10 randomly selected trees of each cultivar, the time of flowering and optimum harvest ripening were recorded, flower set and fruit sets were rated, yield per tree and weight of 10 fruit samples were measured. Trunk diameter was measured between 2002 and 2005. The early summer apple Julia had the healthiest state and it was recommended for organic growing. Selena was the most precocious, the least vigorous and had the highest crop efficiency. The highest annual yields per tree were recorded with Produkta, but this cultivar had the highest proportion of trees with biennial bearing. Primadela achieved the high- est cumulative yields, whereas Angold brought the largest fruits on average. With the obtained results, the evaluated cultivars were characterised by some important features or recommendations for growers. Keywords: apples; cultivars; yields; fruit size; tree vigour; fruit set; time of flowering; time of harvest; yield efficiency; biennial bearing; scab; mildew More than 50 new apple cultivars have been mercial orchards of the Czech Republic. -

Using Whole-Genome SNP Data to Reconstruct a Large Multi-Generation

Muranty et al. BMC Plant Biology (2020) 20:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-2171-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Using whole-genome SNP data to reconstruct a large multi-generation pedigree in apple germplasm Hélène Muranty1*† , Caroline Denancé1†, Laurence Feugey1, Jean-Luc Crépin2, Yves Barbier2, Stefano Tartarini3, Matthew Ordidge4, Michela Troggio5, Marc Lateur6, Hilde Nybom7, Frantisek Paprstein8, François Laurens1 and Charles-Eric Durel1 Abstract Background: Apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.) is one of the most important fruit tree crops of temperate areas, with great economic and cultural value. Apple cultivars can be maintained for centuries in plant collections through grafting, and some are thought to date as far back as Roman times. Molecular markers provide a means to reconstruct pedigrees and thus shed light on the recent history of migration and trade of biological materials. The objective of the present study was to identify relationships within a set of over 1400 mostly old apple cultivars using whole-genome SNP data (~ 253 K SNPs) in order to reconstruct pedigrees. Results: Using simple exclusion tests, based on counting the number of Mendelian errors, more than one thousand parent-offspring relations and 295 complete parent-offspring families were identified. Additionally, a grandparent couple was identified for the missing parental side of 26 parent-offspring pairings. Among the 407 parent-offspring relations without a second identified parent, 327 could be oriented because one of the individuals was an offspring in a complete family or by using historical data on parentage or date of recording. Parents of emblematic cultivars such as ‘Ribston Pippin’, ‘White Transparent’ and ‘Braeburn’ were identified.