Some Expected Mechanical Characteristics of Lunar Dust: a Geological View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Identify Rocks and Minerals

How to Identify Rocks and Minerals fluorite calcite epidote quartz gypsum pyrite copper fluorite galena By Jan C. Rasmussen (Revised from a booklet by Susan Celestian) 2012 Donations for reproduction from: Freeport McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation Friends of the Arizona Mining & Mineral Museum Wickenburg Gem & Mineral Society www.janrasmussen.com ii NUMERICAL LIST OF ROCKS & MINERALS IN KIT See final pages of book for color photographs of rocks and minerals. MINERALS: IGNEOUS ROCKS: 1 Talc 2 Gypsum 50 Apache Tear 3 Calcite 51 Basalt 4 Fluorite 52 Pumice 5 Apatite* 53 Perlite 6 Orthoclase (feldspar group) 54 Obsidian 7 Quartz 55 Tuff 8 Topaz* 56 Rhyolite 9 Corundum* 57 Granite 10 Diamond* 11 Chrysocolla (blue) 12 Azurite (dark blue) METAMORPHIC ROCKS: 13 Quartz, var. chalcedony 14 Chalcopyrite (brassy) 60 Quartzite* 15 Barite 61 Schist 16 Galena (metallic) 62 Marble 17 Hematite 63 Slate* 18 Garnet 64 Gneiss 19 Magnetite 65 Metaconglomerate* 20 Serpentine 66 Phyllite 21 Malachite (green) (20) (Serpentinite)* 22 Muscovite (mica group) 23 Bornite (peacock tarnish) 24 Halite (table salt) SEDIMENTARY ROCKS: 25 Cuprite 26 Limonite (Goethite) 70 Sandstone 27 Pyrite (brassy) 71 Limestone 28 Peridot 72 Travertine (onyx) 29 Gold* 73 Conglomerate 30 Copper (refined) 74 Breccia 31 Glauberite pseudomorph 75 Shale 32 Sulfur 76 Silicified Wood 33 Quartz, var. rose (Quartz, var. chert) 34 Quartz, var. amethyst 77 Coal 35 Hornblende* 78 Diatomite 36 Tourmaline* 37 Graphite* 38 Sphalerite* *= not generally in kits. Minerals numbered 39 Biotite* 8-10, 25, 29, 35-40 are listed for information 40 Dolomite* only. www.janrasmussen.com iii ALPHABETICAL LIST OF ROCKS & MINERALS IN KIT See final pages of book for color photographs of rocks and minerals. -

Key to Rocks & Minerals Collections

STATE OF MICHIGAN MINERALS DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVISION A mineral is a rock substance occurring in nature that has a definite chemical composition, crystal form, and KEY TO ROCKS & MINERALS COLLECTIONS other distinct physical properties. A few of the minerals, such as gold and silver, occur as "free" elements, but by most minerals are chemical combinations of two or Harry O. Sorensen several elements just as plants and animals are Reprinted 1968 chemical combinations. Nearly all of the 90 or more Lansing, Michigan known elements are found in the earth's crust, but only 8 are present in proportions greater than one percent. In order of abundance the 8 most important elements Contents are: INTRODUCTION............................................................... 1 Percent composition Element Symbol MINERALS........................................................................ 1 of the earth’s crust ROCKS ............................................................................. 1 Oxygen O 46.46 IGNEOUS ROCKS ........................................................ 2 Silicon Si 27.61 SEDIMENTARY ROCKS............................................... 2 Aluminum Al 8.07 METAMORPHIC ROCKS.............................................. 2 Iron Fe 5.06 IDENTIFICATION ............................................................. 2 Calcium Ca 3.64 COLOR AND STREAK.................................................. 2 Sodium Na 2.75 LUSTER......................................................................... 2 Potassium -

"References" at End. 38- of 'Siliceous' by Nearly 60 Years

TERMINOLOGY OF H CHEMICAL SILICEOUS SEDIMEWS* W.A. Tarr "Chert. -- The origin of the word 'chert' has not been determined. The Oxford Dictionary suggests it was a local term that found its way into geological usage, 'Chirt' (now obsolete) appears to have been an early spelling of the word. In comparison with 'flint, ' chert' is a very recent word. 'Flint,' from very ancient times, was applied to the dark varieties of this siliceous material. Apparently, the lighter colored varities, now called 'chert,' were unrecognized as siliceous material; at any rate, no name describing the material has been found in the very early literature. The first specific use of the word 'chert' seems to have been in 1729 (i) when it was defined as a 'kind of flint, The French name for chert is com- monly given as silex corne (horn flint) or silex de la craie (flint of the chalk), but Cayeux states that the American term 'chert' corresponds to the French word silexite. He- uses chert to designate a related material occurring in siliceous beds (3). The German term for chert is Hornstein. 'Phtanite' (often misspelled Tptanitet) has been used as a synonym for chert. Cayeux uses the term synonymously as the equivalent for silexite, and 'hornstone' has also frequently been so used. So common was the use of the term 'hornstone' during the early part of the last century that there is little doubt that it was then the prevalent name for the material chert, as quotations given under the discussion of hornstone will show. But most common among the synonyms for 'chert' is 'flint,' and since 'flint' had other synonyms, 'chert' acquired many of them. -

About Our Mineral World

About Our Mineral World Compiled from series of Articles titled "TRIVIAL PURSUITS" from News Nuggets by Paul F. Hlava "The study of the natural sciences ought to expand the mind and enlarge the ability to grasp intellectual problems." Source?? "Mineral collecting can lead the interested and inquisitive person into the broader fields of geology and chemistry. This progression should be the proper outcome. Collecting for its own sake adds nothing to a person's understanding of the world about him. Learning to recognize minerals is only a beginning. The real satisfaction in mineralogy is in gaining knowledge of the ways in which minerals are formed in the earth, of the chemistry of the minerals and of the ways atoms are packed together to form crystals. Only by grouping minerals into definite categories is is possible to study, describe, and discuss them in a systematic and intelligent manner." Rock and Minerals, 1869, p. 260. Table of Contents: AGATE, JASPER, CHERT AND .............................................................................................................................2 GARNETS..................................................................................................................................................................2 GOLD.........................................................................................................................................................................3 "The Mystery of the Magnetic Dinosaur Bones" .......................................................................................................4 -

A Phase-Field Approach to Conchoidal Fracture

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) A phase-field approach to conchoidal fracture Carola Bilgen · Alena Kopanicˇakov´ a´ · Rolf Krause · Kerstin Weinberg ?? Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract Crack propagation involves the creation of new mussel shell like shape and faceted surfaces of fracture and internal surfaces of a priori unknown paths. A first chal- show that our approach can accurately capture the specific lenge for modeling and simulation of crack propagation is details of cracked surfaces, such as the rippled breakages of to identify the location of the crack initiation accurately, conchoidal fracture. Moreover, we show that using our ap- a second challenge is to follow the crack paths accurately. proach the arising systems can also be solved efficiently in Phase-field models address both challenges in an elegant parallel with excellent scaling behavior. way, as they are able to represent arbitrary crack paths by Keywords phase field, multigrid method, brittle fracture, means of a damage parameter. Moreover, they allow for the crack initiation, conchoidal fracture representation of complex crack patterns without changing the computational mesh via the damage parameter - which however comes at the cost of larger spatial systems to be 1 Introduction solved. Phase-field methods have already been proven to predict complex fracture patterns in two and three dimen- The prediction of crack nucleation and fragmentation pat- sional numerical simulations for brittle fracture. In this pa- tern is one of the main challenges in solid mechanics. Ev- per, we consider phase-field models and their numerical sim- ery crack in a solid forms a new surface of an a priori un- ulation for conchoidal fracture. -

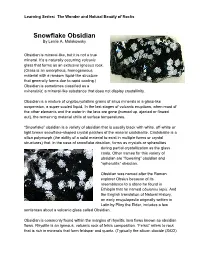

Mar- Snowflake Obsidian

Learning Series: The Wonder and Natural Beauty of Rocks Snowflake Obsidian By Leslie A. Malakowsky Obsidian is mineral-like, but it is not a true mineral. It’s a naturally occurring volcanic glass that forms as an extrusive igneous rock. (Glass is an amorphous, homogeneous material with a random liquid-like structure that generally forms due to rapid cooling.) Obsidian is sometimes classified as a mineraloid, a mineral-like substance that does not display crystallinity. Obsidian is a mixture of cryptocrystalline grains of silica minerals in a glass-like suspension, a super-cooled liquid. In the last stages of volcanic eruptions, when most of the other elements and the water in the lava are gone (burned up, ejected or flowed out), the remaining material chills at surface temperatures. “Snowflake” obsidian is a variety of obsidian that is usually black with white, off-white or light brown snowflake-shaped crystal patches of the mineral cristobalite. Cristobalite is a silica polymorph (the ability of a solid material to exist in multiple forms or crystal structures) that, in the case of snowflake obsidian, forms as crystals or spherulites during partial crystallization as the glass cools. Other names for this variety of obsidian are “flowering” obsidian and “spherulitic” obsidian. Obsidian was named after the Roman explorer Obsius because of its resemblance to a stone he found in Ethiopia that he named obsianus lapis. And the English translation of Natural History, an early encyclopedia originally written in Latin by Pliny the Elder, includes a few sentences about a volcanic glass called Obsidian. Obsidian is commonly found within the margins of rhyolitic lava flows known as obsidian flows. -

Lab 3 Class:Silicates

GLY 4310C LAB 3 CLASS:SILICATES Subclass:Tectosilicates Silica Group - Crystalline and Amorphous Mineral Name H G Color Cleavage, Luster Other Notes Streak Color Fracture, or Properties Parting QUARTZ, VAR. ROCK 7 2.7 clear/none conchoidal fracture vitreous transparent CRYSTAL QUARTZ, VAR. ROSE 7 2.7 pink/none subconchoidal fracture vitreous translucent QUARTZ, VAR. SMOKY 7 2.7 gray-brown/none even to subconchoidal vitreous translucent fracture QUARTZ, VAR. AMETHYST 7 2.7 lilac/none poor conchoidal vitreous transparent to parallel striations on fracture translucent crystal faces QUARTZ, VAR. CITRINE 7 2.7 golden brown/none even fracture vitreous translucent QUARTZ, VAR. MILKY 7 2.7 milky/none even to subconchoidal vitreous fracture QUARTZ, VAR. CHRYSOPRASE 7 2.7 green with blue even fracture dull translucent on thin streaks/none edges CRISTOBALITE 4.5 nd gray/white uneven fracture dull in obsidian OPAL 6.5 2.3 yellow-white/none conchoidal fracture resinous DIATOMACEOUS EARTH <1.0 <2.0 white/white uneven fracture dull absorbs liquid 1 GLY 4310C LAB 3 CLASS:SILICATES Subclass:Tectosilicates Silica - cryptocrystalline Mineral Name H G Color Cleavage, Luster Other Notes Streak Color Fracture, or Properties Parting QUARTZ, VAR. CHALCEDONY 7.0 2.7 white to gray-black conchoidal fracture waxy SW-green bands/none QUARTZ, VAR. JASPER 7.0 2.7 brick red, mustard,or conchoidal fracture greasy to dull black/none QUARTZ, VAR. FLINT 7.0 2.7 tan-gray to dark- conchoidal fracture dull LW-pale yellow gray/none QUARTZ, VAR. CHERT 7.0 2.9 milky to gray/none conchoidal fracture dull edges are very sharp QUARTZ, VAR. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

Correlation of the Mohs's Scale of Hardness with the Vickers' S Hardness Numbers

718 Correlation of the Mohs's scale of hardness with the Vickers' s hardness numbers. By E. WILFRED TAYLOR, C.B.E., F.R.M.S., F. Inst. P. Messrs. Cooke, Troughton & Simms, Ltd., York. [Read June 23, 1949.] INERALOGISTS have long been accustomed to describe hard- M ness with the aid of a scale devised by Friedrich Mohs, who lived from 1773 to 1839. The test is qualitative, each mineral in the scale being capable of scratching those that precede it, but the ten minerals have held their ground as a useful representative series with which it is now interesting to compare another method of estimating hard- ness. In the metallurgical world hardness is now usually expressed by means of the Vickers's hardness numbers or their equivalent, and the figures are derived from the size of the impression made by a diamond indenter in the form of a four-sided pyramid with the opposite faces worked to an included angle of 136 ~ More recently micro-hardness testers have been devised to enable minute impressions to be formed under light loads on small individual crystals of a metallic alloy, 1 and it occurred to the author to obtain hardness figures for the various types of optical glass by means of a scratch test with such an instrument. The intention was to draw a lightly loaded diamond across a polished glass surface and to measure the width of the resulting furrow. This method proved to be promising, but as an experiment a static indenter was also used, and it was dis- covered that glass was sufficiently plastic to take good impressions, so long as the load did not exceed 50 grams or thereabouts. -

Procurement and Use of Chert from Localized Sources in Trinidad

Journal of Caribbean Archaeology Copyright 2015 ISBN 1524-4776 Procurement and Use of Chert from Localized Sources in Trinidad Jack H. Ray Center for Archaeological Research Missouri State University 901 South National Avenue Springfield, Missouri 65897 [email protected] Relatively little is known about the procurement and use of chert as a lithic resource by prehistoric Amerindians in Trinidad. Although not common, chert artifacts are present on both Archaic and Ceramic Age sites throughout much of Trinidad. Recent research in the Central Range has located and documented two previously undocumented localized sources where chert is readily available. Other previously reported localized sources of chert in the Northern, Central, and Southern Ranges were also visited. The chert at each source is described and characterized in terms of suitability for working. Analysis of chert artifacts from ten sites spread across Trinidad, as well as the description of chert artifacts from several other sites, revealed that Malchan Hill, located in the Central Range, appears to have been a primary source for many of the chert artifacts found in Trinidad. The technology that was used to produce the majority of chert artifacts is based on bipolar percussion for the production of simple flake blanks. These sharp unmodified flake blanks appear to have been used for various cutting and scraping purposes in Archaic times, whereas many of the flake blanks were smashed into angular wedge-shaped pieces to be used as teeth in grater boards for the processing of plant foods, especially cassava, in Ceramic times. Relativamente poco se sabe acerca de la adquisición y el uso del sílex como recurso lítico por los amerindios prehistóricos en Trinidad. -

Perspectives of Micro and Nanofabrication of Carbon for Electrochemical and Microfluidic Applications

Chapter 5 Perspectives of Micro and Nanofabrication of Carbon for Electrochemical and Microfluidic Applications R. Martinez-Duarte, G. Turon Teixidor, P.P. Mukherjee, Q. Kang, and M.J. Madou Abstract This chapter focuses on glass-like carbons, their method of micro and nanofabrication and their electrochemical and microfluidic applications. At first, the general properties of this material are exposed, followed by its advantages over other forms of carbon and over other materials. After an overview of the carbonization process of organic polymers we delve into the history of glass-like carbon. The bulk of the chapter deals with different fabrication tools and techniques to pattern poly- mers. It is shown that when it comes to carbon patterning, it is significantly easier and more convenient to shape an organic polymer and carbonize it than to machine carbon directly. Therefore the quality, dimensions and complexity of the final carbon part greatly depend on the polymer structure acting as a precursor. Current fabrica- tion technologies allow for the patterning of polymers in a wide range of dimensions and with a great variety of tools. Even though several fabrication techniques could be employed such as casting, stamping or even Computer Numerical Controlled (CNC) machining, the focus of this chapter is on photolithography, given its precise control over the fabrication process and its reproducibility. Next Generation Lithography (NGL) tools are also covered as a viable way to achieve nanometer-sized carbon features. These tools include electron beam (e-beam), Focused-ion beam (FIB), Nano Imprint Lithography (NIL) and Step-and-Flash Imprint Lithography (SFIL). At last, the use of glass-like carbon in three applications, related to microfluidics and electrochemistry, is discussed: Dielectrophoresis, Electrochemical sensors, and Fuel Cells. -

Methods Used to Identifying Minerals

METHODS USED TO IDENTIFYING MINERALS More than 4,000 minerals are known to man, and they are identified by their physical and chemical properties. The physical properties of minerals are determined by the atomic structure and crystal chemistry of the minerals. The most common physical properties are crystal form, color, hardness, cleavage, and specific gravity. CRYSTALS One of the best ways to identify a mineral is by examining its crystal form (external shape). A crystal is defined as a homogenous solid possessing a three-dimensional internal order defined by the lattice structure. Crystals developed under favorable conditions often exhibit characteristic geometric forms (which are outward expressions of the internal arrangements of atoms), crystal class, and cleavage. Large, well- developed crystals are not common because of unfavorable growth conditions, but small crystals recognizable with a hand lens or microscope are common. Minerals that show no external crystal form but possess an internal crystalline structure are said to be massive. A few minerals, such as limonite and opal, have no orderly arrangement of atoms and are said to be amorphous. Crystals are divided into six major classes based on their geometric form: isometric, tetragonal, hexagonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, and triclinic. The hexagonal system also has a rhombohedral subdivision, which applies mainly to carbonates. CLEAVAGE AND FRACTURE After minerals are formed, they have a tendency to split or break along definite planes of weakness. This property is called cleavage. These planes of weakness are closely related to the internal structure of the mineral, and are usually, but not always, parallel to crystal faces or possible crystal faces.