About Our Mineral World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Identify Rocks and Minerals

How to Identify Rocks and Minerals fluorite calcite epidote quartz gypsum pyrite copper fluorite galena By Jan C. Rasmussen (Revised from a booklet by Susan Celestian) 2012 Donations for reproduction from: Freeport McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation Friends of the Arizona Mining & Mineral Museum Wickenburg Gem & Mineral Society www.janrasmussen.com ii NUMERICAL LIST OF ROCKS & MINERALS IN KIT See final pages of book for color photographs of rocks and minerals. MINERALS: IGNEOUS ROCKS: 1 Talc 2 Gypsum 50 Apache Tear 3 Calcite 51 Basalt 4 Fluorite 52 Pumice 5 Apatite* 53 Perlite 6 Orthoclase (feldspar group) 54 Obsidian 7 Quartz 55 Tuff 8 Topaz* 56 Rhyolite 9 Corundum* 57 Granite 10 Diamond* 11 Chrysocolla (blue) 12 Azurite (dark blue) METAMORPHIC ROCKS: 13 Quartz, var. chalcedony 14 Chalcopyrite (brassy) 60 Quartzite* 15 Barite 61 Schist 16 Galena (metallic) 62 Marble 17 Hematite 63 Slate* 18 Garnet 64 Gneiss 19 Magnetite 65 Metaconglomerate* 20 Serpentine 66 Phyllite 21 Malachite (green) (20) (Serpentinite)* 22 Muscovite (mica group) 23 Bornite (peacock tarnish) 24 Halite (table salt) SEDIMENTARY ROCKS: 25 Cuprite 26 Limonite (Goethite) 70 Sandstone 27 Pyrite (brassy) 71 Limestone 28 Peridot 72 Travertine (onyx) 29 Gold* 73 Conglomerate 30 Copper (refined) 74 Breccia 31 Glauberite pseudomorph 75 Shale 32 Sulfur 76 Silicified Wood 33 Quartz, var. rose (Quartz, var. chert) 34 Quartz, var. amethyst 77 Coal 35 Hornblende* 78 Diatomite 36 Tourmaline* 37 Graphite* 38 Sphalerite* *= not generally in kits. Minerals numbered 39 Biotite* 8-10, 25, 29, 35-40 are listed for information 40 Dolomite* only. www.janrasmussen.com iii ALPHABETICAL LIST OF ROCKS & MINERALS IN KIT See final pages of book for color photographs of rocks and minerals. -

Ajoite: New Data

American Mineralogist, Volume 66, pages 201-203, 1981 Ajoite: new data GEORGE Y. CHAO Department of Geology, Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario Kl S 5B6, Canada Abstract New data show that ajoite is triclinic, PI or pI, a ==13.637, b ==14.507, c ==13.620A, a == 107.16, f3 = 105.45, y = 110.57°; Z ==3. The mineral is biaxial positive, 2V ==80°, a ==1.550, f3 = 1.583, y = 1.641 (in Na light); pleochroic: X = very light bluish green, Y -- Z ==brilliant bluish green. {010} cleavage is perfect. The orientation of the principal vibration directions is defined by the spherical coordinates X(26.5°, 80°), Y(118°, 79°), Z(-104.5°, 15°). The ex- tinction angle c: Z' on (0 I0) is 150. Electron microprobe and chemical analyses gave Si02 41.2, Al203 3.81, CuO 42.2, MnO 0.02, FeO 0.11, CaO 0.04, Na20 0.84, K20 2.50, H20 (TGA to 1000°C) 8.35, sum 99.07 wt.%. The analysis corresponds to (Ko.70NaO.36Cao.Ol)(CUt,.97 Feo.o2)Alo.98Si9.oo024(OH)6'3.09H20 or ideally, (K,Na)Cu7AISi9024(OH)6' 3H20. TGA showed a two-stage dehydration; 50% of the total water was released between 70° and 425°C and the rest between 4250 and 800°C. Half of the water is zeolitic in nature. Introduction are always present. The termination on c may be ei- Ajoite, first described by Schaller and Vlisidis ther {001} or {203} or both. (1958) from Ajo, Pima County, Arizona, was thought to be monoclinic on the basis of optical studies. -

Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz

Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz September 10 – 13, 2005 Golden, Colorado Sponsored by Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter; Colorado School of Mines Geology Museum; and U.S. Geological Survey 2 Cover Photos {top left} Fortification agate, Hinsdale County, Colorado, collection of the Geology Museum, Colorado School of Mines. Coloration of alternating concentric bands is due to infiltration of Fe with groundwater into the porous chalcedony layers, leaving the impermeable chalcedony bands uncolored (white): ground water was introduced via the symmetric fractures, evidenced by darker brown hues along the orthogonal lines. Specimen about 4 inches across; photo Dan Kile. {lower left} Photomicrograph showing, in crossed-polarized light, a rhyolite thunder egg shell (lower left) a fibrous phase of silica, opal-CTLS (appearing as a layer of tan fibers bordering the rhyolite cavity wall), and spherulitic and radiating fibrous forms of chalcedony. Field of view approximately 4.8 mm high; photo Dan Kile. {center right} Photomicrograph of the same field of view, but with a 1 λ (first-order red) waveplate inserted to illustrate the length-fast nature of the chalcedony (yellow-orange) and the length-slow character of the opal CTLS (blue). Field of view about 4.8 mm high; photo Dan Kile. Copyright of articles and photographs is retained by authors and Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter; reproduction by electronic or other means without permission is prohibited 3 Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz Program and Abstracts September 10 – 13, 2005 Editors Daniel Kile Thomas Michalski Peter Modreski Held at Green Center, Colorado School of Mines Golden, Colorado Sponsored by Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter Colorado School of Mines Geology Museum U.S. -

Key to Rocks & Minerals Collections

STATE OF MICHIGAN MINERALS DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVISION A mineral is a rock substance occurring in nature that has a definite chemical composition, crystal form, and KEY TO ROCKS & MINERALS COLLECTIONS other distinct physical properties. A few of the minerals, such as gold and silver, occur as "free" elements, but by most minerals are chemical combinations of two or Harry O. Sorensen several elements just as plants and animals are Reprinted 1968 chemical combinations. Nearly all of the 90 or more Lansing, Michigan known elements are found in the earth's crust, but only 8 are present in proportions greater than one percent. In order of abundance the 8 most important elements Contents are: INTRODUCTION............................................................... 1 Percent composition Element Symbol MINERALS........................................................................ 1 of the earth’s crust ROCKS ............................................................................. 1 Oxygen O 46.46 IGNEOUS ROCKS ........................................................ 2 Silicon Si 27.61 SEDIMENTARY ROCKS............................................... 2 Aluminum Al 8.07 METAMORPHIC ROCKS.............................................. 2 Iron Fe 5.06 IDENTIFICATION ............................................................. 2 Calcium Ca 3.64 COLOR AND STREAK.................................................. 2 Sodium Na 2.75 LUSTER......................................................................... 2 Potassium -

Wickenburgite Pb3caal2si10o27² 3H2O

Wickenburgite Pb3CaAl2Si10O27 ² 3H2O c 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: Hexagonal. Point Group: 6=m 2=m 2=m: Tabular holohedral crystals, dominated by 0001 and 1011 , to 1.5 mm. As spongy aggregates of small, highly perfect f g f g individuals; as subparallel aggregates or rosettes; granular. Physical Properties: Cleavage: 0001 , indistinct. Tenacity: Brittle but tough. Hardness = 5 D(meas.) = 3.85 D(cfalc.) g= 3.88 Fluoresces dull orange under SW UV. Optical Properties: Transparent to translucent. Color: Colorless to white; rarely salmon-pink. Luster: Vitreous. Optical Class: Uniaxial ({). Dispersion: r < v; moderate. ! = 1.692 ² = 1.648 Cell Data: Space Group: P 63=mmc: a = 8.53 c = 20.16 Z = 2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Near Wickenburg, Arizona, USA. 10.1 (100), 3.26 (80), 3.93 (60), 3.36 (40), 2.639 (40), 5.96 (30), 5.04 (30) Chemistry: (1) (2) SiO2 42.1 40.53 Al2O3 7.6 6.88 PbO 44.0 45.17 CaO 3.80 3.78 H2O 3.77 3.64 Total 101.27 100.00 (1) Near Wickenburg, Arizona, USA. (2) Pb3CaAl2Si10O24(OH)6: [needsnew??formula] Occurrence: In oxidized hydrothermal veins, carrying galena and sphalerite, in quartz and °uorite gangue (near Wickenburg, Arizona, USA). Association: Phoenicochroite, mimetite, cerussite, willemite, crocoite, duftite, hemihedrite, alamosite, melanotekite, luddenite, ajoite, shattuckite, vauquelinite, descloizite, laumontite. Distribution: In the USA, in Arizona, at several localities south of Wickenburg, Maricopa Co., including the Potter-Cramer property, Belmont Mountains, and the Moon Anchor mine; on dumps at a Pb-Ag-Cu prospect in the Artillery Peaks area, Mohave Co.; and in the Dives (Padre Kino) mine, Silver district, La Paz Co. -

"References" at End. 38- of 'Siliceous' by Nearly 60 Years

TERMINOLOGY OF H CHEMICAL SILICEOUS SEDIMEWS* W.A. Tarr "Chert. -- The origin of the word 'chert' has not been determined. The Oxford Dictionary suggests it was a local term that found its way into geological usage, 'Chirt' (now obsolete) appears to have been an early spelling of the word. In comparison with 'flint, ' chert' is a very recent word. 'Flint,' from very ancient times, was applied to the dark varieties of this siliceous material. Apparently, the lighter colored varities, now called 'chert,' were unrecognized as siliceous material; at any rate, no name describing the material has been found in the very early literature. The first specific use of the word 'chert' seems to have been in 1729 (i) when it was defined as a 'kind of flint, The French name for chert is com- monly given as silex corne (horn flint) or silex de la craie (flint of the chalk), but Cayeux states that the American term 'chert' corresponds to the French word silexite. He- uses chert to designate a related material occurring in siliceous beds (3). The German term for chert is Hornstein. 'Phtanite' (often misspelled Tptanitet) has been used as a synonym for chert. Cayeux uses the term synonymously as the equivalent for silexite, and 'hornstone' has also frequently been so used. So common was the use of the term 'hornstone' during the early part of the last century that there is little doubt that it was then the prevalent name for the material chert, as quotations given under the discussion of hornstone will show. But most common among the synonyms for 'chert' is 'flint,' and since 'flint' had other synonyms, 'chert' acquired many of them. -

A Phase-Field Approach to Conchoidal Fracture

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) A phase-field approach to conchoidal fracture Carola Bilgen · Alena Kopanicˇakov´ a´ · Rolf Krause · Kerstin Weinberg ?? Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract Crack propagation involves the creation of new mussel shell like shape and faceted surfaces of fracture and internal surfaces of a priori unknown paths. A first chal- show that our approach can accurately capture the specific lenge for modeling and simulation of crack propagation is details of cracked surfaces, such as the rippled breakages of to identify the location of the crack initiation accurately, conchoidal fracture. Moreover, we show that using our ap- a second challenge is to follow the crack paths accurately. proach the arising systems can also be solved efficiently in Phase-field models address both challenges in an elegant parallel with excellent scaling behavior. way, as they are able to represent arbitrary crack paths by Keywords phase field, multigrid method, brittle fracture, means of a damage parameter. Moreover, they allow for the crack initiation, conchoidal fracture representation of complex crack patterns without changing the computational mesh via the damage parameter - which however comes at the cost of larger spatial systems to be 1 Introduction solved. Phase-field methods have already been proven to predict complex fracture patterns in two and three dimen- The prediction of crack nucleation and fragmentation pat- sional numerical simulations for brittle fracture. In this pa- tern is one of the main challenges in solid mechanics. Ev- per, we consider phase-field models and their numerical sim- ery crack in a solid forms a new surface of an a priori un- ulation for conchoidal fracture. -

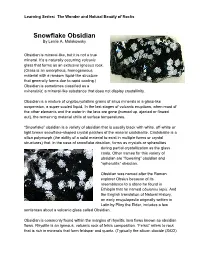

Mar- Snowflake Obsidian

Learning Series: The Wonder and Natural Beauty of Rocks Snowflake Obsidian By Leslie A. Malakowsky Obsidian is mineral-like, but it is not a true mineral. It’s a naturally occurring volcanic glass that forms as an extrusive igneous rock. (Glass is an amorphous, homogeneous material with a random liquid-like structure that generally forms due to rapid cooling.) Obsidian is sometimes classified as a mineraloid, a mineral-like substance that does not display crystallinity. Obsidian is a mixture of cryptocrystalline grains of silica minerals in a glass-like suspension, a super-cooled liquid. In the last stages of volcanic eruptions, when most of the other elements and the water in the lava are gone (burned up, ejected or flowed out), the remaining material chills at surface temperatures. “Snowflake” obsidian is a variety of obsidian that is usually black with white, off-white or light brown snowflake-shaped crystal patches of the mineral cristobalite. Cristobalite is a silica polymorph (the ability of a solid material to exist in multiple forms or crystal structures) that, in the case of snowflake obsidian, forms as crystals or spherulites during partial crystallization as the glass cools. Other names for this variety of obsidian are “flowering” obsidian and “spherulitic” obsidian. Obsidian was named after the Roman explorer Obsius because of its resemblance to a stone he found in Ethiopia that he named obsianus lapis. And the English translation of Natural History, an early encyclopedia originally written in Latin by Pliny the Elder, includes a few sentences about a volcanic glass called Obsidian. Obsidian is commonly found within the margins of rhyolitic lava flows known as obsidian flows. -

Nomenclature of the Garnet Supergroup

American Mineralogist, Volume 98, pages 785–811, 2013 IMA REPORT Nomenclature of the garnet supergroup EDWARD S. GREW,1,* ANDREW J. LOCOCK,2 STUART J. MILLS,3,† IRINA O. GALUSKINA,4 EVGENY V. GALUSKIN,4 AND ULF HÅLENIUS5 1School of Earth and Climate Sciences, University of Maine, Orono, Maine 04469, U.S.A. 2Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E3, Canada 3Geosciences, Museum Victoria, GPO Box 666, Melbourne 3001, Victoria, Australia 4Faculty of Earth Sciences, Department of Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Petrography, University of Silesia, Będzińska 60, 41-200 Sosnowiec, Poland 5Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Mineralogy, P.O. Box 50 007, 104 05 Stockholm, Sweden ABSTRACT The garnet supergroup includes all minerals isostructural with garnet regardless of what elements occupy the four atomic sites, i.e., the supergroup includes several chemical classes. There are pres- ently 32 approved species, with an additional 5 possible species needing further study to be approved. The general formula for the garnet supergroup minerals is {X3}[Y2](Z3)ϕ12, where X, Y, and Z refer to dodecahedral, octahedral, and tetrahedral sites, respectively, and ϕ is O, OH, or F. Most garnets are cubic, space group Ia3d (no. 230), but two OH-bearing species (henritermierite and holtstamite) have tetragonal symmetry, space group, I41/acd (no. 142), and their X, Z, and ϕ sites are split into more symmetrically unique atomic positions. Total charge at the Z site and symmetry are criteria for distinguishing groups, whereas the dominant-constituent and dominant-valency rules are critical in identifying species. Twenty-nine species belong to one of five groups: the tetragonal henritermierite group and the isometric bitikleite, schorlomite, garnet, and berzeliite groups with a total charge at Z of 8 (silicate), 9 (oxide), 10 (silicate), 12 (silicate), and 15 (vanadate, arsenate), respectively. -

Garnets from the Camafuca-Camazambo Kimberlite (Angola)

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2006) 78(2): 309-315 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) ISSN 0001-3765 www.scielo.br/aabc Garnets from the Camafuca-Camazambo kimberlite (Angola) EUGÉNIO A. CORREIA and FERNANDO A.T.P. LAIGINHAS Departamento de Geologia, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto Praça de Gomes Teixeira, 4050 Porto, Portugal Manuscript received on November 17, 2004; accepted for publication on June 13, 2005; presented by ALCIDES N. SIAL ABSTRACT This work presents a geochemical study of a set of garnets, selected by their colors, from the Camafuca- Camazambo kimberlite, located on northeast Angola. Mantle-derived garnets were classified according to the scheme proposed by Grütter et al. (2004) and belong to the G1, G4, G9 and G10 groups. Both sub-calcic (G10) and Ca-saturated (G9) garnets, typical, respectively, of harzburgites and lherzolites, were identified. The solubility limit of knorringite molecule in G10D garnets suggests they have crystallized at a minimum pressure of about 40 to 45 kbar (4– 4.5 GPa). The occurrence of diamond stability field garnets (G10D) is a clear indicator of the potential of this kimberlite for diamond. The chemistry of the garnets suggests that the source for the kimberlite was a lherzolite that has suffered a partial melting that formed basaltic magma, leaving a harzburgite as a residue. Key words: kimberlite, diamond, garnet, lherzolite, harzburgite. INTRODUCTION GEOCHEMICAL STUDY OF GARNETS The Camafuca-Camazambo kimberlite belongs to The geochemical study of mantle-derived garnets a kimberlite province comprising over a dozen of occurring in kimberlites progressed remarkably in primary occurrences of diamond, located along- recent years, as their chemistry is not only a possible side the homonymous brook which is a tributary of indicator of the presence of diamonds in their host the Chicapa river, in the proximity of the Calonda rock but also their abundance is a likely indicator of village, northeast Angola (Fig. -

Vibrational Spectroscopic Study of the Copper Silicate Mineral Ajoite (K, Na

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Frost, Ray& Xi, Yunfei (2012) Vibrational spectroscopic study of the copper silicate mineral ajoite (K,Na)Cu7AlSi9O24(OH)6.3H2O. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1018, pp. 72-77. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/50677/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] License: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2011.10.056 1 Vibrational spectroscopic study of the copper silicate mineral ajoite 2 (K,Na)Cu7AlSi9O24(OH)6·3H2O 3 Ray L. -

Synchrotron X-Ray Diffraction Study of the Structure of Shafranovskite, K2na3(Mn,Fe,Na)

American Mineralogist, Volume 89, pages 1816–1821, 2004 Synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of the structure of shafranovskite, ⋅ K2Na3(Mn,Fe,Na)4 [Si9(O,OH)27](OH)2 nH2O, a rare manganese phyllosilicate from the Kola peninsula, Russia SERGEY V. K RIVOVICHEV,1,2,* VIKTOR N. YAKOVENCHUK,3 THOMAS ARMBRUSTER,4 YAKOV A. PAKHOMOVSKY,3 HANS-PETER WEBER,5,6 AND WULF DEPMEIER2 1Department of Crystallography, Faculty of Geology, St. Petersburg State University, University Embankment 7/9 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia 2Institut für Geowissenschaften, Kiel Universität, Olshausenstrasse 40, 24118 Kiel, Germany 3Geological Institute, Kola Science Center, Russian Academy of Sciences, Apatity 184200, Russia 4Laboratorium für chemische and mineralogische Kristallographie, Universität Bern, Freiestrasse 3, CH-3102 Bern, Switzerland 5European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, BP 220, 38043 Grenoble, France 6Laboratoire de Cristallographie, University of Lausanne, BSP-Dorigny, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland ABSTRACT ⋅ ∼ The structure of shafranovskite, ideally K2Na3(Mn,Fe,Na)4[Si9(O,OH)27](OH)2 nH2O (n 2.33), a K-Na-manganese hydrous silicate from Kola peninsula, Russia, was studied using synchrotron X-ray radiation and a MAR345 image-plate detector at the Swiss-Norwegian beamline of the European Syn- chrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France). The structure [trigonal, space group P31c, a = 14.519(3), c = 21.062(6) Å, V = 3844.9(14) Å3] was solved by direct methods and partially refi ned to ≥ σ R1 = 0.085 (wR2 = 0.238) on the basis of 2243 unique observed refl ections (|Fo| 4 F). Shafranovskite is a 2:1 hydrous phyllosilicate. Sheets of Mn and Na octahedra (O sheets) are sandwiched between two silicate tetrahedral sheets (T1 and T2).