Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concrete Prehistories: the Making of Megalithic Modernism 1901-1939

Concrete Prehistories: The Making of Megalithic Modernism Abstract After water, concrete is the most consumed substance on earth. Every year enough cement is produced to manufacture around six billion cubic metres of concrete1. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern prehistories. We present an archaeology of concrete in the prehistoric landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury, where concrete is a major component of megalithic sites restored between 1901 and 1964. We explore how concreting changed between 1901 and the Second World War, and the implications of this for constructions of prehistory. We discuss the role of concrete in debates surrounding restoration, analyze the semiotics of concrete equivalents for the megaliths, and investigate the significance of concreting to interpretations of prehistoric building. A technology that mixes ancient and modern, concrete helped build the modern archaeological imagination. Concrete is the substance of the modern –”Talking about concrete means talking about modernity” (Forty 2012:14). It is the material most closely associated with the origins and development of modern architecture, but in the modern era, concrete has also been widely deployed in the preservation and display of heritage. In fact its ubiquity means that concrete can justifiably claim to be the single most dominant substance of heritage conservation practice between 1900 and 1945. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern pasts, and in particular, modern prehistories. As the pre-eminent marker of modernity, concrete was used to separate ancient from modern, but efforts to preserve and display prehistoric megaliths saw concrete and megaliths become entangled. -

The Lives of Prehistoric Monuments in Iron Age, Roman, and Medieval Europe by Marta Díaz-Guardamino, Leonardo García Sanjuán and David Wheatley (Eds)

The Prehistoric Society Book Reviews THE LIVES OF PREHISTORIC MONUMENTS IN IRON AGE, ROMAN, AND MEDIEVAL EUROPE BY MARTA DÍAZ-GUARDAMINO, LEONARDO GARCÍA SANJUÁN AND DAVID WHEATLEY (EDS) Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2015. 356pp, 50 figs, 32 B/W plates, 6 tables. ISBN 978-0-19-872460-5, hb, £85 This handsome book is the outcome of a session at the 2013 European Association of Archaeologists in Pilsen, organised by the editors on the cultural biographies of monuments. It is divided into three sections, with the main part comprising 13 detailed case-studies, framed on either side by shorter introduction and discussion pieces. There is variety in the chronologies, subject matters and geographical scopes addressed; in short there is something for almost everyone! In their Introduction, the editors advocate that archaeologists require a more reflexive conceptual toolkit to deal with the complex issues of monument continuity, transformation, re-use and abandonment, and the significance of the speed and the timing of changes. They also critique the loaded term ‘afterlife’ as this separates the unfolding biography of a monument, and unwittingly relegates later activities to lesser importance than its original function. In the following chapter, Joyce Salisbury explores how the veneration of natural places in the landscape, such as caves and mountains, was shifted to man-made monumental features over time. The bulk of the book focuses on the specific case-studies which span Denmark in the north to Tunisia in the south and from Ireland in the west to Serbia and Crete in the east. In Chapter 3, Steen Hvass’s account of the history of research at the monument complex of King’s Jelling in Denmark is fascinating, but a little heavy on stratigraphic narrative, and light on theory and discussion. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Stonehenge and Avebury WHS Management Plan 2015 Summary

Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site Vision The Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site is universally important for its unique and dense concentration of outstanding prehistoric monuments and sites which together form a landscape without parallel. We will work together to care for and safeguard this special area and provide a tranquil, rural and ecologically diverse setting for it and its archaeology. This will allow present and future generations to explore and enjoy the monuments and their landscape setting more fully. We will also ensure that the special qualities of the World Heritage Site are presented, interpreted and enhanced where appropriate, so that visitors, the local community and the whole world can better understand and value the extraordinary achievements © K020791 Historic England © K020791 Historic of the prehistoric people who left us this rich legacy. Avebury Stone Circle We will realise the cultural, scientific and educational potential of the World Heritage Site as well as its social and economic benefits for the community. © N060499 Historic England © N060499 Historic Stonehenge in summer 2 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 World Heritage Sites © K930754 Historic England © K930754 Historic Arable farming in the WHS below the Ridgeway, Avebury The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site is internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments. Stonehenge is the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world, while Avebury is Stonehenge and Avebury were inscribed as a single World Heritage Site in 1986 for their outstanding prehistoric monuments the largest. -

2260 B.C. 2850 B.C. 5940 ± 150 Gsy-36 A. Roucadour a 3990 B.C

[RADIOCARBON, VOL. 8, 1966, P. 128-141] GIF-SUR-YVETTE NATURAL RADIOCARBON MEASUREMENTS I J. COURSAGET and J. LE RUN Radiocarbon Laboratory, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Gif-sur-Yvette (Essonne), France The following list shows the age measurements carried out from 1958 to March 1963 at the Radiocarbon Laboratory at Gif-sur-Yvette. This laboratory has been replaced by a new one whose first measure- ments are also given in this volume. It was equipped with 2 proportional counters similar to those used in Saclay laboratory and operating with 1 atm of pure C02. These counters were shielded by 15 cm lead, 5 cm iron and 1.5 cm of mercury. Data have been calculated on the basis of a C14 half-life of 5570 yr, in agreement with the decision of the Fifth Radiocarbon Dating Confer- ence. As a modern carbon standard, wood taken from old furniture was used. This standard was found equivalent to 950 of the activity of the NBS oxalic acid, if a 2% Suess-effect is adopted for this wood. SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS I. ARCHAEOLOGIC SAMPLES A. Southern France Perte du Cros series, Saillac, Lot Burnt wheat from Hearth III at entrance of cave of Perte du Cros, Saillac, Lot (44° 20' N Lat, 1° 37' E Long). Coll. 1957 by A. Calan; subm. by J. Arnal, Treviers, Herault. 4210 ± 150 Gsy-35 A. Perte du Cros 2260 B.C. 4800 ± 130 Gsy-35 B. Perte du Cros 2850 B.C. General Comment: associated with Middle Neolithic of Chasseen type un- (Galan 1958) ; Gsy-35 A may be contaminated. -

Stonehenge and Ancient Astronomy Tonehenge Is One of the Most Impressive and Best Known Prehistoric Stone Monuments in the World

Stonehenge and Ancient Astronomy tonehenge is one of the most impressive and best known prehistoric stone monuments in the world. Ever since antiquarians’ accounts began to bring the site to wider attention inS the 17th century, there has been endless speculation about its likely purpose and meaning, and a recurring theme has been its possible connections with astronomy and the skies. was it a Neolithic calendar? A solar temple? A lunar observatory? A calculating device for predicting eclipses? Or perhaps a combination of more than one of these? In recent years Stonehenge has become the very icon of ancient astronomy, featuring in nearly every discussion on the subject. And yet there are those who persist in believing that it actually had little or no connection with astronomy at all. A more informed picture has been obtained in recent years by combining evidence from archaeology and astronomy within the new interdiscipline of archaeoastronomy – the study of beliefs and practices concerning the sky in the past and the uses to which people’s knowledge of the skies were put. This leaflet attempts to summarize the evidence that the Stonehenge monument was constructed by communities with a clear interest in the sky above them. Photograph: Stonehenge in the snow. (Skyscan/english heritagE) This leaflet is one of a series produced by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). An electronic version is available for download at www.ras.org.uk. It has been written by the following members of the RAS Astronomical Heritage Committee: Clive Ruggles, Bill Burton, David Hughes, Andrew lawson and Derek McNally. -

Megaliths, Monuments & Tombs of Wessex & Brittany

From Stonehenge to Carnac: Megaliths, Monuments & Tombs of Wessex & Brittany Menhhir du Champs Dolent SLM (1).JPG May 25 - June 5, 2021 (12 days | 14 guests) with prehistorian Paul G. Bahn © Jane Waldbaum ©Vigneron ©AAlphabet © DChandra © DBates Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur “The special tour of Stonehenge was a highlight, as well as visiting the best of the best of prehistoric sites with Archaeological Institute an immensely knowledgeable guide like Paul Bahn.” of America - Grant, Ontario Lecturer xplore the extraordinary prehistoric sites of Wessex, England, & Host and Brittany, France. Amidst beautiful landscapes see world renowned, as well as lesser known, Neolithic and Bronze Age Emegaliths and monuments such as enigmatic rings of giant standing stones and remarkable chambered tombs. Dr. Paul G. Bahn is a leading archaeological writer, translator, and broadcaster in the Highlights: field of archaeology. He is a Contributing Editor of the AIA’s Archaeology magazine, • Stonehenge, the world’s most famous megalithic site, which is a and has written extensively on prehistoric UNESCO World Heritage site together with Avebury, a unique art, including the books Images of the Ice Neolithic henge that includes Europe’s largest prehistoric stone circle. Age, The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art, and Cave Art: A Guide to • Enigmatic chambered tombs such as West Kennet Long Barrow. the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe. Dr. • Carnac, with more than 3,000 prehistoric standing stones, the Bahn has also authored and/or edited many world’s largest collection of megalithic monuments. books on more general archaeological subjects, bringing a broad perspective to • The uninhabited island of Gavrinis, with a magnificent passage tomb understanding the sites and museums that is lined with elaborately engraved, vertical stones. -

2021-01-15 - Lecture 03

2021-01-15 - Lecture 03 1.3 Megaliths and Stone Circles; Building as Memory 1) Architecture as Second Nature begins as creating mere dwelling… a place of protection from the forces of nature. Soon, building begins to take on more significance as it embodies symbolic and ritualistic meaning, becomes a place of reverence, and becomes a place of memorialization of the dead and the marking of time of human memory… 2) Vocabulary: • cairn — burial mound of stones (may have earth on top of stones). British Isles term. • dolmen — two megaliths (or more) standing upright and capped by a trabeated megalith • menhirs — raised stones, similar to a stele or gravestone but may have more meaning due to formal attributes of their arrangement • orthostats — vertical megaliths revetting the lower cella (chamber) of a proto-temple • poché — in an architectural diagram, the poché is the representation of material that forms space within a building. This is it’s first meaning. There are more. • revetment — sloping or battered walls reinforced with stronger material, usually stone • trabeation — a word that describes a post and lintel structural configuration • trilithon — a dolmen-type arrangement of three megaliths • tumulus — burial mound of earth, not necessarily including stone (but may) • vernacular — a building tradition based on tradition rather than formal education. May be based more on local programmatic needs (bank barns, tobacco barns, dogtrot houses), availability of materials, and traditions of building rather than any formal ideas. Vernacular architecture rarely has a known architect. 3) Examples of stone arrangements for memory and for celestial understanding: • Carnac, Brittany, France. Fields of menhirs — 4000 - 2500 BCE. -

June 2016 in France: Chasing the Neolithic - Elly’S Notes

June 2016 in France: chasing the Neolithic - Elly’s notes I had a conference in the middle of June in Caen, Normandy, and another the end of June in Ghent, Belgium. I rented a car in Paris and drove to Caen and then vacationed in Brittany among the spectacular Neolithic monuments that remain from 6500 years ago. I also saw family in The Netherland before going to Gent. The Brexit vote happened during my stay as did real conversations about the E.U., very different from before. One conference participant cancelled because he was ashamed to be British. Map of the first part of my trip, with the arrows pointing to some of the major areas I visited in France Normandy I spent four days in Caen, Normandy, which was a city much beloved by William the Conqueror and his wife Mathilde. Bayoux, with its famous carpet, is not far but I didn’t visit that. Both William and Mathilda built monasteries to convince the pope into ok-ing their marriage. Below are some pictures of Caen. Very little but interesting street art The city of churches A famous recipee from Caen but not for vegans And more street art The parking garage I had trouble getting out Many bookstores… of! After Caen, I visited Mont St Michel; its size is immense. Before the church was built, there had been a pointed rock – pyramid-like. To construct the church, they first built four crypts around the point and then put the church on the plateau formed that way. The building styles vary depending in which ages they were built: Norman, to Gothic, to Classic. -

Island Meditation Parkland Features Stonehenge-Like Monuments

Island Meditation Parkland features Stonehenge-like Monuments (SEATTLE, Washington) - On a 72-acre parcel logged 20 years ago, forest, streams, ponds, and a peat bog have found new life as "Earth Sanctuary." A 500-year master plan for its restoration now guides the future of this Whidbey Island nature reserve and meditation parkland north of Seattle. More than 4,000 plants from 60 native species are being planted in the first phase of the plan, according to Dan Borroff, the project's award-winning landscape designer. The remarkable project created by a remarkable visionary, Chuck Pettis, has the environmental goal of restoring the landscape's old growth forest, wetlands, and streams - as well as providing habitat for the greatest possible diversity of bird and animal species native to Whidbey Island. See http://www.EarthSanctuary.org. "Earth Sanctuary is designed to restore wholeness to the human spirit, as well as to the natural environment" says Pettis, noted for his megalithic Stonehenge-like environmental artworks, as well as his writings. Visitors, on a reservation basis, are welcome to walk the two miles of Earth Sanctuary's forested paths and to meditate at the sites of the environmental artworks. The stone structures, designed as focal points for meditation, include a labyrinth, a dolmen, and a stone circle. In Borroff's view, planning for human response - both emotional and intellectual - is an integral part of good design. He describes his plant placement choices as "enhanced environmentalism." Borroff believes that the project will "nurture our spirit and transform and re-empower our passion for the land." Pettis, author of Secrets of Sacred Space: Discover and Create Places of Power ($20, Llewellyn), has financed the entire project with personal funds. -

Reading – Stonehenge Comprehension

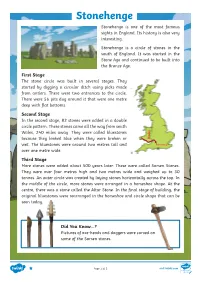

Stonehenge Stonehenge is one of the most famous sights in England. Its history is also very interesting. Stonehenge is a circle of stones in the south of England. It was started in the Stone Age and continued to be built into the Bronze Age. First Stage The stone circle was built in several stages. They started by digging a circular ditch using picks made from antlers. There were two entrances to the circle. There were 56 pits dug around it that were one metre deep with flat bottoms. Second Stage In the second stage, 82 stones were added in a double circle pattern. These stones came all the way from south Wales, 240 miles away. They were called bluestones because they looked blue when they were broken or wet. The bluestones were around two metres tall and over one metre wide. Third Stage More stones were added about 500 years later. These were called Sarsen Stones. They were over four metres high and two metres wide and weighed up to 30 tonnes. An outer circle was created by laying stones horizontally across the top. In the middle of the circle, more stones were arranged in a horseshoe shape. At the centre, there was a stone called the Altar Stone. In the final stage of building, the original bluestones were rearranged in the horseshoe and circle shape that can be seen today. Did You Know…? Pictures of axe-heads and daggers were carved on some of the Sarsen stones. Page 1 of 2 visit twinkl.com Stonehenge The stones had bumps and holes carved into them so that they fit together. -

Journal of Neolithic Archaeology

Journal of Neolithic Archaeology 6 December 2019 doi 10.12766/jna.2019S.3 The Concept of Monumentality in the Research Article history: into Neolithic Megaliths in Western France Received 14 March 2019 Reviewed 10 June 2019 Published 6 December 2019 Luc Laporte Keywords: megaliths, monumentality, Abstract western France, Neolithic, architectures This paper focuses on reviewing the monumentality associated Cite as: Luc Laporte: The Concept of Monumen- with Neolithic megaliths in western France, in all its diversity. This tality in the Research into Neolithic Megaliths region cannot claim to encompass the most megaliths in Europe, in Western France. but it is, on the other hand, one of the rare regions where mega- In: Maria Wunderlich, Tiatoshi Jamir, Johannes liths were built recurrently for nearly three millennia, by very differ- Müller (eds.), Hierarchy and Balance: The Role of ent human groups. We will first of all define the terms of the debate Monumentality in European and Indian Land- by explaining what we mean by the words monuments and meg- scapes. JNA Special Issue 5. Bonn: R. Habelt 2019, aliths and what they imply for the corresponding past societies in 27–50 [doi 10.12766/jna.2019S.3] terms of materiality, conception of space, time and rhythms. The no- tion of the architectural project is central to this debate and it will be Author‘s address: presented for each stage of this very long sequence. This will then Luc Laporte, DR CNRS, UMR lead to a discussion of the modes of human action on materials and 6566 ‐ Univ. Rennes the shared choices of certain past societies, which sometimes inspire [email protected] us to group very different structures under the same label.