The Re-Framing of Historic Architecture and Urban Space in Contemporary Morocco (1990-Present)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morocco Hides Its Secrets Well; Who Can Riad in Marrakesh, Morocco

INTERIORS TexT KALPANA SUNDER A patio with a pool at the centre of a Morocco hides its secrets well; who can riad in Marrakesh, Morocco. A riad imagine the splendour of a riad? Slip away is known for the lush greenery that from the hustle and bustle of aggressive is intrinsic to its open-air courtyard, street vendors and step into a cocoon of making it an oasis of peace. tranquillity. Frank Waldecker/Look/Dinodia Frank 74•JetWings•December 2014 JetWings•December 2014•75 Interiors AM IN THE lovely rose-pink Moroccan Above: View from the of terracotta roofs and legions of satellite dishes. town of Marrakesh, on the fringes of the rooftop of a riad that The minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque, the tallest lets you see all the Sahara, and in true Moroccan spirit, I’m way to the medina building in the city, is silhouetted against a crimson staying at a riad. Riads are traditional (the old walled part) sky; in the distance, the evocative sound of the Moroccan homes with a central courtyard of Marrakesh. muezzin called the faithful to prayer. With arched garden; in fact, the word riad is derived Below: A traditional cloisters, pots of lush tangerine bougainvillea and fountain in the inner from the Arabic word for garden. They offer courtyard of a riad in tiled courtyards, this is indeed a visual feast. refuge from the clamour and sensory overload of Fez, Morocco’s third the streets, as well as protection from the intense largest city, brings WHAT LIES WITHIN a sense of coolness cold of the winter and fiery warmth of the summer. -

Cultural Morocco FAM

Cultural Morocco FAM CULTURAL MOROCCO Phone: +1-800-315-0755 | E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cultureholidays.com CULTURE HOLIDAYS Cultural Morocco FAM Tour Description Morocco is a gateway to Africa and a country of dizzying diversity. Here you'll find epic mountain ranges, ancient cities, sweeping deserts – and warm hospitality. Morocco is quickly becoming one of the world’s most sought-after tourist destinations. From Casablanca through Rabat and Tangier at the tip of the continent; from the infinite blue labyrinth streets of Chefchaouen, and down to Fez, and still further south to the ever-spreading dunes of Erg Chebbi in the Sahara Desert; over to Marrakech, and the laid-back coastal town of Essaouira, Morocco has an abundance of important natural and historical assets. Marrakech Known as the capital of Morocco under the reign of Youssef Ben Tachfine, this “Pearl of the South” known as Marrakesh, remains one of the top attractions of tourists . Fez in the north of Morocco is a crucial center of commerce and industry (textile mills, refineries, tanneries and soap), thus making crafts and textiles an important part of the city’s past and present economy. The city, whose old quarters are classified world heritage by UNESCO, is a religious and intellectual center as well as an architectural gem. Rabat is the capital of Morocco and is a symbol of continuity in Morocco. At the heart of the city, stands the Hassan Tower, the last vestige of an unfinished mosque. Casablanca Known as the international metropolis whose development is inseparable from the port activity, Casablanca is a major international business hub. -

Bioclimatic Devices of Nasrid Domestic Buildings

Bioclimatic Devices of Nasrid Domestic Buildings Luis José GARCÍA-PULIDO studies in ARCHITECTURE, HISTORY & CULTURE papers by the 2011-2012 AKPIA@MIT visiting fellows AKPIA@MIT 2 The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 3 2011-2012 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6.1.A.1. Control of Spaces and Natural Light 6.1.A.2. Reflecting Surfaces 2. CLIMATIC CHANGES IN THE PAST AND THEIR INFLUENCES 6.1.A.3. North-South Orientation 6.1.A.4. Microclimate Provided by Courtyards IN SOCIETIES 6.1.A.5. Spatial Dispositions around the Courtyard. The 2.1. The Roman Climatic Optimum Sequence Patio-Portico-Qubba/Tower 2.2. The Early Medieval Pessimum 6.1.B. Indirect Methods of Passive Refrigeration (Heat 2.3. The Medieval Warm Period Dissipation) 2.4. The Little Ice Age 6.1.B.1. Ventilation 6.1.B.2. Radiation 6.1.B.3. Evaporation and Evapotranspiration 3. BUILDING AGAINST A HARSH CLIMATE IN THE ISLAMIC WORLD 7. BIOCLIMATIC DEVICES IN OTHER ISLAMIC REGIONS 3.1. Orientation and Flexibility WITH COMPARABLE CLIMATOLOGY TO THE SOUTHEAST 3.2. Shading IBERIAN PENINSULA 3.3. Ventilation 7.1 The North West of Maghreb 7.1.1. The Courtyard House in the Medinas of North Maghreb 4. COURTYARD HOUSES 7.2 The Anatolian Peninsula 4.1. The Sequence from the Outside to the Courtyard 7.2.1. Mediterranean Continental Climate 4.2. Taming the Climate 7.2.2. Mediterranean Marine Climate 7.2.3. Mediterranean Mountainous Climate 5. NASRID HOUSE TYPOLOGY 7.2.4. Dry and Hot Climate 7.2.5. -

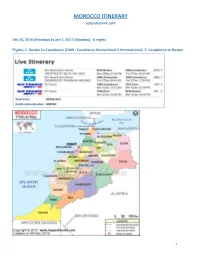

MOROCCO ITINERARY Xplorationink.Com

MOROCCO ITINERARY xplorationink.com Dec 26, 2016 (Monday) to Jan 2, 2017 (Monday) - 6 niGHts FliGHts: 1. Boston to Casablanca (CMN - Casablanca MoHammed V International) 2. Casablanca to Boston 1 SCHEDULE: 1. night1 - Dec 27th (Tuesday): arrive into Casablanca at 12:20pm - Train to Fes 2. night2 - Dec 28th (Wednesday): Fes 3. night3 - Dec 29th (Thursday): Fes to Marrakech 4. night4 - Dec 30th (Friday): Marrakech 5. night5 - Dec 31st (Saturday): NYE in Marrakech 6. night6 - Jan 1st (Sunday): New Years Day - train from Marrakech to Casablanca 7. Jan 2nd (Monday): Fly out of Casablanca to Boston then LAX HOTEL: NIGHT 1 & 2: FES check in 12.27 (Tuesday) cHeckout 12.29 (THursday) 2 NIGHT 3: MARRAKESH check in 12.29 (THursday) cHeckout 12.30 (Friday) NIGHT 4: Zagora Desert Camp site overniGHt witH camel ride. Book wHen you Get tHere. Several tours offer this. It’s definitely a must! 3 NIGHT 5: MARRAKESH checkin 12.31 (Saturday) cHeckout 01.01 (Sunday) 4 NIGHT 6: CASABLANCA check in 01.01 (Sunday) cHeckout 01.02 (Monday) 10 miles from CMN airport Random Notes: 1. Rabat to Fes: ~3 hours by bus/train ~$10 2. Casablanca to Marrakesh: ~3 hours by bus/train ~$10 3. Casablanca to Rabat: ~1 hour by train ~$5 4. Fes to Chefchaouen (blue town): 3 hours 20 minutes by car 5. No Grand Taxis (for long trips. Take the bus or train) 6. Camel 2 day/1night in Sahara Desert: https://www.viator.com/tours/Marrakech/Overnight-Desert-Trip- from-Marrakech-with-Camel-Ride/d5408-8248P5 7. 1 USD = 10 Dirhams. -

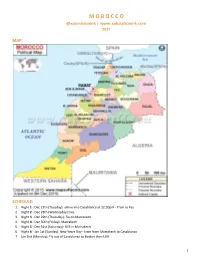

M O R O C C O @Xplorationink | 2017

M O R O C C O @xplorationink | www.xplorationink.com 2017 MAP: SCHEDULE: 1. Night 1 - Dec 27th (Tuesday): arrive into Casablanca at 12:20pm - Train to Fes 2. Night 2 - Dec 28th (Wednesday): Fes 3. Night 3 - Dec 29th (Thursday): Fes to Marrakech 4. Night 4 - Dec 30th (Friday): Marrakech 5. Night 5 - Dec 31st (Saturday): NYE in Marrakech 6. Night 6 - Jan 1st (Sunday): New Years Day - train from Marrakech to Casablanca 7. Jan 2nd (Monday): Fly out of Casablanca to Boston then LAX 1 HOTELS: FES checkin 12.27 (Tuesday) checkout 12.29 (Thursday) Algila Fes Hotel: 1-2-3/17, Akibat Sbaa Douh Fes, 30110 MA MARRAKESH checkin 12.29 (Thursday) checkout 12.30 (Friday) Riad Le Jardin d’Abdou: ⅔ derb Makina Arset bel Baraka, Marrakech, 40000 MARRAKESH checkin 12.31 (Saturday) checkout 01.01 (Sunday) Riad Yasmine Hotel: 209 Diour Saboun - Bab Taghzout, Medina, Marrakech, 40000 CASABLANCA checkin 01.01 (Sunday) checkout 01.02 (Monday) 10 miles from CMN airport Club Val D Anfa Hotel: Angle Bd de l’Ocean Atlantique &, Casablanc, 20180 ADDITIONAL NOTES: 1. Rabat to Fes: ~3 hours by bus/train ~$10 2. Casablanca to Marrakesh: ~3 hours by bus/train ~$10 3. Casablanca to Rabat: ~1 hour by train ~$5 4. Fes to Chefchaouen (blue town): 3 hours 20 minutes by car 5. No Grand Taxis (for long trips. Take the bus or train) 6. Camel 2 day/1night in Sahara Desert: https://www.viator.com/tours/Marrakech/Overnight-Desert-Trip-from-Marrakech-with-Camel-Ride/d5408-8248P5 7. 1 USD = 10 Dirhams. -

Tourism Geography & Map Work

HAND OUT FOR UGC NSQF SPONSORED ONE YEAR DILPOMA IN TRAVEL & TORUISM MANAGEMENT PAPER CODE: DTTM C206 TOURISM GEOGRAPHY & MAP WORK SEMESTER: SECOND PREPARED BY MD ABU BARKAT ALI UNIT-I: 1.IMPORTANCE OF GEOGRAPHY: Geography involves the study of various locations and how they interact based on factors such as position, culture, and environment. This can involve anything from a basic idea of where each state is in the United States, to an in-depth understanding of the population density and economic stability of various countries. A thorough grasp of this subject has immense implications on the travel industry, specifically for those in the hotel management field. As an aspiring hotel manager within the southern California area, an in-depth education of geography would help me to understand cultural differences, travel patterns, evolution of tourism in the area, and new or non traditional destinations. An understanding of these various aspects of geography would assist in the improvement of my guest service practices, marketing strategies, and investment plans, which would in turn increase the popularity and revenue of my particular hotel. Though it is critical to have a general understanding of the cultural differences a location possesses when you plan on traveling abroad, it is equally important when considering inbound tourism within the context of the hotel industry. A hotel manager must have a strong understanding of not only the local culture, but of a variety of popular cultures around the world. For example, if I am managing a hotel near the Los Angeles area and I see that a large tourist group from Japan has booked an extended vacation, it is in my best interest to research the customs and traditions of Japanese culture. -

Weddings & Honeymoons

BEST:BEST: STUNNINGSTUNNING VENUESVENUES | DREAM HOTELS | ROMANTIC GETAWAYSGETAWAYS INDIA&INDIA SOUTH ASIA & SOUTH ASIA WEDDINGS SPECIALSPECIAL EDITIONEDITION HONEYMOONS 2018-19 2018-19 / `150 & NATURALLY PLAYFUL BIPASHABIPASHA BASU & KARANKARAN SINGHSINGHN& GROVER ONON FINDINGFINDING #MONKEYLOVE An Unforgettable room decoration, enjoy a private escort in the Disney® WEDDING WITH A DISNEY TOUCH Celebration at Parks with a dedicated VIP Guide, take advantage of a Dazzle your guests by hosting your wedding three- private shopping experience or oer the ultimate Princess day celebration at Disneyland® Paris, a unique DISNEYLAND PARIS or Pirate experience to your little ones… place where magic and love come together in the At Disneyland® Paris, every moment is worth an most enchanting setting. No matter how grand The perfect destination for an exceptional luxury retreat at exclusive celebration. All private events and celebrations your wishes, our largest venues can host up to 1000 the heart of Europe, Paris is where you can enjoy French art are custom-made according to your unique wishes: a guests and are totally customisable. You can enjoy an 3939 de vivre through a unique choice of luxury shopping, fi nest gourmet brunch with Alice in Wonderland, a Parisian exclusive use of Disney® Parks after opening hours night at Place de Rémy, a Royal Tea Time in the company cuisine and sumptuous palaces. for your Sangeet Bollywood party. As night falls, of Disney Princesses, a marvelous Super Heroes dinner… benefit from a festive evening of attractions, dining, WAYWAY let your fantasy speak! You can also enjoy attractions just spectacular shows and dance late into the night! for yourself with a privatisation of the Disney® Parks. -

Danish-Arab Partnership Programme (DAPP) 2017-2022

Danish-Arab Partnership Programme (DAPP) 2017-2022 Key results to be achieved in Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan File No. 2016-11680 and regionally. Country Middle East and North Africa Human rights defenders have sustained or developed their ability Responsible Unit MENA to promote and protect human rights. Sector Governance, human rights, media Gender equality will be improved according to SDG targets and economic opportunities related to law reform, political participation, gender based 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 violence and sexual and reproductive health and rights. Commitment 200 200 200 200 200 The legal environment and managerial foundation for 22 free media outlets will be enhanced. Projected annual 120 200 200 200 200 80 disbursement Competence of 125 local partners, private sector businesses enhanced to effectively engage in/promote youth employment. Duration 1.07.2017 – 31.06.2022 Close to 10.000 targeted youth employed and approximately 10 DK national 06.32.09.10 labour market legislations approved according to ILO standards. budget account 06.32.09.20 Justification for support code DAPP is aligned with Danish foreign policy interests in the Desk officer Kurt Mørck Jensen region. DAPP addresses challenges and opportunities in a Financial officer Mads Ettrup volatile political context and is based on demand from local SDGs relevant for Programme partners and lessons learned over ten years. Support for governance and economic opportunities is highly relevant in the MENA context of pressure on human rights and No No Good Health Quality Gender Clean youth unemployment. Poverty Hunger Education Equality Water, Sanitation Despite the challenging context, DAPP’s partnership strategy has demonstrated tangible results in specific intervention areas. -

Music-Induced Spirit Possession Trance in Morocco: Implications for Anthropology and Allied Disciplinesِ

MUSIC-INDUCED SPIRIT POSSESSION TRANCE IN MOROCCO: IMPLICATIONS FOR ANTHROPOLOGY AND ALLIED DISCIPLINESِ By KAMAL FERIALI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Kamal Feriali 2 To Truffiaut 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks are due first and foremost to the hundreds of Moroccan trancers and other field informants in the Medinas of Meknès and Moulay Idriss, and the surrounding villages, who contributed precious cultural material for this work. Mr. Driss Nouijiai, my field assistant, is particularly recognized for immensely facilitating the process of data collection. At the University of Florida, I acknowledge my doctoral committee chair, Dr. Elizabeth Guillette, as well as every other member of my committee: Dr. Sylvie Blum, Dr. Abdoulaye Kane, Dr. Paul Magnarella, and Dr. Vasu Narayanan. I appreciate their support in various ways, and their willingness to dedicate precious time to reading and/or commenting my work. To Dr. Paul Magnarella, in particular, I furthermore owe several years of intellectual and academic mentoring. Special thanks go to the staff of the Graduate School Editorial Office for having individually assisted me multiple times with the formatting of this work throughout Spring 2009. I was grateful for their welcoming attitude even during the busiest season of the Editorial Office prior to dissertation submission deadlines. Their personable care has made a huge difference. I warmly appreciate the communities of St. Augustine’s Catholic Church in Gainesville, FL, Eglise Notre Dame des Oliviers, and Centre St. Antoine in Meknès, Morocco, for accompanying me over the years. -

Geometric Patterns in Islamic Decoration

GEOMETRIC PATTERNS IN ISLAMIC DECORATION A PARAMETRIC ENVISION OF PORTUGUESE AND AZERBAIJAN ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC MOTIFS AYDAN AGHABAYLI Bachelor of Architecture Dissertation to Obtain Master Degree in Architecture Scientific Advisors: PEDRO MIGUEL GOMES JANUÁRIO PAULO JORGE GARCIA PEREIRA Members of Jury: ANTÓNIO CASTELBRANCO (President) LUÍS MIGUEL COTRIM MATEUS (Arguer) Faculty of Architecture of the University of Lisbon, Lisbon, 2016 GEOMETRIC PATTERNS IN ISLAMIC DECORATION | A Parametric Envision of Portuguese and Azerbaijan Islamic Geometric Motifs 2 | Page GEOMETRIC PATTERNS IN ISLAMIC DECORATION | A Parametric Envision of Portuguese and Azerbaijan Islamic Geometric Motifs GEOMETRIC PATTERNS IN ISLAMIC DECORATION A PARAMETRIC ENVISION OF PORTUGUESE AND AZERBAIJAN ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC MOTIFS Author: Aydan Aghabayli Scientific Advisors: Paulo Jorge Garcia Pereira and Pedro Miguel Gomes Januario Master in Architecture July, 2016 ABSTRACT Portugal and Azerbaijan had a strong Islamic influence in the past. Even nowadays, we can experience signs of this cultural heritage, and the tangible and intangible impact in both countries. It is noticeable in many areas likewise in architecture. In Portugal, despite many examples of Islamic heritage influence have been lost or destroyed, there still are in some particular cities a remarkable architecture and ornamentation legacy. On the other hand, the situation in Azerbaijan is slightly different due to the fact that the majority of Azerbaijan’s population is Muslim. Therefore, there are still many living examples of Islamic geometric motifs in architecture and eventually, a living tradition. 3 | P a g e GEOMETRIC PATTERNS IN ISLAMIC DECORATION | A Parametric Envision of Portuguese and Azerbaijan Islamic Geometric Motifs The present dissertation is part of an ongoing research project entitled “Biomimetics and Digital Morphogenesis” enrolled at the CIAUD Research Centre of the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Lisbon. -

Fez, Casablanca & Marrakech

Fez, Casablanca & Marrakech From £699 per person // 9 days Discover the vibrant, fascinating cities of Fez, Casablanca and Marrakech on this North African holiday. Travel between destinations by rail on comfortable air-conditioned trains. The Essentials What's included Historic Fez with its medieval medinas and colourful Private transfer on arrival into Fez airport tanneries First Class rail travel with seat reservations Casablanca, one of the largest and most important cities in 8 nights’ handpicked hotel accommodation with breakfast Africa Private car transfers to and from your hotels Mesmerising Marrakech, a feast for the senses Clearly-presented wallets for your rail tickets, hotel Rail travel between cities and pre-booked transfers to and vouchers and other documentation from your accommodation All credit card surcharges and complimentary delivery of your travel documents Tailor make your holiday Decide when you would like to travel Adapt the route to suit your plans Upgrade hotels and rail journeys Add extra nights, destinations and/or tours Travel to and from Morocco by rail - Suggested Itinerary - Day 1 - Arrive In Fez Let us know your flight details so that on arrival into Fez, we can arrange a transfer to meet you and take you to your hotel. You will be spending 3 nights at the Riad El Yacout (or similar). TMR RECOMMENDS: You will need to book flights yourself but if you have the time, it’s perfectly possible to travel down to Morocco by train and ferry and we can arrange this for you. We recommend at least one overnight stop en route, probably in Barcelona. -

The Meanings and Aesthetic Development of Almohad Friday Mosques

MONUMENTAL AUSTERITY: THE MEANINGS AND AESTHETIC DEVELOPMENT OF ALMOHAD FRIDAY MOSQUES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jessica Renee Streit August 2013 © 2013 Jessica Renee Streit MONUMENTAL AUSTERITY: THE MEANINGS AND AESTHETIC DEVELOPMENT OF ALMOHAD FRIDAY MOSQUES Jessica Renee Streit, Ph.D. Cornell University 2013 This dissertation examines four twelfth-century Almohad congregational mosques located in centers of spiritual or political power. Previous analyses of Almohad religious architecture are overwhelmingly stylistic and tend to simply attribute the buildings’ markedly austere aesthetic to the Almohads’ so-called fundamentalist doctrine. Ironically, the thorough compendium of the buildings’ physical characteristics produced by this approach belies such a monolithic interpretation; indeed, variations in the mosques’ ornamental programs challenge the idea that Almohad aesthetics were a static response to an unchanging ideology. This study demonstrates that Almohad architecture is a dynamic and complex response to both the difficulties involved in maintaining an empire and the spiritual inclinations of its patrons. As such, it argues that each successive building underwent revisions that were tailored to its religious and political environment. In this way, it constitutes the fully contextualized interpretation of both individual Almohad mosques and Almohad aesthetics. After its introduction, this dissertation’s second chapter argues that the two mosques sponsored by the first Almohad caliph sent a message of political and religious authority to their rivals. The two buildings’ spare, abstract ornamental system emphasized the basic dogma upon which Almohad political legitimacy was predicated, even as it distinguished Almohad mosques from the ornate sanctuaries of the Almoravids.