Invalid Unnamed Minerals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Processing

Mineral Processing Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy 1st English edition JAN DRZYMALA, C. Eng., Ph.D., D.Sc. Member of the Polish Mineral Processing Society Wroclaw University of Technology 2007 Translation: J. Drzymala, A. Swatek Reviewer: A. Luszczkiewicz Published as supplied by the author ©Copyright by Jan Drzymala, Wroclaw 2007 Computer typesetting: Danuta Szyszka Cover design: Danuta Szyszka Cover photo: Sebastian Bożek Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej Wybrzeze Wyspianskiego 27 50-370 Wroclaw Any part of this publication can be used in any form by any means provided that the usage is acknowledged by the citation: Drzymala, J., Mineral Processing, Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy, Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr., 2007, www.ig.pwr.wroc.pl/minproc ISBN 978-83-7493-362-9 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part I Introduction to mineral processing .....................................................................13 1. From the Big Bang to mineral processing................................................................14 1.1. The formation of matter ...................................................................................14 1.2. Elementary particles.........................................................................................16 1.3. Molecules .........................................................................................................18 1.4. Solids................................................................................................................19 -

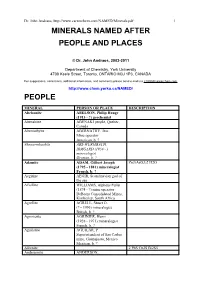

Minerals Named After Scientists

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 1 MINERALS NAMED AFTER PEOPLE AND PLACES © Dr. John Andraos, 2003-2011 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ PEOPLE MINERAL PERSON OR PLACE DESCRIPTION Abelsonite ABELSON, Philip Hauge (1913 - ?) geochemist Abenakiite ABENAKI people, Quebec, Canada Abernathyite ABERNATHY, Jess Mine operator American, b. ? Abswurmbachite ABS-WURMBACH, IRMGARD (1938 - ) mineralogist German, b. ? Adamite ADAM, Gilbert Joseph Zn3(AsO3)2 H2O (1795 - 1881) mineralogist French, b. ? Aegirine AEGIR, Scandinavian god of the sea Afwillite WILLIAMS, Alpheus Fuller (1874 - ?) mine operator DeBeers Consolidated Mines, Kimberley, South Africa Agrellite AGRELL, Stuart O. (? - 1996) mineralogist British, b. ? Agrinierite AGRINIER, Henri (1928 - 1971) mineralogist French, b. ? Aguilarite AGUILAR, P. Superintendent of San Carlos mine, Guanajuato, Mexico Mexican, b. ? Aikenite 2 PbS Cu2S Bi2S5 Andersonite ANDERSON, Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 2 Andradite ANDRADA e Silva, Jose B. Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3 de (? - 1838) geologist Brazilian, b. ? Arfvedsonite ARFVEDSON, Johann August (1792 - 1841) Swedish, b. Skagerholms- Bruk, Skaraborgs-Län, Sweden Arrhenite ARRHENIUS, Svante Silico-tantalate of Y, Ce, Zr, (1859 - 1927) Al, Fe, Ca, Be Swedish, b. Wijk, near Uppsala, Sweden Avogardrite AVOGADRO, Lorenzo KBF4, CsBF4 Romano Amedeo Carlo (1776 - 1856) Italian, b. Turin, Italy Babingtonite (Ca, Fe, Mn)SiO3 Fe2(SiO3)3 Becquerelite BECQUEREL, Antoine 4 UO3 7 H2O Henri César (1852 - 1908) French b. Paris, France Berzelianite BERZELIUS, Jöns Jakob Cu2Se (1779 - 1848) Swedish, b. -

Subject Index, Volume 83, 1998

American Mineralogist, Volume 83, pages 1377–1385, 1998 SUBJECT INDEX, VOLUME 83, 1998 Actinolite 458 jadeitic pyroxene 273 Arsenic model compounds 553 AFM lithium disilicate 1008 Arsenopyrite 316 illite-smectite 762 magnesiowüstite 794 ASH system 881 nucleation and growth 147 MgMgAl-pumpellyite 220 Atmospheric CO2 1503 2+ 3+ Agrell, Stuart O., memorial of 666 Mn (Fe, Mn) 2 O4 786 Augite 419, 434 Albite glass 1141 monazite 248 Awards Al-Fe perovskite (MgSiO3) 947 monazite-(Ce) 259 Mineralogical Society of America, ac - Allanite 248 muscovite 535 ceptance of 917 Allende meteorite 970 muscovite-phengite 775 Mineralogical Society of America, pre- Almandite 1293 offretite 577 sentation of 916 27Al MAS NMR olivine 546 Roebling Medal, acceptance of 914 Al2O3+B2O3+SiO2 ± H2O 638 omphacite 419 Roebling Medal, presentation of 912 AlSiO3OH 881 paranite-(Y) 1100 B8/anti-B8 451 Ammonium illilte 58 phase egg 881 B8-FeO 451 Analcime 339, 746 phosphovanadylilte 889 Bacteria 1583 Analysis, chemical (mineral) pyrope 323, 1293 Bacterial surfaces 1399 almandite 1293 pyroxene 491 Bacterial synthesis of greigite 1469 andradite 835 rossmanite 896 Band Gap 865 anorthite 1209 rubicline 1335 Bamfordite 172 apatite 240, 1122 scandiobabingtonite 1330 Basaltic andesite 36 arsenopyrite 316 scheelite 1100 BaTi5Fe6MgO19 1323 augite 419 schorl 848 Benyacarite 400 bamfordite 172 sodic-ferri-clinoferroholmquistite 668 Berezanskite 907 biogenic magnetite 1409 sorosite 901 Bioaccumulation 1503 boralsilite 638 spessartine 1293 Biogenic magnetite 1409 bornite 1231 titanite 1168 Biogeochemistry 1418, 1494, 1593, 1426 brabantite 259 tourmaline 535, 638, 848 Biomineralization 1454, 1510 brucite 68 tremolite–actinolite–ferro-actinolite 458 Birnessite 305 buergerite 848 tschörtnerite 607 Boehmite 1209 Ca-amphibole 952 wüstite 451 Book reviews caleite 1510, 1503 xenotime 1302 Carey, J.William: Thermodynamics carbon 918 yvonite 383 of Natural Systems. -

New Minerals Approved Bythe Ima Commission on New

NEW MINERALS APPROVED BY THE IMA COMMISSION ON NEW MINERALS AND MINERAL NAMES ALLABOGDANITE, (Fe,Ni)l Allabogdanite, a mineral dimorphous with barringerite, was discovered in the Onello iron meteorite (Ni-rich ataxite) found in 1997 in the alluvium of the Bol'shoy Dolguchan River, a tributary of the Onello River, Aldan River basin, South Yakutia (Republic of Sakha- Yakutia), Russia. The mineral occurs as light straw-yellow, with strong metallic luster, lamellar crystals up to 0.0 I x 0.1 x 0.4 rnrn, typically twinned, in plessite. Associated minerals are nickel phosphide, schreibersite, awaruite and graphite (Britvin e.a., 2002b). Name: in honour of Alia Nikolaevna BOG DAN OVA (1947-2004), Russian crys- tallographer, for her contribution to the study of new minerals; Geological Institute of Kola Science Center of Russian Academy of Sciences, Apatity. fMA No.: 2000-038. TS: PU 1/18632. ALLOCHALCOSELITE, Cu+Cu~+PbOZ(Se03)P5 Allochalcoselite was found in the fumarole products of the Second cinder cone, Northern Breakthrought of the Tolbachik Main Fracture Eruption (1975-1976), Tolbachik Volcano, Kamchatka, Russia. It occurs as transparent dark brown pris- matic crystals up to 0.1 mm long. Associated minerals are cotunnite, sofiite, ilin- skite, georgbokiite and burn site (Vergasova e.a., 2005). Name: for the chemical composition: presence of selenium and different oxidation states of copper, from the Greek aA.Ao~(different) and xaAxo~ (copper). fMA No.: 2004-025. TS: no reliable information. ALSAKHAROVITE-Zn, NaSrKZn(Ti,Nb)JSi401ZJz(0,OH)4·7HzO photo 1 Labuntsovite group Alsakharovite-Zn was discovered in the Pegmatite #45, Lepkhe-Nel'm MI. -

Carnegie/DOE Alliance Center (CDAC): a CENTER of EXCELLENCE for HIGH PRESSURE SCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY

CARNEGIE/DOE ALLIANCE CENTER A Center of Excellence for High Pressure Science and Technology Supported by the Stockpile Stewardship Academic Alliances Program of DOE/NNSA Year Three Annual Report September 2006 Russell J. Hemley, Director Ho-kwang Mao, Associate Director Stephen A. Gramsch, Coordinator Carnegie/DOE Alliance Center (CDAC): A CENTER OF EXCELLENCE FOR HIGH PRESSURE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY YEAR THREE ANNUAL REPORT 1. Overview 1.1 Mission of CDAC 3 1.2 Highlights from Year 3 4 1.3 Year 3 Work Plan and Milestones 6 2. Scientific Progress 2.1 High P-T Phase Relations and Structures 10 2.2 P-V-T EOS Measurements 19 2.3 Phonons, Vibrational Thermodynamics and Elasticity 22 2.4 Plasticity, Yield Strength and Deformation 26 2.5 Electronic and Magnetic Structure and Dynamics 27 2.6 High P-T Chemistry 36 3. Education, Training, and Outreach 3.1 CDAC Graduate Students and Post-doctoral Associates 40 3.2 CDAC Collaborators 43 3.3 Undergraduate Student Participation 47 3.4 DC Area High School Outreach 49 3.5 Synergy of 21st Century High-Pressure Science and Technology Workshop 50 3.6 Visitors to CDAC 56 3.7 High Pressure Seminars 58 4. Technology Development 4.1 High P-T Experimental Techniques 60 4.2 Facilities at Brookhaven, LANSCE, and Carnegie 64 4.3 Commissioning and Activities at HPCAT 66 5. Interactions with NNSA/DP National Laboratories 5.1 Overview 67 5.2 Academic Alliance and Laboratory Collaborations 69 6. Management and Oversight 6.1 CDAC Organization and Staff 71 6.2 CDAC Oversight 73 6.3 Second Year Review 74 7. -

Valid Unnamed Minerals, Update 2012-01

VALID UNNAMED MINERALS, UPDATE 2012-01 IMA Subcommittee on Unnamed Minerals: Jim Ferraiolo*, Jeffrey de Fourestier**, Dorian Smith*** (Chairman) *[email protected] **[email protected] ***[email protected] Users making reference to this compilation should refer to the primary source (Dorian G.W. Smith & Ernest H. Nickel (2007): A System of Codification for Unnamed Minerals: Report of the SubCommittee for Unnamed Minerals of the IMA Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification. Canadian Mineralogist v. 45, p.983-1055), and to this website . Additions and changes to the original publication are shown in blue print; deletions are "greyed out and struck through". IMA Code Primary Reference Secondary Comments Reference UM1886-01-OC:HNNa *Bull. Soc. Minéral. 9 , 51 Dana (7th) 2 , 1104 Probably an oxalate but if not is otherwise similar to lecontite UM1892-01-F:CaY *Am. J. Sci. 44 , 386 Dana (7th) 2 , 37 Low analytical total because F not reported; unlike any other known fluoride 3+ UM1910-01-PO:CaFeMg US Geol. Surv. Bull. 419, 1 Am. Mineral. 34 , 513 (Ca,Fe,Mg)Fe 2(PO4)2(OH)2•2H2O; some similarities to mitridatite UM1913-01-AsO:CaCuV *Am. J. Sci. 35 , 441 Dana (7th) 2 , 818 Possibly As-bearing calciovolborthite UM1922-01-O:CuHUV *Izv. Ross. Akad. Nauk [6], 16 , 505 Dana (7th) 2 , 1048 Some similarities to sengierite 3+ UM1926-01-O:HNbTaTiU *Bol. Inst. Brasil Sc., 2 , 56 Dana (7th) 1 , 807 (Y,Er,U,Th,Fe )3(Ti,Nb,Ta)10O26; some similarities to samarskite-(Y) UM1927-01-O:CaTaTiW *Gornyi Zhurn. -

The Tennessee Meteorite Impact Sites and Changing Perspectives on Impact Cratering

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND THE TENNESSEE METEORITE IMPACT SITES AND CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON IMPACT CRATERING A dissertation submitted by Janaruth Harling Ford B.A. Cum Laude (Vanderbilt University), M. Astron. (University of Western Sydney) For the award of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT Terrestrial impact structures offer astronomers and geologists opportunities to study the impact cratering process. Tennessee has four structures of interest. Information gained over the last century and a half concerning these sites is scattered throughout astronomical, geological and other specialized scientific journals, books, and literature, some of which are elusive. Gathering and compiling this widely- spread information into one historical document benefits the scientific community in general. The Wells Creek Structure is a proven impact site, and has been referred to as the ‘syntype’ cryptoexplosion structure for the United State. It was the first impact structure in the United States in which shatter cones were identified and was probably the subject of the first detailed geological report on a cryptoexplosive structure in the United States. The Wells Creek Structure displays bilateral symmetry, and three smaller ‘craters’ lie to the north of the main Wells Creek structure along its axis of symmetry. The question remains as to whether or not these structures have a common origin with the Wells Creek structure. The Flynn Creek Structure, another proven impact site, was first mentioned as a site of disturbance in Safford’s 1869 report on the geology of Tennessee. It has been noted as the terrestrial feature that bears the closest resemblance to a typical lunar crater, even though it is the probable result of a shallow marine impact. -

Shocked Monazite Chronometry: Integrating Microstructural and in Situ Isotopic Age Data for Determining Precise Impact Ages

Contrib Mineral Petrol (2017) 172:11 DOI 10.1007/s00410-017-1328-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Shocked monazite chronometry: integrating microstructural and in situ isotopic age data for determining precise impact ages Timmons M. Erickson1 · Nicholas E. Timms1 · Christopher L. Kirkland1 · Eric Tohver2 · Aaron J. Cavosie1,3 · Mark A. Pearce4 · Steven M. Reddy1 Received: 30 August 2016 / Accepted: 10 January 2017 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2017 Monazite is a robust geochronometer and {110}, {212}, and type two (irrational) twin planes with Abstract ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ occurs in a wide range of rock types. Monazite also records rational shear directions in [011] and [110]. SIMS U–Th– shock deformation from meteorite impact but the effects Pb analyses of the plastically deformed parent domains of impact-related microstructures on the U–Th–Pb sys- reveal discordant age arrays, where discordance scales with tematics remain poorly constrained. We have, therefore, increasing plastic strain. The correlation between discord- analyzed shock-deformed monazite grains from the central ance and strain is likely a result of the formation of fast uplift of the Vredefort impact structure, South Africa, and diffusion pathways during the shock event. Neoblasts in impact melt from the Araguainha impact structure, Brazil, granular monazite domains are strain-free, having grown using electron backscatter diffraction, electron microprobe during the impact events via consumption of strained par- elemental mapping, and secondary ion mass spectrometry ent grains. Neoblastic monazite from the Inlandsee leu- (SIMS). Crystallographic orientation mapping of monazite cogranofels at Vredefort records a 207Pb/206Pb age of grains from both impact structures reveals a similar com- 2010 ± 15 Ma (2σ, n = 9), consistent with previous impact bination of crystal-plastic deformation features, includ- age estimates of 2020 Ma. -

IMA Master List

The New IMA List of Minerals – A Work in Progress – Update: February 2013 In the following pages of this document a comprehensive list of all valid mineral species is presented. The list is distributed (for terms and conditions see below) via the web site of the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association, which is the organization in charge for approval of new minerals, and more in general for all issues related to the status of mineral species. The list, which will be updated on a regular basis, is intended as the primary and official source on minerals. Explanation of column headings: Name: it is the presently accepted mineral name (and in the table, minerals are sorted by name). Chemical formula: it is the CNMNC-approved formula. IMA status: A = approved (it applies to minerals approved after the establishment of the IMA in 1958); G = grandfathered (it applies to minerals discovered before the birth of IMA, and generally considered as valid species); Rd = redefined (it applies to existing minerals which were redefined during the IMA era); Rn = renamed (it applies to existing minerals which were renamed during the IMA era); Q = questionable (it applies to poorly characterized minerals, whose validity could be doubtful). IMA No. / Year: for approved minerals the IMA No. is given: it has the form XXXX-YYY, where XXXX is the year and YYY a sequential number; for grandfathered minerals the year of the original description is given. In some cases, typically for Rd and Rn minerals, the year may be followed by s.p. -

Ebberly Ann Maclagan

Constraints on emplacement and timing of the Steen River impact structure, Alberta, Canada by Ebberly Ann MacLagan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences University of Alberta © Ebberly Ann MacLagan, 2018 ABSTRACT The Steen River impact structure (SRIS) is a buried, complex crater located in NW Alberta, Canada. It was discovered in the mid 1900’s and was initially thought to be an endogenic igneous intrusion. With the growth of impact studies on Earth and other planets, the SRIS was recognized as such in the 1960’s. Since then, numerous exploratory wells have been drilled in and around the structure to assess its economic potential. While many of these wells are proprietary, three cores collected in 2000 are available for research and have been the focus of the most recent SRIS studies. A ubiquitous product of impact events is impact breccia, which may contain clasts of target material and melt. At the well-studied Ries impact structure in Germany, this breccia is classified as suevite. The impact breccia observed at the SRIS is similar to the Ries suevite; however, the term “suevite” has been applied to many impact structures and its formation mechanism is still debated. In previous studies, three cores from the SRIS (ST001, ST002, and ST003) were logged by hand and characterized in detail using thin sections; however, a representative, yet detailed, mineralogical overview of the core was lacking. In this thesis, hyperspectral imaging was used to quickly scan the three cores and make detailed mineralogical maps of each. -

New Insights Into the Zircon-Reidite Phase Transition

American Mineralogist, Volume 104, pages 830–837, 2019 New insights into the zircon-reidite phase transition CLAUDIA STANGARONE1,†, ROSS J. ANGEL1,*, MAURO PRENCIPE2, BORIANA MIHAILOVA3, AND MATTEO ALVARO1 1Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Pavia, Via A. Ferrata 1, I-27100 Pavia, Italy 2Earth Sciences Department, University of Torino, Via Valperga Caluso 35, I-10125 Torino, Italy 3Department of Earth Sciences, University of Hamburg, Grindelallee 48, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany ABSTRACT The structure, the elastic properties, and the Raman frequencies of the zircon and reidite polymorphs of ZrSiO4 were calculated as a function of hydrostatic pressure up to 30 GPa using HF/DFT ab initio calculations at static equilibrium (0 K). The softening of a silent (B1u) mode of zircon leads to a phase transition to a “high-pressure–low-symmetry” (HPLS) ZrSiO4 polymorph with space group I42d and cell parameters a = 6.4512 Å, c = 5.9121 Å, and V = 246.05 Å3 (at 20 GPa). The primary coordina- tion of SiO4 and ZrO8 groups in the structure of zircon is maintained in the high-pressure phase, and the new phase deviates from that of zircon by the rotation of SiO4 tetrahedra and small distortions of the ZrO8 dodecahedra. The new polymorph is stable with respect to zircon at 20 GPa and remains a dynamically stable structure up to at least 30 GPa. On pressure release, the new phase reverts back to the zircon structure and, therefore, cannot be quenched in experiments. In contrast, the transformation from zircon to reidite is reconstructive in nature and results in a first-order transition with a volume and density change of about 9%. -

STRONG and WEAK INTERLAYER INTERACTIONS of TWO-DIMENSIONAL MATERIALS and THEIR ASSEMBLIES Tyler William Farnsworth a Dissertati

STRONG AND WEAK INTERLAYER INTERACTIONS OF TWO-DIMENSIONAL MATERIALS AND THEIR ASSEMBLIES Tyler William Farnsworth A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Chemistry. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Scott C. Warren James F. Cahoon Wei You Joanna M. Atkin Matthew K. Brennaman © 2018 Tyler William Farnsworth ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Tyler William Farnsworth: Strong and weak interlayer interactions of two-dimensional materials and their assemblies (Under the direction of Scott C. Warren) The ability to control the properties of a macroscopic material through systematic modification of its component parts is a central theme in materials science. This concept is exemplified by the assembly of quantum dots into 3D solids, but the application of similar design principles to other quantum-confined systems, namely 2D materials, remains largely unexplored. Here I demonstrate that solution-processed 2D semiconductors retain their quantum-confined properties even when assembled into electrically conductive, thick films. Structural investigations show how this behavior is caused by turbostratic disorder and interlayer adsorbates, which weaken interlayer interactions and allow access to a quantum- confined but electronically coupled state. I generalize these findings to use a variety of 2D building blocks to create electrically conductive 3D solids with virtually any band gap. I next introduce a strategy for discovering new 2D materials. Previous efforts to identify novel 2D materials were limited to van der Waals layered materials, but I demonstrate that layered crystals with strong interlayer interactions can be exfoliated into few-layer or monolayer materials.