Reality and Methods in Documentary Filmmaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documentary Tensions and the Filmmaker in the Frame

Documentary tensions and the Filmmaker in the Frame By Trent Griffiths BA, Grad Cert Film Video Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Deakin University November 2014 Abstract This thesis examines in detail three films in which the filmmaker is present within the frame: Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man (2005), Anna Broinowski’s Forbidden Lie$ (2007), and Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film (2011). Each of these films offers a distinct insight into the conceptual tensions that arise when a filmmaker is framed as both a specific subject and the author of the film. On this basis the thesis proposes a significant category of contemporary documentary – here called the Filmmaker in the Frame films – of which the three films analysed are emblematic. Defining this category brings to the fore the complex issues that arise when filmmakers engage with their own authorial identity while remaining committed to representing an ‘other.’ Through detailed textual analysis of these documentaries the thesis identifies how questions of authorship are explicitly shown as negotiated between the filmmaker, the people they film, and the situations in which they participate. This negotiation of authorship also reveals the authority of the filmmaker to be constructed as a particular kind of performance, enacted in the moments of filming. In order to analyse the presence of the filmmaker in these films, the thesis draws together Stella Bruzzi’s notion of documentary as the result of the ‘collision’ between apparatus and subject, and Judith Butler’s notion of the performativity of identity. The idea that documentaries might propose forms of negotiated and performed authorship is significant because it disturbs the theoretical opposition between subjectivity and objectivity that underlies dominant discourses of documentary. -

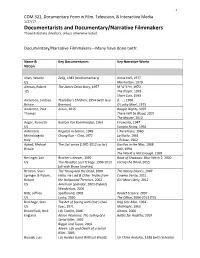

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

Evaluation of the Role of Iran National Museum in the Cultural Tourism in Iran

EVALUATION OF THE ROLE OF IRAN NATIONAL MUSEUM IN THE CULTURAL TOURISM IN IRAN Omid Salek Farokhi Per citar o enllaçar aquest document: Para citar o enlazar este documento: Use this url to cite or link to this publication: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/667713 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). -

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD 15 20795 Those Who Wish Me Dead 2021 DVD 15 20794 The Father 2020 DVD 12 20793 A Quiet Place Part 2 2020 DVD 15 20792 Cruella 2021 DVD 12 20791 Luca 2021 DVD U 20790 Five Feet Apart 2019 DVD 12 20789 Sound of Metal 2019 BR 15 20788 Promising Young Woman 2020 DVD 15 20787 The Mountain Between Us 2017 DVD 12 20786 The Bleeder 2016 DVD 15 20785 The United States Vs Billie Holiday 2021 DVD 15 20784 Nomadland 2020 DVD 12 20783 Minari 2020 DVD 12 20782 Judas and the Black Messiah 2021 DVD 15 20781 Ammonite 2020 DVD 15 20780 Godzilla Vs Kong 2021 DVD 12 20779 Imperium 2016 DVD 15 20778 To Olivia 2021 DVD 12 20777 Zack Snyder's Justice League 2021 DVD 15 20776 Raya and the Last Dragon 2021 DVD PG 20775 Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar 2021 DVD 15 20774 Chaos Walking 2021 DVD 12 20773 Treacle Jr 2010 DVD 15 20772 The Swordsman 2020 DVD 15 20771 The New Mutants 2020 DVD 15 20770 Come Away 2020 DVD PG 20769 Willy's Wonderland 2021 DVD 15 20768 Stray 2020 DVD 18 20767 County Lines 2019 BR 15 20767 County Lines 2019 DVD 15 20766 Wonder Woman 1984 2020 DVD 12 20765 Blackwood 2014 DVD 15 20764 Synchronic 2019 DVD 15 20763 Soul 2020 DVD PG 20762 Pixie 2020 DVD 15 20761 Zeroville 2019 DVD 15 20760 Bill and Ted Face the Music 2020 DVD PG 20759 Possessor 2020 DVD 18 20758 The Wolf of Snow Hollow 2020 DVD 15 20757 Relic 2020 DVD 15 20756 Collective 2019 DVD 15 20755 Saint Maud 2019 DVD 15 20754 Hitman Redemption 2018 DVD 15 20753 The Aftermath 2019 DVD 15 20752 Rolling Thunder Revue 2019 -

Olmo and the Seagull

Nadica Denic Student nr: 10603557 [email protected] EMBODYING HYBRIDITY: Enactive-ecological approach to filmic self-perception and self- enactment in contemporary docufiction film Research Master Thesis Department of Media Studies University of Amsterdam Supervisor: Patricia Pisters Second reader: Abe Geil I express my gratitude to a number of people. I am thankful to Patricia Pisters for her guidance through my film-philosophical curiosities. To my family, for always being there. And to Adel, Mare and Matthias, who always made friendship a priority. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Enactive-Ecological Theory of Perception ................................................................... 7 1.1 Embodied Cognition ............................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Ecological Affordances ....................................................................................................... 10 1.3 Cultural Modification of Affordances ................................................................................. 12 1.4 Mediation of Bodily Presence ............................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2: Affordances of Filmic Self-Perception ....................................................................... 19 2.1 Mediating Spatiality ........................................................................................................... -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 500 Nations DVD-0778 10 Days to D-Day DVD-0690 500 Years Later DVD-5438 180 DVD-3999 56 Up DVD-8322 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 60's DVD-0410 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 7 Years DVD-4399 1964 DVD-7724 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 70's Dimension DVD-1568 1993 World Trade Center Bombing DVD-1891 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 900 Women DVD-2068 DVD-4941 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 21 Up DVD-1061 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Abolitionists DVD-7362 24 City DVD-9072 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 28 Up DVD-1066 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 35 Up DVD-1072 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Act of Killing DVD-4434 42 Up DVD-1079 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 -

Jafar Panahi's Taxi

presents JAFAR PANAHI’S TAXI Written, Produced and Directed by Jafar Panahi 2015 Berlin Film Festival- Winner Golden Bear 2015 Toronto International Film Festival Iran | 82 minutes | 2015 | In Farsi with English Subtitles www.kinolorber.com/press Kino Lorber, Inc. 333 West 39th St. Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Publicity Contact: Rodrigo Brandao O: (212) 629-6880 M: 917.434.6168 Synopsis Internationally acclaimed director Jafar Panahi (This is Not a Film) drives a yellow cab through the vibrant streets of Tehran, picking up a diverse (and yet representative) group of passengers in a single day. Each man, woman, and child candidly expresses his or her own view of the world, while being interviewed by the curious and gracious driver/director. His camera, placed on the dashboard of his mobile film studio, captures a spirited slice of Iranian society while also brilliantly redefining the borders of comedy, drama and cinema. Director’s Statement I’m a filmmaker. I can’t do anything else but make films. Cinema is my expression and the meaning of my life. Nothing can prevent me from making films. Because when I'm pushed into the furthest corners I connect with my inner self. And in such private spaces, despite all limitations, the necessity to create becomes even more of an urge. Cinema as an art becomes my main preoccupation. That is the reason why I have to continue making films under any circumstances to pay my respects and feel alive. Director Biography Jafar Panahi was born in 1960 in Mianeh, Iran. -

Spirited Away Bus174 End of the Century How to Train Your Dragon

Spirited Away Bus174 End of the Century How to Train Your Dragon 2 My Architect The Rocket The Prestige Best Worst Movie Gangs of New York 2 Days in Paris The Blue Room Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back Bruce Almighty Les Parapluises de Cherbourg Bloody Sunday Deep Water High Fidelity MI Rogue Nation The Imposter The man on the train Samson and Deliah The Master Iron Man 3 Shutter Insidious Paper Heart A Separation Argo Call Me Kuchu Finding Vivian Maier March of the Penguins The Descendants The Host Despicable Me Wendy and Lucy The One I Love The Matador Grabbers Bug The Best of Youth Amores Perros The king of Devil's Island Elite Squad Lincoln Precious The Host Chef Fill the Void The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel Ted Dead Snow Anger Management The Two Towers The Man Without a Past West of Memphis Bridge of Spies Hugo Moon Summer Hours The World's End Coherence Secretary Life Aquatic 17 Again The Ladykillers Pans Labyrinth The Crash Reel Volver Birdman Good Night and Good Luck Into the Wild Spy The World's End Rise of the Planets of the Apes Secretary Klown THem Quarantine Fellowship of the ring The Bourne Ultimatum Timbuktu Best of enemies Bowling for Columbine Headhunters Gomorra The Way, Way Back Hachi: A Dog's Tale Room 237 A.I. Passion of the christ Funny Games The Look of Silence The Beaches of Agness Shrek Adaptation Batman Begins Hairspray Enchanted The Skin I live IN Uncle Boonmee Chuck & Buck Taken Evil Dead antiviral Sherpa Selma Shaun of the Dead Saraband A Band called death Girlhood Blue Jasmine The Italian Spider Man American Psycho Old School Suicide Club The Ice Harvest Spotlight Mad Max: Fury Road Oslo. -

CMSI Journey to the Academy Awards -- Race and Gender in a Decade of Documentary 2008-2017 (2-20-17)

! Journey to the Academy Awards: A Decade of Race & Gender in Oscar-Shortlisted Documentaries (2008-2017) PRELIMINARY KEY FINDINGS Caty Borum Chattoo, Nesima Aberra, Michele Alexander, Chandler Green1 February 2017 In the Best Documentary Feature category of the Academy Awards, 2017 is a year of firsts. For the first time, four of the five Oscar-nominated documentary directors in the category are people of color (Roger Ross Williams, for Life, Animated; Ezra Edelman, for O.J.: Made in America; Ava DuVernay, for 13th; and Raoul Peck, for I Am Not Your Negro). In fact, 2017 reveals the largest percentage of Oscar-shortlisted documentary directors of color over at least the past decade. Almost a third (29%) of this year’s 17 credited Oscar-shortlisted documentary directors (in the Best Documentary Feature category) are people of color, up from 18 percent in 2016, none in 2015, and 17 percent in 2014. The percentage of recognized women documentary directors, while an increase from last year (24 percent of recognized shortlisted directors in 2017 are women, compared to 18 percent in 2016), remains at relatively the same low level of recognition over the past decade. In 2016, as a response to widespread criticism and negative media coverage, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences welcomed a record number of new members to become part of the voting class to bestow Academy Awards: 683 film professionals (46 percent women, 41 percent people of color) were invited in.2 According to the Academy, prior to this new 2016 class, its membership was 92 percent white and 75 percent male.3 To represent the documentary category, 42 new documentary creative professionals (directors and producers) were invited as new members. -

Sadegh-Vaziri Dissertation

IRANIAN DOCUMENTARY FILM CULTURE: CINEMA, SOCIETY, AND POWER 1997-2014 ____________________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ____________________________________________________________________________________ by Persheng Sadegh-Vaziri December 2015 Examining Committee Members: Patrick M. Murphy, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Roderick Coover, Film Media Arts Naomi Schiller, Anthropology & Archaeology, Brooklyn College Hamid Naficy, Radio-TV-Film, Northwestern University Nora M. Alter, External Member, Film Media Arts © Copyright 2015 by Persheng Sadegh-Vaziri All Rights Reserved ! ii! ABSTRACT Iranian documentary filmmakers negotiate their relationship with power centers every step of the way in order to open creative spaces and make films. This dissertation covers their professional activities and their films, with particular attention to 1997 to 2014, which has been a period of tremendous expansion. Despite the many restrictions on freedom of expression in Iran, especially between 2009 and 2013, after the uprising against dubious election practices, documentary filmmakers continued to organize, remained active, and produced films and distributed them. In this dissertation I explore how they engaged with different centers of power in order to create films that are relevant -

Stu's Movie Reviews 2013 Father's Day Edition

Stu's Movie Reviews 2013 Father’s Day Edition Note I’m definitely not a pro reviewer. It’s just that if I don’t jot down impressions of movies I watch, I tend to forget them in a week. I rarely see blockbusters, usually stick to films that gross less than 10 mil. As a joke, I started rating these movies to three significant figures sometime in 2011. That way I could say I was the most precise (if not accurate) movie reviewer in the world. I started to add rambling riffs at the end of reviews sometime in 2011 as well. Warning! The reviews have typos and weird sentences with Yiddish grammar galore. Ignore the typos but not the opinions. My Rules of Thumb If it isn't funny, it better be damn good (mediocre and funny is OK); if it has subtitles, it better be fantastic. What You’ll See Mentioned Time and Time Again The script is lousy, but the acting is excellent. A Modest Request You can disagree with me, but don’t shoot me. This Year I’ve Added Color Coding Red: Run, do not walk, to your library to get a copy. Orange: I like it. Black: If you’re sick at home with a fever and this thing shows up on TV, why not? Blue: Brain cell killer. 2 All Time Favorites This is a good way to see if it’s worthwhile to read my reviews. If you shake your head at the list below, go no further. American Splendor Drama Annie Hall Comedy Bananas Comedy Beaufort Foreign Being John Malkovich Comedy Best in Show Comedy Big Night Drama Bonnie and Clyde Drama Boys Don't Cry Drama Breaker Morant: Drama Capturing the Friedmans Documentary Chicken Run Comedy Chinatown