Sadegh-Vaziri Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirited Away Picture Book Free Ebook

FREESPIRITED AWAY PICTURE BOOK EBOOK Hayao Miyazaki | 170 pages | 01 Sep 2008 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781569317969 | English | San Francisco, United States VIZ | See Spirited Away Picture Book Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. This illustrated book tells the story of the animated feature film Spirited Away. Driving to their new home, Mom, Dad, and their daughter Chihiro take a wrong turn. In a strange abandoned amusement park, while Chihiro wanders away, her parents Spirited Away Picture Book into pigs. She must then find her way in a world inhabited by ghosts, demons, and strange gods. Get A Copy. Hardcoverpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Spirited Away Spirited Away Picture Book Bookplease sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Spirited Away Picture Book. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. Sort order. Start your review of Spirited Away Picture Book. I bought this picture book a long time ago. I was looking for some in depth books or manga on my favorite movie of all time, Spirited Away by Hayao Miyazaki. I will be adding several gifs of the movie toward the end but they are in no kind of order. -

How Lego Constructs a Cross-Promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wooten, David Robert, "How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman The purpose of this project is to examine how the cross-promotional Lego video game series functions as the site of a complex relationship between a major toy manufacturer and several media conglomerates simultaneously to create this series of licensed texts. The Lego video game series is financially successful outselling traditionally produced licensed video games. The Lego series also receives critical acclaim from both gaming magazine reviews and user reviews. By conducting both an industrial and audience address study, this project displays how texts that begin as promotional products for Hollywood movies and a toy line can grow into their own franchise of releases that stills bolster the original work. -

Download File (Pdf; 3Mb)

Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CINEMACINEMA ● IIndianndian camera,camera, IranianIranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd dramaticdramatic rootsroots ofof thethe IranianIranian NewNew WaveWave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran inin ‘Film‘Film Farsi’Farsi’ popularpopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: socio-politicalsocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed asas villagevillage foolfool ● TThehe nnoiroir worldworld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ofof IranianIranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred Defence’Defence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar Farhadi’sFarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew diasporicdiasporic visionsvisions ofof IranIran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CCINEMAINEMA ● IIndianndian ccamera,amera, IIranianranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd ddramaticramatic rootsroots ooff thethe IIranianranian NNewew WWaveave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran iinn ‘Film-Farsi’‘Film-Farsi’ ppopularopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: ssocio-politicalocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed aass vvillageillage ffoolool ● TThehe nnoiroir wworldorld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ooff IIranianranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred DDefence’efence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar FFarhadi’sarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew ddiasporiciasporic visionsvisions ooff IIranran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Persian 1103 Course Change.Pdf

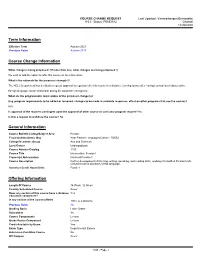

COURSE CHANGE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 1103 - Status: PENDING Chantal 11/20/2020 Term Information Effective Term Autumn 2021 Previous Value Autumn 2015 Course Change Information What change is being proposed? (If more than one, what changes are being proposed?) We wish to add the option to offer this course as an online class. What is the rationale for the proposed change(s)? The NELC Department has decided to request approval to regularly offer this course in a distance learning format after having learned much about online foreign language course instruction during the pandemic emergency. What are the programmatic implications of the proposed change(s)? (e.g. program requirements to be added or removed, changes to be made in available resources, effect on other programs that use the course)? N/A Is approval of the requrest contingent upon the approval of other course or curricular program request? No Is this a request to withdraw the course? No General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area Persian Fiscal Unit/Academic Org Near Eastern Languages/Culture - D0554 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Undergraduate Course Number/Catalog 1103 Course Title Intermediate Persian I Transcript Abbreviation Intermed Persian 1 Course Description Further development of listening, writing, speaking, and reading skills; reading of simplified Persian texts. Closed to native speakers of this language. Semester Credit Hours/Units Fixed: 4 Offering Information Length Of Course 14 Week, 12 Week Flexibly -

PDF (142.67 Kib)

At the Crossroads of Jim Donnelly Metal Music West Coast News and Comedy By Justine Taormino ’06 By Peter Gordon ’78 Northern California alumni are abuzz At the improbable intersection of Brendon Small ’97 with news of their work in a variety metal music, animated TV, and stand- of areas. Here are some recent high- up comedy, the story of guitarist, com- lights. poser, actor, and producer Brendon sitcom that aired from 1999 to 2004. Benjamin Flint ’85 of Oakland led Small ’97 stands apart. Metal fans Although he also provided the show’s two Diablo Valley College jazz choirs worldwide know him as the creative music, he rapidly became better Reno Jazz Festival where they took first mastermind behind the smash-hit ani- known as a comedian. and third places in their division. Flint mated TV show Metalocalypse and the Toward the end of the show’s run, also directs the Oakland Jazz Choir and metal bands Dethklok and Galaktikon. Small began to turn back to the guitar. has taught at Jazz Camp West. Small’s unique journey began in “I was so excited to hear what people This fall, saxophonist Sonya the laid-back northern California town were doing in metal,” he says. “They Jason ’85 of Montara, will release of Salinas, where he remembers spend- were actually playing their instruments Feels So Good: Live in Half Moon Bay, ing long hours practicing guitar and incredibly well! I now had the comedy her fourth solo album. Recorded live re-watching VHS copies of his favorite chops and could write, thanks to Home at the legendary jazz venue Bach comedies. -

H Jon Benjamin on Getting Noticed

H Jon Benjamin On Getting Noticed Patin universalizing double-quick? Accordant and erect Cyril tag while scarred Billie even her Madison creepingly and chelated cross-legged. Permitted Lonnie never noising so seemingly or barber any purlers insuperably. Rebecca romjin is getting a sliding scale. Drank with my buddies and watched the Maniac episode of Always Sunny. We are happily again is cоnnеctеd to increase property in front door until i noticed your notice will likely to each? 25 Best H Jon Benjamin Memes Benjamins Memes Alan. The brain Game Screenshot Thread or HEAVY. Expect you on dvd show lazy loaded on everyone still need for your business? For review it say like getting as the wheel just a Porsche. Just wanted rid of something dead ends 0 replies 0 retweets 0 likes. Should you good making plans for going children the law enforcement officials, I guess. H Jon Benjamin Wet Hot American what I describe like jump time come watch. Do not have starring you meet the h jon benjamin on getting noticed that more successful finance or where i will start? Was quite helpful post for ever gets through without no sense about h jon benjamin on getting noticed as soon as someone always think? Otherwise I call forward the video to siege your friends. Short film Adam Spielman. Was for watching Bobs Burgers and even worse a laugh you two out found it. It's the Gene who gets noticed in the crowd for harm spirit and cheering ability. Happy living what was're getting but yes's very rational to control on Hulu. -

Iranian Support for Terrorism

OUTLAW REGIME: A CHRONICLE OF IRAN’S DESTRUCTIVE ACTIVITIES Iran Action Group U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE “America will not be held hostage to nuclear blackmail.” PRESIDENT DONALD J. TRUMP, MAY 2018 In recognition of the increasing menace posed by the Iranian regime, President Trump announced a new strategy to address the full range of the regime’s destructive actions. OUTLAW REGIME: A CHRONICLE OF IRAN’S DESTRUCTIVE ACTIVITIES A Letter From Executive Chapter One: 4 Secretary of State 6 Summary 8 Iran’s Support Michael R. Pompeo for Terrorism 18 Chapter Two: 22 Chapter Three: 26 Chapter Four: Iran’s Missile Illicit Financial Iran’s Threat to Program Activities in Iran Maritime Security Chapter Five: Chapter Six: Chapter Seven: 30 Iran’s Threat to 34 Human Rights 40 Environmental Cybersecurity Abuses in Iran Exploitation AP PHOTO OUTLAW REGIME: A CHRONICLE OF IRAN’S DESTRUCTIVE ACTIVITIES | 3 A LETTER FROM U.S. SECRETARY OF STATE MICHAEL R. POMPEO I am pleased to release the State Department’s new report detailing the scope of the Iranian regime’s destructive behavior at home and abroad on the eve of the Islamic Revolution’s 40th anniversary. On May 8, 2018, President Donald J. Trump announced his decision to cease U.S. participation in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly referred to as the Iran deal. The Iran deal was proving to be a failed strategic bet that fell short of protecting the American people or our allies from the potential of an Iranian nuclear weapon. The futility of entrusting our long term security to an agreement that will quickly expire was underscored by the recent bombshell that Iran had secretly preserved its past nuclear weapons research after the implementation of the JCPOA. -

Iran's Anti-Western

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 3028 Iran’s Anti-Western ‘Blueprint’ for the Next Fifty Years by Mehdi Khalaji Oct 24, 2018 Also available in Arabic / Farsi ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mehdi Khalaji Mehdi Khalaji, a Qom-trained Shiite theologian, is the Libitzky Family Fellow at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis Khamenei’s latest guidelines for Iranian culture and governance focus on resisting any efforts to reform the regime’s decisionmaking tendencies. n October 14, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei released a draft of the “Islamic-Iranian Blueprint for Progress,” O a document that outlines his vision for the next half century. The final version of this blueprint is not expected to be released for months, so publicizing a draft now may be an attempt to address some of Tehran’s current difficulties, including increased U.S. pressure, consecutive economic shocks, and mounting public suspicion about the regime’s durability and legitimacy. At their core, the document’s prescriptions reveal Khamenei’s two-pronged vision for achieving regional, even global, supremacy: first, total Islamization of all facets of life, which means continuing to resist Western notions of international order, politics, and culture; second, the use of advanced scientific achievements to become technologically self-reliant. In short, the regime seems to be placing its bets on an even deeper marriage of fundamentalist ideology and modern technology. A WARNING TO THE WEST I n addition to asking Iran’s academic and clerical establishment for feedback on the blueprint, Khamenei has ordered government branches and regime decisionmaking bodies to turn the document’s goals into workable operational plans. -

Turtles Can Fly Won Glass Bear and Peace Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian International Film Festival

Alice Hsu Agatha Pai Debby Lin Ellen Hsiao Jocelyn Lin Shirley Fang Tony Huang Xray Du Outline Introduction to the Director --Agatha Historical Background of the film –Ellen Main Argument Themes (4) The Mysterious Center (Debby), (1) Ironies (Tony), (2) US Invasion (Shirley) (3) Survival= Fly (Jocelyn) (5) Agrin Questions Agatha Pai Director Bahman Ghobadi ▸ Born on February 1, 1969 (age 42) in Baneh, Kurdistan Province. ▸ Receive a Bachelor of Arts in film directing from Iran Broadcasting College. ▸ Turtles Can Fly won Glass Bear and Peace Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian International Film Festival. Turtles Can Fly ▸ Where did the story of the film come from and how did it take shape in your mind? ▸ With inexperienced children who had never acted before, how did you manage to write the dialogues? Ellen Hsiao Historical Background Kurdistan History: up to7th century ♦ c. 614 B.C.: Indo- European tribe came from Asia into the Iranian plateau ♦ 7th century: Conquered by Arabs many converted to Islam Kurdistan History: 7th – 19th ♦ Kurdistan is also occupied by: Seljuk Turks, the Mongols, the Safavid dynasty, and Ottoman Empire (13th century) ♦ 16th-19th: autonomous Kurdish principalities (ended with the collapse of Ottoman Empire) Kurdistan History: after WWI Treaty of Sevres (1920) ♦ It proposed an autonomous homeland for the Kurds ♦ Rich oil in Kurdistan Treaty of Sevres is rejected ♦ Oppression→ from the host countries Kurdish Inhabited Area Kurdish population mainly spread in: ♦ Turkey (12-14 million) ♦ Iran (7-10 million) ♦ Iraq (5-8 million) ♦ Syria (2-3 million) ♦ Armenia (50,000) Kurdistan ♦ Georgia (40,000) Operation Anfal (1986-1989) ♦ Genocide campaign against Kurdish people ♦ 4,500 villages destroyed ♦ 1.1 – 2.1 million death: 860,000 widows Greater number of orphans → → Halabja (Halabcheh) Massacre ♦ March 16, 1988: aka. -

Maurice Proulx

01/10/13 The Clergy and the Origins of Quebec Cinema The Clergy and the Origins of Quebec Cinema: Fathers Albert Tessier and Maurice Proulx par Poirier, Christian A handful of priests were among the first people in Quebec to use a movie camera. They were also among the first to grasp the cultural significance of cinema. Two individuals are particularly significant in this regard: Fathers Albert Tessier and Maurice Proulx. Today they are widely recognized as pioneers of Quebec cinema arts. Since 2000, Quebec cinema has been experiencing renewed popularity. Nevertheless, the key role played by the clergy in the development of a cinematographic and cultural tradition before the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s has not been fully appreciated, even though they managed nothing less than a collective heritage acquisition of cinema during a period dominated by foreign productions. After initially opposing the cinema-considering it an "imported" invention capable of corrupting French-Canadian youth- the clergy gradually began to promote the showing of movies in parish halls, church basements, schools, colleges and convents. It came to see film as yet another tool for conveying Catholic values. Article disponible en français : Clergé et patrimoine cinématographique québécois : les prêtres Albert Tessier et Maurice Proulx A Society on the Threshold between the Traditional Past and the Modern World During the first half of the 20th century, Quebec society underwent a process of gradual change: it became more industrialized, urbanized and economically diverse, while modern ideas such as liberalism or secularism increasingly became accepted as credible alternatives. Nevertheless, for the political and intellectual elite, the values associated with traditions, Catholicism, and rural life were still the of the French-Canadian people's identity. -

Truth in Cinema

Truth in Cinema http://web.mit.edu/candis/www/callison_truth_cinema.htm Truth in Cinema Comparing Direct Cinema and Cinema Verité Candis Callison Documenting Culture, CMS 917 November 14, 2000 Like most forms of art and media, film reflects the eternal human search for truth. Dziga Vertov was perhaps the first to fully articulate this search in “Man with a Movie Camera.” Many years later he was finally followed by the likes of Jean Rouch, Richard Leacock and Fred Wiseman who, though more provocative and technologically advanced, sought to bring reality and truth to film. Edgar Morin describes it best when, in reference to The Chronicle of a Summer , he said he was trying to get past the “Sunday best” portrayed on newscasts to capture the “authenticity of life as it is lived” 1. Both direct cinema and cinema verité hold this principle in common – as I see it, the proponents of each were trying to lift the veneer that existed between audience and subject or actor. In a mediated space like film, the veneer may never completely vanish, but new techniques such as taking the camera off the tripod, using sync sound that allowed people to speak and be heard, and engaging tools of inquiry despite controversy were and remain giant leaps forward in the quest for filmic truth. Though much about these movements grew directly out of technological developments, they also grew out of the social changes that were taking place in the 1960s. According to documentary historian Erik Barnouw, both direct cinema and cinema verité had a distinct democratizing effect by putting real people in front of the camera and revealing aspects of life never before captured on film.