Driving, Cities and Changing Climates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NSW Sydney Moorings Analysis

NSW Sydney Moorings Analysis Sydney Harbour (Area A) Date Last Mooring Total No. of No. of Private Applicant Mooring Bay Code/Bay Name Allocated & Ratio Applicants Moorings Totals Totals Comments AA - DARLING POINT 4 5/06/2015 25 AC - DOUBLE BAY 31 21/05/2015 203 AD - ELIZABETH BAY 32 9/04/2015 20 AE - FELIX BAY 11 30/03/2015 39 AF - HERMIT BAY 8 31/05/2015 30 AJ - PARSLEY BAY 13 28/05/2015 44 AO - ROSE BAY 40 2/06/2015 138 AP - RUSHCUTTERS BAY 58 27/04/2015 75 AT - VAUCLUSE BAY 25 28/05/2015 72 34% AU - WATSONS BAY 45 5/03/2015 131 267 777 Sydney Harbour (Area B) BB - BEAUTY POINT 0 8/05/2014 17 BE - CASTLECRAG 5 12/05/2015 45 BN - KILLARNEY 14 2/06/2015 68 BP - LONG BAY 5 29/04/2015 86 BR - NORTHBRIDGE 0 23/03/2015 52 BS - PEARL BAY 1 19/05/2015 145 BT - PICKERING POINT 0 7/05/2015 56 BU - POWDER HULK BAY 6 25/05/2015 105 BV - QUAKERS HAT BAY 0 12/06/2015 93 BX - SAILORS BAY 12 8/04/2015 62 BY - SALT PAN CREEK 3 7/05/2015 25 CA - SEAFORTH 0 28/05/2015 56 CD - SUGARLOAF BAY 1 29/04/2015 26 CE - SUGARLOAF POINT 8 7/02/2015 28 7% CH - WILLOUGHBY BAY 5 10/09/2014 32 60 896 Sydney Harbour (Area C) AG - LITTLE MANLY COVE 24 6/05/2015 35 AH - MANLY COVE 52 30/01/2015 86 AI - NORTH HARBOUR 106 1/04/2015 111 BA - BALMORAL 36 2/12/2014 56 BL - FISHER BAY 15 16/02/2015 18 BZ - SANDY BAY 22 17/02/2014 24 GE - CAREENING COVE 27 9/02/2009 18 GL - KIRRIBILLI 8 19/08/1992 2 GN - LITTLE SIRIUS COVE 10 9/04/2015 80 GP - MOSMAN BAY 48 29/01/2015 90 GQ - NEUTRAL BAY 50 6/01/2015 47 GU - SHELL COVE 30 2/06/2015 74 65% GW - TAYLORS BAY 0 28/05/2015 21 428 -

Terms and Conditions Central and Southern

Terms and Conditions: NSW SunSmart Primary School Program Marquee Competition 1. Information on how to enter and prizes form part of these conditions of entry. 2. It is assumed all entrants have read the Terms and Conditions prior to entering. 3. The competition is known as the NSW SunSmart Primary School Program Marquee Competition. 4. Entry is open to all eligible non SunSmart NSW primary schools that join the SunSmart Primary School Program from 8 October 2012 and are classified as a SunSmart School before 5pm AEST on 21 December 2012. Eligible schools include: Abbotsford Public School Auburn Campus of Sydney Adventist College Bellimbopinni Public School Abbotsleigh Auburn North Public School Belmont Christian College Adaminaby Public School Auburn Public School Belmore North Public School Aetaomah School Auburn West Public School Belrose Public School Al Noori Muslim School Austral Public School Bendemeer Public School Al Sadiq College Australia Street Infants School Bendick Murrell Public School Al Zahra College Australian International Academy, Sydney Bennett Road Public School Albury North Public School Avalon Public School Berala Public School Albury Public School Balgowlah Heights Public School Beresford Road Public School Albury West Public School Balgowlah North Public School Berkeley Public School Alexandria Park Community School Balgownie Public School Berkeley Vale Public School Alfords Point Public School Balmain Public School Berowra Christian Community School All Hallows Primary School Five Dock Balranald Central School -

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012-2017: Metro North East

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17: Metro North East Region A new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours © Copyright State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the Office of Environment and Heritage and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is part of the Office of Environment and Heritage. Throughout this strategy, references to NPWS should be taken to mean NPWS carrying out functions on behalf of the Director General of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, and the Minister for the Environment. For further information contact: Metro North East Region Metropolitan and Mountains Branch National Parks and Wildlife Service Office of Environment and Heritage PO Box 3031 Asquith NSW 2077 Phone: (02) 9457 8900 Report pollution and environmental incidents Environment Line: 131 555 (NSW only) or [email protected] See also www.environment.nsw.gov.au/pollution Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South, NSW 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks, climate change and energy efficiency information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978 1 74293 625 3 OEH 2012/0374 August 2013 This plan may be cited as: OEH 2012, Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17, Metro North East Region: a new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney. -

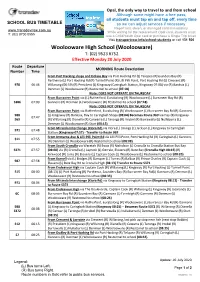

BUS TIMETABLE So We Can Adjust Services If Necessary

Opal, the only way to travel to and from school Although some might have a free pass, all students must tap on and tap off, every time SCHOOL BUS TIMETABLE so we can adjust services if necessary. Report lost, stolen, or damaged card immediately. www.transdevnsw.com.au While waiting for the replacement Opal card, students must T: (02) 8700 0555 use a Child/Youth Opal card or purchase a Single Trip ticket. Visit transportnsw.info/school-students or call 131 500 Woolooware High School (Woolooware) T: (02) 9523 6752 Effective Monday 20 July 2020 Route Departure MORNING Route Description Number Time From Port Hacking shops and Dolans Bay via Port Hacking Rd (L) Telopea (R)Saunders Bay (R) Parthenia (L) Port Hacking Rd (R) Turriell Point (R) Lilli Pilli Point, Port Hacking Rd (L) Crescent (R) 978 06:46 Willarong (06:59) (R) President (L) Kingsway (Caringbah Station, Kingsway 07:08) via (R) Banksia (L) Denman (L) Woolooware (R) Restormel to school (07:18) Note: DOES NOT OPERATE ON THURSDAY From Burraneer Point via (L) Rutherford, Eurabalong (R) Woolooware (L) Burraneer Bay Rd (R) S386 07:00 Gannons (R) Denman (L) Woolooware (R) Restormel to school (07:18) Note: DOES NOT OPERATE ON THURSDAY From Burraneer Point via Rutherford, Eurabalong (R) Woolooware (L) Burraneer Bay Rd (R) Gannons 988 (L) Kingsway (R) Banksia, Hay to Caringbah Shops (08:04) Becomes Route 969 via Hay (R) Kingsway 07:47 969 (R) Willarong (R) Dianella (R) Carwarra (L) Taronga (R) Irrubel (R) Burrawalla (L) Nullaburra (L) Denman (L) Woolooware (R) Sturt (08:15) From Miranda Interchange -

STRANDED! Port Stephens Unit’S Rocky Rescue Big Boat Spend $2.5 Million Vessel Upgrade Meet the Fleet Kevlacat 3000 Series

Volunteers saving lives on the water Quarterly Journal of Marine Rescue NSW | Issue 11, June 2012 STRANDED! Port Stephens unit’s rocky rescue Big boat spend $2.5 million vessel upgrade Meet the fleet Kevlacat 3000 series PLUS: Emergency Services Medal winners | High-tech gadgets | 4-page local guide CONTENTS Issue 11 | June 2012 FROM THE HELM 2 Commissioner’s report 4 Chairman’s report ON THE RADAR Quarterly Journal of Marine Rescue NSW 2-3 • Volunteer Education Scholarship • Queen’s Birthday honours 4-5 • MRNSW on show at SIBS • $2.5 million fleet upgrade Publisher Marine Rescue NSW 7 • Crackdown on illegal fishing Level 5, 9-13 Young Street 8 • Port Hacking UC earns seniors award Sydney NSW 2000 • New Council a voice for volunteers • Five units receive $110,000 in grants Contact Kate Woods, Ken McManus IN THEIR OWN WORDS Phone: 02 8071 4848 11 Hawkesbury unit skipper Catherine Sky Fax: 02 9969 5214 Email: [email protected] MAKING WAVES Editor 14-15 Northern Rivers news Ashley Gray • Wooli • Brunswick • Cape Byron 16-17 Mid North Coast news Design and Layout • Coffs Harbour • Forster-Tuncurry Nicole Brown • Port Macquarie Advertising 18, 23-25 Hunter Valley / Central Coast news Graham Joss • Central Coast • The Entrance • Port Stephens Email: [email protected] • Newcastle • Lake Macquarie Phone: 0419 492 836 26-28 Greater Sydney news • Port Jackson • Broken Bay Printing • Port Hacking • Hawkesbury Printing, binding and mailing by Galloping Press Pty Ltd Unit 29/398 The Boulevarde, Kirrawee NSW 2232 29-31 Illawarra news • Jervis Bay • Port Kembla • Shellharbour Marine Rescue NSW is pleased to acknowledge the invaluable support of our • Ulladulla • Shoalhaven Soundings advertisers. -

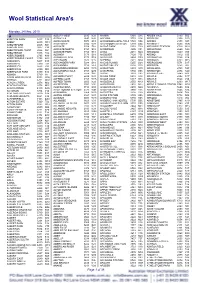

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

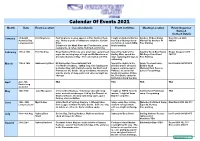

Calendar of Events 2021

Calendar Of Events 2021 Month Date Event Location Location Details Event Activities Meeting Location Event Organiser Name & Contact Details January 23rd-26th Port Stephens Port Stephens located approx. 2.5hrs North of Syd- 1 night on Dalbora Marina, Soldiers Pt Boat Ramp David Creed 0428 Australia Day ney. Home to pods of bottlenose dolphins, Karuah bus trip to Murrays brew- Mitchell St, Soldiers Pt 688024 Long weekend River, ery for lunch, beach BBQ, Free Parking Entrance to the Myall River and Tea Gardens, great koala spotting restaurants, & cafes, walks, fishing & swimming February 13th & 14th Port Hacking Royal National Park one end, quiet river system lead- Spend the night at the Swallow Rock Boat Ramp Roger Gregson 0410 ing to the exciting bays of high end McMansions at Audley Weir, spend the Off Grays Point Road 582133 Cronulla, Burraneer Bay . The sand spit at Lilli Pilli. days exploring the bays & Free Parking swimming March 13th & 14th Hawkesbury River Mt Kuring-Gai Chase National Park Spend the nights in the Apple Tree boat ramp, Ian Franklin 041239475 1 hr North of Sydney. 120km long river leading out pristine waters of Castle Bobbin Head to Broken Bay, with Central coast to the North and Lagoon, venture over to (National Park Pass re- Pittwater to the South. Steep sandstone mountains Pittwater to anchor for quired. For parking). provide plenty of deep water and safe overnight an- lunch and explore Pittwa- chorage. ter, The Basin, exclusive townships along the way. April 2nd - 5th TBA TBA TBA TBA Easter long weekend May 14th -16th Lake Macquarie 2 hrs north of Sydney. -

Beachwatch Monthly Reports

Beachwatch monthly reports Beachwatch monthly reports provide a snapshot of bacterial levels in the previous month as well as information on rainfall and pollution incidents, such as sewage overflows and sewage treatment plant bypasses. The latest reports are available for: • Northern Sydney beaches - covers the ocean beaches from Palm Beach to Shelly Beach (Manly), and harbour beaches in Pittwater and North Harbour • Sydney Central Beaches - covers the ocean beaches from Bondi to Malabar, and harbour beaches in Middle Harbour, lower Lane Cove River, lower Parramatta River and Port Jackson • Sydney Southern Beaches - covers the ocean beaches in the Sutherland Shire, and harbour beaches in Botany Bay, lower Georges River and Port Hacking Northern Sydney Beaches Water Quality during March 2012 Despite heavy rain, the water quality at Sydney's northern beaches was generally good during March, with 24 of the 35 beaches suitable for swimming on all sampling occasions. The best performing beaches were: • Pittwater: Clareville Beach, North Scotland Island, South Scotland Island, Elvina Bay, Bayview Baths and The Basin • Ocean beaches: Palm, Whale, Avalon, Bilgola, Newport, Bungan, Mona Vale, Turimetta, North Narrabeen, Collaroy, Dee Why, North Curl Curl, South Curl Curl, Freshwater, North Steyne, and Shelly (Manly) • North Harbour: Forty Baskets Pool and Manly Cove. Enterococci levels exceeded the safe swimming limit of 40 cfu/100mL in one of the five samples at the following locations: • Pittwater: Paradise Beach Baths, Taylors Point Baths and Great Mackerel Beach • Ocean beaches: Warriewood, Long Reef, Queenscliff and South Steyne • Lagoon: Birdwood Park (Narrabeen Lagoon) • North Harbour: Fairlight Beach and Little Manly Cove. -

Flipbook of Marine Boating Upgrade Projects

BETTER BOATING N S W MARITIME IN FRAS TRUC TURE G R A N T S Rose Bay, Sydney Harbour, NSW, includes Better Boating Program projects to improve dinghy storage, boat ramp access and car/trailer parking. Photo: Andrea Francolini.. Sample text for the purpose of the layout sample of text for the Contents purpose of the layout sample of text for e of the layout sample of text for the purposeNorth of the Coast layout. 06 Hunter / Inland 14 Sample text for the purposeHawkesbury of the layout / Broken sample Bay of text22 for the purpose of the layoutSydney sample Region of text for the purf the28 layout sample of text for the purposeSydney Harbourof the layout. 34 South Coast 42 Sample text for the purposeMurray of / theSouthern layout Tablelands f text for the 48 purpose of the. Layout sample ofProject text for Summary the purpose of the layout54 sample of text for the purpose of the layout. INTRODUCTION NSW Maritime is committed to serving the boating community. One key area where that commitment is being delivered is infrastructure. For more than 10 years, New South Wales Maritime has delivered improved boating facilities statewide under a grants initiative now titled the Better Boating Program. This program started in 1998 and has since provided more than $25 million in grants to fund more than 470 boating facility projects across NSW. From small works like upgraded dinghy storage racks to large boat launching facilities with dual access ramps, pontoons and car/trailer parking, NSW Maritime is working with partners such as councils to fund dozens of projects every year. -

Our Lady of Fatima, Caringbah T: 9524 9980

Opal, the only way to travel to and from school Although some might have a free pass, all students must tap on and tap off, every time SCHOOL BUS TIMETABLE so we can adjust services if necessary. Report lost, stolen, or damaged card immediately. www.transdevnsw.com.au While waiting for the replacement Opal card, students must T: (02) 8700 0555 use a Child/Youth Opal card or purchase a Single Trip ticket. Visit transportnsw.info/school-students or call 131 500 Our Lady Of Fatima, Caringbah T: 9524 9980 Route Departure MORNING Route Description Number Time 968 07:13 From Bonnet Bay via Jannali Station (West Side 07:25) via Route 968 (Green Point 07:32) (Oyster Bay Shops 07:42) (R) Oyster Bay (L) Georges River (L) Carvers, Bates (L) Box, Freya (L) Siandra around Kareela loop (07:46) then via Box (L) Bandain (L) Garnet (R) Marshall(R) The Boulevarde (L) Bath (L) Waratah (R) Highway (L) Kingsway (R) Kiora (Miranda Interchange) via Kiora (L) Urunga (L) Jackson (L) Kingsway (R) Kiora (R) The Boulevarde (R) Willarong (L) Kingsway (R) President to school (President Ave) (08:15) 971 07:27 From South Cronulla (Shelly Park) via Waratah (R) Ewos (R) Nicholson (L) Cronulla to Cronulla Station (Station Side 07:36) Transfer to Bus 971 to Caringbah (Dep 07:41) (L) Cronulla, Croydon, Purley (L) Searl (L) Burraneer Bay Rd (R) Gannons (L) Kingsway to Caringbah Station (Kingsway 07:54) 988 07:47 From Burraneer Point via route 988 via Rutherford, Eurabalong (R) Woolooware (L) Burraneer Bay Rd (R) Gannons (L) Kingsway (R) Banksia, Hay to Caringbah Shops (Hay -

Walks, Paddles and Bike Rides in the Illawarra and Environs

WALKS, PADDLES AND BIKE RIDES IN THE ILLAWARRA AND ENVIRONS Mt Carrialoo (Photo by P. Bique) December 2012 CONTENTS Activity Area Page Walks Wollongong and Illawarra Escarpment …………………………………… 5 Macquarie Pass National Park ……………………………………………. 9 Barren Grounds, Budderoo Plateau, Carrington Falls ………………….. 9 Shoalhaven Area…..……………………………………………………….. 9 Bungonia National Park …………………………………………………….. 10 Morton National Park ……………………………………………………….. 11 Budawang National Park …………………………………………………… 12 Royal National Park ………………………………………………………… 12 Heathcote National Park …………………………………………………… 15 Southern Highlands …………………………………………………………. 16 Blue Mountains ……………………………………………………………… 17 Sydney and Campbelltown ………………………………………………… 18 Paddles …………………………………………………………………………………. 22 Bike Rides …………………………………………………………………………………. 25 Note This booklet is a compilation of walks, paddles, bike rides and holidays organised by the WEA Illawarra Ramblers Club over the last several years. The activities are only briefly described. More detailed information can be sourced through the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, various Councils, books, pamphlets, maps and the Internet. WEA Illawarra Ramblers Club 2 October 2012 WEA ILLAWARRA RAMBLERS CLUB Summary of Information for Members (For a complete copy of the “Information for Members” booklet, please contact the Secretary ) Participation in Activities If you wish to participate in an activity indicated as “Registration Essential”, contact the leader at least two days prior. If you find that you are unable to attend please advise the leader immediately as another member may be able to take your place. Before inviting a friend to accompany you, you must obtain the leader’s permission. Arrive at the meeting place at least 10 minutes before the starting time so that you can sign the Activity Register and be advised of any special instructions, hazards or difficulties. Leaders will not delay the start for latecomers. -

OLMC Burraneer.Pdf

T: (02) 8700 0555 www transdevnsw.com.au SCHOOL SPECIAL BUS SERVICES Our Lady of Mercy College T: 9544 1966 BUS NO. TIME MORNING BUS ROUTE From Westfield Miranda Kiora Road Stand 3 via Kiora (L) Kingsway 971 07:48 (Caringbah Station 07:57) (R) Gannons (L) Burraneer Bay (R) Craig (L) Dominic to School (08:02) From South Cronulla via Waratah (R) Ewos (R) Nicholson (L) Cronulla (Cronulla Station 971 08:01 08:09) Cronulla, Croydon, Purley (L) Searl (L) Burraneer Bay (L) Bonnieview (R) Dominic to School (08:15) From Caringbah Station via Hay (R) Kingsway (R) Willarong (R) Dianella (R) Cawarra (L) Taronga (R) Irrubel (R) Burrawalla (L) Nullaburra (L) Denman (L) Woolooware 969 (R) Sturt (R) Franklin (L) Flinders (L) Kurnell (R) Ocean (L) Wyanbah (R) Hume 08:04 988 (L) Elouera (R) Bate Bay (R) Kirkwood (R) Links (L) Eloura, Gerrale (R) Laycock (R) Cronulla (Cronulla Station 08:24) Bus changes to route 988 via Cronulla, Croydon, Purley (L) Searl (L) Burraneer Bay Rd (L) Woolooware (R) Dominic to School (08:34) From Westfield Miranda Kiora Road Stand 3 via Kiora (L) Kingsway 971 08:04 (Caringbah Station 08:13) (R) Gannons (L) Burraneer Bay (R) Craig (L) Dominic (R) Willaburra (R) Dolans to School (08:21) BUS NO. TIME AFTERNOON BUS ROUTE S381 14:55 To Miranda via Dolans (L) Kingsway (Caringbah Station 15:00) to Kiora Rd (15:03) To Miranda Station via Dolans (L) Burraneer Bay (R) Gannons (L) Kingsway (L) Jackson S382 14:55 (R) Urunga to Station (15:10) To Cronulla Station via Dolans (R) Dominic (L) Woolooware (R) Burraneer Bay (R) Searl S383 14:55