Lola and Bilidikid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special

Princeton Garden Theatre Previews93G SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 2015 Benedict Cumberbatch in rehearsal for HAMLET INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS P RINCETONG ARDENT HEATRE.ORG 609 279 1999 Welcome to the nonprofit Princeton Garden Theatre The Garden Theatre is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Our management team. ADMISSION Nonprofit Renew Theaters joined the Princeton community as the new operator of the Garden Theatre in July of 2014. We General ............................................................$11.00 also run three golden-age movie theaters in Pennsylvania – the Members ...........................................................$6.00 County Theater in Doylestown, the Ambler Theater in Ambler, and Seniors (62+) & University Staff .........................$9.00 the Hiway Theater in Jenkintown. We are committed to excellent Students . ..........................................................$8.00 programming and to meaningful community outreach. Matinees Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 How can you support Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$8.00 the Garden Theatre? PRINCETON GARDEN THEATRE Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$7.00 Be a member. MEMBER Affiliated Theater Members* .............................$6.00 Become a member of the non- MEMBER You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. profit Garden Theatre and show The above ticket prices are subject to change. your support for good films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a membership form or join online. Your financial support is tax-deductible. *Affiliated Theater Members Be a sponsor. All members of our theater are entitled to members tickets at all Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange “Renew Theaters” (Ambler, County, Garden, and Hiway), as well for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety as at participating “Art House Theaters” nationwide. -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

OUT of the PAST Teachers’Guide

OUT OF THE PAST Teachers’Guide A publication of GLSEN, the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network Page 1 Out of the Past Teachers’ Guide Table of Contents Why LGBT History? 2 Goals and Objectives 3 Why Out of the Past? 3 Using Out of the Past 4 Historical Segments of Out of the Past: Michael Wigglesworth 7 Sarah Orne Jewett 10 Henry Gerber 12 Bayard Rustin 15 Barbara Gittings 18 Kelli Peterson 21 OTP Glossary 24 Bibliography 25 Out of the Past Honors and Awards 26 ©1999 GLSEN Page 2 Out of the Past Teachers’ Guide Why LGBT History? It is commonly thought that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered (LGBT) history is only for LGBT people. This is a false assumption. In out current age of a continually expanding communication network, a given individual will inevitably e interacting with thousands of people, many of them of other nationalities, of other races, and many of them LGBT. Thus, it is crucial for all people to understand the past and possible contributions of all others. There is no room in our society for bigotry, for prejudiced views, or for the simple omission of any group from public knowledge. In acknowledging LGBT history, one teaches respect for all people, regardless of race, gender, nationality, or sexual orientation. By recognizing the accomplishments of LGBT people in our common history, we are also recognizing that LGBT history affects all of us. The people presented here are not amazing because they are LGBT, but because they accomplished great feats of intellect and action. These accomplishments are amplified when we consider the amount of energy these people were required to expend fighting for recognition in a society which refused to accept their contributions because of their sexuality, or fighting their own fear and self-condemnation, as in the case of Michael Wigglesworth and countless others. -

Olive Films Presents

Mongrel Media Presents WHEN WE LEAVE A Film by Feo Aladag (118min., German, 2011) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Cast Umay ….SIBEL KEKILLI Kader (Umay’s father) ….SETTAR TANRIÖGEN Halime (Umay’s mother) ….DERYA ALABORA Stipe (Umay’s colleague) ….FLORIAN LUKAS Mehmet(Umay’s older brother) ….TAMER YIGIT Acar (Umay’s younger brother) ….SERHAD CAN Rana (Umay’s younger sister) ….ALMILA BAGRIACIK Atife (Umay’s best friend) ….ALWARA HÖFELS Gül (Umay’s boss) ….NURSEL KÖSE Cem (Umay’s son) ….NIZAM SCHILLER Kemal (Umay’s husband) ….UFUK BAYRAKTAR Duran (Rana’s fiancé) ….MARLON PULAT Crew Script & Direction ….FEO ALADAG Producers ….FEO ALADAG, ZÜLI ALADAG Casting ….ULRIKE MÜLLER, HARIKA UYGUR, LUCY LENNOX Director of Photography ….JUDITH KAUFMANN Editor ….ANDREA MERTENS Production Design ….SILKE BUHR Costume Design ….GIOIA RASPÉ Sound ….JÖRG KIDROWSKI Score ….MAX RICHTER, STÉPHANE MOUCHA Make-up MONIKA MÜNNICH, MINA GHORAISHI Germany, 2010 Length: 119 minutes Format: CinemaScope 1:2.35 Sound system: Dolby Digital In German and in Turkish with English subtitles Synopsis What would you sacrifice for your family’s love? Your values? Your freedom? Your life? German-born Umay flees from her oppressive marriage in Istanbul, taking her young son Cem with her. She hopes to find a better life with her family in Berlin, but her unexpected arrival creates intense conflict. -

Kebab Connection

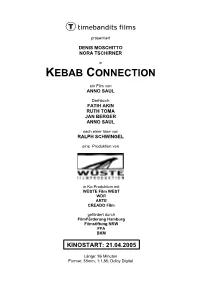

präsentiert DENIS MOSCHITTO NORA TSCHIRNER in KEBAB CONNECTION ein Film von ANNO SAUL Drehbuch FATIH AKIN RUTH TOMA JAN BERGER ANNO SAUL nach einer Idee von RALPH SCHWINGEL eine Produktion von in Ko-Produktion mit WÜSTE Film WEST WDR ARTE CREADO Film gefördert durch FilmFörderung Hamburg Filmstiftung NRW FFA BKM KINOSTART: 21.04.2005 Länge: 96 Minuten Format: 35mm, 1:1,85; Dolby Digital KEBAB CONNECTION VERLEIH timebandits films GmbH Stubenrauchstraße 2 14482 Potsdam Tel.: 0331 70 44 50 Fax.: 0331 70 44 529 [email protected] PRESSEBETREUUNG boxfish films Graf Rudolph Steiner GbR Senefelderstrasse 22 10437 Berlin Tel: 030 / 44044 751 Fax: 030 / 44044 691 E-mail: [email protected] Die offizielle Website des Films lautet: www.kebabconnection.de Weiteres Pressematerial steht online für Sie bereit unter: www.boxfish-films.de Seite 2 von 30 KEBAB CONNECTION INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Besetzung / Stab .......................................................................................4 Kurzinhalt / Pressenotiz.............................................................................5 Langinhalt..................................................................................................6 Produktionsnotizen ....................................................................................8 Interview mit Anno Saul.............................................................................11 Interview mit Nora Tschirner......................................................................14 Interview mit Denis Moschitto....................................................................16 -

Die Mechanik Der Erregung

Kultur SHOWGESCHÄFT Die Mechanik der Erregung Der inszenierte Wirbel um die Porno-Vergangenheit Sibel Kekillis, der deutschtürkischen Hauptdarstellerin im Berlinale-Siegerfilm „Gegen die Wand“, enthüllt vor allem eines: So freizügig sich eine Gesellschaft auch gibt – pseudoprüde Empörung zieht immer noch. KERSTIN STELTER / WÜSTE FILM / WÜSTE STELTER KERSTIN „Gegen die Wand“-Darsteller Ünel, Kekilli: Verschwitzte Enthüllungsarbeit nach dem Jubel über den Festivaltriumph uf der ersten Seite von „Bild“ bietet Hilfe an), tapfere Sibel (Wir sind stolz prangte am vergangenen Mittwoch auf sie) – das Blatt deklinierte den Fall nach AUschi Glas, 59, das sorgenfaltige allen Regeln des Boulevards durch. Reh. „Uschi Glas steht sündiger Film-Diva Dank der Enthüllung zog Kekilli, 23, in mutig bei“, lautete die Zeile. der Woche nach dem Triumph des „Gegen Heilige Uschi, da kam sie tatsächlich auf die Wand“-Melodrams bei der Berlinale- die Frontpage gewackelt, die Frau Sünde, Preisverleihung so viel Interesse auf sich, die „Bösartigkeit der menschlichen Natur“ dass der Regisseur des Films, der Ham- (Immanuel Kant). Ein anderes Wild, die burger Fatih Akin, neben der in Heilbronn rehäugige Sibel Kekilli, Hauptdarstellerin aufgewachsenen Jungschauspielerin nur des mit dem Goldenen Berlinale-Bären aus- noch eine Nebenrolle zu spielen schien. gezeichneten deutschen Films „Gegen die „Warum drehte die zarte Diva so harte Wand“, war auf dem Porno-Lotterlager er- Pornos?“, lautete die fürsorglich-kultur- wischt worden – „Bild“ fuhr seine neueste kritische Schlüsselfrage der „Bild“-Kam- Kampagne: Schlimme Sibel (Wie kann sie uns so täuschen), arme Sibel (Die Eltern „Bild“-Zeitung vom 17. Februar (Ausriss) verstoßen sie), hilfsbedürftige Sibel (Uschi Schlimme Sibel, arme Sibel 160 der spiegel 9/2004 pagne. -

Accion Mutante

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Salford Institutional Repository “Esto no es un juego, es Acción mutante”: The Provocations of Álex de la Iglesia Peter Buse Núria Triana-Toribio Andrew Willis University of Salford University of Manchester University of Salford Speaking at the Manchester Spanish Film Festival in 2000, Álex de la Iglesia professed that he was not really a film director. “I’m more of a barman”, he claimed, “I just make cocktails”. His films, he implied, were simply an elaborate montage of quotations from other directors, genres, and film-styles, a self-assessment well borne out by Acción mutante (1993), the de la Iglesias team’s1 first feature film, which promiscuously mixes science fiction and comedy, film noir and western, Almodóvar and Ridley Scott. Were such a claim, and its associated renunciation of auteur status, to issue from an American independent director, or even a relatively self-conscious Hollywood director, would it even raise an eyebrow, so eloquently does it express postmodern orthodoxy? And does it make any difference when it comes from a modern Spanish director? As a bravura cut- and-paste job, a frenetic exercise in filmic intertextuality, Acción mutante is highly accomplished, but it would be a mistake to praise or criticize it on the grounds of its postmodern sensibilities alone without taking into account the intervention it made into a specifically Spanish filmic context where, in the words of the title song “Esto no es un juego, es acción mutante”. AFTER THE LEY MIRÓ Álex de la Iglesia has defined his cinema in terms of what it is not. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

El Tratamiento De Las Enfermedades Mentales En El Cine

Universidad Internacional de La Rioja El tratamiento de las enfermedades mentales en el cine Trabajo fin de grado Presentado por: IRENE PINA CHESA Titulación: GRADO EN COMUNICACIÓN Director: JUAN MARTÍN QUEVEDO Zaragoza Junio 2017 1 ÍNDICE Índice de tablas...............................................................................................................................3 Resumen..........................................................................................................................................4 1. Introducción: 1.1. Planteamiento del problema..................................................................................5 1.2. Justificación............................................................................................................5 2. Marco teórico: 2.1. Breve aproximación a la enfermedad mental......................................................7 2.2. Los medios de comunicación y las enfermedades mentales................................8 2.3. Breve recorrido de la enfermedad mental en el cine a lo largo de los años....11 3. Metodología y objetivos: 3.1. Objetivos...............................................................................................................15 3.2. Metodología 3.2.1. Contextualización de las películas seleccionadas..........................16 3.2.2. Selección de la muestra...................................................................20 3.2.3. Análisis de contenidos.....................................................................22 4. Resultados: -

BEHIND the SCENES with FAIRMONT Celebrating a History and Passion for Movie-Making

FAIRMONT LOVES FILM BEHIND THE SCENES WITH FAIRMONT Celebrating a history and passion for movie-making For more than a century, Fairmont Hotels & Resorts has created memorable experiences for all of its guests, including some of the world’s most renowned filmmakers and actors. Fairmont hotels have been the site or setting of countless Hollywood blockbusters and legendary films. When filmmakers and directors want to portray luxury accommodations that truly represent their destinations, they often focus their cameras on Fairmont properties. Many film buffs will know that Home Alone 2 (1992); and North By Northwest (1959) were filmed at The Plaza, A Fairmont Managed Hotel in New York, but guests may not realize such that Fairmont Hotels & Resorts across the globe have also had starring roles in classic films as JFK (1991), Dr. Zhivago (1965), and The Great Gatsby (2013) to name but a few. Fast forward to the 21st century where Fairmont has shone in the spotlight in popular films such as New York Minute (2004) starring Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen; the Angelina Jolie thriller Taking Lives (2004); The Cinderella Man (2005) featuring Russell Crowe and Renee Zellweger; and the blockbuster RED (2010), featuring an all-star cast including Bruce Willis and Morgan Freeman. Fairmont has also appeared in numerous top-rated television productions such as The Bachelorette, Celebrity Mole and TLC’s A Dating Story. Once the productions have wrapped, Fairmont is equally pleased to roll out the red carpet for international stars when they attend prestigious award shows and film festivals from the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) to the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Awards to the International Indian Film Academy (IIFA) Awards – Bollywood’s top night, which has been hosted by both Toronto’s Fairmont Royal York and Fairmont Singapore.