Capacity Building of ASHA in the Monthly Meeting Platforms in PHC and CHC in Uttar Pradesh, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Saharanpur 82

BASE LINE SURVEY IN THE MINORITY CONCENTRATED DISTRICTS OF UTTAR PRADESH (A Report of Saharanpur District) Sponsored by: Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India New Delhi Study conducted by: Dr. R. C. TYAGI GIRI INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES SECTOR-O, ALIGANJ HOUSING SCHEME LUCKNOW-226 024 CONTENTS Title Page No DISTRICT MAP – SAHARANPUR vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii-xii CHAPTER I: OUTLINE OF THE STUDY 1-3 1.1 About the study 1 1.2 Objective of the study 2 1.3 Methodology and Sample design 2 1.4 Tools 3 CHAPTER II: DEVELOPMENT STATUS IN SAHARANPUR DISTRICT 4-19 2.1 Introduction 4 2.2 Demographic Status 5 2.3 Demographic Status by Religion 6 2.4 Structure and Growth in Employment 7 2.5 Unemployment 8 2.6 Land Use Pattern 9 2.7 Coverage of Irrigation and Sources 10 2.8 Productivity of Major Crops 10 2.9 Livestock 11 2.10 Industrial Development 11 2.11 Development of Economic Infrastructure 12 2.12 Rural Infrastructure 13 2.13 Educational Infrastructure 14 2.14 Health Infrastructure 15 2.15 Housing Amenities in Saharanpur District 16 2.16 Sources of Drinking Water 17 2.17 Sources of Cooking Fuel 18 2.18 Income and Poverty Level 19 CHAPTER III: DEVELOPMENT STATUS AT THE VILLAGE LEVEL 20-31 3.1 Population 20 3.2 Occupational Pattern 20 3.3 Land use Pattern 21 3.4 Sources of Irrigation 21 3.5 Roads and Electricity 22 3.6 Drinking Water 22 3.7 Toilet Facility 23 3.8 Educational Facility 23 3.9 Students Enrollments 24 3.10 Physical Structure of Schools 24 3.11 Private Schools and Preferences of the People for Schools 25 3.12 Health Facility -

2012* S. No. Year State Region Reason 1. 2017 Jammu And

INTERNET SHUTDOWNS IN INDIA SINCE 2012* S. Year State Region Reason No. 1. 2017 Jammu Pulwama Mobile Internet services were suspended yet again in Pulwama and district of Kashmir on 16 th August, 2017 to prevent rumour Kashmir mongering after a Lashkar commander was killed in a gunfight with the security forces. 2. 2017 Jammu Kashmir Mobile and broadband Internet services were suspended in the and Valley Kashmir valley in the morning of 15 th August, 2017 as a Kashmir precautionary measure on Independence Day. Services were reportedly restored later in the day. 3. 2017 Jammu Shopian, Internet services were suspended in Shopian and Kulgam district and Kulgam of Kashmir on 13 th August, 2017 to prevent the spreading of Kashmir information after three Hizbul Mujahideen militants including the operations commander, and two army men were killed in an encounter. 4. 2017 Jammu Pulwama Internet services were suspended in Pulwama district of Kashmir and on 9 th August, 2017 as a precautionary measure after three militants Kashmir were killed in a gunfight with the Government forces in the Tral township. However, the services on state-owned Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited remained functional. 5. 2017 Jammu Baramulla Mobile Internet services were suspended in Baramulla district of and Kashmir as a precautionary measure on 5th August, 2017 after Kashmir three LeT militants were killed in an encounter with the security forces in the Sopore town of the district. 6. 2017 Jammu Kashmir Mobile Internet services were suspended yet again across Kashmir and Valley on 1st August, 2017 as a precautionary measure fearing clashes Kashmir after the killing of Lashkar-e-Toiba commander Abu Dujana and his aide in an encounter with the security forces. -

Section-VIII : Laboratory Services

Section‐VIII Laboratory Services 8. Laboratory Services 8.1 Haemoglobin Test ‐ State level As can be seen from the graph, hemoglobin test is being carried out at almost every FRU studied However, 10 percent medical colleges do not provide the basic Hb test. Division wise‐ As the graph shows, 96 percent of the FRUs on an average are offering this service, with as many as 13 divisions having 100 percent FRUs contacted providing basic Hb test. Hemoglobin test is not available at District Women Hospital (Mau), District Women Hospital (Budaun), CHC Partawal (Maharajganj), CHC Kasia (Kushinagar), CHC Ghatampur (Kanpur Nagar) and CHC Dewa (Barabanki). 132 8.2 CBC Test ‐ State level Complete Blood Count (CBC) test is being offered at very few FRUs. While none of the sub‐divisional hospitals are having this facility, only 25 percent of the BMCs, 42 percent of the CHCs and less than half of the DWHs contacted are offering this facility. Division wise‐ As per the graph above, only 46 percent of the 206 FRUs studied across the state are offering CBC (Complete Blood Count) test service. None of the FRUs in Jhansi division is having this service. While 29 percent of the health facilities in Moradabad division are offering this service, most others are only a shade better. Mirzapur (83%) followed by Gorakhpur (73%) are having maximum FRUs with this facility. CBC test is not available at Veerangna Jhalkaribai Mahila Hosp Lucknow (Lucknow), Sub Divisional Hospital Sikandrabad, Bullandshahar, M.K.R. HOSPITAL (Kanpur Nagar), LBS Combined Hosp (Varanasi), -

Research Article

Available Online at http://www.recentscientific.com International Journal of CODEN: IJRSFP (USA) Recent Scientific International Journal of Recent Scientific Research Research Vol. 10, Issue, 11(A), pp. 35764-35767, November, 2019 ISSN: 0976-3031 DOI: 10.24327/IJRSR Research Article SOME MEDICINAL PLANTS TO CURE JAUNDICE AND DIABETES DISEASES AMONG THE RURAL COMMUNITIES OF SHRAVASTI DISTRICT (U.P.) , INDIA Singh, N.K1 and Tripathi, R.B2 1Department of Botany, M.L.K.P.G. College Balrampur (U.P.), India 2Department of Zoology, M.L.K.P.G. College Balrampur (U.P.), India DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24327/ijrsr.2019.1011.4166 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT An ethnobotanical survey was undertaken to collect information from traditional healers on the use Article History: of medicinal plants in rural communities of district Shravasti Uttar Pradesh. The important th Received 4 August, 2019 information on the medicinal plants was obtained from the traditional medicinal people. Present th Received in revised form 25 investigation was carried out for the evaluation on the current status and survey on these medicinal September, 2019 plants. In the study we present 14 species of medicinal plants which are commonly used among the th Accepted 18 October, 2019 rural communities of Shravasti district (U.P.) to cure jaundice and diabetes diseases. This study is th Published online 28 November, 2019 important to preserve the knowledge of medicinal plants used by the rural communities of Shravasti district (U.P.), the survey of the psychopharmacological and literatures of these medicinal plants Key Words: have great pharmacological and ethnomedicinal significance. Medicinal plants, jaundice and diabetes diseases, rural communities of Shravasti. -

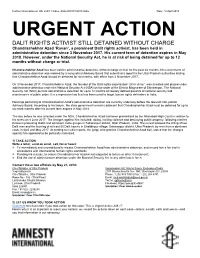

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

Current Condition of the Yamuna River - an Overview of Flow, Pollution Load and Human Use

Current condition of the Yamuna River - an overview of flow, pollution load and human use Deepshikha Sharma and Arun Kansal, TERI University Introduction Yamuna is the sub-basin of the Ganga river system. Out of the total catchment’s area of 861404 sq km of the Ganga basin, the Yamuna River and its catchment together contribute to a total of 345848 sq. km area which 40.14% of total Ganga River Basin (CPCB, 1980-81; CPCB, 1982-83). It is a large basin covering seven Indian states. The river water is used for both abstractive and in stream uses like irrigation, domestic water supply, industrial etc. It has been subjected to over exploitation, both in quantity and quality. Given that a large population is dependent on the river, it is of significance to preserve its water quality. The river is polluted by both point and non-point sources, where National Capital Territory (NCT) – Delhi is the major contributor, followed by Agra and Mathura. Approximately, 85% of the total pollution is from domestic source. The condition deteriorates further due to significant water abstraction which reduces the dilution capacity of the river. The stretch between Wazirabad barrage and Chambal river confluence is critically polluted and 22km of Delhi stretch is the maximum polluted amongst all. In order to restore the quality of river, the Government of India (GoI) initiated the Yamuna Action Plan (YAP) in the1993and later YAPII in the year 2004 (CPCB, 2006-07). Yamuna river basin River Yamuna (Figure 1) is the largest tributary of the River Ganga. The main stream of the river Yamuna originates from the Yamunotri glacier near Bandar Punch (38o 59' N 78o 27' E) in the Mussourie range of the lower Himalayas at an elevation of about 6320 meter above mean sea level in the district Uttarkashi (Uttranchal). -

MAP:Muzaffarnagar(Uttar Pradesh)

77°10'0"E 77°20'0"E 77°30'0"E 77°40'0"E 77°50'0"E 78°0'0"E 78°10'0"E MUZAFFARNAGAR DISTRICT GEOGRAPHICAL AREA (UTTAR PRADESH) 29°50'0"N KEY MAP HARIDWAR 29°50'0"N ± SAHARANPUR HARDWAR BIJNOR KARNAL SAHARANPUR CA-04 TO CA-01 CA-02 W A RDS CA-06 RO O CA-03 T RK O CA-05 W E A R PANIPAT D S N A N A 29°40'0"N Chausana Vishat Aht. U U T T OW P *# P A BAGHPAT Purquazi (NP) E MEERUT R A .! G R 29°40'0"N Jhabarpur D A W N *# R 6 M S MD Garhi Abdullakhan DR 1 Sohjani Umerpur G *# 47 D A E *#W C D Total Population within the Geographical Area as per 2011 A O A O N B 41.44 Lacs.(Approx.) R AL R A KARNAL N W A Hath Chhoya N B Barla T Jalalabad (NP) 63 A D TotalGeographicalArea(Sq.KMs) No.ChargeAreas O AW 1 S *# E O W H *#R A B .! R Kutesra A A 4077 6 Bunta Dhudhli D A Kasoli D RD N R *#M OA S A Pindaura Jahangeerpur*# *# *# K TH Hasanpur Lahari D AR N *# S Khudda O N O *# H Charge Areas Identification Tahsil Names A *# L M 5 Thana Bhawan(Rural) DR 10 9 CA-01 Kairana Un (NP) W *#.! Chhapar Tajelhera CA-02 Shamli .! Thana Bhawan (NP) Beheri *# *# CA-03 Budhana Biralsi *# Majlishpur Nojal Njali *# Basera *# *# *# CA-04 Muzaffarnagar Sikari CA-05 Khatauli Harar Fatehpur Maisani Ismailpur *# *# Roniharji Pur Charthaval (NP) *# CA-06 Jansath *# .! Charthawal Rural Garhi Pukhta (NP) Sonta Rasoolpur Kulheri 3W *# Sisona Datiyana Gadla Luhari Rampur*# *# .! 7 *# *# *# *# *# Bagowali Hind MDR 16 SH 5 Hiranwara Nagala Pithora Nirdhna *# Jhinjhana (NP) Bhainswala *# Silawar *# *# *# Sherpur Bajheri Ratheri LEGEND .! *# *# Kairi *# Malaindi Sikka Chhetela *# *# -

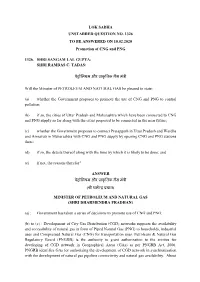

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1326 to BE ANSWERED on 10.02.2020 REGARDING PROMOTION of CNG and PNG List of Geographical Areas Covered Till 10Th CGD Bidding Round

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1326 TO BE ANSWERED ON 10.02.2020 Promotion of CNG and PNG 1326. SHRI SANGAM LAL GUPTA: SHRI RAMDAS C. TADAS: पेट्रोलियम और प्राकृलिक गैस मंत्री Will the Minister of PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government proposes to promote the use of CNG and PNG to control pollution; (b) if so, the cities of Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra which have been connected to CNG and PNG supply so far along with the cities proposed to be connected in the near future; (c) whether the Government proposes to connect Pratapgarh in Uttar Pradesh and Wardha and Amravati in Maharashtra with CNG and PNG supply by opening CNG and PNG stations there; (d) if so, the details thereof along with the time by which it is likely to be done; and (e) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER पेट्रोलियम और प्राकृलिक गैस मंत्री (श्री धमेन्द्र प्रधान) MINISTER OF PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS (SHRI DHARMENDRA PRADHAN) (a) : Government has taken a series of decisions to promote use of CNG and PNG. (b) to (e) : Development of City Gas Distribution (CGD) networks supports the availability and accessibility of natural gas in form of Piped Natural Gas (PNG) to households, industrial uses and Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) for transportation uses. Petroleum & Natural Gas Regulatory Board (PNGRB) is the authority to grant authorization to the entities for developing of CGD network in Geographical Areas (GAs) as per PNGRB Act, 2006. PNGRB identifies GAs for authorizing the development of CGD network in synchronization with the development of natural gas pipeline connectivity and natural gas availability. -

Modeling of Rainfall and Ground Water Fluctuation of Gonda District Uttar Pradesh, India

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2018) 7(5): 2613-2618 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 7 Number 05 (2018) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.705.302 Modeling of Rainfall and Ground Water Fluctuation of Gonda District Uttar Pradesh, India Dinesh Kumar Vishwakarma1*, Rohitashw Kumar2, Kusum Pandey3, Vikash Singh4 and Kuldeep Singh Kushwaha5 1,2College of Agricultural Engineering and Technology, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir, Shalimar Campus Srinagar – Jammu and Kashmir, India 3Department of Soil and Water Conservation Engineering, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, Punjab 141004, India 4Department of Farm Engineering, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005 5Centre of Water Engineering and Management, Central University of Jharkhand – 835205, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Various quantitative analyses are required for complex and dynamic nature of water resources systems to manage it properly. Groundwater table fluctuations over time in shallow aquifer systems need to be evaluated for formulating or designing an K e yw or ds appropriate groundwater development scheme. This paper demonstrates a methodology Precipitation, for modeling rainfall- runoff and groundwater table fluctuations observed in a shallow unconfined aquifer Gonda District Utter Pradesh. The rainfall recharge contributed to its Ground water recharge, Ground annual increment in the ground in water reserve which in turn is reflected in the rise of water table water table during the post monsoon period. The linear regression model between water fluctuation, Karl table and annual rainfall was derived by Karl parson’s method. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Copy of PSC Address.Xlsx

Address of Program Study Centers S.N Districts Name of Institutes Address Contact No 1 Agra District Women Hospital-Agra Shahid Bhagatsingh Rd, Rajamandi Crossing, Bagh Muzaffar 0562 226 7987 Khan, Mantola, Agra, Uttar Pradesh 282002 2Aligarh District Women Hospital-Aligarh Rasal Ganj Rd, City, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh 202001 3 Pt. DDU District Combined Hospital-Aligarh Ramghat Rd, Near Commissioner House, Quarsi, Aligarh, 0571 274 1446 Uttar Pradesh 202001 4 Prayagraj District Women Hospital-Prayagraj 22/26, Kanpur - Allahabad Hwy, Roshan Bagh, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh 211003 5 Azamgarh District Women Hospital-Azamgarh Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg, Balrampur, Harra Ki Chungi, 091208 49999 Sadar, Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh 276001 6 Bahraich District Male Hospital-Bahraich Ghasiyaripura, Friganj, Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh 271801 094150 36818 7 Bareilly District Women Hospital-Bareilly Civil Lines, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh 243003 0581 255 0009 8 Basti District Women Hospital-Basti Ladies hospital, Kateshwar Pur, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 272001 9 Gonda District Women Hospital-Gonda Khaira, Gonda, Uttar Pradesh 271001 11 Etawah District Male Hospital-Etawah Civil Lines, Etawah, Uttar Pradesh 206001 099976 04403 12 Ayodhya District Women Hospital-Ayodhya Fatehganj Rikabganj Road, Rikaabganj, Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh 224001 13 GB Nagar Combined Hospital-GB Nagar C-18, Service Rd, C-Block, Sector 31, Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201301 14 Ghaziabad District Combined Hospital, Sanjay Nagar- District Combined Hospital, Mansi Vihar, Sector 23, Sanjay Ghaziabad Nagar, Ghaziabad, -

Uttar Pradesh District Gazetteers: Muzaffarnagar

GAZETTEER OF INDIA UTTAR PRADESH District Muzaffarnagar UTTAR PRADESH DISTRICT GAZETTEERS MUZAFFARNAGAR ■AHSLl PI AS a* TAR¥K I.AiSv State Editor Published by the Government of Uttar Pradesh (Department of District Gazetteers, U. P„ Lucknow) and Printed by Superintendent Printing & Stationery, U. p, at fbe Government Press, Rampur 1989 Price Rs. 52.00 PREFACE Earlier accounts regarding the Muzaffarnagar district are E. T. Atkinson’s Statistical, Descriptive and Histori¬ cal Account of the North-Western Provinces of India, Vol. II, (1875), various Settlement Reports of the region and H. R. Nevill’s Muzaffarnagar : A Gazetteer (Allahabad, 1903), and its supplements. The present Gazetteer of the district is the twenty- eighth in the series of revised District Gazetteers of the State of Uttar Pradesh which are being published under a scheme jointly sponsored and financed by the Union and the State Governments. A bibliography of the published works used in the preparation of this Gazetteer appears at its end. The census data of 1961 and 1971 have been made the basis for the statistics mentioned in the Gazetteer. I am grateful to the Chairman and members of the State Advisory Board, Dr P. N. Chopra, Ed.',tor, Gazetteers, Central Gazetteers Unit, Ministry of Education and Social Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, and to all those officials and non-officials who have helped in the bringing out of this Gazetteer. D. P. VARUN l.UCKNOW : November 8, 1976 ADVISORY BOARD 1. Sri Swami Prasad Singh, Revenue Minister, Chairman Government of Uttar Pradesh 2. Sri G. C. Chaturvedi, Commissioner-eum- Viet-Chairmsn Secretary, Revenue Department 3.