EBO Background Paper No.3/2016 - the 21St Century Panglong Conference) a Federalism Movement Sprang up in 1961

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Facts About the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - Emref

Important Facts about the 2015 Myanmar General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 2015 October Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF 1 Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF ENLIGHTENED MYANMAR RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT FOUNDATION (EMReF) This report is a product of the Information Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation EMReF is an accredited non-profit research Strategies for Societies in Transition program. (EMReF has been carrying out political-oriented organization dedicated to socioeconomic and This program is supported by United States studies since 2012. In 2013, EMReF published the political studies in order to provide information Agency for International Development Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010- and evidence-based recommendations for (USAID), Microsoft, the Bill & Melinda Gates 2012). Recently, EMReF studied The Record different stakeholders. EMReF has been Foundation, and the Tableau Foundation.The Keeping and Information Sharing System of extending its role in promoting evidence-based program is housed in the University of Pyithu Hluttaw (the People’s Parliament) and policy making, enhancing political awareness Washington's Henry M. Jackson School of shared the report to all stakeholders and the and participation for citizens and CSOs through International Studies and is run in collaboration public. Currently, EMReF has been regularly providing reliable and trustworthy information with the Technology & Social Change Group collecting some important data and information on political parties and elections, parliamentary (TASCHA) in the University of Washington’s on the elections and political parties. performances, and essential development Information School, and two partner policy issues. -

Improvement of Meteorological

IMPROVEMENT OF METEOROLOGICAL OBSERVATION SYSTEM IN MYANMAR By Hla Tun Office No (5), Ministry of Transport and Communications, Department of Meteorology and Hydrology, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar Tel. +95 67 411 250, +95 9 860 1162, Mobile Phone: +95 250 954 642, Fax : (+95) 67 411 526 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Department of Meteorology and Hydrology (DMH) is under the administration of the Ministry of Transport and Communications. Main works performed by DMH are routine observation and analysis of meteorological phenomena, and providing of timely and accurate weather and climate information through acquisition of weather monitoring and dissemination systems for the general public. DMH also provides meteorological and hydrological information for shipping and aviation as well as agricultural and environment activities. Before Cyclonic Storm "Nargis", (103) surface weather observation stations in Myanmar used manual observing system. As at then, we are improved on installation of Automated Weather Observing Systems at 14 stations including at former Headquarter of National Meteorological Center (NMCs) namely Yangon (Kaba-aye) and new Headquarter of National Meteorological Center (NMCs) namely Nay Pyi Taw. Early months of this year (2016), regarding the Grant Aid Project of Japan, we installed additional Surface Automated Weather Observing Systems (AWS) at existing 30 Meteorological observation stations such as Nay Pyi Taw (Early Warning Center), Yangon (Kaba-aye), Mandalay, Putao, Myitkyina, Bhamo, Lashio, Taunggyi, Kengtung, Namsam, Hakha, Hkamti, Kalay, Monywa, Meikhtila, Magway, Sittwe, Kyauk-phyu, Thandwe, Gwa, Taungu, Bago, Hmawbi, Pathein, Laputta, Loikaw, Hpa-an, Mawlamyine, Dawei and Kawthong. Furthermore, one of the three (3) new Doppler Weather Radars, it is already installed in 2015 and remaining two radars we expected to be completed middle of this year and the project will be complete by next year of 2017. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Myanmar Public Disclosure Authorized

SFG1932 REV Republic of the Union of Myanmar Public Disclosure Authorized Myanmar Flood and Landslides Emergency Recovery Project Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized May 23rd, 2016 [Revised Draft] Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Table of Contents Abbreviations _____________________________________________________________________ 3 I. Background ______________________________________________________________ 4 II. Project Development Objective ______________________________________________ 7 III. Project Description ________________________________________________________ 7 IV. Project Locations and Some Salient Social and Environmental Characteristics ______ 9 V. Possible Social and Environmental Impacts/Risks ______________________________ 11 VI. Legal Framework ______________________________________________________ 13 VII. National Legal Framework ______________________________________________ 13 VIII. Categorization and World Bank Safeguard Policies Triggered __________________ 17 IX. Project approach to Addressing Environmental and Social Safeguard issues _______ 21 X. Institutional Arrangements ________________________________________________ 25 XI. Project Monitoring and Grievance Mechanism (GRM) _________________________ 30 XII. Capacity Development Plan ______________________________________________ 32 XIII. Estimated Cost ________________________________________________________ 33 XIV. Consultation and Disclosure _____________________________________________ -

Mawlaik and Returning Downstream Towards Monywa

Pandaw River Expeditions EXPEDITION No 4 THE CHINDWIN: 7 NIGHTS 7 NIGHTS The loveliest of rivers. In the past we only offered this during the monsoon due to water levels, but now our ultra low draught Pandaws can sail through to February. The river carves it way through mountains and forests and we stop at delightful unspoilt little towns. Our objective, Homalin is the capital of Nagaland and close to the India border. We will ply the Upper Chindwin weekly between Monywa and Homalin. Monywa is under three hours from Mandalay and the car transfer is included with the cruise. Homalin is now connected by scheduled flight with Mandalay. Two fabulous itineraries: The Monywa to Homalin (and vv) itinerary sails from July to August and October to November. We have a revised itinerary from Monywa to Kalewa (and vv) operating December to February. Please note river banks can be steep and walks through villages are on the daily program. Medium fitness is requiered. Late bookings: please note that Chindwin expeditions need special permits, which can take up to 3 weeks. We kindly ask you to contact us via email or phone for short notice bookings. Cruise Price Includes: One way domestic flight, entrance fees, guide services (English language), gratuities to crew, main meals, local mineral water, jugged coffee, teas & tisanes. Cruise Price Excludes: International flights, port dues (if levied), laundry, all visa costs, fuel surcharges (see terms and conditions), all beverages except local mineral water, jugged coffee, teas & tisanes and tips to tour guides, local guides, bus drivers, boat operators and cyclo drivers. -

Early Childhood Care and Development- END of PROGRAMME EVALUATION !

early childhood care and Development- END OF PROGRAMME EVALUATION ! Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations!..................................................................................................................................................!5! Tables and figures!.....................................................................................................................................................................!6! 1.! EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS!.........................!7! 2. INTRODUCTION – ORGANIZATIONAL AND PROGRAMMATIC RELEVANCE!............!14! 3. METHODOLOGY!......................................................................................................................................!15! 3.1 ! INTRODUCTION!.....................................................................................................................................................!15! 3.2 ! DATA TOOLS AND DESIGN PROCESS!...............................................................................................................!16! 3.3 ! SAMPLE AND SAMPLE SELECTION!....................................................................................................................!17! 3.4 ! FIELD RESEARCH AND DATA COLLECTION!...................................................................................................!18! 3.5 ! LIMITATIONS!..........................................................................................................................................................!18! -

China Thailand Laos

MYANMAR IDP Sites in Shan State As of 30 June 2021 BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH MYANMAR Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND CHINA List of IDP Sites In nothern Shan No. State Township IDP Site IDPs 1 Hseni Nam Sa Larp 267 2 Hsipaw Man Kaung/Naung Ti Kyar Village 120 3 Bang Yang Hka (Mung Ji Pa) 162 4 Galeng (Palaung) & Kone Khem 525 5 Galeng Zup Awng ward 5 RC 134 6 Hu Hku & Ho Hko 131 SAGAING Man Yin 7 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church) 245 Man Pying Loi Jon 8 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church-2) 155 Man Nar Pu Wan Chin Mu Lin Huong Aik 9 Mai Yu Lay New (Ta'ang) 398 Yi Hku La Shat Lum In 22 Nam Har 10 Kutkai Man Loi 84 Ngar Oe Shwe Kyaung Kone 11 Mine Yu Lay village ( Old) 264 Muse Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan 12 Mung Hawm 170 Nawng Mo Nam Kat Ho Pawt Man Hin 13 Nam Hpak Ka Mare 250 35 ☇ Konkyan 14 Nam Hpak Ka Ta'ang ( Aung Tha Pyay) 164 Chaung Wa 33 Wein Hpai Man Jat Shwe Ku Keng Kun Taw Pang Gum Nam Ngu Muse Man Mei ☇ Man Ton 15 New Pang Ku 688 Long Gam 36 Man Sum 16 Northern Pan Law 224 Thar Pyauk ☇ 34 Namhkan Lu Swe ☇ 26 Kyu Pat 12 KonkyanTar Shan Loi Mun 17 Shan Zup Aung Camp 1,084 25 Man Set Au Myar Ton Bar 18 His Aw (Chyu Fan) 830 Yae Le Man Pwe Len Lai Shauk Lu Chan Laukkaing 27 Hsi Hsar 19 Shwe Sin (Ward 3) 170 24 Tee Ma Hsin Keng Pang Mawng Hsa Ka 20 Mandung - Jinghpaw 147 Pwe Za Meik Nar Hpai Nyo Chan Yin Kyint Htin (Yan Kyin Htin) Manton Man Pu 19 Khaw Taw 21 Mandung - RC 157 Aw Kar Shwe Htu 13 Nar Lel 18 22 Muse Hpai Kawng 803 Ho Maw 14 Pang Sa Lorp Man Tet Baing Bin Nam Hum Namhkan Ho Et Man KyuLaukkaing 23 Mong Wee Shan 307 Tun Yone Kyar Ti Len Man Sat Man Nar Tun Kaw 6 Man Aw Mone Hka 10 KutkaiNam Hu 24 Nam Hkam - Nay Win Ni (Palawng) 402 Mabein Ton Kwar 23 War Sa Keng Hon Gyet Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Nawng Ae 25 Namhkan Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) 338 Si Ping Kaw Yi Man LongLaukkaing Man Kaw Ho Pang Hopong 9 16 Nar Ngu Pang Paw Long Htan (Tart Lon Htan) 26 Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) II 32 Ma Waw 11 Hko Tar Say Kaw Wein Mun 27 Nam Hkam Catholic Church ( St. -

Country Report Myanmar

Country Report Myanmar Natural Disaster Risk Assessment and Area Business Continuity Plan Formulation for Industrial Agglomerated Areas in the ASEAN Region March 2015 AHA CENTRE Japan International Cooperation Agency OYO International Corporation Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Overview of the Country Basic Information of Myanmar 1), 2), 3) National Flag Country Name Long form: Republic of the Union of Myanmar Short form: Myanmar Capital Naypidaw Area (km2) Total : 676,590 Land: 653,290 Inland Water: 23,300 Population 53,259,018 Population density 82 (people/km2 of land area) Population growth 0.9 (annual %) Urban population 33 (% of total) Languages Myanmar Ethnic Groups Burmese (about 70%),many other ethnic groups Religions Buddhism (90%), Christianity, Islam, others GDP (current US$) (billion) 55(Estimate) GNI per capita, PPP - (current international $) GDP growth (annual %) 6.4(Estimate) Agriculture, value added 48 (% of GDP) Industry, value added 16 (% of GDP) Services, etc., value added 35 (% of GDP) Brief Description Myanmar covers the western part of Indochina Peninsula, and the land area is about 1.8 times the size of Japan. Myanmar has a long territory stretching north to south, with the Irrawaddy River running through the heart of the country. While Burmese is the largest ethnic group in the country, the country has many ethnic minorities. Myanmar joined ASEAN on July 23, 1997, together with Laos. Due to the isolationist policy adopted by the military government led by Ne Win which continued until 1988, the economic development of Myanmar fell far behind other ASEAN countries. Today, Myanmar is a republic, and President Thein Sein is the head of state. -

SAGAING REGION, KALAY DISTRICT Kalay Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census SAGAING REGION, KALAY DISTRICT Kalay Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Sagaing Region, Kalay District Kalay Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Sagaing Region, showing the townships Kalay Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 348,573 2 Population males 167,558 (48.1%) Population females 181,015 (51.9%) Percentage of urban population 37.4% Area (Km2) 2,337.8 3 Population density (per Km2) 149.1 persons Median age 25.6 years Number of wards 19 Number of village tracts 41 Number of private households 72,769 Percentage of female headed households 25.2% Mean household size 4.7 persons4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 30.8% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 64.4% Elderly population (65+ years) 4.8% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 55.4 Child dependency ratio 47.9 Old dependency ratio 7.5 Ageing index 15.7 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 93 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 95.2% Male 97.2% Female 93.4% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 11,118 3.2 Walking 4,032 1.2 Seeing 4,437 1.3 Hearing 4,016 1.2 Remembering 4,229 1.2 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 196,618 70.4 Associate -

TRENDS in SAGAING Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN SAGAING Photo Credits William Pryor Mithulina Chatterjee Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN SAGAING UNDP MYANMAR The State of Local Governance: Trends in Sagaing - UNDP Myanmar 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive summary 1 - 3 1. Introduction 4 - 5 2. Methodology 6 - 8 3. Sagaing Region overview and regional governance institutions 9 - 24 3.1 Geography 11 3.2 Socio-economic background 11 3.3 Demographic information 12 3.4 Sagaing Region historical context 14 3.5 Representation of Sagaing Region in the Union Hluttaws 17 3.6 Sagaing Region Legislative and Executive Structures 19 3.7 Naga Self-Administered Zone 21 4. Overview of the participating townships 25 - 30 4.1 Introduction to the townships 26 4.1.1 Kanbalu Township 27 4.1.2 Kalewa Township 28 4.1.3 Monywa Township 29 4.1.4 Lahe Township (in the Naga SAZ) 30 5. Governance at the frontline – participation in planning, responsiveness for local service provision, and accountability in Sagaing Region 31- 81 5.1 Development planning and participation 32 5.1.1 Planning Mechanisms 32 5.1.2 Citizens' perspectives on development priorities 45 5.1.3 Priorities identified at the township level 49 5.2 Basic services - access and delivery 50 5.2.1 General Comments on Service Delivery 50 5.2.2 Health Sector Services 50 5.2.3 Education Sector Services 60 5.2.4 Drinking Water Supply Services 68 5.3 Transparency and accountability 72 5.3.1 Citizens' knowledge of governance structures 72 5.3.2 Citizen access to information relevant to accountability 76 5.3.3 Safe, productive venues for voicing opinions 79 6. -

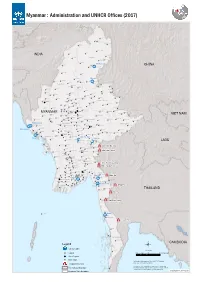

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe -

Disappeared Lists

Date of Section of No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Disapperance Law The military arrested him at his house for the solo protest on 27-Mar- 2021. And he was sent to Taikkyi police station then Insein prison. He was sentenced for 7 days and (Ko) Kyaw Kyaw Taikkyi Township, released on 02-Apr-2021. He went 1 M/49 Civilian 2-Apr-21 Disappeared Lwin Yangon missing since his release and his family was searching for him at the prison but the military told them that he had been released and asked them to search for him in other police stations. The junta troop entered Thabyay Aye village to arrest U Thaw Pa and started shooting around 3 am on 02- Chin Pone Village, Apr-2021. Many local defense force 2 (U) Aung Nyein M/50 Civilian 2-Apr-21 Disappeared Yinmabin Township, were injuried and the fight between Sagaing Region the terrorist group and local defense force continued to happen for hours. He went missing during the conflict. The junta troop entered Thabyay Aye village to arrest U Thaw Pa and started shooting around 3 am on 02- Nga Pyat Village, Kani Apr-2021. Many local defense force 3 (U) Soe Thu M/32 Civilian 2-Apr-21 Disappeared Township, Sagaing were injuried and the fight between Region the terrorist group and local defense force continued to happen for hours. He went missing during the conflict. He went missing during the conflict between the local defense force and Mogaung Village, Kani (Ko) Nay Lin Aung the junta regime around Thabyay 4 M/18 Civilian 15-Apr-21 Disappeared Township, Sagaing (aka) Htet Shar Aye village on the Monywa-Kalay Region highway on 15-Apr-2021.