Scã¨Nes À Faire As Identity Trait Stereotyping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protestors Stress Protocol

Protestors stress protocol by Jeff Moore a petition "supported For the second time this several times to discuss the by...New World Coalition, semester, this protocol has protocol, there was a delay The Colby administration SOBHU, Off-campus not been followed by the in putting up notices," is "cooperating very well" in Organization, Women's administration," the Griffen said "There was a > i meeting the demands of last Group (and) IFC," was the protestors charged. lack of seriousness (on the o Friday's demonstrators. administration's failure to A September 15, 1982 copy part.of the administration) According to Sarah follow a protocol for of the "Protocol for Women in dealing with the problem. !. Griff en, an organizer of "the incidents of sexual Counselors in the Event of They may have had the :. group of concerned harassment and rape. Assault-Rape" and a intent but they were not students'' who led the protest "One part of the protocol," September 16, 1982 copy of following through with on in front of Miller Library, according to a letter the "Sexual Assault-Rape action." rlaDean of Students Janice circulated by last week's Protocol" to be followed by "Four weeks ago I went in .7 Seitzinger has met with them demonstration leaders, security officers both to speak to Janice . ( three times this week "to "calls for the posting of the stipulate that "safety (Seitzinger) after I heard decide on a series of things." incident immediately after it advisories" be posted about the Peeping Tom if; One of the primary is reported to alert the Colby throughout campus. -

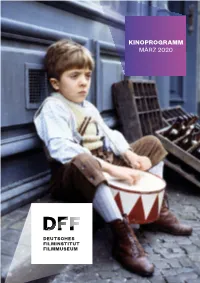

Kinoprogramm März 2020

KINOPROGRAMM MÄRZ 2020 DEUTSCHES FILMINSTITUT FILMMUSEUM DEUTSCHES FILMINSTITUT FILMMUSEUM ** ALLES IST FILM EVERYTHING IS FILM FILME IN ORIGINALFASSUNG DIE BLECHTROMMEL VOLKER SCHLÖNDORFF S.9 ORIGINAL LANGUAGE PROGRAM March highlights Aus dem DFF 2 Ausstellung: Maximilian Schell 4 Das Kino des DFF zeigt Filme grundsätzlich in Originalfassung und nach Verfügbarkeit deutsch Filmprogramm oder englisch untertitelt. The DFF cinema shows films in their original Close-up: Mario Adorf 6 language version and subtitled in German if The Act of Filming – Reflexionen über 10 available (look for the abbreviations OF or Kino und Politik OmU). For our international guests we mark ver- 250 Jahre Friedrich Hölderlin 16 sions subtitled in English with the abbreviation Werkschau Marina de Van 18 OmeU. Klassiker & Raritäten: Maximilian Schell 20 Late Night Kultkino 22 • German actor Mario Adorf in „Close-up“: selec- ted films in Italian with English subtitles p. 7 TAXICHAUFFEUR BÄNZ WERNER DÜGGELIN S. 20 LONE WOLF MCQUADE STEVE CARVER S. 22 • Series „The Act of Filming“ on political cinema with English subtitles & guest Tamer El Said p. 10 • Discover French director Marina de Van’s most important works with English subtitles p. 18 • Maximilian Schell in his key roles, including screenings in English p. 20 Further highlights include: • Late Night Cult Films in English p. 22 • Ang Lee‘s early work XI YAN in Mandarin and English p. 23 • CHARLES MORT OU VIF in French p. 26 • Silent films from Uzbekistan: landmarks of Central Asian cinema p. 27 Language versions can be found in the film descriptions and in the monthly calendar in the middle of this brochure, with expla- nations for abbreviations in English. -

Sundayiournal

STANDING STRONG FOR 1,459 DAYS — THE FIGHT'S NOT OVER YET JULY 11-17, 1999 THE DETROIT VOL. 4 NO. 34 75 CENTS S u n d a yIo u r n a l PUBLISHED BY LOCKED-OUT DETROIT NEWSPAPER WORKERS ©TDSJ JIM WEST/Special to the Journal Nicholle Murphy’s support for her grandmother, Teamster Meka Murphy, has been unflagging. Marching fourward Come Tuesday, it will be four yearsstrong and determined. In this editionOwens’ editorial points out the facthave shown up. We hope that we will since the day in July of 1995 that ofour the Sunday Journal, co-editor Susanthat the workers are in this strugglehave contracts before we have to put Detroit newspaper unions were forcedWatson muses on the times of happiuntil the end and we are not goingtogether any another anniversary edition. to go on strike. Although the companess and joy, in her Strike Diarywhere. on On Pages 19-22 we show offBut four years or 40, with your help, nies tried mightily, they never Pagedid 3. Starting on Page 4, we putmembers the in our annual Family Albumsolidarity and support, we will be here, break us. Four years after pickingevents up of the struggle on the record.and also give you a glimpse of somestanding of strong. our first picket signs, we remainOn Page 10, locked-out worker Keiththe far-flung places where lawn signs— Sunday Journal staff PAGE 10 JULY 11 1999 Co-editors:Susan Watson, Jim McFarlin --------------------- Managing Editor: Emily Everett General Manager: Tom Schram Published by Detroit Sunday Journal Inc. -

Copyright Infringement

COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT Mark Miller Jackson Walker L.L.P. 112 E. Pecan, Suite 2400 San Antonio, Texas 78205 (210) 978-7700 [email protected] This paper was first published in the State Bar of Texas Corporate Counsel Section Corporate Counsel Review, Vol. 30, No. 1 (2011) The author appreciates the State Bar’s permission to update and re-publish it. THE AUTHOR Mark Miller is a shareholder with Jackson Walker L.L.P., a Texas law firm with offices in San Antonio, Dallas, Houston, Austin, Ft. Worth, and San Angelo. He is Chair of the firm’s intellectual property section and concentrates on transactions and litigation concerning intellectual property, franchising, and antitrust. Mr. Miller received his B.A. in Chemistry from Austin College in 1974 and his J.D. from St. Mary’s University in 1978. He was an Associate Editor for St. Mary’s Law Journal; admitted to practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office in 1978; served on the Admissions Committee for the U.S. District Court, Western District of Texas, and been selected as one of the best intellectual property lawyers in San Antonio. He is admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth and Tenth Circuits, the District Courts for the Western, Southern, and Northern Districts of Texas, and the Texas Supreme Court. He is a member of the American Bar Association’s Forum Committee on Franchising, and the ABA Antitrust Section’s Committee on Franchising. Mr. Miller is a frequent speaker and writer, including “Neglected Copyright Litigation Issues,” State Bar of Texas, Intellectual Property Section, Annual Meeting, 2009, “Unintentional Franchising,” 36 St. -

1983 Houston Gay Pride

MARK SPAETH City Council Place 4 "Our city is beautiful and unique-known for its harmony of diverse lifestyles" ~ LET'S ELECT A COUNCIL MEMBER WHO IS SENSITIVE TO ALL THE INTERESTS OF THE COMMUNITY. AUSTIN! DON'T LETTHIS OPPORTUNITY PASS Pol. adv. pd. for by Mark Spaeth Campaign for City Council, 904 West Avenue, Austin, TX. 78701,474-4848 IT'S OUR BIRTHDAY ... AND YOU GET THE PRESENT!!! In celebration of our 4th anniversary in HOUSTON and our 3rd in DALLAS JOIN NOW AND GET $100 OFF!!! At the PITNESS EXCHANGE we've just DOUBLED OUR PREE WEIGHTS and added two abdominal machines to our DOUBLE LINES OP NAUTILUS EQUIPMENT. Available also are Suntana, jacuzzi, sauna, juices, great music and more. WE'RE NOT GETTING OLDER, WE'RE GETTING BETTER! I FIRST MEN'S NIGHT OUT featuring· .. PflUl PflRI<ER and dancers assembled from across the statel Special Midnight Drawing for prizes worth over $2,200~ Music Environment controlled by Bob Deane New Visuals by James Wyatt Tickets $ 7 in advance OFFER EXPIRES APRIL 30TH .... ENVIRONMENTAL OFF THE STREET LOBO BOOKS HOP 3921 Cedar Springs 4008·C Cedar Springs HOURS: MON-FRI 6AM-10PM SAT IOAM-8PM SUN NOON-6PM SENSORY OAK LAWN RECORDS 3810 Congress, 121 Memberships reciprocal between Dallas and Houston. PRODUCTIONS INC. 3409 Oak lawn Avenue.Suites 2121214. DALLAS HOUSTON Dallas. Texas 75219 Phone 214/521-8766 2615 Oaklawn rf§JfIT~ 3307 Richmond at Maple at Buffalo Spdwy. PAGE 4 526-1220 ~XCIH~ 524-9932 TWT APRIL 22 - 28. 1983 NAUTILUS FOR MEN \\DN _---CONTENTS Volume 9, Number5 April 22-28, 1983 11TWTNEWS . -

The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights – Meeting with President 05/13/1983 – Father Virgil Blum (2 of 4) Box: 34

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Blackwell, Morton: Files Folder Title: The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights – Meeting with President 05/13/1983 – Father Virgil Blum (2 of 4) Box: 34 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON 4/28/83 MEMORANDUM - TO: FAITH WHITTLESEY (COORDINATE WITH RICHARD WILLIAMSON) FROM: FREDERICK J. -RYAN, JR. ~ SUBJ: APPROVED PRESIDENTIAL ACTIVITY MEETING: Brief greeting and photo with Father Virgil Blum - on th~ occasion of the 10th anniversary of the Catholic League ' for Religious and Civil Rights DATE: May 13, 1983 TIME: 2:00 pm DURATION: · 10 minutes LOCA'i'ION: Oval. Office RE~.ARKS REQUIRED: Background to be covered in briefing paper MEDIA COVERAGE: If any, coordinate with Press Office FIRST LADY PARTICIPATION: No NOTE: PROJECT OFFICER, SEE ATTACHED CHECKLIST cc: A. Bakshian M. McManus R. Williamson R. Darrnan J. Rosebush R. DeProspero B. Shaddix K. Duberstein W. Sittrnann D. Fischer L. Speakes C. Fuller WHCA Audio/Visual W. Henkel WHCA Operations E. Hickey A. lvroble ski G. Hodges Nell Yates THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON April 21, 1983 MEMORANDUM TO MICHAEL K. DEAVER FAITH R. WHITTLESEY FROM: RICHARDS. WILLIAMSON RE: CATHOLIC LEAGUE FOR RELIGIOUS AND CIVIL RIGHTS I am prompted to forward this both to you as a result of our r -.I recent luncheon meeting on blue collar workers coupled with materials I have received from Bill Gavin. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

The Official Chuck Norris Fact Book

THE OFFICIAL CHUCK NORRIS FACT BOOK 1 CNorris.indd i 9/1/2009 10:17:59 AM “Chuck Norris is a close friend who I love like a brother (and who once put a choke hold on me at my request, which I immediately regretted). I was delighted to find that The Official Chuck Norris Fact Book includes many of the great stories Chuck has told me that I wished others could hear. This book is fun, encouraging, and inspirational. I thoroughly enjoyed it. So will you!” RANDY ALCORN author of Heaven and If God Is Good 2 CNorris.indd ii 9/1/2009 2:59:38 PM THE OFFICIAL CHUCK NORRIS FACT BOOK 101 OF CHUCK’S FAVORITE FACTS AND STORIES CHUCK NORRIS with Todd DuBord Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. CAROL STREAM, ILLINOIS 3 CNorris.indd iii 9/1/2009 10:18:15 AM Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com. Visit Chuck Norris’s Web site at www.chucknorris.com. TYNDALE and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. The Official Chuck Norris Fact Book: 101 of Chuck’s Favorite Facts and Stories Copyright © 2009 by Carlos Ray Norris. All rights reserved. Cover photo taken by Mark Hanauer Photography, copyright © by Chuck Norris. All rights reserved. Interior T-shirt designs copyright © by Thundercreek Designs. All rights reserved. Interior caricature illustrations by Antonis Papantoniou, copyright © by Chuck Norris. All rights reserved. Designed by Ron Kaufmann Published in association with the literary agency of Mark Sweeney & Associates, 28540 Altessa Way, Suite 201, Bonita Springs, FL 34135. -

Nysba Fall 2020 | Vol

NYSBA FALL 2020 | VOL. 31 | NO. 4 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association In This Issue n Tackling Coronavirus: Maintaining Privacy in the National Football League Amid a Global Pandemic n Photojournalism and Drones in New York City: Recent Legal Issues n Exit for a Better Start: How to Break a Commercial Lease n From “Location, Location . .” to “On Location”: Considerations in Using Your Client’s Home as a Film Location ....and more NYSBA.ORG/EASL Entertainment, Arts & Sports Law Section Thank you to our Music Business and Law Conference 2020 Sponsors, Eminutes and Zanoise! Table of Contents Page Remarks From the Chair ............................................................................................................................................ 4 By Barry Werbin Editor’s Note/Pro Bono Update ............................................................................................................................... 5 By Elissa D. Hecker Law Student Initiative Writing Contest .............................................................................................................................. 7 The Phil Cowan–Judith Bresler Memorial Scholarship Writing Competition ........................................................... 8 NYSBA Guidelines for Obtaining MCLE Credit for Writing ....................................................................................... 10 Sports and Entertainment Immigration: A Smorgasbord -

Kyle Barrowman

JOMEC Journal Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies No Way as Way: Towards a Poetics of Martial Arts Cinema Kyle Barrowman The University of Chicago Email: [email protected] Keywords Martial Arts Film Studies Cultural Studies Theory Post-Theory Poetics Abstract This essay explores the history and evolution of academic film studies, focusing in particular on the development of an admirably interdisciplinary branch of inquiry dedicated to exploring martial arts cinema. Beginning with the clash between the auteur theory and the development of a psycholinguistic model of film theory upon film studies’ academic entrenchment and political engagement in the 1960s and 1970s, this essay continues past the Historical Turn in the 1970s and 1980s into the Post-Theory era in the 1990s and beyond, by which time studies of martial arts cinema, thanks in large part to the ‘cultural studies intervention’, began to attract scholars from various academic disciplines, most notably cultural studies. At once diagnostic and prescriptive, this essay seeks to historically contextualize the different modes of thinking that have informed past engagements with the cinema in general while also offering a polemical meta- criticism of exemplars in an effort to highlight deficiencies in the current interpretive orthodoxy informing contemporary engagements with martial arts cinema in particular. This essay endeavors to find a way to allow the larger enterprise of ‘Martial Arts Studies’ to compliment, rather than colonize and cannibalize, the study of martial arts cinema, and this polemic offers as a model for scholars both in and out of film studies a ‘poetics of martial arts cinema’ committed to dialectical, ‘alterdisciplinary’ scholarship. -

TOOELE Delegation Vows Fight in N-Waste Standoff

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE RANSCRIPT Lady Buffs T battle back for another hard-fought victory See A10 BULLETIN March 22, 2005 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 111 NO. 86 50 cents Sweet Serenade Delegation vows fight in N-waste standoff by Karen Lee Scott STAFF WRITER The battle over an above-ground nuclear waste repository at the Skull Valley Goshute Indian Reservation isn’t over yet, but opposing sides are making sure their opinions are heard loud and clear before the full Nuclear Regulatory Commission votes on the matter. The Atomic Safety and Licensing Board (a three- member panel of the NRC) has already given it’s nod of approval (2-1) for Private Fuel Storage to tempo- rarily house 4,000 casks of spent nuclear fuel rods on the reservation but that doesn’t mean the entire NRC will concur with the recommendation. In an effort to sway the vote against allowing the project, Utah’s two senators (Orrin Hatch and Bob Bennett) and three Congressmen (Jim Matheson, Chris Cannon and Rob Bishop) sent a letter to NRC Chairman Nils Diaz last week stating their opposition to the site. “Due to the possibility of an accidental or deliber- ate aircraft crash, concerns over the safety of the photography / Troy Boman waste during transportation and storage, and uncer- Members of the Baird clan (l-r) Jennifer, Jana and Julee, asked longtime Grantsville resident Farrell Butler onto the stage and surprised him with a song and tainty regarding liability, the Utah Congressional del- dance during the opening of the Old Folks Sociable program Saturday afternoon. -

Four Star Films, Box Office Hits, Indies and Imports, Movies A

Four Star Films, Box Office Hits, Indies and Imports, Movies A - Z FOUR STAR FILMS Top rated movies and made-for-TV films airing the week of the week of Feb 7 - 13, 2021 Apocalypse Now (1979) Cinemax Sun. 12:59 p.m. Beauty and the Beast (1991) Freeform Sat. 7:40 p.m. Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (2007) Cinemax Sun. 4:46 a.m. Brief Encounter (1945) TCM Sat. 1:30 a.m. Casablanca (1942) TCM Fri. 5 p.m. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007) Cinemax Fri. 4:22 a.m. The Enchanted Cottage (1945) TCM Sun. 3 a.m. Forrest Gump (1994) AMC Mon. 7 p.m. AMC Tues. 5 p.m. Gigi (1958) TCM Sat. 9:15 a.m. Glory (1989) Starz Mon. 9:19 p.m. The Heiress (1949) TCM Sun. 12:30 p.m. L.A. Confidential (1997) Encore Sun. 10:24 p.m. Encore Mon. 2:25 p.m. Encore Wed. 11:26 a.m. Encore Wed. 9 p.m. Marty (1955) TCM Fri. 9:45 p.m. The Philadelphia Story (1940) TCM Sat. 11:15 p.m. Platoon (1986) Sundance Tues. 8 p.m. Sundance Wed. 9:30 a.m. Rain Man (1988) Ovation Sun. 10:30 a.m. Ovation Wed. Noon Ovation Sat. 8 p.m. Rear Window (1954) TCM Fri. 3:15 a.m. The Shawshank Redemption (1994) Paramount Fri. 7 p.m. The Silence of the Lambs (1991) Showtime Sat. 10:30 p.m. Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) Sundance Mon. 10:30 p.m.