Slavery, Memory and Orality: Analysis of Song Texts from Northern Ghana Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper East Region

REGIONAL ANALYTICAL REPORT UPPER EAST REGION Ghana Statistical Service June, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ghana Statistical Service Prepared by: ZMK Batse Festus Manu John K. Anarfi Edited by: Samuel K. Gaisie Chief Editor: Tom K.B. Kumekpor ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There cannot be any meaningful developmental activity without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, and socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. The Kilimanjaro Programme of Action on Population adopted by African countries in 1984 stressed the need for population to be considered as a key factor in the formulation of development strategies and plans. A population census is the most important source of data on the population in a country. It provides information on the size, composition, growth and distribution of the population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of resources, government services and the allocation of government funds among various regions and districts for education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users with an analytical report on the 2010 PHC at the regional level to facilitate planning and decision-making. This follows the publication of the National Analytical Report in May, 2013 which contained information on the 2010 PHC at the national level with regional comparisons. Conclusions and recommendations from these reports are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based policy formulation, planning, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programs. -

Volta-Hycos Project

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANISATION Weather • Climate • Water VOLTA-HYCOS PROJECT SUB-COMPONENT OF THE AOC-HYCOS PROJECT PROJECT DOCUMENT SEPTEMBER 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………….v 1 WORLD HYDROLOGICAL CYCLE OBSERVING SYSTEM (WHYCOS)……………1 2. BACKGROUNG TO DEVELOPMENT OF VOLTA-HYCOS…………………………... 3 2.1 AOC-HYCOS PILOT PROJECT............................................................................................... 3 2.2 OBJECTIVES OF AOC HYCOS PROJECT ................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 General objective........................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.2 Immediate objectives .................................................................................................................. 3 2.3 LESSONS LEARNT IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AOC-HYCOS BASED ON LARGE BASINS......... 4 3. THE VOLTA BASIN FRAMEWORK……………………………………………………... 7 3.1 GEOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS....................................................................................................... 7 3.2 COUNTRIES OF THE VOLTA BASIN ......................................................................................... 8 3.3 RAINFALL............................................................................................................................. 10 3.4 POPULATION DISTRIBUTION IN THE VOLTA BASIN.............................................................. 11 3.5 SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS........................................................................................... -

The Composite Budget of the East Gonja District Assembly for the 2015

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE COMPOSITE BUDGET OF THE EAST GONJA DISTRICT ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2015 FISCAL YEAR 1 For Copies of this MMDA’s Composite Budget, please contact the address below: The Coordinating Director, East Gonja District Assembly Northern Region This 2015 Composite Budget is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh or www.ghanadistricts.com 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: ASSEMBLY’S COMPOSITE BUDGET STATEMENT BACKGROUND Establishment of the District Assembly.............................................................................................................7 The Structure of theAssembly..........................................................................................................................7 Vision of the District........................................................................................................................................7 Mission Statement............................................................................................................................................8 The Values ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Objectives ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Location...........................................................................................................................................................9 Climate.............................................................................................................................................................9 Vegetation .....................................................................................................................................................10 -

Report British Togoland

c. 452 (b). M. 166 (b). 1925. VI. Geneva, September 3rd, 1925. REPORTS OF MANDATORY POWERS Submitted to the Council of the League of Nations in Accordance with Article 2 2 of the Covenant and considered by the Permanent Mandates Commission at its Sixth Session (June-July 1 9 2 5 J. VI REPORT BY HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT ON THE ADMINISTRATION UNDER MANDATE OF BRITISH TOGOLAND FOR THE YEAR 1924 SOCIÉTÉ DES NATIONS — LEAGUE OF NATIONS GENÈVE — 1925 ---- GENEVA NOTES BY THE SECRETARIAT OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS This edition of the reports submitted to the Council of the League of Nations by the Mandatory Powers under Article 22 of the Covenant is published in exe cution of the following resolution adopted by the Assembly on September 22nd, 1924, at its Fifth Session : “ The Assembly . requests that the reports of the Mandat ory Powders should be distributed to the States Members of the League of Nations and placed at the disposal of the public wrho may desire to purchase them. ” The reports have generally been reproduced as received by the Secretariat. In certain cases, however, it has been decided to omit in this new edition certain legislative and other texts appearing as annexes, and maps and photographs contained in the original edition published by the Mandatory Power. Such omissions are indicated by notes by the Secretariat. The annual report on the administration of Togoland under British mandate for the year 1924 was received by the Secretariat on June 15th, 1925, and examined by the Permanent Mandates Commission on July 6th, 1925, in the presence of the accredited representative of the British Government, Captain E. -

Presentation on the Navrongo Health Research Centre

Navrongo Health Research Centre Ghana Health Service Ministry of Health Abraham Oduro MBChB PhD FGCP Director Location and Contacts UpperUpper EastEast RegionRegion NavrongoNavrongo DSSDSS areaarea Kassena-NankanaKassena-Nankana DistrictDistrict GG HH AA NN AA GhanaGhana 0 25 50 Kilom etre 000 505050 100100100 KilometreKilometreKilometre • Behind War Memorial Hospital, Navrongo • Post Office Box 114, Navrongo , Ghana • Email: [email protected] • Website: www.navrongo-hrc.org Background History • Started in 1998 as Field station for the Ghana Vitamin A Supplementation Trial • Upgraded in 1992 into Health Service Research Centre by Ministry of Health • 1n 2009 became part of R & D Division of the Ghana Health Service Current Affiliations • Currently is One of Three such Centres in Ghana • All under Ghana Health Service, Ministry of Health Vision statement • To be a centre of excellence for the conduct of high quality research and service delivery for national and international health policy development . Mission statement • To undertake health research and service delivery in major national and international health problems with the aim of informing policy for the improvement of health. 1988 - 1992 •Ghana Vitamin A •Navrongo Health Research Supplementation Trial, Centre •(Ghana VAST) • (NHRC-GHS) Prof David Ross Prof Fred Binka Structure and Affiliations Ministry of Health, Ghana Ghana Health Service Council Navrongo Health Research Centre Ghana Health Service (Northern belt) Research & Development Division Kintampo Health Research -

Potential Impact of Large Scale Abstraction on the Quality Of

Land Degradation in the Sudan Savanna of Ghana: A Case Study in the Bawku Area J. K. Senayah1*, S. K. Kufogbe2 and C. D. Dedzoe1 1CSIR-Soil Research Institute, Kwadaso-Kumasi, Ghana 2Department of Geography and Resource Development, University of Ghana, Legon *Corresponding author Abstract The study was carried out in the Bawku area, which is located within the Sudan savanna zone. The study examined the physical environment, human factor and the interactions between them so as to establish the degree and extent of land degradation in the Bawku area. Six rural settlements around Bawku were studied with data on soils collected along transects. Socio-economic information was collected by interviewing key informants and through the administration of questionnaires. Land degradation in the area is the result of interaction between the physical and human environments. Physical environmental characteristics influencing land degradation include soil texture, topography and rainfall. The soils in the study area are developed over granite and Birrimian phyllite. In the granitic areas soil texture is an important factor, while in the Birrimian area, it is the steep nature of the terrain that induces erosion. The granitic soils are characteristically sandy and, as such, highly susceptible to erosion. Topsoil (10–30 cm) sand contents of three major soils developed over granite are over 80%. Severe erosion has reduced topsoil thickness by over 30% within a period of 24 years. Rainfall, though generally low (< 1000 mm), falls so intensely to break down soil aggregates thus accelerating erosion. Other observed indicators of land degradation include sealed and compacted topsoils, stones, gravel, concretions and iron pan. -

Lessons Learned from Scaling up a Community-Based Health Program in the Upper East Region of Northern Ghana

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Lessons learned from scaling up a community-based health program in the Upper East Region of northern Ghana John Koku Awoonor-Williams,a Elias Kavinah Sory,b Frank K Nyonator,b James F Phillips,c Chen Wang,c Margaret L Schmittc The original CHPS model deployed nurses to the community and engaged local leaders, reducing child mortality and fertility substantially. Key scaling-up lessons: (1) place nurses in home districts but not home villages, (2) adapt uniquely to each district, (3) mobilize local resources, (4) develop a shared project vision, and (5) conduct ‘‘exchanges’’ so that staff who are initiating operations can observe the model working in another setting, pilot the approach locally, and expand based on lessons learned. ABSTRACT Ghana’s Community-Based Health Planning and Service (CHPS) initiative is envisioned to be a national program to relocate primary health care services from subdistrict health centers to convenient community locations. The initiative was launched in 4 phases. First, it was piloted in 3 villages to develop appropriate strategies. Second, the approach was tested in a factorial trial, which showed that community-based care could reduce childhood mortality by half in only 3 years. Then, a replication experiment was launched to clarify appropriate activities for implementing the fourth and final phase—national scale up. This paper discusses CHPS progress in the Upper East Region (UER) of Ghana, where the pace of scale up has been much more rapid than in the other 9 regions of the country despite -

Trends in Religious Affiliation Among the Kassena-Nankana of Northern Ghana: Are Switching Patterns Identical by Gender?

Trends in Religious Affiliation Among the Kassena-Nankana of Northern Ghana: Are Switching Patterns Identical by Gender? Henry V. Doctor,1 Evelyn Sakeah,2 and James F. Phillips3 1,2 Navrongo Health Research Centre, P.O. Box 114, Navrongo, Upper East Region, Ghana 3 Population Council, Policy Research Division, One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA. Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Extended Abstract Introduction The practice and rites of traditional religion among the Kassena-Nankana people of northern Ghana are common and extremely significant. Every village has soothsayers who guide ancestral worship and every compound has a shrine for making sacrifices to ancestral spirits (Adongo, Phillips, and Binka 1998). Christianity among the Kassena-Nankana is gaining prominence whereas Islam is also finding its way to the people. However, traditional religion has been practiced for a long time among the Kassena-Nankana compared with Christianity and Islam. In this paper, we examine trends in religious affiliation in Kassena- Nankana District (KND) of northern Ghana between 1995 and 2003. Particularly, we seek to find out the extent to which women and men are switching their religions. Our hypothesis is that there are more people switching from traditional religion to Christianity than is the reverse or to Islam. Research on religious trends in KND is much needed and useful in understanding the factors that are influencing social and demographic changes in KND. For example, recent demographic trends show that fertility is declining and contraceptive use is increasing (Debpuur et al. 2002). Of late, there has been a growing significance of studies dealing with religion in the life of contemporary Africans. -

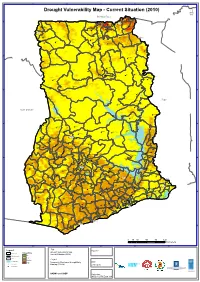

Drought Vulnerability

3°0'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°0'0" 1°0'0"E Drought Vulnerability Map - Current Situation (2010) ´ Burkina Faso Pusiga Bawku N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Gwollu Paga ° 1 1 1 1 Zebilla Bongo Navrongo Tumu Nangodi Nandom Garu Lambusie Bolgatanga Sandema ^_ Tongo Lawra Jirapa Gambaga Bunkpurugu Fumbisi Issa Nadawli Walewale Funsi Yagaba Chereponi ^_Wa N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 0 1 1 Karaga Gushiegu Wenchiau Saboba Savelugu Kumbungu Daboya Yendi Tolon Sagnerigu Tamale Sang ^_ Tatale Zabzugu Sawla Damongo Bole N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 9 9 Bimbila Buipe Wulensi Togo Salaga Kpasa Kpandai Côte d'Ivoire Nkwanta Yeji Banda Ahenkro Chindiri Dambai Kintampo N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 8 Sampa 8 Jema Nsawkaw Kete-krachi Kajeji Atebubu Wenchi Kwame Danso Busunya Drobo Techiman Nkoranza Kadjebi Berekum Akumadan Jasikan Odumase Ejura Sunyani Wamfie ^_ Dormaa Ahenkro Duayaw Nkwanta Hohoe Bechem Nkonya Ahenkro Mampong Ashanti Drobonso Donkorkrom Nkrankwanta N N " Tepa Nsuta " 0 Va Golokwati 0 ' Kpandu ' 0 0 ° Kenyase No. 1 ° 7 7 Hwediem Ofinso Tease Agona AkrofosoKumawu Anfoega Effiduase Adaborkrom Mankranso Kodie Goaso Mamponteng Agogo Ejisu Kukuom Kumasi Essam- Debiso Nkawie ^_ Abetifi Kpeve Foase Kokoben Konongo-odumase Nyinahin Ho Juaso Mpraeso ^_ Kuntenase Nkawkaw Kpetoe Manso Nkwanta Bibiani Bekwai Adaklu Waya Asiwa Begoro Asesewa Ave Dapka Jacobu New Abirem Juabeso Kwabeng Fomena Atimpoku Bodi Dzodze Sefwi Wiawso Obuasi Ofoase Diaso Kibi Dadieso Akatsi Kade Koforidua Somanya Denu Bator Dugame New Edubiase ^_ Adidome Akontombra Akwatia Suhum N N " " 0 Sogakope 0 -

The Navrongo Experiment in Ghana James F Phillips,A Ayaga a Bawah,A & Fred N Binka B

Accelerating reproductive and child health programme impact with community-based services: the Navrongo experiment in Ghana James F Phillips,a Ayaga A Bawah,a & Fred N Binka b Objective To determine the demographic and health impact of deploying health service nurses and volunteers to village locations with a view to scaling up results. Methods A four-celled plausibility trial was used for testing the impact of aligning community health services with the traditional social institutions that organize village life. Data from the Navrongo Demographic Surveillance System that tracks fertility and mortality events over time were used to estimate impact on fertility and mortality. Results Assigning nurses to community locations reduced childhood mortality rates by over half in 3 years and accelerated the time taken for attainment of the child survival Millennium Development Goal (MDG) in the study areas to 8 years. Fertility was also reduced by 15%, representing a decline of one birth in the total fertility rate. Programme costs added US$ 1.92 per capita to the US$ 6.80 per capita primary health care budget. Conclusion Assigning nurses to community locations where they provide basic curative and preventive care substantially reduces childhood mortality and accelerates progress towards attainment of the child survival MDG. Approaches using community volunteers, however, have no impact on mortality. The results also demonstrate that increasing access to contraceptive supplies alone fails to address the social costs of fertility regulation. Effective deployment of volunteers and community mobilization strategies offsets the social constraints on the adoption of contraception. The research in Navrongo thus demonstrates that affordable and sustainable means of combining nurse services with volunteer action can accelerate attainment of both the International Conference on Population and Development agenda and the MDGs. -

FINAL REPORT ASSESSMENT of LOW-COST PRIVATE SCHOOLS in Ftf/RING II

FINAL REPORT ASSESSMENT OF LOW-COST PRIVATE SCHOOLS IN FtF/RING II DISTRICTS IN NORTHERN GHANA November 11, 2019 This report was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by the USAID/WA ASSESS Project. FINAL REPORT ASSESSMENT OF LOW-COST PRIVATE SCHOOLS (LCPSs) IN THE FEED THE FUTURE (FtF) /RESILIENCY IN NORTHERN GHANA (RING II) DISTRICTS IN NORTHERN GHANA Prepared by: USAID/WA Analytical Support Services and Evaluations for Sustainable Systems (ASSESS) Submitted by: Mr. Fedelis Dadzie, Chief of Party, USAID/WA ASSESS Team of Experts: Dr. Leslie Casely-Hayford, Team Leader Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono, EGRA/EGMA Learning Specialist Mrs. Millicent Kaleem, Private Sector Specialist Mr. Jones Agyapong Frimpong, Data Collection and Analysis Expert DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. ii | REPORT - ASSESSMENT OF LCPS IN 17 FTF/RING II DISTRICTS IN NORTHERN GHANA CONTENTS CONTENTS iii TABLES v FIGURES v ACRONYMS vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1.0 BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE 5 1.1 BACKGROUND 5 1.2 PURPOSE 5 2.0 METHODOLOGY 7 2.1 GENERAL ASSESSMENT APPROACH 7 2.2 LIMITATIONS 9 3.0 KEY FINDINGS 11 3.1 SUPPLY AND DEMAND TRENDS FOR LCPSs IN NORTHERN GHANA 11 3.1.1 Supply Trends 11 3.1.2 Demand Trends 13 3.2 EFFECTIVENESS OF LCPSs IN THE FTF/RING II DISTRICTS 16 3.2.1 Management and Leadership of LCPSs 16 3.2.2 Business Model and Sustainability of LCPSs 19 3.2.2.1 -

University of G Institute of African Studies 3U C B

UNIVERSITY OF G INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES 18 JUN1969 DEVEL0PMEN1 MUDIES "W 91/ 3 ) W O Jt. LIBRARY 3UCBAJ IS TER 1966 UNIVERSITY OF GHANA INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES RESEARCH REVIEW VOL. 3 NO.1 MICHAELMAS TERM 1966 RESEARCH REVIEW CONTENTS INSTITUTE NEWS Staff......................... • • • p. 1 LONG ARTICLE African Studies in Germany, Past and Present.................... p. 2 PRO JECT REPORTS The Ashanti Research Project................ P*|9 Arabic Manuscripts........... ............. .................................. p .19 INDIVIDUAL RESEARCH REPORTS A Study in Urbanization - Progress report on Obuasi Project.................................................................... p.42 A Profile on Music and movement in the Volta Region Part I . ............................................. ........................ p.48 Choreography and the African Dance. ........................ p .53 LIBRARY AND MUSEUM REPORTS Seminar Papers by M .A . Students. .................. p .60 Draft Papers................................................... ........ p .60 Books donated to the Institute of African Studies............. p .61 Pottery..................................................................... p. 63 NOTES A note on a Royal Genealogy............................... .......... p .71 A note on Ancestor Cult in Ghana ................. p .74 Birth rites of the Akans ..................................... p.78 The Gomoa Otsew Trumpet Set........... ............. ............. p.82 ******** THE REVIEW The regular inflow of letters from readers