FINAL REPORT ASSESSMENT of LOW-COST PRIVATE SCHOOLS in Ftf/RING II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Ghana Composite Budget of Mion District Assembly for the 2016

REPUBLIC OF GHANA COMPOSITE BUDGET OF MION DISTRICT ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2016 FISCAL YEAR Mion District Assembly Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Background of Mion District Assembly 4 LOCATION AND SIZE 4 DISTRICT ECONOMY 4 UTILITIES 4 WATER 5 EDUCATION 5 HEALTH 5 KEY ISSUES WITHIN THE DISTRICT 5 KEY STRATEGIES 6 VISION AND MISSION STATEMENTS 6 BROAD GOAL 6 Financial Performance –Revenue (IGF only) 7 Financial Performance –Revenue (All revenue sources) 8 Financial Performance –Revenue (All departments) 9 Mion District Assembly Page 2 Financial Performance –Expenditure by departments 10 2015 Non-financial Performance by departments (By sectors) 11 Summary of commitments 12 2016 Revenue projections- IGF only 13 Revenue sources and mobilization strategies 14 2016 Revenue projections- All revenue sources 15 2016 Expenditure projections 16 Summary of expenditure budget by departments, Item and funding source 17 Summary of expenditure budget by departments, Item and funding source 18 Projections and Programmes for 2016 and corresponding costs and justification 19 Projections and Programmes for 2016 and corresponding costs and justification 20 Projections and Programmes for 2016 and corresponding costs and justification 21 Projections and Programmes for 2016 and corresponding costs and justification 22 Projections and Programmes for 2016 and corresponding costs and justification 23 Projections and Programmes for 2016 and corresponding costs and justification 24 Projections and Programmes for 2016 and corresponding costs and justification 25 Mion District Assembly Page 3 MION DISTRICT ASSEMBLY Narrative out line INTRODUCTION Name of the District LI that established the District Population District Economy- Agric, Road, Education Health, Environment, Tourism. Key issues Vision and Mission Objective in line with GSGDA II FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE REVENUE FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE EXPENDITURE Mion District Assembly Page 4 BACKGROUND OF MION DISTRICT The Mion District is one of the newly created Districts in the Northern Region. -

Thesis.Pdf (8.305Mb)

Faculty of Humanities, and Social Science and Education BETWEEN ALIENATION AND BELONGING IN NORTHERN GHANA The voices of the women in the Gambaga ‘witchcamp’ Larry Ibrahim Mohammed Thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies June 2020 i BETWEEN ALIENATION AND BELONGING IN NORTHERN GHANA The voices of the women in the Gambaga ‘witchcamp’ By Larry Ibrahim Mohammed Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education UIT-The Arctic University of Norway Spring 2020 Cover Photo: Random pictures from the Kpakorafon in Gambaga Photos taken by: Larry Ibrahim Mohammed i ii DEDICATION To my parents: Who continue to support me every stage of my life To my precious wife: Whose love and support all the years we have met is priceless. To my daughters Naeema and Radiya: Who endured my absence from home To all lovers of peace and advocates of social justice: There is light at the end of the tunnel iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to a lot of good people whose help has been crucial towards writing this research. My supervisor, Michael Timothy Heneise (Assoc. Professor), has been a rock to my efforts in finishing this thesis. I want to express my profound gratitude and thanks to him for his supervision. Our video call sessions within the COVID-19 pandemic has been of help to me. Not least, it has helped to get me focused in those stressful times. Michael Heneise has offered me guidance through his comments and advice, shaping up my rough ideas. Any errors in judgement and presentation are entirely from me. -

Volta-Hycos Project

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANISATION Weather • Climate • Water VOLTA-HYCOS PROJECT SUB-COMPONENT OF THE AOC-HYCOS PROJECT PROJECT DOCUMENT SEPTEMBER 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………….v 1 WORLD HYDROLOGICAL CYCLE OBSERVING SYSTEM (WHYCOS)……………1 2. BACKGROUNG TO DEVELOPMENT OF VOLTA-HYCOS…………………………... 3 2.1 AOC-HYCOS PILOT PROJECT............................................................................................... 3 2.2 OBJECTIVES OF AOC HYCOS PROJECT ................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 General objective........................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.2 Immediate objectives .................................................................................................................. 3 2.3 LESSONS LEARNT IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AOC-HYCOS BASED ON LARGE BASINS......... 4 3. THE VOLTA BASIN FRAMEWORK……………………………………………………... 7 3.1 GEOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS....................................................................................................... 7 3.2 COUNTRIES OF THE VOLTA BASIN ......................................................................................... 8 3.3 RAINFALL............................................................................................................................. 10 3.4 POPULATION DISTRIBUTION IN THE VOLTA BASIN.............................................................. 11 3.5 SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS........................................................................................... -

Report British Togoland

c. 452 (b). M. 166 (b). 1925. VI. Geneva, September 3rd, 1925. REPORTS OF MANDATORY POWERS Submitted to the Council of the League of Nations in Accordance with Article 2 2 of the Covenant and considered by the Permanent Mandates Commission at its Sixth Session (June-July 1 9 2 5 J. VI REPORT BY HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT ON THE ADMINISTRATION UNDER MANDATE OF BRITISH TOGOLAND FOR THE YEAR 1924 SOCIÉTÉ DES NATIONS — LEAGUE OF NATIONS GENÈVE — 1925 ---- GENEVA NOTES BY THE SECRETARIAT OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS This edition of the reports submitted to the Council of the League of Nations by the Mandatory Powers under Article 22 of the Covenant is published in exe cution of the following resolution adopted by the Assembly on September 22nd, 1924, at its Fifth Session : “ The Assembly . requests that the reports of the Mandat ory Powders should be distributed to the States Members of the League of Nations and placed at the disposal of the public wrho may desire to purchase them. ” The reports have generally been reproduced as received by the Secretariat. In certain cases, however, it has been decided to omit in this new edition certain legislative and other texts appearing as annexes, and maps and photographs contained in the original edition published by the Mandatory Power. Such omissions are indicated by notes by the Secretariat. The annual report on the administration of Togoland under British mandate for the year 1924 was received by the Secretariat on June 15th, 1925, and examined by the Permanent Mandates Commission on July 6th, 1925, in the presence of the accredited representative of the British Government, Captain E. -

Human Rights Violations and Accusations of Witchcraft in Ghana Sara Pierre ABOUT CHRLP

INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS INTERNSHIP PROGRAM | WORKING PAPER SERIES VOL 6 | NO. 1 | FALL 2018 Human Rights Violations and Accusations of Witchcraft in Ghana Sara Pierre ABOUT CHRLP Established in September 2005, the Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) was formed to provide students, professors and the larger community with a locus of intellectual and physical resources for engaging critically with the ways in which law affects some of the most compelling social problems of our modern era, most notably human rights issues. Since then, the Centre has distinguished itself by its innovative legal and interdisciplinary approach, and its diverse and vibrant community of scholars, students and practitioners working at the intersection of human rights and legal pluralism. CHRLP is a focal point for innovative legal and interdisciplinary research, dialogue and outreach on issues of human rights and legal pluralism. The Centre’s mission is to provide students, professors and the wider community with a locus of intellectual and physical resources for engaging critically with how law impacts upon some of the compelling social problems of our modern era. A key objective of the Centre is to deepen transdisciplinary — 2 collaboration on the complex social, ethical, political and philosophical dimensions of human rights. The current Centre initiative builds upon the human rights legacy and enormous scholarly engagement found in the Universal Declartion of Human Rights. ABOUT THE SERIES The Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) Working Paper Series enables the dissemination of papers by students who have participated in the Centre’s International Human Rights Internship Program (IHRIP). -

The Northern Territories of the Gold Coast1

344 THE NORTHERN TERRITORIES OF THE GOLD COAST1 " THE Northern Territories of the Gold Coast " is the name that was given in 1897 to that portion of the Gold Coast Protectorate which lies to the North of Ashanti proper. In those days the Southern Boundary was roughly described as being the 8th parallel of latitude; but in 1906 this was changed and the Black Volta River became the Southern Boundary to a certain point West of Yeji, from whence a line to the River Pru was taken so as to include Prang and Yeji in the Northern Territories, the Pru River being taken as the boundary to its junction with the River Volta, the junction being 8 miles east by road from Yeji. Up to this point both banks of the River Volta are English, but a little lower down, the Dakar River from the north joins the River Volta; and, the Dakar forming for some distance the eastern boundary between the Protectorate and Togo- land, the Volta River continues to do so from the junction to about 120 miles from the mouth of the River. The waterway is entirely English, and the left bank forms the boundary in the higher reaches between Ashanti and Togoland and in the lower reaches between the Colony and Togoland. Beyond this point the boundary takes an easterly direction and both banks become wholly English, the country on the east being known as " The Trans-Volta Province." The boundary on the east of the Protectorate follows the Dakar for some distance north of Salaga and then becomes a beaconed line till it meets the French boundary in the north, laid down so as to leave the country under the King of Mamprusi who resides near Gambaga to the English, and 1 A Lecture given before the Society on Friday, 19th June, 1908. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2007 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2007, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 51.500 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

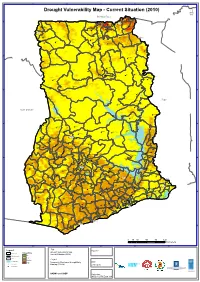

Drought Vulnerability

3°0'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°0'0" 1°0'0"E Drought Vulnerability Map - Current Situation (2010) ´ Burkina Faso Pusiga Bawku N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Gwollu Paga ° 1 1 1 1 Zebilla Bongo Navrongo Tumu Nangodi Nandom Garu Lambusie Bolgatanga Sandema ^_ Tongo Lawra Jirapa Gambaga Bunkpurugu Fumbisi Issa Nadawli Walewale Funsi Yagaba Chereponi ^_Wa N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 0 1 1 Karaga Gushiegu Wenchiau Saboba Savelugu Kumbungu Daboya Yendi Tolon Sagnerigu Tamale Sang ^_ Tatale Zabzugu Sawla Damongo Bole N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 9 9 Bimbila Buipe Wulensi Togo Salaga Kpasa Kpandai Côte d'Ivoire Nkwanta Yeji Banda Ahenkro Chindiri Dambai Kintampo N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 8 Sampa 8 Jema Nsawkaw Kete-krachi Kajeji Atebubu Wenchi Kwame Danso Busunya Drobo Techiman Nkoranza Kadjebi Berekum Akumadan Jasikan Odumase Ejura Sunyani Wamfie ^_ Dormaa Ahenkro Duayaw Nkwanta Hohoe Bechem Nkonya Ahenkro Mampong Ashanti Drobonso Donkorkrom Nkrankwanta N N " Tepa Nsuta " 0 Va Golokwati 0 ' Kpandu ' 0 0 ° Kenyase No. 1 ° 7 7 Hwediem Ofinso Tease Agona AkrofosoKumawu Anfoega Effiduase Adaborkrom Mankranso Kodie Goaso Mamponteng Agogo Ejisu Kukuom Kumasi Essam- Debiso Nkawie ^_ Abetifi Kpeve Foase Kokoben Konongo-odumase Nyinahin Ho Juaso Mpraeso ^_ Kuntenase Nkawkaw Kpetoe Manso Nkwanta Bibiani Bekwai Adaklu Waya Asiwa Begoro Asesewa Ave Dapka Jacobu New Abirem Juabeso Kwabeng Fomena Atimpoku Bodi Dzodze Sefwi Wiawso Obuasi Ofoase Diaso Kibi Dadieso Akatsi Kade Koforidua Somanya Denu Bator Dugame New Edubiase ^_ Adidome Akontombra Akwatia Suhum N N " " 0 Sogakope 0 -

12. Mion District Profile

MION Feed the Future Ghana District Profile Series - February 2017 - Issue 1 DISTRICT PROFILE CONTENT Mion is one of the districts in the Northern Region. The district shares boundaries with the Tamale Metropolis, Savelugu Municipal and Nanton District to the west, 1. Cover Page Yendi Municipal to the east, Nanumba North and East 2. USAID Project Data Gonja districts to the south and Gushegu and Karaga districts to the north. The district covers a total land size 3. Agriculture Data of 2714.1 sq. km and has a population of 91,216 out of which 45,895 are females and 45,321 are males. The 4. Health, Nutrition and Sanitation average household size in the district is 6.9 members. The boxes below contain relevant economic indicators 5. Demographic and Weather Data such as per capita expenditure and poverty prevalence 6. Discussion Questions for a better understanding of its development. Poverty Prevalence 27.0 % Daily per capita expenditure 3.28 USD Households with moderate or severe hunger 13.8% Household Size 6.9 members Poverty Depth 15.4 % Total Population of the Poor 24,628 1 USAID PROJECT DATA This section contains data and information related to USAID sponsored interventions in Mion Table 1: USAID Projects Info, Mion, 2014-2016 Mion had a small number of beneficiaries* Beneficiaries Data 2014 2015 2016 throughout 2014—2016. Ten(10) demo Direct Beneficiaries 486 463 964 Male 410 308 561 plots have been established to provide Female 76 155 403 training about new technologies to the Undefined 0 beneficiaries and no nucleus farmer is Demoplots 3 7 Male 2 operating in the area. -

Religion and Human Rights of Women and Children at The

RELIGION AND HUMAN RIGHTS OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN AT THE GAMBAGA WITCH CAMP IN THE NORTHERN REGION OF GHANA. BY PRINCE OHENE BEKOE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES, KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES. JULY, 2016. i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation is my own work towards the Master of Philosophy in Religious Studies and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the university, except where the due acknowledgement has been made in the text. ……………………………… …………………………… Bekoe Prince Ohene Date (PG1956014) I endorse the declaration by the student and I have approved the final dissertation for assessment. ……………………………… …………………………… Rev. Dr. Atiemo Ofori Abamfo Date (Supervisor) I endorse the declaration by the student and I have approved the final dissertation for assessment. ………………………….. ……………………………… Rev. Fr. Dr. Francis Appiah-Kubi Date (Head of Department) ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the Almighty God who gave me everything I have and my parents, Mr. and Mrs. Kumi Bekoe. I also dedicate this work to my siblings Emmanuel, Jemimah, and Frank. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am grateful to God for His wisdom, strength, favor, protection, love and mercy that has encapsulated me unto completing this work successfully. I sincerely thank my project supervisor, Rev. Dr. Atiemo Ofori Abamfo for spending his precious time in analyzing the write-up from the beginning through to the end. -

Ministry of Health

REPUBLIC OF GHANA MEDIUM TERM EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK (MTEF) FOR 2021-2024 MINISTRY OF HEALTH PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES For 2021 Transforming Ghana Beyond Aid REPUBLIC OF GHANA Finance Drive, Ministries-Accra Digital Address: GA - 144-2024 MB40, Accra - Ghana +233 302-747-197 [email protected] mofep.gov.gh Stay Safe: Protect yourself and others © 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system or Observe the COVID-19 Health and Safety Protocols transmitted in any or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Ministry of Finance Get Vaccinated MINISTRY OF HEALTH 2021 BUDGET ESTIMATES The MoH MTEF PBB for 2021 is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh ii | 2021 BUDGET ESTIMATES Contents PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH ................................ 2 1. NATIONAL MEDIUM TERM POLICY OBJECTIVES ..................................................... 2 2. GOAL ............................................................................................................................ 2 3. VISION .......................................................................................................................... 2 4. MISSION........................................................................................................................ 2 5. CORE FUNCTIONS ........................................................................................................ 2 6. POLICY OUTCOME -

MV Baseline Summary Report

UK Data Archive Study Number 8361 – Millennium Village Impact Evaluation in Northern Ghana, 2012-2016 MILLENNIUM VILLAGES IMPACT EVALUATION, BASELINE SUMMARY REPORT Date: February 2014 By Masset, Jupp, Korboe, Dogbe, and Barnett Page | 1 MILLENNIUM VILLAGES IMPACT EVALUATION, BASELINE SUMMARY REPORT, FEBRUARY 2014 Acknowledgements This report has been prepared by the team for the impact evaluation of the Millennium Villages Project. The team is composed of staff from Itad, the Institute of Development Studies, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and PDA-Ghana. The team is fully independent of the Earth Institute and the Millennium Promise. The principal authors of this report are Dr Edoardo Masset, Dr Dee Jupp, Dr David Korboe, Tony Dogbe, and Dr Chris Barnett. The team is nonetheless very grateful to all the researchers that have assisted with data collection, the staff at DFID, and everyone else that has provided support, information, and comments – including the work of the Earth Institute during the enumeration phase. The findings of this report are the full responsibility of the authors, and any views contained in this report do not necessarily represent those of DFID or of the people consulted. The first drafts of this report were edited and proofread by Pippa Lord, Jane Stanton, Alice Parsons, and Kelsy Nelson. The final copy was proofread by Caitlin McCann. Citation Masset, E., Jupp, D., Korboe, D., Dogbe, T., & Barnett, C. 2014. Millennium Villages Impact Evaluation, Baseline Summary Report. Itad, Hove. Page |