By RON THOMAS San Francisco Chronicle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bee Gee News March 29, 1945

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 3-29-1945 Bee Gee News March 29, 1945 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "Bee Gee News March 29, 1945" (1945). BG News (Student Newspaper). 731. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/731 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. i Boa GOB A/ewd Zi '***** v v ' Official' Student Publication ' .1 fUkSKW BOWLING GREKN, OHIO. THURSDAY, MARCH 29, 1945 NO. 18 Falcons Finish Greatest Basketball Season Tonight With Bee Gee News Photographer at Garden Game .. anriT 4 r. 1 • r- 1 Meet NYU After Losing Final f> 3 ' r ' " ^BASKETBALL A,, Of Garden Meet to DePaul -VITATION FINALS NBi 4B l a, , n BOWUHC GREEN ' Bowling Green's Falcons tonight will finish their most nr PAUL » BU"*-" inljyr successful season in history when they meet New York Univer- i sity in a consolation basketball game. i«;i AND J ST JQH''.-?,. Defeated Monday in the finals of the Madison Square Gardens Invitational tournament by DePaul of Chicago by a -tUSfiA BUXING score of 71-64, Bowling Green's team is one of the four best r Kiu ' " in the country. Last year the Falcons also advanced to the NfiVA : BAKSI m) tournament for the first time but were defeated in the first . -

1997 Induction Class Larry Bird, Indiana State Hersey Hawkins

1997 Induction Class Institutional Great -- Carole Baumgarten, Drake Larry Bird, Indiana State Lifetime Achievement -- Duane Klueh, Indiana State Hersey Hawkins, Bradley Paul Morrison Award -- Roland Banks, Wichita State Coach Henry Iba, Oklahoma A&M Ed Macauley, Saint Louis 2007 Induction Class Oscar Robertson, Cincinnati Jackie Stiles, Missouri State Dave Stallworth, Wichita State Wes Unseld, Louisville 2008 Induction Class Paul Morrison Award -- Paul Morrison, Drake Bob Harstad, Creighton Kevin Little, Drake 1998 Induction Class Ed Jucker, Cincinnati Bob Kurland, Oklahoma A&M Institutional Great -- A.J. Robertson, Bradley Chet Walker, Bradley Lifetime Achievement -- Jim Byers, Evansville Xavier McDaniel, Wichita State Lifetime Achievement -- Jill Hutchison, Illinois State Lifetime Achievement -- Kenneth Shaw, Illinois State Paul Morrison Award -- Mark Stillwell, Missouri State Institutional Great -- Doug Collins, Illinois State Paul Morrison Award -- Dr. Lee C. Bevilacqua, Creighton 2009 Induction Class Junior Bridgeman, Louisville 1999 Induction Class John Coughlan, Illinois State Antoine Carr, Wichita State Eddie Hickey, Creighton/Saint Louis Joe Carter, Wichita State Institutional Great -- Lorri Bauman, Drake Melody Howard, Missouri State Lifetime Achievement -- John Wooden, Indiana State Holli Hyche, Indiana State Lifetime Achievement -- John L. Griffith, Drake Paul Morrison Award -- Glen McCullough, Bradley Paul Morrison Award -- Jimmy Wright, Missouri State 2000 Induction Class 2010 Induction Class Cleo Littleton, Wichita State -

SCR003S01 Compared with SCR003

SCR003S01 compared with SCR003 {deleted text} shows text that was in SCR003 but was deleted in SCR003S01. inserted text shows text that was not in SCR003 but was inserted into SCR003S01. DISCLAIMER: This document is provided to assist you in your comparison of the two bills. Sometimes this automated comparison will NOT be completely accurate. Therefore, you need to read the actual bills. This automatically generated document could contain inaccuracies caused by: limitations of the compare program; bad input data; or other causes. Senator Jani Iwamoto proposes the following substitute bill: CONCURRENT RESOLUTION HONORING WATARU MISAKA 2020 GENERAL SESSION STATE OF UTAH Chief Sponsor: Jani Iwamoto House Sponsor: ____________ LONG TITLE General Description: This concurrent resolution honors Wataru Misaka. Highlighted Provisions: This resolution: < honors the late Wataru "Wat" Misaka, who was the first person of color to play in what is now the National Basketball Association; and < recognizes Mr. Misaka's athletic abilities and contributions to college and professional basketball. Special Clauses: None Be it resolved by the Legislature of the state of Utah, the Governor concurring therein: - 1 - SCR003S01 compared with SCR003 WHEREAS, Wataru "Wat" Misaka, who broke the color barrier by being the first person of color to play in what is now the National Basketball Association (NBA), died on November {20} 21 , 2019, in Salt Lake City at the age of 95; WHEREAS, born and raised in Ogden, Wat Misaka was a 5-foot-7-inch tall Japanese American whose basketball career began at Ogden High School where he led his team to the 1940 state championship and regional championship in 1941; WHEREAS, in 1942, his Weber Junior College basketball team won the Intermountain Collegiate Athletic Conference (ICAC) junior college title and he was named "most valuable player" of that year's junior college post-season tournament; WHEREAS, in 1943, the Weber Junior College team earned another ICAC title and the college named him "athlete of the year"; WHEREAS, Mr. -

B O X S C O R E a Publication of the Indiana High School Basketball Historical Society IHSBHS Was Founded in 1994 by A

B O X S C O R E A Publication of the Indiana High School Basketball Historical Society IHSBHS was founded in 1994 by A. J. Quigley Jr. (1943-1997) and Harley Sheets for the purpose of documenting and preserving the history of Indiana High School Basketball IHSBHS Officers Publication & Membership Notes President Roger Robison Frankfort 1954 Boxscore is published by the Indiana High School Basketball Vice Pres Cliff Johnson Western 1954 Historical Society (IHSBHS). This publication is not copyrighted and may be reproduced in part or in full for circulation anywhere Webmaster Jeff Luzadder Dunkirk 1974 Indiana high school basketball is enjoyed. Credit given for any Treasurer Rocky Kenworthy Cascade 1974 information taken from Boxscore would be appreciated. Editorial Staff IHSBHS is a non-profit organization. No salaries are paid to Editor Cliff Johnson Western 1954 anyone. All time spent on behalf of IHSBHS or in producing Boxscore is freely donated by individual members. Syntax Edits Tim Puet Valley, PA 1969 Dues are $8 per year. They run from Jan. 1 – Dec. 31 and Content Edits Harley Sheets Lebanon 1954 include four newsletters. Lifetime memberships are no longer Tech Advisor Juanita Johnson Fillmore, CA 1966 offered, but those currently in effect continue to be honored. Board Members Send dues, address changes, and membership inquiries to IHSBHS, c/o Rocky Kenworthy, 710 E. 800 S., Clayton, IN 46118. E-mail: [email protected] Bill Ervin, John Ockomon, Harley Sheets, Leigh Evans, Cliff All proposed articles & stories should be directed to Johnson, Tim Puet, Roger Robison, Jeff Luzadder, Rocky Cliff Johnson: [email protected] or 16828 Fairburn Kenworthy, Doug Bradley, Curtis Tomak. -

Iplffll. Tubeless Or Tire&Tube

THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. M Billy Meyer Dead at 65; Lead Stands Up MONDAY. APBIL 1, 1957 A-17 Long Famous in Baseball , i Gonzales Quitting Pro Tour . - May Injured - ' • •• As 'v Palmer Wins mEBIIHhhS^^s^hESSHSI KNOXVILLE, Term., April. 1 ¦ In to Heal Hand V9T (VP).—Death has claimed William MONTREAL, April 1 (VP).—Big : wall to pro to give Adam (Billy) Meyer, major turn Gonzales Oonzales, king of profes- some competition, avail- league “manager of the year” Pancho ¦ was not Azalea Tourney sional tennis, today decided to -1 able for comment but it could ; with the underdog Pittsburgh quit Kramer’s troupe after : as any surprise Pirates in 1948 and of the Jack not have come one WILMINGTON, N. C.. April 1 May . best-known minor league man- Its last American match 26. to him. (VP).—Although he outshot only Plagued by a cyst on his racket ; When the American segment ! agers of all time. four of the 24 other money win- hand, Gonzales said: of the tour opened in New Yorl The 65-yfear-old veteran of 46 ners in the Azalea Open golf “Ineed a rest. I’ve been play- February 17, Gonzales was ljl years player, ¦ as manager, scout tournament’s final round, Arnold ing continuously for 18 months > pain and he said that if this and “trouble shooter” died in a Palmer’s 54-hole lead stood up and I want to give my hand a injury not heal, he miglit and i did hospital yesterday of a heart and ” he eased out with a one- chance to heal.” have to quit. -

Downtrodden Yet Determined: Exploring the History Of

DOWNTRODDEN YET DETERMINED: EXPLORING THE HISTORY OF BLACK MALES IN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL AND HOW THE PLAYERS ASSOCIATION ADDRESSES THEIR WELFARE A Dissertation by JUSTIN RYAN GARNER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, John N. Singer Committee Members, Natasha Brison Paul J. Batista Tommy J. Curry Head of Department, Melinda Sheffield-Moore May 2019 Major Subject: Kinesiology Copyright 2019 Justin R. Garner ABSTRACT Professional athletes are paid for their labor and it is often believed they have a weaker argument of exploitation. However, labor disputes in professional sports suggest athletes do not always receive fair compensation for their contributions to league and team success. Any professional athlete, regardless of their race, may claim to endure unjust wages relative to their fellow athlete peers, yet Black professional athletes’ history of exploitation inspires greater concerns. The purpose of this study was twofold: 1) to explore and trace the historical development of basketball in the United States (US) and the critical role Black males played in its growth and commercial development, and 2) to illuminate the perspectives and experiences of Black male professional basketball players concerning the role the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA), collectively considered as the Players Association for this study, played in their welfare and addressing issues of exploitation. While drawing from the conceptual framework of anti-colonial thought, an exploratory case study was employed in which in-depth interviews were conducted with a list of Black male professional basketball players who are members of the Players Association. -

Colgate Seen 176 Reilly Rd 2 Children, 17 and 15

Spring 2010 News and views for the Colgate community scene The Illusion of Sameness Snapshots A Few Minutes with the Rooneys Spring 2010 26 The Illusion of Sameness Retiring professor Jerry Balmuth’s parting parable on our confrontations with difference 30 Snapshots A class documents life at Colgate around the clock scene 36 A Few Minutes with the Rooneys A conversation with America’s “curmudgeon-in-chief” Andy Rooney ’42 and his son, Brian ’74 DEPARTMENTS 3 Message from Interim President Lyle D. Roelofs 4 Letters 6 Work & Play 13 Colgate history, tradition, and spirit 14 Life of the Mind 18 Arts & Culture 20 Go ’gate 24 New, Noted & Quoted 42 The Big Picture 44 Stay Connected 45 Class News 72 Marriages & Unions 73 Births & Adoptions 73 In Memoriam 76 Salmagundi: Puzzle, Rewind, and Slices contest On the cover: Bold brush strokes. Theodora “Teddi” Hofmann ’10 in painting class with Lynette Stephenson, associate professor of art and art history. Photo by Andrew Daddio. Facing page photo by Timothy D. Sofranko. News and views for the Colgate community 1 Contributors Volume XXXIX Number 3 The Scene is published by Colgate University four times a year — in autumn, winter, spring, and summer. The Scene is circulated without charge to alumni, parents, friends, and students. Vice President for Public Relations and Communications Charles Melichar Managing Editor Kate Preziosi ’10 Jerome Balmuth, Award-winning ABC Known for depicting Rebecca Costello (“Back on campus,” pg. Harry Emerson Fosdick News Correspondent many celebrities’ vis- Associate Editor 9, “Broadcasting new Professor of philoso- Brian Rooney ’74 (“A ages, illustrator Mike Aleta Mayne perspectives,” pg. -

Boston Celtics Game Notes

2020-21 Postseason Schedule/Results Boston Celtics (1-3) at Brooklyn Nets (3-1) Date Opponent Time/Results (ET) Record Postseason Game #5/Road GaMe #3 5/22 at Brooklyn L/93-104 0-1 5/25 at Brooklyn L/108-130 med0-2 Barclays Center 5/28 vs. Brooklyn W/125-119 1-2 Brooklyn, NY 5/30 vs. Brooklyn 7:00pm 6/1 at Brooklyn 7:30pm Tuesday, June 1, 2021, 7:30pm ET 6/3 vs. Brooklyn* TBD 6/5 at Brooklyn* TBD TV: TNT/NBC Sports Boston Radio: 98.5 The Sports Hub *if necessary PROBABLE STARTERS POS No. PLAYER HT WT G GS PPG RPG APG FG% MPG F 94 Evan Fournier 6’7 205 4 4 14.8 3.0 1.5 41.3 32.7 F 0 Jayson Tatum 6’8 210 4 4 30.3 5.0 4.5 41.7 36.0 C 13 Tristan Thompson 6’9 254 4 4 10.8 10.0 1.0 63.3 25.6 G 45 Romeo Langford 6’4 215 3 1 6.3 3.0 1.0 30.0 23.7 G 36 Marcus Smart 6’3 220 4 4 18.8 3.8 6.5 49.0 36.0 *height listed without shoes INJURY REPORT Player Injury Status Jaylen Brown Left Scapholunate Ligament Surgery Out Kemba Walker Left Knee Medial Bone Bruise Doubtful Robert Williams Left Ankle Sprain Doubtful INACTIVE LIST (PREVIOUS GAME) Player Jaylen Brown Kemba Walker Robert Williams POSTSEASON TEAM RECORDS Record Home Road Overtime Overall (1-3) (1-1) (0-2) (0-0) Atlantic (1-3) (1-0) (0-2) (0-0) Southeast (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) Central (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) Eastern Conf. -

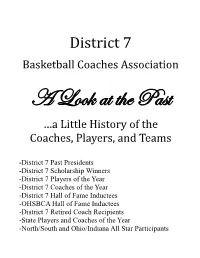

HISTORY of District 7

District 7 Basketball Coaches Association T _ÉÉ~ tà à{x ctáà …a Little History of the Coaches, Players, and Teams -District 7 Past Presidents -District 7 Scholarship Winners -District 7 Players of the Year -District 7 Coaches of the Year -District 7 Hall of Fame Inductees -OHSBCA Hall of Fame Inductees -District 7 Retired Coach Recipients -State Players and Coaches of the Year -North/South and Ohio/Indiana All Star Participants -State Tournament Qualifying Teams and Results Northwest Ohio District Seven Coaches Association Past Presidents Dave Boyce Perrysburg Gerald Sigler Northview Bud Felhaber Clay Bruce Smith Whitmer Betty Jo Hansbarger Swanton Tim Smith Northview Marc Jump Southview Paul Wayne Holgate Dave Krauss Patrick Henry Dave McWhinnie Toledo Christian Kirk Lehman Tinora Denny Shoemaker Northview Northwest Ohio District Seven Coaches Association Scholarship Winners Kim Asmus Otsego 1995 Jason Bates Rogers 1995 Chris Burgei Wauseon 1995 Collin Schlosser Holgate 1995 Kelly Burgei Wauseon 1998 Amy Perkins Woodmore 1999 Tyler Schlosser Holgate 1999 Tim Krauss Archbold 2000 Greg Asmus Otsego 2000 Tyler Meyer Patrick Henry 2001 Brock Bergman Fairview 2001 Ashley Perkins Woodmore 2002 Courtney Welch Wayne Trace 2002 Danielle Reynolds Elmwood 2002 Brett Wesche Napoleon 2002 Andrew Hemminger Oak Harbor 2003 Nicole Meyer Patrick Henry 2003 Erica Riblet Ayersville 2003 Kate Achter Clay 2004 Michael Graffin Bowling Green 2004 Trent Meyer Patrick Henry 2004 Cody Shoemaker Northview 2004 Nathan Headley Hicksville 2005 Ted Heintschel St. -

50 Anniversary of Syracuse Nationals NBA Championship 50 Anniversary

50th Anniversary of Syracuse Nationals NBA Championship WHEREAS, The Syracuse Nationals joined the National Basketball League (NBL) in the 1946-47 season, and three years later six NBL franchises, including the “Nats” merged with the Basketball Association of America (BAA) to form the National Basketball Association (NBA); and WHEREAS, While the team moved to Philadelphia and became the ‘76ers in 1963, the Syracuse Nationals enjoyed many successful seasons in Syracuse, playing against the Minneapolis Lakers in the NBA’s first championship series in 1950, reaching the NBA Finals in 1954, and winning the NBA Championship in 1955; and WHEREAS, There were many outstanding players on the Syracuse Nationals basketball team, several of whom made indelible marks on the history of basketball, and are present here today: Dolph Schayes, who was the first star of the Syracuse Nationals, garnering in his 13 years as a professional basketball player 5 league records and widely regarded as the first true “power forward”; and Earl Lloyd, who in 1950 became the first African-American to play in an NBA game, in 1955 with the Syracuse Nationals he became the first African-American to win an NBA championship, and later went on to distinguish himself in many coaching endeavors; and WHEREAS, It is an honor to recognize today the legacy of the Syracuse Nationals and remember their victorious 1955 NBA Championship. NOW, THEREFORE, I, NICHOLAS J. PIRRO, County Executive of the County of Onondaga and I, MATTHEW J. DRISCOLL, Mayor of the City of Syracuse, do hereby proclaim the twenty-sixth day of March, two thousand five as 50th Anniversary of the Syracuse Nationals NBA Championship in the County of Onondaga and the City of Syracuse IN WITNESS WHEREOF, we have hereunto set our hands and caused the Seals of the County of Onondaga and the City of Syracuse to be imprinted this twenty-sixth day of March, two thousand five. -

2010-11 NCAA Men's Basketball Records

Award Winners Division I Consensus All-America Selections .................................................... 2 Division I Academic All-Americans By Team ........................................................ 8 Division I Player of the Year ..................... 10 Divisions II and III Players of the Year ................................................... 12 Divisions II and III First-Team All-Americans By Team .......................... 13 Divisions II and III Academic All-Americans By Team .......................... 15 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By Team ...................................... 16 2 Division I Consensus All-America Selections Division I Consensus All-America Selections 1917 1930 By Season Clyde Alwood, Illinois; Cyril Haas, Princeton; George Charley Hyatt, Pittsburgh; Branch McCracken, Indiana; Hjelte, California; Orson Kinney, Yale; Harold Olsen, Charles Murphy, Purdue; John Thompson, Montana 1905 Wisconsin; F.I. Reynolds, Kansas St.; Francis Stadsvold, St.; Frank Ward, Montana St.; John Wooden, Purdue. Oliver deGray Vanderbilt, Princeton; Harry Fisher, Minnesota; Charles Taft, Yale; Ray Woods, Illinois; Harry Young, Wash. & Lee. 1931 Columbia; Marcus Hurley, Columbia; Willard Hyatt, Wes Fesler, Ohio St.; George Gregory, Columbia; Joe Yale; Gilmore Kinney, Yale; C.D. McLees, Wisconsin; 1918 Reiff, Northwestern; Elwood Romney, BYU; John James Ozanne, Chicago; Walter Runge, Colgate; Chris Earl Anderson, Illinois; William Chandler, Wisconsin; Wooden, Purdue. Steinmetz, Wisconsin; George Tuck, Minnesota. Harold -

History All-Time Coaching Records All-Time Coaching Records

HISTORY ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS REGULAR SEASON PLAYOFFS REGULAR SEASON PLAYOFFS CHARLES ECKMAN HERB BROWN SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT LEADERSHIP 1957-58 9-16 .360 1975-76 19-21 .475 4-5 .444 TOTALS 9-16 .360 1976-77 44-38 .537 1-2 .333 1977-78 9-15 .375 RED ROCHA TOTALS 72-74 .493 5-7 .417 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1957-58 24-23 .511 3-4 .429 BOB KAUFFMAN 1958-59 28-44 .389 1-2 .333 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1959-60 13-21 .382 1977-78 29-29 .500 TOTALS 65-88 .425 4-6 .400 TOTALS 29-29 .500 DICK MCGUIRE DICK VITALE SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT PLAYERS 1959-60 17-24 .414 0-2 .000 1978-79 30-52 .366 1960-61 34-45 .430 2-3 .400 1979-80 4-8 .333 1961-62 37-43 .463 5-5 .500 TOTALS 34-60 .362 1962-63 34-46 .425 1-3 .250 RICHIE ADUBATO TOTALS 122-158 .436 8-13 .381 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT CHARLES WOLF 1979-80 12-58 .171 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT TOTALS 12-58 .171 1963-64 23-57 .288 1964-65 2-9 .182 SCOTTY ROBERTSON REVIEW 18-19 TOTALS 25-66 .274 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1980-81 21-61 .256 DAVE DEBUSSCHERE 1981-82 39-43 .476 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1982-83 37-45 .451 1964-65 29-40 .420 TOTALS 97-149 .394 1965-66 22-58 .275 1966-67 28-45 .384 CHUCK DALY TOTALS 79-143 .356 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1983-84 49-33 .598 2-3 .400 DONNIE BUTCHER 1984-85 46-36 .561 5-4 .556 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1985-86 46-36 .561 1-3 .250 RE 1966-67 2-6 .250 1986-87 52-30 .634 10-5 .667 1967-68 40-42 .488 2-4 .333 1987-88 54-28 .659 14-9 .609 CORDS 1968-69 10-12 .455 1988-89 63-19 .768 15-2 .882 TOTALS 52-60 .464 2-4 .333