Ruth Negga, Breakfast on Pluto, and Invisible Irelands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Kristen Connolly Helps Move 'Zoo' Far Ahead

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad We’ve got you covered! June 23 - 29, 2017 waxahachietx.com U J A M J W C Q U W E V V A H 2 x 3" ad N A B W E A U R E U N I T E D Your Key E P R I D I C Z J Z A Z X C O To Buying Z J A T V E Z K A J O D W O K W K H Z P E S I S P I J A N X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad A C A U K U D T Y O W U P N Y W P M R L W O O R P N A K O J F O U Q J A S P J U C L U L A Co-star Kristen Connolly L B L A E D D O Z L C W P L T returns as the third L Y C K I O J A W A H T O Y I season of “Zoo” starts J A S R K T R B R T E P I Z O Thursday on CBS. O N B M I T C H P I G Y N O W A Y P W L A M J M O E S T P N H A N O Z I E A H N W L Y U J I Z U P U Y J K Z T L J A N E “Zoo” on CBS (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Jackson (Oz) (James) Wolk Hybrids Place your classified Solution on page 13 Jamie (Campbell) (Kristen) Connolly (Human) Population ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Mitch (Morgan) (Billy) Burke Reunited Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and Abraham (Kenyatta) (Nonso) Anozie Destruction Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Dariela (Marzan) (Alyssa) Diaz (Tipping) Point Kristen Connolly helps Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it move ‘Zoo’ far ahead 2 x 3.5" ad 2 x 4" ad 4 x 4" ad 6 x 3" ad 16 Waxahachie Daily Light Cardinals. -

{PDF EPUB} Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha by Roddy Doyle Writing Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha by Roddy Doyle Writing Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha. I started writing Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha in February 1991, a few weeks after the birth of my first child. I'd finished The Van, my third novel, the previous November and I remember being told, more than once, that it was the last book I'd write for a long time, until after the baby, and the other babies, had been fattened and educated. They were joking - I think - the friends who announced my retirement. But it worried me. I was a teacher, and now I was a father. But the other definition I'd only been getting the hang of, novelist, was being nudged aside, becoming a hobby or a memory. So, I started Paddy Clarke to prove to myself that I could - that it was permitted. That there was still room in my life for writing. I don't really remember why I decided to write about a 10-year-old boy, or about that boy in 1968 - I don't remember the decisions. I was 10 in 1968, as is Paddy, and I do remember that I was thinking a lot about my childhood, possibly anticipating my son's future. My parents still lived in the house I'd grown up in. The school I taught in and the surrounding houses had been the fields and building sites that Paddy Clarke plays in. I was aware that my past was very near. But I don't recall a decision. -

NANA FISCHER Hair and Make-Up Artist IATSE Local 706 Fluent in German, Japanese, English and Some French

NANA FISCHER Hair and Make-Up Artist IATSE Local 706 Fluent in German, Japanese, English and some French FILM BUTTER Department Head Make-Up Branded Pictures Entertainment/ The Kaufman Director: Paul A. Kaufman Company Cast: Various MOWGLI Hair and Make-Up Designer and Prosthetics Artist Warner Bros. Studios Director: Andy Serkins Cast: Rohan Chand, Freida Pinto KIN Personal Hair and Make-Up to James Franco 21 Laps Entertainment Directors: Jonathan Baker, Josh Baker AD ASTRA Department Head Make-Up and Hair Designer New Regency Pictures Director: James Gray Cast: Tommy Lee Jones, Donald Sutherland, Liv Tyler, Ruth Negga, Kimberly Elise, Donnie Keshawarz DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET FAR ON FOOT Hair and Make-Up Designer Anonymous Content Director: Gus Van Sant Cast: Joaquin Phoenix, Rooney Mara, Jack Black THE PRETENDERS Hair and Make-Up Designer Pretenders Film Inc Director: James Franco Cast: James Franco, Juno Temple, Jane Levy WHY HIM? Personal Hair and Make-Up to James Franco 21 Laps Entertainment Director: John Hamburg THE DISASTER ARTIST Personal Hair and Make-Up and Prosthetics Artist to Good Universe James Franco Director: James Franco LOST CITY OF Z Hair and Make-Up Designer MICA Entertainment Director: James Gray Charlie Hunnam, Sienna Miller, Robert Pattinson THE LIGHT BETWEEN OCEANS Hair and Make-Up Designer and Personal Hair and DreamWorks SKG Make-Up to Michael Fassbender Director: Derek Cianfrance Cast: Michael Fassbender, Rachel Weisz, Alicia Vikander TRESPASS AGAINST US Personal Hair and Make-Up to Michael Fassbender Potboiler -

Irish Movies for Children: Darby O'gill and the Little People Early

Irish Movies For Children: Darby O’Gill and the Little People Early movie for Sean Connery and made by Walt Disney. Small children sometimes worry about the Banshee. The Secrete of Roan Inish Into the West A bit more mature but still for kids The Troubles: The Informer A John Ford movie made in 1935. It has many of the John Ford (Feeny) cast members except for John Wayne. Odd Man Out Made in 1947 with James Mason in the IRA Shake Hands with the Devil James Cagney linked to the IRA in 1920. Most Cagney movies have some Irish link, particularly if he is with Pat O’Brien. Michael Collins A relatively accurate portrayal of Collins and DeValera but the romance is cumbersome. The Wind that Shakes the Barley A grim portrayal of the War of Independence (1918-22) outside of Dublin. Bloody Sunday A fairly accurate portrayal of Derry (Londonderry) in 1971. Hidden Agenda Speculation of Margaret Thatcher’s shoot to kill policy. Some Mother’s Son Helen Mirren in a portrayal of the “hunger strikes.” In the Name of the Father Daniel Day-Lewis does a remarkable performance of Gerry Conlon who spent 16 years in prison. The prison that is filmed is Kilmainham, built in 1796 and virtually every Irish patriot from 1798 to 1922 spent time there. It is now a museum. Omagh About a bombing in Northern Ireland at the same time as the peace talks were developing. Comedy: The Quiet Man Popular everywhere. I See a Dark Stranger 1948 Somewhere between comedy and drama with Deborah Kerr and Trevor Howard during WW II The Boys and the Girl from County Clare The Matchmaker The Commitments A Roddy Doyle novel The Snapper Another Roddy Doyle novel Waking Ned Devine Leap Year In America The Most Fertile Man in Ireland I believe this can be watched for free on YouTube. -

March of the Mutts! Potential School Split Tops Daphne Social Skills Young Ladies and Men Practice What They’Ve Discussion Been Preached at Ball

COMMUNITY CALENDAR: Ongoing and Upcoming Events, PAGE 39 Blakely Park welcomes visitors with new trail The Courier PAGE 3 INSIDE FEBRUARY 22, 2017 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ March of the Mutts! Potential school split tops Daphne Social skills Young ladies and men practice what they’ve discussion been preached at ball. PAGE 4 By CLIFF McCOLLUM would be better to break [email protected] off and form your own system.” A potential split from Campbell did inform Baldwin County’s school the council they did not system was once again necessarily have to have on the table during last a vote of the public be- week’s Daphne City fore making the decision Council work session, whether to split. as city leaders listened Campbell walked the to the opinion of a local council through the pro- attorney who had helped cess of appointing their other systems navigate own school board and Bridge scores their splits. negotiating the city’s exit Mobile attorney Bob with the county system. This edition’s top Campbell spoke to the “It’s like a huge, hor- players from fi rst to council about his experi- rible divorce,” Campbell third place ences helping the cities said. “You’ve got one PAGE 37 of Saraland, Satsuma party that doesn’t want Mammals of the two and four-legged variety gathered in the streets of Fairhope Saturday and Chickasaw break afternoon for the beloved annual Mystic Mutts of Revelry Mardi Gras Parade. Sponsored the divorce, Baldwin by The Haven, the dog parade has quickly become a favorite event for residents across the away from the Mobile County. -

Breakfast on Pluto

Pathé Pictures and Sony Pictures Classics present Breakfast on Pluto A Neil Jordan Film Running Time : 129 minutes “Oh, serious, serious, serious!” --Patrick “Kitten” Braden East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor International House of Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Angela Gresham. 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-247-2948 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax Visit the Sony Pictures Classics website at www.sonyclassics.com BREAKFAST ON PLUTO Cast PATRICK CILLIAN MURPHY FATHER BERNARD LIAM NEESON CHARLIE RUTH NEGGA IRWIN LAURENCE KINLAN BERTIE STEPHEN REA UNCLE BULGARIA BRENDAN GLEESON PATRICK (10) CONOR McEVOY BILLY HATCHET GAVIN FRIDAY PC WALLIS IAN HART EILY BERGIN EVA BIRTHISTLE MA BRADEN RUTH MCCABE INSP ROUTLEDGE STEVEN WADDINGTON RUNNING BEAR MARK DOHERTY EILY'S BOY SID YOUNG HORSE KILLANE CIARAN NOLAN JACKIE TIMLIN EAMONN OWENS WHITE DOVE TONY DEVLIN MR SILKY STRING BRYAN FERRY LAURENCE (10) SEAMUS REILLY CHARLIE (10) BIANCA O'CONNOR CAROLINE BRADEN CHARLENE McKENNA SQUADDIE (DISCO) JO JO FINN SOLDIER NEIL JACKSON BENNY FEELY PARAIC BREATHNACH BIKER 1 JAMES MCHALE MOSHER LIAM CUNNINGHAM DEAN OWEN ROE HOUSEKEEPER MARY COUGHLAN MRS FEELY MARY REGAN PEEPERS EGAN PAT McCABE MRS HENDERSON CATHERINE POGSON PUNTER 1 GERRY O'BRIEN PUNTER 2 CHRIS McHALLUM BROTHER BARNABAS PETER GOWAN STRIPPER ANTONIA -

Ruth Negga MIGLIOR ATTORE PROTAGONISTA – Joel Edgerton MIGLIOR ATTRICE PROTAGONISTA – Ruth Negga

FOCUS FEATURES PRESENTA UNA PRODUZIONE DI RAINDOG FILMS/BIG BEACH PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIAZIONE CON AUGUSTA FILMS & TRI-STATE PICTURES ★ CANDIDATO PREMIO OSCAR★ ★ CANDIDATO GOLDEN GLOBE ★ MIGLIOR ATTRICE PROTAGONISTA – Ruth Negga MIGLIOR ATTORE PROTAGONISTA – Joel Edgerton MIGLIOR ATTRICE PROTAGONISTA – Ruth Negga LOVING OGNI AMORE DEVE NASCERE LIBERO scritto e diretto da JEFF NICHOLS con Joel Edgerton e Ruth Negga Uscita in sala 16 marzo Distribuzione Ufficio stampa - Studio PUNTOeVIRGOLA Social media & digital PR – NAPIER 2 ★★★★★ The Indipendent «Un film sobrio, ma potente ed esaltante» ★★★★★ Washington Post «Intimo e commovente» «Sobriamente implacabile come i suoi protagonisti» ★★★★★ Los Angeles Times «Negga and Edgerton sono entrambi eccezionali» ★★★★★ Hollywood Reporter «Un grande soggetto trattato in modo infallibilmente intimo» ★★★★★ New York Times «Un film di grande integrità e dolcezza» ★★★★★ Le Monde « Una bella sobrietà che non impedisce l’emozione dei primi piani» ★★★★★ Les InRockuptibles «Nessuna enfasi, né sentimentalismi […] una regia asciutta, di un classicismo rigoroso» 3 CAST ARTISTICO Mildred Ruth Negga Richard Joel Edgerton Sceriffo Brooks Marton Csokas Bernie Cohen Nick Kroll Ganert Terri Abney Raymond Alano Miller Phil Hirschkop Jon Bass Grey Villet Michael Shannon CAST TECNICO Scritto e diretto da Jeff Nichols Prodotto da Ged Doherty, p.g.a. & Colin Firth, p.g.a. Nancy Buirski, p.g.a. Sarah Green, p.g.a. Marc Turtletaub, p.g.a. & Peter Saraf, p.g.a. Produttori esecutivi Brian Kavanaugh-Jones Jack Turner Jared Ian Goldman Direttore della fotografia Adam Stone Responsabile di produzione Chad Keith Montaggio Julie Monroe Costumi Erin Benach Musica David Wingo Casting Francine Maisler, Csa Durata 123 minuti Parzialmente basato sul documentario The Loving Story di Nancy Buirski 4 SINOSSI LOVING racconta la storia di coraggio e impegno di Richard e Mildred Loving, interpretati da Joel Edgerton e Ruth Negga, coppia interrazziale che si innamora e si sposa nel 1958. -

“Tha' Sounds Like Me Arse!”: a Comparison of the Translation of Expletives in Two German Translations of Roddy Doyle's

“Tha’ Sounds Like Me Arse!”: A Comparison of the Translation of Expletives in Two German Translations of Roddy Doyle’s The Commitments Susanne Ghassempur Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dublin City University School of Applied Language and Intercultural Studies Supervisor: Prof. Jenny Williams June 2009 Declaration I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: _____________________________________ ID No.: 52158284 Date: _______________________________________ ii Acknowledgments My thanks go to everyone who has supported me during the writing of this thesis and made the last four years a dream (you know who you are!). In particular, I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Jenny Williams for her constant encouragement and expert advice, without which this thesis could not have been completed. I would also like to thank the School of Applied Language & Intercultural Studies for their generous financial support and the members of the Centre for Translation & Textual Studies for their academic advice. Many thanks also to Dr. Annette Schiller for proofreading this thesis. My special thanks go to my parents for their constant -

Read the Performance Program Here!

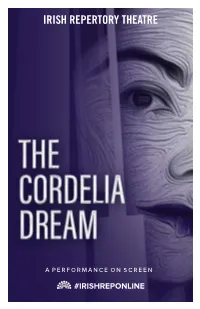

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN Irish Repertory Theatre Presents In association with Bonnie Timmermann THE CORDELIA DREAM BY MARINA CARR DIRECTED BY JOE O'BYRNE STARRING STEPHEN BRENNAN AND DANIELLE RYAN cinematography & editor set design costume design sound design & original music NICK ROBERT JESSICA DAVID RYAN BALLAGH CASHIN DOWNES production manager stage manager press representatives general manager LEO AIDAN MATT ROSS LISA MCKENNA DOHENY PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE The Present - Dublin, Ireland Running Time: 90 minutes, no intermission SPECIAL THANKS Anthony Fox, Eva Walsh, Rhona Gouldson, Archie Chen, and a very special thanks to the Howard Gilman Foundation for their support of our digital initiatives. The Cordelia Dream was first presented by the Royal Shakespeare Company at Wilton’s Music Hall on December 11, 2008. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST STEPHEN BRENNAN the Paycock (Guthrie Theatre, (Man) Stephen was a Minneapolis), Sorin in The Seagull member of the Abbey (Dublin Festival), John Bosco in The Theatre company from Chastitute (Gaiety, Dublin), The Captain 1975, playing a wide in Woyzeck in Winter (Galway Festival/ variety of roles including Barbican) and Hornby in A Kind of Joe Dowling's production Alaska (Pinter Festival, Lincoln Centre). -

September 20 19

SEPTEMBER 2019 80 YEARS OF CINEMA SEPTEMBER 2019 GLASGOWFILM.ORG | 0141 332 6535 CINEMASTERS: PEDRO ALMODÓVAR | GLASGOW YOUTH FILM FESTIVAL 12 ROSE STREET, GLASGOW, G3 6RB MRS LOWRY AND SON | TAKE ONE ACTION! | THE SOUVENIR | THE GOLDFINCH CONTENTS Access Film Club: Blinded by the Light 20 Volver 12 Contemporary Cinema Course 7 16 Ad Astra EVENT CINEMA Crossing the Line: LUX Scotland 7 presents: Under Mud Aniara 14 NT Live: A Midsummer Night’s Dream 17 The Game Changers + Q&A 5 Bait 14 NT Live Encore: One Man Two Guvnors 17 Preview: For Sama + Q&A 4 Die Tomorrow 15 GLASGOW YOUTH Preview: The Last Tree + Q&A 5 The Farewell 16 FILM FESTIVAL The Third Man - 70th Anniversary 7 For Sama 15 BAFTA Scotland presents: A Day in the 11 6 The Goldfinch 17 Director’s Life Velvet Goldmine - 35mm + Discussion Hail Satan? 15 The Biggest Little Farm + recorded Q&A 10 Vincent Price: Master of Menace, Lover 4 of Life + The Abominable Dr Phibes Hotel Mumbai 17 Closing Gala: Scott Pilgrim vs The World 11 Women's Support Project: 16 Code Geass: Lelouch of the 5 Ladyworld 9 Abused: The Untold Story The Last Tree 5 Re;Surrection 10 TAKE ONE ACTION! Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love 17 Drag Kids FILM FESTIVAL Family Gala: Fantastic Mr Fox 11 Mean Girls 6 Anbessa 13 GFF Presents: Finding Your Feet in Film 11 Memory: The Origins of Alien 14 Ghost Fleet 13 GYFF: ShortListed 9 Midnight Cowboy - 50th Anniversary 15 Midnight Traveler 13 9 Mother 16 Late Night: Heathers Preview: Sorry We Missed You 13 @glasgowfilm Opening Gala: The Farewell 9 Mrs Lowry and Son 15 Scheme Birds + Q&A 13 Phoenix + Q&A 10 Once Upon a Time..