Spiritual Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Introducing Yemoja

1 2 3 4 5 Introduction 6 7 8 Introducing Yemoja 9 10 11 12 Solimar Otero and Toyin Falola 13 14 15 16 17 18 Mother I need 19 mother I need 20 mother I need your blackness now 21 as the august earth needs rain. 22 —Audre Lorde, “From the House of Yemanjá”1 23 24 “Yemayá es Reina Universal porque es el Agua, la salada y la dul- 25 ce, la Mar, la Madre de todo lo creado / Yemayá is the Universal 26 Queen because she is Water, salty and sweet, the Sea, the Mother 27 of all creation.” 28 —Oba Olo Ocha as quoted in Lydia Cabrera’s Yemayá y Ochún.2 29 30 31 In the above quotes, poet Audre Lorde and folklorist Lydia Cabrera 32 write about Yemoja as an eternal mother whose womb, like water, makes 33 life possible. They also relate in their works the shifting and fluid nature 34 of Yemoja and the divinity in her manifestations and in the lives of her 35 devotees. This book, Yemoja: Gender, Sexuality, and Creativity in the 36 Latina/o and Afro-Atlantic Diasporas, takes these words of supplica- 37 tion and praise as an entry point into an in-depth conversation about 38 the international Yoruba water deity Yemoja. Our work brings together 39 the voices of scholars, practitioners, and artists involved with the inter- 40 sectional religious and cultural practices involving Yemoja from Africa, 41 the Caribbean, North America, and South America. Our exploration 42 of Yemoja is unique because we consciously bridge theory, art, and 43 xvii SP_OTE_INT_xvii-xxxii.indd 17 7/9/13 5:13 PM xviii Solimar Otero and Toyin Falola 1 practice to discuss orisa worship3 within communities of color living in 2 postcolonial contexts. -

Umbanda: Africana Or Esoteric? Open Library of Humanities, 6(1): 25, Pp

ARTICLE How to Cite: Engler, S 2020 Umbanda: Africana or Esoteric? Open Library of Humanities, 6(1): 25, pp. 1–36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.469 Published: 30 June 2020 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of Open Library of Humanities, which is a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Open Library of Humanities is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. Steven Engler, ‘Umbanda: Africana or Esoteric?’ (2020) 6(1): 25 Open Library of Humanities. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/olh.469 ARTICLE Umbanda: Africana or Esoteric? Steven Engler Mount Royal University, CA [email protected] Umbanda is a dynamic and varied Brazilian spirit-incorporation tradition first recorded in the early twentieth century. This article problematizes the ambiguity of categorizing Umbanda as an ‘Afro-Brazilian’ religion, given the acknowledged centrality of elements of Kardecist Spiritism. It makes a case that Umbanda is best categorized as a hybridizing Brazilian Spiritism. Though most Umbandists belong to groups with strong African influences alongside Kardecist elements, many belong to groups with few or no African elements, reflecting greater Kardecist influence. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Nja...I Am the Ancient Mother of Fishes. 1 In

Janet Langlois F'olklore Institute Indiana University 1 I am Yem?nja....I am the Ancient Mother of Fishes. In YorubaLand, her devotees honor the origa Yempnja as a source of life, of fertility, of abundance. Some Bee her in the depths of the river Ogun near the city Abeokuta, Nigeria, where they have built her principal temple in the Ibora quarter.2 Some feel her presence in the small stream near one of her Ibadan temples. Others know she comes to them from the sea when they call her to their temple in Ibadan city.3 They sing her praises in Abfokuta, Ibadan, Porto-Novo, Ketou, Adja Wbrb, and Ouidah. They know her to be powerful and her very name symbolizes this p wer: "~emoJa"fuses "yeye" which ie "mother" with "eja" which is She is the source of food and drink -- of life. When Yorubaland extended and fragmented itself in the New World, Ycmoja and her memory extended and fragmented, too. When her devotees, caught in the olave traffic and channeled through port cities on the Slave Coast of West Africa, reached ports in Brazil, Cuba, Haiti, and Trinidad; they maintained her cult as well as those of the other origa. Their descendants too are faithful to her. Yet she is not in the New World what ahe was in the old one. She has become fragmented and fused into a greater whole. She has lost and she has gained. The fragmentation of her name in the New World is indicative. She is "~emaya"in Cuba. She is "~emanjQ," "1emanj6," "~emanja,"etc. -

AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Open Educational Resources Borough of Manhattan Community College 2021 AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture Remi Alapo CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bm_oers/29 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Presented as part of the discussion on West Africa about the instructor’s Heritage in the AFN 121 course History of African Civilizations on April 20, 2021. Yoruba Tradition and Culture Prof. Remi Alapo Department of Ethnic and Race Studies Borough of Manhattan Community College [BMCC]. Questions / Comments: [email protected] AFN 121 - History of African Civilizations (Same as HIS 121) Description This course examines African "civilizations" from early antiquity to the decline of the West African Empire of Songhay. Through readings, lectures, discussions and videos, students will be introduced to the major themes and patterns that characterize the various African settlements, states, and empires of antiquity to the close of the seventeenth century. The course explores the wide range of social and cultural as well as technological and economic change in Africa, and interweaves African agricultural, social, political, cultural, technological, and economic history in relation to developments in the rest of the world, in addition to analyzing factors that influenced daily life such as the lens of ecology, food production, disease, social organization and relationships, culture and spiritual practice. -

From Maroons to Mardi Gras

FROM MAROONS TO MARDI GRAS: THE ROLE OF AFRICAN CULTURAL RETENTION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE BLACK INDIAN CULTURE OF NEW ORLEANS A MASTERS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF LIBERTY UNIVERSITY BY ROBIN LIGON-WILLIAMS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY DECEMBER 18, 2016 Copyright: Robin Ligon-Williams, © 2016 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv. ABSTRACT vi. CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 History and Background 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Research Question 2 Glossary of Terms 4 Limitations of the Study 6 Assumptions 7 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 9 New Orleans-Port of Entry for African Culture 9 Brotherhood in Congo Square: Africans & Native Americans Unite 11 Cultural Retention: Music, Language, Masking, Procession and Ritual 13 -Musical Influence on Jazz & Rhythm & Blues 15 -Language 15 -Procession 20 -Masking: My Big Chief Wears a Golden Crown 23 -African Inspired Masking 26 -Icons of Resistance: Won’t Bow Down, Don’t Know How 29 -Juan “Saint” Maló: Epic Hero of the Maroons 30 -Black Hawk: Spiritual Warrior & Protector 34 ii. -Spiritualist Church & Ritual 37 -St. Joseph’s Day 40 3. METHODOLOGY 43 THESIS: 43 Descriptions of Research Tools/Data Collection 43 Participants in the Study 43 Academic Research Timeline 44 PROJECT 47 Overview of the Project Design 47 Relationship of the Literature to the Project Design 47 Project Plan to Completion 49 Project Implementation 49 Research Methods and Tools 50 Data Collection 50 4. IN THE FIELD 52 -Egungun Masquerade: OYOTUNJI Village 52 African Cultural Retentions 54 -Ibrahima Seck: Director of Research, Whitney Plantation Museum 54 -Andrew Wiseman: Ghanaian/Ewe, Guardians Institute 59 The Elders Speak 62 -Bishop Oliver Coleman: Spiritualist Church, Greater Light Ministries 62 -Curating the Culture: Ronald Lewis, House of Dance & Feathers 66 -Herreast Harrison: Donald Harrison Sr. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Ọbè ̣Dú Festival in Ọ̀bà-Ilé in Ọ̀ṣun State, Nigeria

In Honour of a War Deity: Ọbèdụ́ Festival in Òbạ̀ -Ilé in Òṣuṇ State, Nigeria by Iyabode Deborah Akande [email protected] Department of Linguistics and African Languages Ọbáfémị Awólówọ̀ ̣University, Ilé-Ifè,̣ Nigeria Abstract This paper focuses on an account of Ọbèdú,̣ a deity in Yorùbá land that is popular and instrumental to the survival of the Òbạ̀ -Ilé people in Òṣuṇ State, Nigeria. Data for the study was drawn from interviews conducted with eight informants in Òbạ̀ -Ilé which comprised of the king, three chiefs, three Ọbèdụ́ priests, and the palace bard. Apart from the interviews, the town was visited during the annual festival of Ọbèdụ́ and where the performances were recorded. In paying attention to the history and orature of Ọbèdú,̣ it was found out that Ọbèdụ́ who was deified, was also a great herbalist, warrior and Ifá priest during his life time. It was concluded that the survival of Òbạ̀ -Ilé and the progress achieved, could be linked to the observance of the Ọbèdụ́ festival, and that a failure not continue the event would be detrimental to the community. Introduction The worldview of the Yorùbá, a race which is domiciled mainly in the Southwestern part of Nigeria, cannot be properly understood without a good knowledge of their belief about their deities and gods. In Yorùbá mythology, gods and deities are next to Olódùmarè and, as such, they are revered and worshipped (Idowu 1962). The Yorùbá believe in spirits, ancestors and unseen forces and whenever they are confronted with some problems, they often seek the support of gods and deities by offering sacrifices to them and by appeasing them. -

DIANA PATON & MAARIT FORDE, Editors

diana paton & maarit forde, editors ObeahThe Politics of Caribbean and Religion and Healing Other Powers Obeah and Other Powers The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing diana paton & maarit forde, editors duke university press durham & london 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Katy Clove Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Newcastle University, which provided funds toward the production of this book. Foreword erna brodber One afternoon when I was six and in standard 2, sitting quietly while the teacher, Mr. Grant, wrote our assignment on the blackboard, I heard a girl scream as if she were frightened. Mr. Grant must have heard it, too, for he turned as if to see whether that frightened scream had come from one of us, his charges. My classmates looked at me. Which wasn’t strange: I had a reputation for knowing the answer. They must have thought I would know about the scream. As it happened, all I could think about was how strange, just at the time when I needed it, the girl had screamed. I had been swimming through the clouds, unwillingly connected to a small party of adults who were purposefully going somewhere, a destination I sud- denly sensed meant danger for me. Naturally I didn’t want to go any further with them, but I didn’t know how to communicate this to adults and ones intent on doing me harm. -

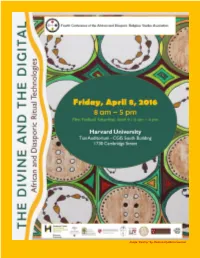

2016 Conference Program

Image “Destiny” by Deanna Oyafemi Lowman MOYO ~ BIENVENIDOS ~ E KAABO ~ AKWABAA BYENVENI ~ BEM VINDOS ~ WELCOME Welcome to the fourth conference of the African and Diasporic Religious Studies Association! ADRSA was conceived during a forum of scholars and scholar- practitioners of African and Diasporic religions held at the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School in October 2011 and the idea was solidified during the highly successful Sacred Healing and Wholeness in Africa and the Americas symposium held at Harvard in April 2012. Those present at the forum and the symposium agreed that, as with the other fields with which many of us are affiliated, the expansion of the discipline would be aided by the formation of an association that allows researchers to come together to forge relationships, share their work, and contribute to the growing body of scholarship on these rich traditions. We are proud to be the first US-based association dedicated exclusively to the study of African and Diasporic Religions and we look forward to continuing to build our network throughout the country and the world. Although there has been definite improvement, Indigenous Religions of all varieties are still sorely underrepresented in the academic realms of Religious and Theological Studies. As a scholar- practitioner of such a tradition, I am eager to see that change. As of 2005, there were at least 400 million people practicing Indigenous Religions worldwide, making them the 5th most commonly practiced class of religions. Taken alone, practitioners of African and African Diasporic religions comprise the 8th largest religious grouping in the world, with approximately 100 million practitioners, and the number continues to grow. -

On the Rationality of Traditional Akan Religion: Analyzing the Concept of God

Majeed, H. M/ Legon Journal of the Humanities 25 (2014) 127-141 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ljh.v25i1.7 On the Rationality of Traditional Akan Religion: Analyzing the Concept of God Hasskei M. Majeed Lecturer, Department of Philosophy and Classics, University of Ghana, Legon Abstract This paper is an attempt to show how logically acceptable (or rational) belief in Traditional Akan religion is. The attempt is necessitated by the tendency by some scholars to (mis) treat all religions in a generic sense; and the potential which Akan religion has to influence philosophical debates on the nature of God and the rationality of belief in God – generally, on the practice of religion. It executes this task by expounding some rational features of the religion and culture of the Akan people of Ghana. It examines, in particular, the concept of God in Akan religion. This paper is therefore a philosophical argument on the sacred and institutional representation of what humans have come to refer to as “religious.” Keywords: rationality; good; Akan religion; God; worship By “Traditional Akan religion,” I mean the indigenous system of sacred beliefs, values, and practices of the Akan people of Ghana1. This is not to say, however, that the Akans are only found in Ghana. Traditional Akan religion has features that distinguish it from other African religions, and more so from non-African ones. This seems to underscore the point that religious practice varies across the cultures of the world, although all religions could share some common attributes. Yet, some philosophers and religionists, for instance, have not been measured in their presentation of the general features of religion. -

Being Muslim: a Cultural History of Women of Chicago in the 1990S, Castor Takes the Reader on a Color in American Islam

congresses and the incorporation of Orishas into national politics, Black Power and African con- Trinidadian carnival (including the tensions it sciousness for shaping what became (and what con- caused within Ifa/Orisha communities) to highlight tinues to become) Ifa/Orisha religion as practiced differences between what Castor calls Yoruba-cen- in Trinidad. In this, we learn how specific local con- tric shrines (religious communities that look to texts, international connections and particular trav- Africa for spiritual authority and ritual guidance) elers shaped and continue to mold this diasporic and Trinidad-centric shrines (communities rooted African-based religion in Trinidad, placing Castor’s in local practices and histories in Trinidad). Chap- ethnography alongside recent work of scholars of ter 4 explores the growing transnational networks Yorub a religion in places like South Carolina of practitioners by focusing on connections (Clarke 2004) and Cuba (Beliso-De Jesus 2015). between the Caribbean and Africa, especially This highly recommended ethnography would be a through the experiences of many who traveled to very valuable text for undergraduate and graduate Nigeria for participation in the Seventh annual students, general scholars and practitioners alike. Orisha World Congress in Nigeria in 2001. Here, Castor investigates how people were initiated in REFERENCES CITED Nigeria and what she calls spiritual economies: Beliso-De Jesus, Aisha. 2015. Electric Santeria: Racial and Sexual “the transfer and exchange of value...for spiritual Assemblages of Transnational Religion, New York: Columbia labor” (p. 122). Chapter 5 explores how the first University Press. Clarke, Kamari. 2004. Mapping Yoruba Networks: Power and Ifa divinatory lineages were established in Trini- Agency in the Making of Transnational Communities.