Composting Toilets May Serve As a Solution for a Number of Issues Facing Our Society Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Incineration Medical Waste Treatment Technologies

Non-Incineration Medical Waste Treatment Technologies A Resource for Hospital Administrators, Facility Managers, Health Care Professionals, Environmental Advocates, and Community Members August 2001 Health Care Without Harm 1755 S Street, N.W. Unit 6B Washington, DC 20009 Phone: 202.234.0091 www.noharm.org Health Care Without Harm 1755 S Street, N.W. Suite 6B Washington, DC 20009 Phone: 202.234.0091 www.noharm.org Printed with soy-based inks on Rolland Evolution, a 100% processed chlorine-free paper. Non-Incineration Medical Waste Treatment Technologies A Resource for Hospital Administrators, Facility Managers, Health Care Professionals, Environmental Advocates, and Community Members August 2001 Health Care Without Harm www.noharm.org Preface THE FOUR LAWS OF ECOLOGY . Meanwhile, many hospital staff, such as Hollie Shaner, RN of Fletcher-Allen Health Care in Burlington, Ver- 1. Everything is connected to everything else, mont, were appalled by the sheer volumes of waste and 2. Everything must go somewhere, the lack of reduction and recycling efforts. These indi- viduals became champions within their facilities or 3. Nature knows best, systems to change the way that waste was being managed. 4. There is no such thing as a free lunch. Barry Commoner, The Closing Circle, 1971 In the spring of 1996, more than 600 people – most of them community activists – gathered in Baton Rouge, Up to now, there has been no single resource that pro- Louisiana to attend the Third Citizens Conference on vided a good frame of reference, objectively portrayed, of Dioxin and Other Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals. The non-incineration technologies for the treatment of health largest workshop at the conference was by far the one care wastes. -

Medical Waste Treatment Technologies

Medical Waste Treatment Technologies Ruth Stringer International Science and Policy Coordinator Health Care Without Harm Dhaka January 2011 Who is Health Care Without Harm? An International network focussing on two fundamental rights: • Right to healthcare • Right to a healthy environment Health Care Without Harm • Issues • Offices in – Medical waste –USA –Mercury – Europe – PVC – Latin America – Climate and health – South East Asia – Food • Key partners in – Green buildings –South Africa – Pharmaceuticals – India –Nurses – Tanzania – Safer materials –Mexico • Members in 53 countries Global mercury phase-out • HCWH and WHO partnering to eliminate mercury from healthcare • Part of UN Environment Programme's Mercury Products Partnership. • www.mercuryfreehealthcare.org • HCWH and WHO are principal cooperating agencies • 8-country project to reduce impacts from medical waste – esp dioxins and mercury • Model hospitals in Argentina, India, Latvia, Lebanon, the Philippines, Senegal and Vietnam • Technology development in Tanzania Incineration No longer a preferred treatment technology in many places Meeting modern emission standards costs millions of dollars Ash must be treated as hazardous waste Small incinerators are highly polluting Maintenance costs can be high, breakdowns common Decline in Medical Waste Incinerators in the U.S. 8,000 6,200 6,000 5,000 4,000 2,400 2,000 Incinerators 115 83 57 #of Medical Waste Waste Medical #of 0 1988 1994 1997 2003 2006 2008 Year SOURCES: 1988: “Hospital Waste Combustion Study-Data Gathering Phase,” USEPA, December 1998; 1994: “Medical Waste Incinerators-Background Information for Proposed Standards and Guidelines: Industry Profile Report for New and Existing Facilities,” USEPA, July 1994; 1997: 40 CFR 60 in the Federal Register, Vol. -

Waste Technologies: Waste to Energy Facilities

WASTE TECHNOLOGIES: WASTE TO ENERGY FACILITIES A Report for the Strategic Waste Infrastructure Planning (SWIP) Working Group Complied by WSP Environmental Ltd for the Government of Western Australia, Department of Environment and Conservation May 2013 Quality Management Issue/revision Issue 1 Revision 1 Revision 2 Revision 3 Remarks Date May 2013 Prepared by Kevin Whiting, Steven Wood and Mick Fanning Signature Checked by Matthew Venn Signature Authorised by Kevin Whiting Signature Project number 00038022 Report number File reference Project number: 00038022 Dated: May 2013 2 Revised: Waste Technologies: Waste to Energy Facilities A Report for the Strategic Waste Infrastructure Planning (SWIP) Working Group, commissioned by the Government of Western Australia, Department of Environment and Conservation. May 2013 Client Waste Management Branch Department of Environment and Conservation Level 4 The Atrium, 168 St George’s Terrace, PERTH, WA 6000 Locked Bag 104 Bentley DC WA 6983 Consultants Kevin Whiting Head of Energy-from-Waste & Biomass Tel: +44 207 7314 4647 [email protected] Mick Fanning Associate Consultant Tel: +44 207 7314 5883 [email protected] Steven Wood Principal Consultant Tel: +44 121 3524768 [email protected] Registered Address WSP Environmental Limited 01152332 WSP House, 70 Chancery Lane, London, WC2A 1AF 3 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................. 6 1.1 Objectives ................................................................................ -

Designing an Evaluation Protocol for Composting Toilet Systems ______

Designing an Evaluation Protocol for Composting Toilet Systems ______________________________________________________________ An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science. By: Camryn Berry Zahava Preil Lena Sophia Thompson Date: February 26, 2020 Report Submitted to: Professor Seth Tuler and Professor Isa Bar-On This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects Abstract Two billion people worldwide lack access to adequate sanitation which ensures hygienic separation of human excreta from human contact. Composting toilets help address this health hazard by containing waste and reducing risk of disease. The goal of our project was to develop a cost-effective, user-friendly and minimally-disruptive protocol to evaluate the function, use and maintenance of composting toilets. This protocol was trialed at Kibbutz Lotan in Israel. We concluded that Lotan’s system was effective, though inefficient. The trial allowed us to identify potential improvements to the protocol that can be applied in the future. Our protocol is successful for evaluating the success of a system and how adequately it can address the unnecessary loss of life caused by inadequate sanitation. ii Acknowledgements We would like to thank the people who helped make our project possible. Firstly, we would like to thank our sponsor Alex Cicelsky of the Kibbutz Lotan Center for Creative Ecology. -

Workplace Recycling

SETTING UP Workplace Recycling 1 Form a Enlist a group of employees interested in recycling and waste prevention to set up and monitor collection systems Recycling Team to ensure ongoing success. This is a great team-building exercise and can positively impact employee morale as well as the environment. 2 Determine Customize your recycling program based on your business. Consider performing a waste audit or take inventory of materials the kinds of materials in your trash & recycling. to recycle Commonly recycled business items: Single-Stream Recycling • Aluminum & tin cans; plastic & glass bottles • Office paper, newspaper, cardboard • Magazines, catalogs, file folders, shredded paper 3 Contact Find out if recycling services are already in place. If not, ask the facility or property manager to set them up. Point your facility out that in today’s environment, employees expect to recycle at work and that recycling can potentially reduce costs. If recycling is currently provided, check with the manager to make sure good recycling education materials or property are available to all employees. This will help employees to recycle right, improve the quality of recyclable materials, manager and increase recycling participation. 4 Coordinate Work station recycling containers – Provide durable work station recycling containers or re-use existing training containers like copy paper boxes. Make recycling available at each work station. with the Click: Get-Started-Recycling-w_glass or Get-Started-Recycling-without-glass to print recycling container labels. Label your trash containers as well: Get-Started-Trash-with-food waste or janitorial crew Get-Started-Trash -no-food waste. and/or staff Central area containers – Evaluate the type and size of containers for common areas like conference rooms, hallways, reception areas, and cafes, based on volume, location, and usage. -

Sector N: Scrap and Waste Recycling

Industrial Stormwater Fact Sheet Series Sector N: Scrap Recycling and Waste Recycling Facilities U.S. EPA Office of Water EPA-833-F-06-029 February 2021 What is the NPDES stormwater program for industrial activity? Activities, such as material handling and storage, equipment maintenance and cleaning, industrial processing or other operations that occur at industrial facilities are often exposed to stormwater. The runoff from these areas may discharge pollutants directly into nearby waterbodies or indirectly via storm sewer systems, thereby degrading water quality. In 1990, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) developed permitting regulations under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) to control stormwater discharges associated with eleven categories of industrial activity. As a result, NPDES permitting authorities, which may be either EPA or a state environmental agency, issue stormwater permits to control runoff from these industrial facilities. What types of industrial facilities are required to obtain permit coverage? This fact sheet specifically discusses stormwater discharges various industries including scrap recycling and waste recycling facilities as defined by Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) Major Group Code 50 (5093). Facilities and products in this group fall under the following categories, all of which require coverage under an industrial stormwater permit: ◆ Scrap and waste recycling facilities (non-source separated, non-liquid recyclable materials) engaged in processing, reclaiming, and wholesale distribution of scrap and waste materials such as ferrous and nonferrous metals, paper, plastic, cardboard, glass, and animal hides. ◆ Waste recycling facilities (liquid recyclable materials) engaged in reclaiming and recycling liquid wastes such as used oil, antifreeze, mineral spirits, and industrial solvents. -

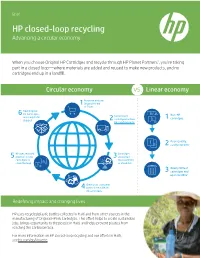

HP Closed-Loop Recycling Advancing a Circular Economy

• Brief HP closed-loop recycling Advancing a circular economy When you choose Original HP Cartridges and recycle through HP Planet Partners1, you’re taking part in a closed loop—where materials are added and reused to make new products, and no cartridges end up in a landfill. Circular economy vs. Linear economy Purchase and use 1 Original HP Ink or Toner New Original HP Cartridges 6 Return used Non-HP are ready to be 1 cartridges shipped 2 cartridges for free hp.com/hprecycle Poor-quality, 2 costly reprints2 HP uses recycled Cartridges 5 plastics3 in new 3 are sorted, cartridges to disassembled, close the loop or shredded Nearly 90% of 3 cartridges end up in landfills4 Other post-consumer 4 plastics are added to ink cartridges Redefining impact and changing lives HP uses recycled plastic bottles collected in Haiti and from other sources in the manufacturing of Original HP Ink Cartridges. This effort helps to create sustainable jobs, brings opportunity to the people in Haiti, and helps prevent plastics from reaching the Caribbean Sea. For more information on HP closed-loop recycling and our efforts in Haiti, see hp.com/go/Rosette. Together, we’re recycling for a better world The results speak for themselves. Here’s the difference HP made in 2018 by using recycled plastic in ink cartridges instead of new plastic: 60% reduction 39% less 30% average in fossil fuel water used5 carbon footprint consumption5 Enough to supply reduction5 Conserved more than 7.9 million Americans Like taking 533 cars off 7 6 for one day 8 705 barrels of oil the road for one year Bringing used products back to life With your help, we’re closing the loop. -

Annual Report 2010

Action Earth ACRES Adeline Lo Thank You Ai Xin Society for your invaluable support Anderson Junior College Andrew Tay Assembly of Youth for the Environment So many individuals, food outlets AWARE Balakrishnan Matchap and organizations gave their Betty Hoe invaluable effort, time and Bishan Community Library resources to light the path Bright Hill Temple British Petroleum (BP) towards vegetarianism. Space Bukit Merah Public Library may not have allowed us to list Cat Welfare Society Catherina Hosoi everyone, but all the same, we Central Library of the National Library Board extend our most heartfelt thanks Chong Hua Tong Tou Teck Hwee movement to you. Douglas Teo Dr Raymond Yuen Environmental Challenge Organisation Vegetarian Society (Singapore) ROS Registration No.: ROS/RCB 0123/1999 Singapore 3 Pemimpin Drive, #07-02, Lip Hing Bldg, Charity Registration No.: 1851 UEN: S99SS0065J Family Service Centre (Yishun) Singapore 576147 Foreign Domestic Worker Association (address for correspondence only) Gelin www.vegetarian-society.org Genesis Vegetarian Health Food Restaurant [email protected] Global Indian International School Green Kampung website Greendale Secondary School Green Roundtable Noah’s Ark Natural Animal Sanctuary Guangyang Primary School NUS SAVE GUI (Ground Up Initiative) NutriHub Herty Chen Post Museum Indonesia Vegetarian Society Queensway Secondary School International Vegetarian Union Prof Harvey Neo Juggi Ramakrishnan Raffles Institution Lim Yi Ting Rameshon Murugiah Kevin Tan Rosina Arquati Heng Guan Hou Serene Peh Hort Park Singapore Buddhist Federation Kampung Senang Charity and Education Singapore Kite Association Foundation Singapore Malayalee Association Loving Hut Restaurants Singapore Polytechnic Singapore Sports Council Mahaya Menon Singapore Tourism Board Maria and Ana Laura Rivarola Singapore Vegetarian Meetup Groups ANNUALREPORTFOR2010 Mayura Mohta SPCA Maitreyawira School St Anthony’s Canossian Secondary School Media Corp Straits Times MEVEG (Middle East Vegetarian Group) T. -

Waste Treatment Solutions

Waste Treatment Solutions Waste Treatment Solutions As industry leaders, we offer customers across North America reliable, safe and compliant solutions for over 600 hazardous waste streams, PCBs, TSCA and non-hazardous waste. Unequaled service. Solutions you can trust. USecology.com To support the needs of customers from coast to coast, US Ecology has 19 treatment and recycling facilities throughout North America, including some of the largest treatment and stabilization operations. This enables us to accept waste in a wide range of consistencies and shipping containers, from bulk liquids and solids to drums, totes and bags. Plus, our facilities are backed by six state-of-the-art hazardous and radioactive waste landfills, along with a nationwide transportation network. Treatment Processes US Ecology’s RCRA-permitted and TSCA-approved facilities US Ecology is the only commercial offer a wide variety of waste treatment technologies. treatment company in the USA • Chemical oxidation processes to treat waste that is USEPA-authorized to delist containing organic contaminants 15 inorganic hazardous wastes. • Microencapsulation to reduce the leachability Delisting offers an attractive, safe of hazardous debris streams, allowing material to be safely disposed in RCRA Subtitle C landfills and more compliant disposal • Chemical stabilization de-characterizes waste, option, particularly for those with enabling safe landfill disposal F-listed hazardous waste codes. • Thermal desorption to process and/or recycle high organic contaminated materials For more information: • Regenerative Thermal Oxidation (RTO) air Call (800) 592-5489 or management system enables management go to www.usecology.com of high-VOC, RCRA-regulated wastes • Wastewater treatment for hazardous and non-hazardous wastewater, including oily and corrosive streams • Cyanide destruction and oxidizer deactivation treatment technologies. -

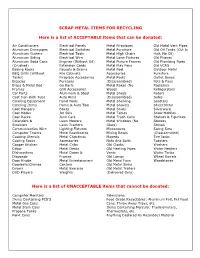

SCRAP METAL ITEMS for RECYCLING Here Is a List Of

SCRAP METAL ITEMS FOR RECYCLING Here is a list of ACCEPTABLE items that can be donated: Air Conditioners Electrical Panels Metal Fireplaces Old Metal Vent Pipes Aluminum Drainpipes Electrical Switches Metal Furniture Old Oil Tanks (Cut In Aluminum Gutters Electrical Tools Metal High Chairs Half, No Oil) Aluminum Siding Electrical Wire Metal Lawn Fixtures Old Phones Aluminum Soda Cans Engines (Without Oil) Metal Picture Frames Old Plumbing Pipes (Crushed) Extension Cords Metal Play Pens Old VCRS Baking Racks Faucets & Drains Metal Pool Outdoor Metal BBQ Grills (Without File Cabinets Accessories Furniture Tanks) Fireplace Accessories Metal Pools Outlet Boxes Bicycles Furnaces (Disassembled) Pots & Pans Brass & Metal Bed Go Karts Metal Rakes (No Radiators Frames Grill Accessories Wood) Refrigerators Car Parts Aluminum & Steel Metal Sheds Rotors Cast Iron Bath Tubs Auto Rims (Disassembled) Safes Catering Equipment Hand Tools Metal Shelving Scooters Catering Items Home & Auto Tool Metal Shovels Sheet Metal Coat Hangers Boxes Metal Studs Silverware Coat Hooks Jet Skis Metal Tables Snow Mobiles Coat Racks Junk Cars Metal Trash Cans Statues & Figurines Colanders & Lawn Mowers Metal Windows (No Stereos Strainers Lawn Tractors Glass) Stoves Communication Wire Lighting Fixtures Microwaves Swing Sets Computer Towers Metal Baseboards Mixing Bowls (Disassembled) Cooking Utensils Metal Christmas Mopeds Tire Jacks Cooling Racks Accessories Nuts And Bolts Toasters Copper Kitchen Metal Cribs Old Clocks Washers Décor Metal Desks Old Heating Pipes Water Heaters Dishwashers Metal Doors & Vents Water Tanks Disposals Frames Old Lamps Wheel Barrels Door Knobs Metal Entertainment Old Metal Fans Woodstoves Doorbells/Chimes Centers Old Metal Sinks Dryers Metal Exercise Old Metal Trailers DVD Players Weights (Delivered Only) Here is a list of UNACCEPTABLE items that cannot be donated: Computer Monitors Televisions Items Containing PCB’S Food Grade Recyclables: Aluminum Foil, Pet Food Metal Gas Cans Cans, Throw Away Trays, etc. -

Waste Management

10 Waste Management Coordinating Lead Authors: Jean Bogner (USA) Lead Authors: Mohammed Abdelrafie Ahmed (Sudan), Cristobal Diaz (Cuba), Andre Faaij (The Netherlands), Qingxian Gao (China), Seiji Hashimoto (Japan), Katarina Mareckova (Slovakia), Riitta Pipatti (Finland), Tianzhu Zhang (China) Contributing Authors: Luis Diaz (USA), Peter Kjeldsen (Denmark), Suvi Monni (Finland) Review Editors: Robert Gregory (UK), R.T.M. Sutamihardja (Indonesia) This chapter should be cited as: Bogner, J., M. Abdelrafie Ahmed, C. Diaz, A. Faaij, Q. Gao, S. Hashimoto, K. Mareckova, R. Pipatti, T. Zhang, Waste Management, In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Waste Management Chapter 10 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................. 587 10.5 Policies and measures: waste management and climate ....................................................... 607 10.1 Introduction .................................................... 588 10.5.1 Reducing landfill CH4 emissions .......................607 10.2 Status of the waste management sector ..... 591 10.5.2 Incineration and other thermal processes for waste-to-energy ...............................................608 10.2.1 Waste generation ............................................591 10.5.3 Waste minimization, re-use and -

Utilization of Waste Cooking Oil Via Recycling As Biofuel for Diesel Engines

recycling Article Utilization of Waste Cooking Oil via Recycling as Biofuel for Diesel Engines Hoi Nguyen Xa 1, Thanh Nguyen Viet 2, Khanh Nguyen Duc 2 and Vinh Nguyen Duy 3,* 1 University of Fire Fighting and Prevention, Hanoi 100000, Vietnam; [email protected] 2 School of Transportation and Engineering, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, Hanoi 100000, Vietnam; [email protected] (T.N.V.); [email protected] (K.N.D.) 3 Faculty of Vehicle and Energy Engineering, Phenikaa University, Hanoi 100000, Vietnam * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 March 2020; Accepted: 2 June 2020; Published: 8 June 2020 Abstract: In this study, waste cooking oil (WCO) was used to successfully manufacture catalyst cracking biodiesel in the laboratory. This study aims to evaluate and compare the influence of waste cooking oil synthetic diesel (WCOSD) with that of commercial diesel (CD) fuel on an engine’s operating characteristics. The second goal of this study is to compare the engine performance and temperature characteristics of cooling water and lubricant oil under various engine operating conditions of a test engine fueled by waste cooking oil and CD. The results indicated that the engine torque of the engine running with WCOSD dropped from 1.9 Nm to 5.4 Nm at all speeds, and its brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) dropped at almost every speed. Thus, the thermal brake efficiency (BTE) of the engine fueled by WCOSD was higher at all engine speeds. Also, the engine torque of the WCOSD-fueled engine was lower than the engine torque of the CD-fueled engine at all engine speeds.