On the Connection Between the Monasteries of Kent in the Saxon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quebec House Lorraine Sencicle

QUEBEC HOUSE LORRAINE SENCICLE ot far from Chartwell Edward Wolfe rented Nis Quebec House, the until 1738, was originally childhood home of Sir built betw een 1530 and General James Wolfe 1550. The first building (1727-1759) and now was an L-shaped timber owned by the National framed house but it was Trust. I was particularly altered in the 1630's to a interested in this part of ‘double pile' house, our trip for my interest in popular at that time. In General James Wolfe the 18th century the front stemmed from when I wall of the house was was preparing the case replaced with a parapet against a proposed fagade but by the 1880s development on Western the house was divided in Heights back in the late two. One part became 1980's, early 1990's. The Quebec House West and main thrust of my was used as a school. James Wolfe argument was about the Courtesy of the National Trust historic fortifications and The National Trust has I drew parallels with those in Quebec, recreated Quebec House in the Georgian Canada. The latter are located within a style, so that the rooms display furniture World Heritage Site, a designation given and artefacts that belonged to the Wolfe in 1985. In English history, Jam es Wolfe family. One room held particular is synonymous with Quebec and I had fascination for both Alan, my husband, every reason to believe that the General and myself, as it was a depository of was in Dover prior to the Quebec papers, pictures and maps appertaining campaign - the trip to Westerham to the events that led up to the historic confirmed this. -

Restoration of Dover Castle, the Main Room

Restoration of Dover Castle, the main room THE DOVER SOCIETY FOUNDED IN 1988 Registered with the Civic Trust, Affiliated to the Kent Federation of Amenity Societies Registered Charity No. 299954 PRESIDENT Brigadier Maurice Atherton CBE VICE-PRESIDENTS Miss Lillian Kay, Mrs Joan Liggett Peter Marsh, Jonathan Sloggett, Tferry Sutton, Miss Christine Waterman, Jack Woolford THE COMMITTEE Chairman Derek Leach OBE, 24 Riverdale, River, Dover CT17 OGX Tfel: 01304 823926 Email: [email protected] Vice-Chairman Jeremy Cope, 53 Park Avenue, Dover CT16 1HD Tel: 01304 211348 Email: [email protected] Hon. Secretary William Naylor, "Wood End", 87 Leyburne Rd, Dover CT16 1SH Tfel: 01304 211276 Email: [email protected] Hon. Treasurer Mike Weston, 71 Castle Avenue, Dover CT16 1EZ Tfel: 01304 202059 Email: [email protected] Membership Secretary Sheila Cope, 53 Park Avenue, Dover CT16 1HD Tfel: 01304 211348 Social Secretaries Patricia Hooper-Sherratt, Castle Lea, T&swell St, Dover CT16 1SG Tfel: 01304 228129 Email: [email protected] Georgette Rapley, 29 Queen's Gardens, Dover CT17 9AH Tfel: 01304 204514 Email: [email protected] Editor Alan Lee, 8 Cherry Tree Avenue, Dover CT16 2NL Tfel: 01304 213668 Email: [email protected] Press Secretary Tferry Sutton MBE, 17 Bewsbury Cross Lane, Whitfield, Dover CT16 3HB Tfel: 01304 820122 Email: [email protected] Planning Chairman Jack Woolford, 1066 Green Lane, Tfemple Ewell, Dover CT16 3AR Tfel: 01304 330381 Email: [email protected] Committee -

Castleguard Service of Dover Castle

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 49 1937 CASTLEGUARD SERVICE OF DOVER CASTLE. BY F. W. HARDMAN, LL.D., F.S.A. THE standard historians of Kent all narrate the early history of the office of Constable of Dover Castle and there is remark- able unanimity in their story. According to them the Conqueror, after the forfeiture and imprisonment of Bishop Odo, made a new arrangement for the ward of Dover Castle. He appointed a kinsman of his own, one John de Fiennes, to be hereditary constable and endowed him with numerous knights' fees to bear the charge of his office. John de Fiennes retained fifty-six of these fees in his own hands, but associated with himself eight other knights and bestowed on them 171 fees. This arrangement continued for some time and John de Fiennes was succeeded by his son James de Fiennes and by his grandson John de Fiennes. It was disturbed in the troubled days of Stephen but again restored and continued in the persons of Allen de Fiennes and James de Fiennes. Such in outline is the story told by Lambarde (1570, p. 157), Darell, chaplain to Queen Elizabeth (1797, p. 19), Philipott (1659, pp. 12, 16), Kilburne (1659, p. 79), Somner, Roman Ports and Forts (1693, p. 118), Harris (1719, pp. 372, 484), Jeake, Charters of the Cinque Ports (1728, p. 47), Hasted (1799, IV, 60) and Lyon, History of Dover (1814, II, 87, 192). It has been copied from these authorities by countless other writers of smaller note and is generally believed to-day. And yet the story is completely untrue. -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath. -

55.1 2 Sancho.Indd

ISSN 1514-9927 (impresa) / ISSN 1853-1555 (en línea) Anales de Historia Antigua, Medieval y Moderna 55.1 (2021) (24-37) 24 doi.org/10.34096/ahamm.v55.1.8359 El fi n de la Britania romana. Breves consideraciones sobre la inteligencia militar a partir de dos pasajes de Amiano Marcelino y Vegecio " Miguel Pablo Sancho Gómez Universidad Católica de Murcia. Campus de los Jerónimos, s/n. Guadalupe (Murcia), 30107, España. [email protected] Recibido: 27/07/2020. Aceptado: 25/08/2020 Resumen Este trabajo se enmarca en las nuevas investigaciones en torno al fi n de la Britania romana y pretende aportar algunas consideraciones de carácter militar centradas en la vigilancia, inteligencia y exploración, elementos de vital importancia a la hora de conocer los planes de cualquier enemigo. El Imperio romano contó durante muchos años con estrategias y herramientas adecuadas para tales cometidos, como explorado- res, espías y una fl ota especial, pero su abandono propició un empeoramiento de las condiciones de seguridad que llevaron fi nalmente a la pérdida del control sobre la isla. Palabras clave: Vegecio, Amiano Marcelino, ejército romano, Britania, inteligencia militar. The end of Roman Britain. Brief considerations on military intelli- gence from two fragments by Ammianus Marcellinus and Vegetius Abstract This work is inspired by the new investigations on the end of Roman Britain with the aim to refl ect on a number of military tactics such as surveillance strategies, intelligence, and exploration, elements of vital importance to know the plans of any enemy. The Roman Empire carried out for a long time adequate strategies and coun- ted on valuable resources for such tasks, as scouts, spies and a special fl eet. -

Rimska Fortifikacijska Arhitektura

Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Diplomski studij: Filozofija – povijest Josip Paulić Rimska fortifikacijska arhitektura Diplomski rad Mentorica: doc. dr. sc. Jasna Šimić Osijek, 2012. 1. Sažetak Najvažniji i temeljni element rimske fortifikacijske arhitekture svakako je vojni grad – castrum. Rimljani su bili narod vojnika, kolonizatora i osvjača, pa je rimski građanin u vojnoj obavezi bio veći dio svog života. Iz tih razloga ustroj i izgled vojnog logora pokazuje toliko zajedničkih elemenata s civilnim naseljima. Zidine grada Rima predstavljaju najreprezentativniji primjer gradske fortifikacijske arhitekture u cijelom Carstvu. Murus Servii Tulii (Servijev zid) sagrađen je u ranom 4. st. pr. n. e., a učinkovito je štitio grad do druge polovine 3. st. kad je izgrađen Murus Aurelianus (271.– 275.), zid opsega 19 km koji ipak nije spasio Rim od Alarikove pljačke i razaranja (410.), kao i one kasnije vandalske (455.). U vrijeme Republike rimski castrum (prema Polibiju) ima pravilan pravokutni, gotovo kvadratan oblik; limitiran je i orijentiran na isti način kao i grad te je omeđen jarkom i zidom. Na svakoj strani logora nalaze se jedna vrata. Istočna vrata Porta praetoria i zapadna Porta decumana povezana su decumanom (via praetoria), dok su sjeverna Porta principalis sinistra i južna vrata Porta principalis dextra spojena s via principalis (cardo). Orijentacija glavnih ulica ovisila je o položaju i usmjerenosti logora. Na križanju glavnih osi logora nalazio se praetorium – središte vojne uprave. U vojnom logoru ulica cardo (via principalis) ima veće značenje od decumana. Neki autori smatraju kako osnovne zametke rimskog urbs quadratisa treba tražiti upravo u vojnom logoru. Vojni grad – castrum - slijedi etruščansko iskustvo i kristalizira nekoliko značajnih ideja i praktičnih postavki iz političke i vojne sfere. -

Plans of Dover Castle

DOVER CASTLE DOVER CASTLE KEEP Spur Medieval tunnels Pillbox Gallery Redan St John’s Tower Horseshoe Bastion Norfolk Towers Fitzwilliam Gate Hudson’s Bastion Avranches Tower King’s barbican Arthur’s Hall Crevecoeur Tower Bell Battery Avranches Lower Flank Pencester Tower Godsfoe Tower Inner King’s bailey Second floor Gate Treasurer’s Tower East Arrow Bastion Great King’s hall Constable’s Gate tower Anti-aircraft gun emplacements Well Palace Middle bailey Four Gun Battery Site of 12th- Gate century door Cistern East Demi-Bastion King’s chamber Peverell’s Gate Church of St Mary in Castro Drawbridge Well house pit Queen Mary’s Tower Colton’s Chapel of Thomas Becket Gate Roman pharos First floor Latrine shafts Gatton’s Tower Officers’ New Barracks Lower hall Constable’s Bastion Say’s Tower Lower chamber Well Naval radar station Hurst’s Tower Site of garrison hospital Meat store Drawbridge Annexe level tunnels pit Cinque Ports prison Forebuilding stairs Lower Roman chapel Fulbert of Dover’s Tower Admiralty Look-out Ground floor c. AD1000 1181–1216 Regimental 13th century Royal Garrison Artillery Barracks Institute Hospital Battery (remains) Storeroom, later 15th century powder magazine 16th century Gunpowder magazine 18th century Rokesley’s Tower Statue of Admiral Ramsay Bread oven 19th century Canon’s Gate 20th century and later Main storeroom Drawbridge Casemate level tunnels pit Course of 13th-century curtain wall Shot Yard Battery Storeroom, N Lighter tone indicates buried later cistern 16th-century battery or underground structures Forebuilding entrance Storeroom N Shoulder of Mutton Battery 0 15 metres 0 100 metres This drawing is English Heritage copyright and is supplied for the purposes of private research. -

Dover Castle OCR Spec B

OCR HISTORY AROUND US Site Proposal Form Example from English Heritage THE CRITERIA The study of the selected site must focus on the relationship between the site, other historical sources and the aspects listed in a) to n) below. It is therefore essential that centres choose a site that allows learners to use its physical features, together with other historical sources as appropriate, to understand all of the following: a) The reasons for the location of the site within its surroundings b) When and why people first created the site c) The ways in which the site has changed over time d) How the site has been used throughout its history e) The diversity of activities and people associated with the site f) The reasons for changes to the site and to the way it was used g) Significant times in the site’s past: peak activity, major developments, turning points h) The significance of specific features in the physical remains at the site i) The importance of the whole site either locally or nationally, as appropriate j) The typicality of the site based on a comparison with other similar sites k) What the site reveals about everyday life, attitudes and values in particular periods of history l) How the physical remains may prompt questions about the past and how historians frame these as valid historical enquiries m) How the physical remains can inform artistic reconstructions and other interpretations of the site n) The challenges and benefits of studying the historic environment 1 Copyright © OCR 2018 SITE NAME: Dover Castle CREATED BY: English Heritage Learning Team Please provide an explanation of how your site meets each of the following points and include the most appropriate visual images of your site. -

THE DOVER SOCIETY FOUNDED in 1988 Registered with the Civic Trust, Affiliated to the Kent Federation of Amenity Societies Registered Charity No

A N ew sletter No. 43 April 2002 Old view of the Maison Dieu THE DOVER SOCIETY FOUNDED IN 1988 Registered with the Civic trust, Affiliated to the Kent Federation of Amenity Societies Registered Charity No. 299954 PRESIDENT Brigadier Maurice Atherton CBE VICE-PRESIDENTS: Howard Blackett, Ivan Green, Peter Johnson, Miss Lillian Kay, Peter Marsh, The Rt. Hon. The Lord Rees, Jo n ath an Sloggett, Tferry Sutton, Miss Christine Waterman, Jack Woolford and Martin Wright THE COMMITTEE C h a ir m a n & Press Secretary: Tferry Sutton MBE 17 Bewsbury Cross Lane, Whitfield, Dover CT16 3HB Tfel: 01304 820122 Vice-Chairman: Derek Leach OBE 24 Riverdale, River, Dover CT17 OGX Tfel: 01304 823926 Hon. S e c r e t a r y : William Naylor “Wood End”, 87 Leyburne Road, Dover CT16 1SH Tfel: 01304 211276 H o n . T r e a s u r e r : Mike Weston 71 Castle Avenue, Dover CT16 1EZ Tfel: 01304 202059 M e m b e r s h ip S e c r e t a r y : Sheila Cope 53 Park Avenue, Dover CT16 1HD Tfel: 01304 211348 S o c ia l S e c r e t a r y : Joan Liggett 19 Castle Avenue, Dover CT16 1HA Tfel: 01304 214886 E d it o r : Merril Lilley 5 East Cliff, Dover CT16 1LX Tfel: 01304 205254 C h a ir m a n o f P l a n n in g S u b -C o m m it t e e : Jack Woolford 1066 Green Lane, Ifemple Ewell, Dover CT16 3AR Tfel: 01304 330381 C o w g a te P r o j e c t C o -o r d in a t o r : Hugh Gordon 59 Castle Avenue, Dover CT16 1EZ Tfel: 01304 205115 A r c h iv is t : Dr S.S.G. -

Roman Britain Pdf, Epub, Ebook

100 FACTS - ROMAN BRITAIN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Miles Kelly | 48 pages | 01 Jan 2008 | Miles Kelly Publishing Ltd | 9781842369616 | English | Essex, United Kingdom 100 Facts - Roman Britain PDF Book Along with these things, we try to use a Roman style of colour. Emperor Hadrian visited in One way you sometimes become aware of the Roman mark on Britain is by driving on long, straight roads. The Fact Site requires you to enable Javascript to browse our website. Resistance to Roman rule continued in what is now Wales, particularly inspired by the Druids , the priests of the native Celtic peoples. And remember, there is no order in which to view the pages, just click on a topic in the menus and the relevant subjects are revealed. For example, the often flooded Somerset levels was like a huge market garden that provided supplies for the garrisons at Exeter , Gloucester , Bath and the forts in between. It was designed to house a large garrison of troops and presents a fascinating insight into Roman military life. Get directions. The highest, still-standing Roman building in Britain, incidentally, is the shell of a lighthouse at Dover Castle. Roman technology made its impact in road building and the construction of villas , forts and cities. A: Comparatively little. They would certainly be aware that the economy was suffering from the civil war; they would see names and faces changing on coins, but they would have no real idea. It was already closely connected with Gaul, and, when Roman civilization and its products invaded Gallia Belgica , they passed on easily to Britain. -

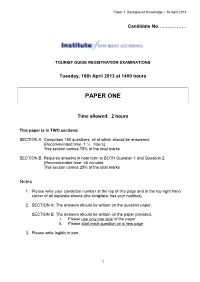

Candidate No………………

Paper 1 Background Knowledge – 16 April 2013 Candidate No……………… TOURIST GUIDE REGISTRATION EXAMINATIONS Tuesday, 16th April 2013 at 1400 hours PAPER ONE Time allowed: 2 hours This paper is in TWO sections: SECTION A Comprises 150 questions, all of which should be answered. (Recommended time: 1 ¼ hours) This section carries 75% of the total marks SECTION B Requires answers in note form to BOTH Question 1 and Question 2. (Recommended time: 45 minutes This section carries 25% of the total marks Notes 1. Please write your candidate number at the top of this page and at the top right hand corner of all separate sheets (the invigilator has your number). 2. SECTION A: The answers should be written on the question paper. SECTION B: The answers should be written on the paper provided. i. Please use only one side of the paper ii. Please start each question on a new page 3. Please write legibly in pen. 1 Paper 1 Background Knowledge -16 April 2013 SECTION A (75%) Which of Jane Austen’s novels was first published in 1813? 1. What 2nd century construction in Britain marked the north western frontier of the 2. Roman Empire? Mark Featherstone-Witty and which well- known Liverpool musician 3. co-founded the ‘Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts’? Name the British rider who won the Tour de France in 2012. 4. Which was the only part of the British Isles to be occupied by German forces 5. during the Second World War? What name is given to the confederation of ports in South East England which 6. -

Tour Brochure

Reserve your trip to England today! ULTIMATE FLEXIBILITY-The AHI Travel Passenger Protection Plan offers an Any Reason Cancellation feature. Don't worry! PROGRAM DATES INCLUDED FEATURES Travel happy! Trip #:9-23598W NOT INCLUDED-Fees for passports and, if applicable, visas, entry/departure fees; personal gratuities; laundry and dry clean- Air Program dates: July 12-22, 2018 Send to: England Castles, Cottages & Countryside ing; excursions, wines, liquors, mineral waters and meals not mentioned in this brochure under included features; travel ACCOMMODATIONS YOUR ONE-OF-A-KIND JOURNEY Arizona State University Alumni Association Land Program dates: July 13-22, 2018 Paid insurance; all items of a strictly personal nature. (With baggage handling.) c/o AHI Travel MOBILITY AND FITNESS TO TRAVEL-The right is retained to • Expert-led Enrichment programs enhance AHI Travel SMALL GROUP International Tower-Suite 600 decline to accept or to retain any person as a member of this Postage U.S. trip who, in the opinion of AHI Travel is unfit for travel or whose • Three nights in Canterbury, England, at the your insight into the region. Std. Presorted 8550 W. Bryn Mawr Avenue MAXIMUM OF physical or mental condition may constitute a danger to them- first-class ABode Canterbury. Chicago, IL 60631 selves or to others on the trip, subject only to the requirement • Discovery excursions highlight the local that the portion of the total amount paid which corresponds to 28 TRAVELERS Please contact AHI Travel at 800-323-7373 with questions regarding this trip or to the unused services and accommodations be refunded. LAND PROGRAM • Four nights in Woodstock at the first-class culture, heritage and history: Dear ASU Alumni and Friends, make a reservation.