Gilbertus Anglicus, Medicine, of the Thirteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connections Between Institutional and Lay Natural Philosophical Texts in Medieval England

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 Bridging Discourse: Connections Between Institutional and Lay Natural Philosophical Texts in Medieval England Alayne Lorden University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lorden, Alayne, "Bridging Discourse: Connections Between Institutional and Lay Natural Philosophical Texts in Medieval England" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 691. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/691 BRIDGING DISCOURSE: CONNECTIONS BETWEEN INSTITUTIONAL AND LAY NATURAL PHILOSOPHICAL TEXTS IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND by ALAYNE ELIZABETH BENSON B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2015 © 2015 Alayne E. Benson ii ABSTRACT Translations of works containing Arabic and ancient Greek knowledge of the philosophical and mechanical underpinnings of the natural world—a field of study called natural philosophy—were disseminated throughout twelfth-century England. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, institutional (ecclesiastical/university) scholars received and further developed this natural philosophical knowledge by reconciling it with Christian authoritative sources (the Bible and works by the Church Fathers). -

THE SUMMONER's OCCUPATIONAL DISEASE by THOMAS J

THE SUMMONER'S OCCUPATIONAL DISEASE by THOMAS J. GARBATY THE pilgrims which Geoffrey Chaucer described in his Prologue to the Canterbuty Tales (c. 1387) included all social ranks and vocations. Many of the tightly drawn portraits of these travellers were treated satirically, pointing up the evils of the time. The religious figures especially, the Prioress, Monk, Friar and Pardoner, all ofwhom were guilty ofsome kind ofclerical abuse, came in for severe comment. But, undoubtedly, the most vcious sketch of all is that of the Summoner, an officer ofthe Church whose duty it was to ferret out delinquents in morals, especially in matters of fornication and adultery, and to bring them before the ecclesiastical courts. This figure was the most hated and feared church official in the Middle Ages, and Chaucer's picture is unusually caustic. The Summoner had, from old acquaintance, whores and bawds as his agents, who informed him of all their clients, whether it was 'Sir Robert or Sir Huwe, or Jakke, or Rauf'. But for a quart ofwine or a purse he might allow a fellow to have his concubine a while. And yet, Chaucer says that this man himself was as hot and lecherous as a sparrow, a man who 'ful prively a fynch eek koude he pulle'.1 To round out the picture, the Summoner suffered from an unusually virulent disease: A Somonour was ther with us in that place, That hadde a fyr-reed cherubynnes face, For saucefleem he was, with eyen narwe. As hoot he was and lecherous as a sparwe, With scalled browes blake and piled berd. -

Medical Literacy in Medieval England and the Erasure of Anglo-Saxon Medical Knowledge

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: LINGUISTIC ORPHAN: MEDICAL LITERACY IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND THE ERASURE OF ANGLO-SAXON MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE Margot Rochelle Willis, Master of Arts in History, 2018 Thesis Directed By: Dr. Janna Bianchini, Department of History This thesis seeks to answer the question of why medieval physicians “forgot” efficacious medical treatments developed by the Anglo-Saxons and how Anglo- Saxon medical texts fell into obscurity. This thesis is largely based on the 2015 study of Freya Harrison et al., which replicated a tenth-century Anglo-Saxon eyesalve and found that it produced antistaphylococcal activity similar to that of modern antibiotics. Following an examination of the historiography, primary texts, and historical context, this thesis concludes that Anglo-Saxon medical texts, regardless of what useful remedies they contained, were forgotten primarily due to reasons of language: the obsolescence of Old English following the Norman Conquest, and the dominance of Latin in the University-based medical schools in medieval Europe. LINGUISTIC ORPHAN: MEDICAL LITERACY IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND THE ERASURE OF ANGLO-SAXON MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE by Margot Rochelle Willis Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History 2018 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Janna Bianchini, Chair Associate Professor Antoine Borrut Professor Mary Francis Giandrea © Copyright by Margot Rochelle Willis 2018 Dedication To my parents, without whose encouragement I would have never had the courage to make it where I am today, and who have been lifelong sources of support, guidance, laughter, and love. -

Medieval Medical Authorities

Medieval medical authorities Hippocrates, 450-370 BC, b. island of Cos, where he founded a medical school. He believed in observation and study of the body and that illness had a rational explanation. He treated holistically and considered diet, rest, fresh air and hygiene to be important for individuals. He also noted that illnesses presented in different degrees of severity from one individual to another and that people responded differently to illness and disease. He connected thought, ideas and feelings with the brain rather than the heart. His main works were the Aphorisms, Diagnostics and Prognostics. From the time of Galen, the Aphorisms were divided into 7 books and were central to the Articella, the basis of advanced teaching in Europe for four centuries from the twelfth. Hippocrates developed the eponymous oath of medical ethics. He is still known as the ‘Father of Medicine’. Claudius Galen, c. 130 AD, studied in Greece, Alexandria and other parts of Asia Minor. He became chief physician to the gladiator school at Pergamum where he gained experience in the treatment of wounds! From the 160s he worked at Rome where he became physician to the Emperor Marcus Aurelius. He was the first to dissect animals in order to understand the functions of the body and made several important discoveries, e.g. that urine formed in the kidneys and that the arteries carry blood; but he didn’t discover circulation. Galen collated all significant Greek and Roman medical thought up to his own time, adding his own discoveries and theories. The concept of the innate heat of the body was one of the enduring theories in medieval medicine ─ Galen believed that women were naturally colder than men. -

Medicine Or Magic? Physicians in the Middle Ages William Gries La Salle University, [email protected]

The Histories Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 8 2019 Medicine or Magic? Physicians in the Middle Ages William Gries La Salle University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Gries, William (2019) "Medicine or Magic? Physicians in the Middle Ages," The Histories: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories/vol15/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH stories by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Medicine or Magic? Physicians in the Middle Ages by William Gries According to Hannam’s paraphrase of the subject in The Genesis of Science: How the Christin Middle Ages Launched the Scientific Revolution, Aristotle claimed that, “no object could continue moving without some object moving it.”1 Such an observation may seem quite obvious to the uniformed observer, for, when one stops pushing a chair, the chair stops moving. This theory bumps into some problems, however, when it is extrapolated to all types of motion, such as a thrown ball that continues to move even after it has left the hand of the thrower. To make such an anomaly fit in with his theory of motion, Aristotle, “was convinced that something must be pushing it after it had left [one’s] hand…the only thing he could think of was that the air behind the ball was propelling it forward.”2 Now, modern science, the product of the Renaissance and Scientific Revolution in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, tells any learned person today that these Aristotelian claims are quite wrong. -

Habitus and Embodied Virtue in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Quidditas Volume 31 Article 5 2010 The Right Stuff: Habitus and Embodied Virtue in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Alice F. Blackwell Louisiana State University, Alexandria Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Blackwell, Alice F. (2010) "The Right Stuff: Habitus and Embodied Virtue in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight," Quidditas: Vol. 31 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol31/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 77 The Right Stuff: Habitus and Embodied Virtue in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Alice F. Blackwell Louisiana State University, Alexandria One of the themes weaving in and out of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is that of virtue: Gawain’s shield proclaims his virtue, yet at the end of the Green Chapel scene, he exclaims vice has destroyed his virtue, leaving him “faulty and false.” This scene has troubled critics and students, however, for many consider his reaction excessive for his default on the rules of a courtly game. The present paper contends that the notion of virtue written for Gawain naturalizes embodied virtue. While both religious and lay writers tended to argue that one possessed predisposition to moral or political virtue at birth, both camps strenuously argued that the individual must choose to develop these virtues, often through disciplining the body and mind. -

Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 Pm Page 23

001_025 (Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 pm Page 23 ENTRIES BY THEME Apparatus, Equipment, Implements, Techniques Weights and measures Agriculture Windmills Alum Arms and armor Biography Artillery and fire arms Abelard, Peter Brewing Abraham bar Hiyya Bridges Abu Ma‘shar al Balkh (Albumasar) Canals Adelard of Bath Catapults and trebuchets Albert of Saxony Cathedral building Albertus Magnus Clepsydra Alderotti, Taddeo Clocks and timekeeping Alfonso X the Wise Coinage, Minting of Alfred of Sareschel Communication Andalusi, Sa‘id al- Eyeglasses Aquinas, Thomas Fishing Archimedes Food storage and preservation Arnau de Vilanova Gunpowder Bacon, Roger Harnessing Bartholomaeus Anglicus House building, housing Bartholomaeus of Bruges Instruments, agricultural Bartholomaeus of Salerno Instruments, medical Bartolomeo da Varignana Irrigation and drainage Battani, al- (Albategnius) Leather production Bede Military architecture Benzi, Ugo Navigation Bernard de Gordon Noria Bernard of Verdun Paints, pigments, dyes Bernard Silvester Paper Biruni, al- Pottery Boethius Printing Boethius of Dacia Roads Borgognoni, Teodorico Shipbuilding Bradwardine, Thomas Stirrup Bredon, Simon Stone masonry Burgundio of Pisa Transportation Buridan, John Water supply and sewerage Campanus de Novara Watermills Cecco d’Ascoli xxiii 001_025 (Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 pm Page 24 xxii ENTRIES BY THEME Chaucer, Geoffrey John of Saint-Amand Columbus, Christopher John of Saxony Constantine the African John of Seville Despars, Jacques Jordanus de Nemore Dioscorides Khayyam, al- Eriugena, -

The Transmission of Learned Medical Literature in the Middle English Liber Uricrisiarum

Medical History, 1993, 37: 313-329. THE TRANSMISSION OF LEARNED MEDICAL LITERATURE IN THE MIDDLE ENGLISH LIBER URICRISIARUM by JOANNE JASIN * The Liber uricrisiarum in Wellcome MS 225 (hereafter, MS 225), a uroscopic treatise in Middle English that cites the De urinis by Isaac Judaeus as its principal source,' exemplifies the sort of vernacular medical literature produced in abundance in late fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century England that relies heavily on learned medical literature for its content.' Especially striking in the Liber uricrisiarum are both the numerous citations throughout the text of other medical and scientific authorities and the parallels between these citations and the texts required for medical study at university in the fourteenth century. The fact that vernacular medical literature in medieval Europe is based largely on authoritative medical and scientific texts as opposed to popular medical lore is nothing new;3 moreover, it is evident that the use of the vernacular, i.e., Middle English, expanded the reading audience to include lay medical practitioners as well as university-educated physicians.4 What the * Joanne Jasin, Ph.D., Department of English and Comparative Literature, California State University, Fullerton, California 92634, U.S.A. This article, printed here in revised form, was originally presented as a paper under the title 'Vernacular medical texts in medieval England' in the colloquium series 'New findings in the history of science' ('Neue Ergebnisse der Wissenschaftsgeschichte') at the Institute for the History of Medicine of the Free University, Berlin, 27 June 1991. I am grateful to Gerhard Baader for his valuable advice concerning the scope of this discussion in general and the issues of university curricula, Roger Frugardi, and the Anatoinia vivorum in particular. -

Etk/Evk Namelist

NAMELIST Note that in the online version a search for any variant form of a name (headword and/or alternate forms) must produce all etk.txt records containing any of the forms listed. A. F. H. V., O.P. Aali filius Achemet Aaron .alt; Aaros .alt; Arez .alt; Aram .alt; Aros philosophus Aaron cum Maria Abamarvan Abbo of Fleury .alt; Abbo Floriacensis .alt; Abbo de Fleury Abbot of Saint Mark Abdala ben Zeleman .alt; Abdullah ben Zeleman Abdalla .alt; Abdullah Abdalla ibn Ali Masuphi .alt; Abdullah ibn Ali Masuphi Abel Abgadinus Abicrasar Abiosus, John Baptista .alt; Abiosus, Johannes Baptista .alt; Abiosus, Joh. Ablaudius Babilonicus Ableta filius Zael Abraam .alt; Abraham Abraam Iudeus .alt; Abraam Iudeus Hispanus .alt; Abraham Iudeus Hispanus .alt; Abraam Judeus .alt; Abraham Iudaeus Hispanus .alt; Abraham Judaeus Abracham .alt; Abraham Abraham .alt; Abraam .alt; Abracham Abraham Additor Abraham Bendeur .alt; Abraham Ibendeut .alt; Abraham Isbendeuth Abraham de Seculo .alt; Abraham, dit de Seculo Abraham Hebraeus Abraham ibn Ezra .alt; Abraham Avenezra .alt; ibn-Ezra, Avraham .alt; Aben Eyzar ? .alt; Abraham ben Ezra .alt; Abraham Avenare Abraham Iudaeus Tortuosensis Abraham of Toledo Abu Jafar Ahmed ben Yusuf ibn Kummed Abuali .alt; Albualy Abubacer .alt; Ibn-Tufail, Muhammad Ibn-Abd-al-Malik .alt; Albubather .alt; Albubather Alkasan .alt; Abu Bakr Abubather Abulhazen Acbrhannus Accanamosali .alt; Ammar al-Mausili Accursius Parmensis .alt; Accursius de Parma Accursius Pistoriensis .alt; Accursius of Pistoia .alt; M. Accursium Pistoriensem -

Syon Abbey: Its Herbal, Medical Books and Care of the Sick: Healthcare in a Mixed Mediaeval Monastery

Syon Abbey: Its Herbal, Medical Books and Care of the Sick: Healthcare in a Mixed Mediaeval Monastery. By John Adams, Syon Abbey Research Associates This work may be freely cited as: ADAMS, J. S. (2015) Syon Abbey: Its Herbal, Medical Books and Care of the Sick: Healthcare in a Mixed Mediaeval Monastery 1 CONTENTS Syon Abbey: Its Medical Books, Herbal and Healthcare Pages 3 to 84 Medical Books in the Syon Registrum Section B and SS2 Pages 85 to 118 Details on Donors of Medical Books Pages 119 to 122 List of Manuscripts Consulted or Cited Pages 123 to 124 Text From Joseph Strutt’s, Bibliographical Dictionary (1785) Pages 125 to 126 (to accompany Image of Thomas Betson in text at page 12) Select Bibliography Pages 127 to 141 2 Syon Abbey: Its Medical Books and Care of the Sick1 1 Syon Abbey: A Brief History. The reasons for the unlikely founding in 1415 of a Swedish abbey of 60 nuns and 25 brothers to the west of London by Henry V (1387-1422) are to be sought in the bitter struggle between France and England during the Hundred Years’ War. This war had effectively begun in May 1337, with the seizure of the continental possessions of Edward III of England (1312-1377) by Philippe VI of France (1293- 1350). This act led directly to the Battle of Crécy in 1346, in which Edward III destroyed the French army, killing many of the nobility. It was probably following this battle that Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373), a powerful and inspired voice in the Europe of the time, claimed to have received guidance from Christ himself, calling for a dynastic marriage between the French and English royal houses, so that the dual inheritance would fall to a legitimate heir, and thus end the wars.2 This appeal, which was sent to Pope Clement VI (from 1342 to 1352), was transmitted to England by King Magnus IV of Sweden (1316-1374) in 1348.3 But it was, perhaps not surprisingly, picked up and used by English polemicists as supporting England’s claim to France. -

Blood and Spirituality in Late Medieval English Literary Culture

The Seat of the Soul: Blood and Spirituality in Late Medieval English Literary Culture By Sarah Star A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Sarah Star 2016 The Seat of the Soul: Blood and Spirituality in Late Medieval English Literary Culture Sarah Star Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2016 Abstract My dissertation uncovers the ways that medieval literature both shares a physiological vocabulary with medieval English medicine and extends it. I argue that medieval romances, devotional prose tracts, and dramatic works all use a specifically physiological language to represent transformative miracles. At the same time that these texts use this vocabulary, however, they also do what medicine cannot: medieval literature, I argue, complicates and extends its physiological background in order to represent religious identities, mark religious difference, and explain the inextricability of physical and spiritual life. To establish an intellectual context for my analysis, I examine the earliest known academic medical treatise written in English: the Liber Uricrisiarum (c. 1379) by Dominican friar, Henry Daniel. Daniel’s treatise serves not as a singular source for the medical ideas discussed here but rather as a contemporary intertext that shares a physiological language with literature and that intersects with medieval literary culture in its distinctly vernacular style. The succeeding chapters focus on the role of blood in providing physical form and conferring religious identity in the anonymous King of Tars, Julian of Norwich’s Revelation of Love, and the N-Town Nativity play. -

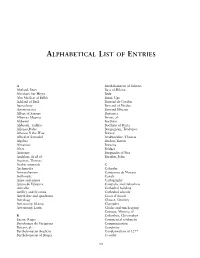

A-Z Entries List

001_025 (Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 pm Page 19 ALPHABETICAL LIST OF ENTRIES A Bartholomaeus of Salerno Abelard, Peter Bayt al-Hikma Abraham bar Hiyya Bede Abu Ma’shar al Balkh Benzi, Ugo Adelard of Bath Bernard de Gordon Agriculture Bernard of Verdun Agrimensores Bernard Silvester Albert of Saxony Bestiaries Albertus Magnus Biruni, al- Alchemy Boethius Alderotti, Taddeo Boethius of Dacia Alfonso,Pedro Borgognoni, Teodorico Alfonso X the Wise Botany Alfred of Sareschel Bradwardine, Thomas Algebra Bredon, Simon Almanacs Brewing Alum Bridges Anatomy Burgundio of Pisa Andalusi, Sa‘id al- Buridan, John Aquinas, Thomas Arabic numerals C Archimedes Calendar Aristotelianism Campanus de Novara Arithmetic Canals Arms and armor Cartography Arnau de Vilanova Catapults and trebuchets Articella Cathedral building Artilley and firearms Cathedral schools Astrolabes and quadrants Cecco d’Ascoli Astrology Chauce, Geoffrey Astronomy, Islamic Clepsydra Astronomy, Latin Clocks and timekeeping Coinage, Minting of B Columbus, Christopher Bacon, Roger Commercial arithmetic Bartolomeo da Varignana Communication Battani, al- Computus Bartholomaeus Anglicus Condemnation of 1277 Bartholomaeus of Bruges Consilia xix 001_025 (Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 pm Page 20 xx ALPHABETICAL LIST OF ENTRIES Constantine the African I Cosmology Ibn al-Haytham Ibn al-Saffar D Ibn al-Samh Despars, Jacques Ibn al-Zarqalluh Dioscorides Ibn Buklarish Duns Scotus, Johannes Ibn Ezra, Abraham Ibn Gabirol E Ibn Majid, Ahmad Elements and qualities Ibn Rushd Encyclopaedias Ibn Sina Eriugena,