Part C – Secwepemc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Nation Address List

(Version: November 16 05) KAMLOOPS FOREST DISTRICT - FIRST NATION ADDRESS LIST I. SHUSWAP NATION TRIBAL COUNCIL (SNTC): Shuswap Nation Tribal Council Neskonlith Indian Band (Sk’emtsin) Chair Chief Nathan Matthew Chief Art Anthony and Council Suite #304-355 Yellowhead Highway P.O. Box 608 Kamloops, B.C. #33 Chief Neskonlith Rd V2H 1H1 Chase, B.C. Ph (250) 828- 9789 V0E 1M0 Fax (250) 374-6331 Ph (250) 679-3295 Fax (250) 679-5306 AOA Contact: Chief Art Anthony, Sharon Jules Adams Lake Indian Band (Sexqeltqi’n) Simpcw First Nation Chief Ron Jules and Council (North Thompson Indian Band) P.O. Box 588 Chief Nathan Matthew and Council Chase, B.C. P.O. Box 220 V0E 1M0 500 Dunn Lake Road Ph (250) 679-8841 Barriere, B.C. Fax (250) 679-8813 V0E 1E0 Cc Dave Nordquist, Natural Resources Manager Ph (250) 672-9995 AOA Contact: Dave Nordquist Fax (250) 672-5858 AOA Contact: Nancy Jules; Joe Jules Bonaparte Indian Band (St’uxwtews) Skeetchestn Indian Band Chief Mike Retasket and Council Chief Ed Jules and Council P.O. Box 669 330 Main Drive Cache Creek, B.C. Box 178 V0K 1H0 Savona, B.C. Ph:(250) 457-9624 V0E 2J0 Fax (250) 457-9550. Has FRA Ph (250) 373-2493 AOA Contact: Chief Mike Retasket; Bert Fax (250) 373-2494 Williams AOA Contact: Mike Anderson; Lea McNabb High Bar Indian Band Spallumcheen Band (Splats’in) Chief Lenora Fletcher and Council Chief Gloria Morgan and Council P.O. Box 458 5775 Old Vernon Road Clinton, BC Box 460) V0K 1K0 Enderby, B.C. -

FNESS Strategic Plan

Strategic Plan 2013-2015 At a Glance FNESS evolved from the Society of Native Indian Fire Fighters of BC (SNIFF), which was established in 1986. SNIFF’s initial objectives were to help reduce the number of fire-related deaths on First Nations reserves, but it changed its emphasis to incorporate a greater spectrum of emergency services. In 1994, SNIFF changed its name to First Nations’ Emergency Services Society of BC to reflect the growing diversity of services it provides. Today our organization continues to gain recognition and trust within First Nations communities and within Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) and other organizations. This is reflected in both the growing demand of service requests from First Nations communities and the development of more government-sponsored programs with FNESS. r e v Ri k e s l A Inset 1 Tagish Lake Teslin 1059 Daylu Dena Atlin Lake 501 Taku River Tlingit r e v Liard Atlin Lake i R River ku 504 Dease River K Fort a e Nelson T r t 594 Ts'kw'aylaxw e c iv h R ik River 686 Bonaparte a se a 687 Skeetchestn e D Fort Nelson R i v e First Nations in 543 Fort Nelson Dease r 685 Ashcroft Lake Dease Lake 592 Xaxli'p British Columbia 593 T'it'q'et 544 Prophet River 591 Cayoose Creek 692 Oregon Jack Creek 682 Tahltan er 683 Iskut a Riv kw r s e M u iv R Finlay F R Scale ra e n iv s i er 610 Kwadacha k e i r t 0 75 150 300 Km S 694 Cook's Ferry Thutade R r Tatlatui Lake i e 609 Tsay Keh Dene v Iskut iv 547 Blueberry River e R Lake r 546 Halfway River 548 Doig River 698 Shackan Location -

KI LAW of INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law Of

KI LAW OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law of indigenous peoples Class here works on the law of indigenous peoples in general For law of indigenous peoples in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, see KIA20.2-KIA8900.2 For law of ancient peoples or societies, see KL701-KL2215 For law of indigenous peoples of India (Indic peoples), see KNS350-KNS439 For law of indigenous peoples of Africa, see KQ2010-KQ9000 For law of Aboriginal Australians, see KU350-KU399 For law of indigenous peoples of New Zealand, see KUQ350- KUQ369 For law of indigenous peoples in the Americas, see KIA-KIX Bibliography 1 General bibliography 2.A-Z Guides to law collections. Indigenous law gateways (Portals). Web directories. By name, A-Z 2.I53 Indigenous Law Portal. Law Library of Congress 2.N38 NativeWeb: Indigenous Peoples' Law and Legal Issues 3 Encyclopedias. Law dictionaries For encyclopedias and law dictionaries relating to a particular indigenous group, see the group Official gazettes and other media for official information For departmental/administrative gazettes, see the issuing department or administrative unit of the appropriate jurisdiction 6.A-Z Inter-governmental congresses and conferences. By name, A- Z Including intergovernmental congresses and conferences between indigenous governments or those between indigenous governments and federal, provincial, or state governments 8 International intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) 10-12 Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) Inter-regional indigenous organizations Class here organizations identifying, defining, and representing the legal rights and interests of indigenous peoples 15 General. Collective Individual. By name 18 International Indian Treaty Council 20.A-Z Inter-regional councils. By name, A-Z Indigenous laws and treaties 24 Collections. -

Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan for the Shuswap Lakes, BC

Final Report November 7th 2010 Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan for the Shuswap Lakes, BC Prepared for the: Fraser Basin Council Kamloops, BC Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan for the Shuswap Lakes, BC Prepared for the: Fraser Basin Council Kamloops, BC Prepared by: Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. 30 Gostick Place North Vancouver, BC V7M 3G3 Final Report November 7th 2010 Project 35138 DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. in accordance with generally accepted engineering and geoscience practices and is intended for the exclusive use and benefit of the client for whom it was prepared and for the particular purpose for which it was prepared. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made. Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. and its officers, directors, employees, and agents assume no responsibility for the reliance upon this document or any of its contents by any party other than the client for whom the document was prepared. The contents of this document are not to be relied upon or used, in whole or in part, by or for the benefit of others without specific written authorization from Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. and our client. Report prepared by: Ken I. Ashley, Ph.D., Senior Scientist Ken J. Hall, Ph.D. Associate Report reviewed by: Barry Chilibeck, P.Eng. Principal Engineer NHC. 2010. Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan for the Shuswap Lakes, BC. Prepared for the Fraser Basin Council. November 7thth, 2010. © copyright 2010 Shuswap Lake Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan i CREDITS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to acknowledge to Mike Crowe (DFO, Kamloops), Ian McGregor (Ministry of Environment, Kamloops), Phil Hallinan (Fraser Basin Council, Kamloops) and Ray Nadeau (Shuswap Water Action Team Society) for supporting the development of the Shuswap Lakes water quality monitoring plan. -

The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: the Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper

Journal of Indigenous Research Full Circle: Returning Native Research to the People Volume 8 Issue 2020 March 2020 Article 1 March 2020 The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper Jason W. Johnston Thompson Rivers University, [email protected] Courtney Mason Thompson Rivers University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir Recommended Citation Johnston, Jason W. and Mason, Courtney (2020) "The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper," Journal of Indigenous Research: Vol. 8 : Iss. 2020 , Article 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26077/7t6x-ds86 Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol8/iss2020/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Indigenous Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper Cover Page Footnote To the Indigenous participants and the participants from Jasper National Park, thank you. Without your knowledge, passion and time, this project would not have been possible. While this is only the beginning, your contributions to this work will lead to a deeper understanding and appreciation for the complexities of the issues surrounding Indigenous representation in national parks. This article is available in Journal of Indigenous Research: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol8/iss2020/1 Johnston and Mason: The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper National parks hold an important place in the identities of many North Americans. -

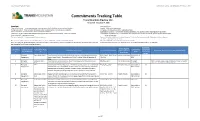

Commitments Tracking Table Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Version 20 - December 7, 2018

Trans Mountain Expansion Project Commitment Tracking Table (Condition 6), December 7, 2018 Commitments Tracking Table Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Version 20 - December 7, 2018 Project Stage Commitment Status "Prior to Construction" - To be completed prior to construction of specific facility or relevant section of pipeline "Scoping" - Work has not commenced "During Construction" - To be completed during construction of specific facility or relevant section of pipeline "In Progress - Work has commenced or is partially complete "Prior to Operations" - To be completed prior to commencing operations "Superseded by Condition" - Commitment has been superseded by NEB, BC EAO condition, legal/regulatory requirement "Operations" - To be completed after operations have commenced, including post-construction monitoring conditions "Superseded by Management Plan" - Addressed by Trans Mountain Policy or plans, procedures, documents developed for Project "Project Lifecycle" - Ongoing commitment design and execution "No Longer Applicable" - Change in project design or execution "Superseded by TMEP Notification Task Force Program" - Addressed by the project specific Notification Task Force Program "Complete" - Commitment has been met Note: Red text indicates a change in Commitment Status or a new Commitment, from the previously filed version. "No Longer Applicable" - Change in project design or execution Note: As of August 31, 2018, Kinder Morgan ceased to be an owner of Trans Mountain. References to Kinder Morgan Canada or KMC in the table below have -

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

Indian Band Revenue Moneys Order Décret Sur Les Revenus Des Bandes D’Indiens

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Indian Band Revenue Moneys Décret sur les revenus des Order bandes d’Indiens SOR/90-297 DORS/90-297 Current to October 11, 2016 À jour au 11 octobre 2016 Last amended on December 14, 2012 Dernière modification le 14 décembre 2012 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

The Wealth of First Nations

The Wealth of First Nations Tom Flanagan Fraser Institute 2019 Copyright ©2019 by the Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief passages quoted in critical articles and reviews. The author of this book has worked independently and opinions expressed by him are, there- fore, his own and and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, its Board of Directors, its donors and supporters, or its staff. This publication in no way implies that the Fraser Institute, its directors, or staff are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill; or that they support or oppose any particular political party or candidate. Printed and bound in Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data The Wealth of First Nations / by Tom Flanagan Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-88975-533-8. Fraser Institute ◆ fraserinstitute.org Contents Preface / v introduction —Making and Taking / 3 Part ONE—making chapter one —The Community Well-Being Index / 9 chapter two —Governance / 19 chapter three —Property / 29 chapter four —Economics / 37 chapter five —Wrapping It Up / 45 chapter six —A Case Study—The Fort McKay First Nation / 57 Part two—taking chapter seven —Government Spending / 75 chapter eight —Specific Claims—Money / 93 chapter nine —Treaty Land Entitlement / 107 chapter ten —The Duty to Consult / 117 chapter eleven —Resource Revenue Sharing / 131 conclusion —Transfers and Off Ramps / 139 References / 143 about the author / 161 acknowledgments / 162 Publishing information / 163 Purpose, funding, & independence / 164 About the Fraser Institute / 165 Peer review / 166 Editorial Advisory Board / 167 fraserinstitute.org ◆ Fraser Institute Preface The Liberal government of Justin Trudeau elected in 2015 is attempting massive policy innovations in Indigenous affairs. -

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expension Project

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project November 2016 Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the TRANS MOUNTAIN EXPANSION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms, Abbreviations and Definitions Used in This Report ...................... xi 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Report ..............................................................................1 1.2 Project Description .................................................................................2 1.3 Regulatory Review Including the Environmental Assessment Process .....................7 1.3.1 NEB REGULATORY REVIEW AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ....................7 1.3.2 BRITISH COLUMBIA’S ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ...............................8 1.4 NEB Recommendation Report.....................................................................9 2. APPROACH TO CONSULTING ABORIGINAL GROUPS ........................... 12 2.1 Identification of Aboriginal Groups ............................................................. 12 2.2 Information Sources .............................................................................. 19 2.3 Consultation With Aboriginal Groups ........................................................... 20 2.3.1 PRINCIPLES INVOLVED IN ESTABLISHING THE DEPTH OF DUTY TO CONSULT AND IDENTIFYING THE EXTENT OF ACCOMMODATION ........................................ 24 2.3.2 PRELIMINARY -

Appendix 22-A

Appendix 22-A Simpcw First Nation Traditional Land Use and Ecological Knowledge Study HARPER CREEK PROJECT Application for an Environmental Assessment Certificate / Environmental Impact Statement SIMPCW FIRST NATION FINAL REPORT PUBLIC VERSION Traditional Land Use & Ecological Knowledge STUDY REGARDINGin THE PROPOSED YELLOWHEAD MINING INC. HARPER CREEK MINE Prepared by SFN Sustainable resources Department August 30, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Research Team would like to thank the Simpcw First Nation (SFN), its elders, members, and leadership For the trust you’ve placed in us. We recognize all community members who contributed their knowledge oF their history, culture and territory to this work. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The report has been the product oF a collaborative eFFort by members oF the research team and as such is presented in more than one voice. The Simpcw First Nation Traditional Land Use and Ecological Knowledge Study presents evidence oF Simpcw First Nation (SFN) current and past uses oF an area subject to the development oF the Harper Creek Mine by Yellowhead Mining, Inc. The report asserts that the Simpcw hold aboriginal title and rights in their traditional territory, including the land on which the Harper Creek Mine is proposed. This is supported by the identiFication oF one hundred and Four (104) traditional use locations in the regional study area (Simpcwul’ecw; Simpcw territory) and twenty (20) sites in the local study area. The traditional use sites identiFied, described, and mapped during this study conFirm Simpcw connections to the area where the Harper Creek Mine is proposed. These sites include Food harvesting locations like hunting places, Fishing spots, and plant gathering locations. -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov.