Vocal Persona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mad Radio 106,2

#WhoWeAre To become the largest Music Media and Services organization in the countries we operate, providing services and products which cover all communication & media platforms, satisfying directly and efficiently both our client’s and our audience’s needs, maintaining at the same time our brand's creative and subversive character. #MISSION #STRUCTURE NEW MEDIA TV EVENTS RADIO WEB INTERNATIONAL & SERVICES MAD 106,2 Mad TV www.mad.gr DIGITAL VIDEO MUSIC MadRADIO Mad TV CYPRUS GREECE MARKETING AWARDS Mad HITS/ CONTENT Mad TV MADWALK 104FM SOCIAL MEDIA OTE Conn-x SERVICES ALBANIA Mad GREEKζ/ MAD MUSIC ANTENNA EUROSONG NOVA @NOVA SATELLITE MAD PRODUCTION NORTH STAGE Dpt FESTIVAL YouTube #TV #MAD TV GREECE • Hit the airwaves on June 6th, 1996 • One of the most popular music brands in Greece*(Focus & Hellaspress) • Mad TV has the biggest digital database of music content in Greece: –More than 20.000 video clips –250.000 songs –More than 1.300 hours of concerts and music documentaries –Music content database with tens of thousands music news, biographical information –and photographic material of artists, wallpapers, ring tones etc. • Mad TV has deployed one of the most advanced technical infrastructures and specialized IT/Technical/ Production teams in Greece. • Mad TV Greece is available on free digital terrestrial, cable, IPTV, satellite and YouTube all over Greece. #PROGRAM • 24/7 youth program • 50% International + 50% Greek Music • All of the latest releases from a wide range of music genres • 30 different shows/ week (21 hours of live -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2017 "You Will Hold This Book in Your Hands": The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology Jason Shrontz University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Shrontz, Jason, ""You Will Hold This Book in Your Hands": The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology" (2017). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 558. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/558 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “YOU WILL HOLD THIS BOOK IN YOUR HANDS”: THE NOVEL AND CORPOREALITY IN THE NEW MEDIA ECOLOGY BY JASON SHRONTZ A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF JASON SHRONTZ APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Jeremiah Dyehouse Ian Reyes Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the relationship between the print novel and new media. It argues that this relationship is productive; that is, it locates the novel and new media within a tense, but symbiotic relationship. This requires an understanding of media relations that is ecological, rather than competitive. More precise, this dissertation investigates ways that the novel incorporates new media. The word “incorporate” refers both to embodiment and physical union. -

Humour Investigation: an Analysis of the Theoretical Humour Perspectives, Cultural Continuities, and Developmental Aspects Related to the Comedy of Dawn French

Humour Investigation: An Analysis of the Theoretical Humour Perspectives, Cultural Continuities, and Developmental Aspects Related to the Comedy of Dawn French Thursday, 10 May 2007 Nationally acclaimed former cartoonist and short story writer for The New Yorker, James Thurber, said that “the wit makes fun of other persons; the satirist makes fun of the world; [and] the humorist makes fun of himself” (Moncur, 2007, p. 1). Despite his misogynistic pronoun usage and the obviously unforgivable atrocity of overly Americanizing the spelling of 'humourist,' he did nicely categorize three of the methodological approaches to comedic targets. What Thurber didn't account for, however, were those comedians and comediennes who pay little to no regard for the socially constructed boundaries in form; he didn't account for the wildly transcendental Dawn French. Dawn French was born in October of 1957 in Wales and since early adulthood she has honed her humour skills through numerous television performances, a largely successful sitcom, and feature-length films with her comedic partner in crime Jennifer Saunders (Wikipedia, 2007). Though she started her career in a non- mainstream vain of comedy in the UK, her first major public debut was her starring role as Geraldine Granger on BBC1's 1990s smash situational comedy, The Vicar of Dibley (Wikipedia, 2007). Thus, the majority of her comedy has taken place in very recent times—the mid-to-late 90s and on into the current decade. While she utilizes many different comedic modes and forms, French's humour largely revolves around a few central themes and consequent philosophies. When investigating those themes, it is necessary to view her career as being dichotomously split into the Vicar of Dibley era and the subsequent post-Vicar epoch. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 20/12/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 20/12/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Perfect - Ed Sheeran Grandma Got Run Over By A Reindeer - Elmo & All I Want For Christmas Is You - Mariah Carey Summer Nights - Grease Crazy - Patsy Cline Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Feliz Navidad - José Feliciano Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas - Michael Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Killing me Softly - The Fugees Don't Stop Believing - Journey Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Zombie - The Cranberries Baby, It's Cold Outside - Dean Martin Dancing Queen - ABBA Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Rockin' Around The Christmas Tree - Brenda Lee Girl Crush - Little Big Town Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi White Christmas - Bing Crosby Piano Man - Billy Joel Jackson - Johnny Cash Jingle Bell Rock - Bobby Helms Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Baby It's Cold Outside - Idina Menzel Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Let It Go - Idina Menzel I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Last Christmas - Wham! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! - Dean Martin You're A Mean One, Mr. Grinch - Thurl Ravenscroft Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Africa - Toto Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer - Alan Jackson Shallow - A Star is Born My Way - Frank Sinatra I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor The Christmas Song - Nat King Cole Wannabe - Spice Girls It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas - Dean Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Please Come Home For Christmas - The Eagles Wagon Wheel - -

Spring 2007 Newsletter

Dance Studio Art Create/Explore/InNovate DramaUCIArts Quarterly Spring 2007 Music The Art of Sound Design in UCI Drama he Drama Department’s new Drama Chair Robert Cohen empa- a professor at the beginning of the year, graduate program in sound sized the need for sound design initia- brings a bounty of experience with him. design is a major step in the tive in 2005 as a way to fill a gap in “Sound design is the art of provid- † The sound design program Tdepartment’s continuing evolution as the department’s curriculum. “Sound ing an aural narrative, soundscape, contributed to the success of Sunday in The Park With George. a premier institution for stagecraft. design—which refers to all audio reinforcement or musical score for generation, resonation, the performing arts—namely, but not performance and enhance- limited to, theater,” Hooker explains. ment during theatrical or “Unlike the recording engineer or film film production—has now sound editor, we create and control become an absolutely the audio from initial concept right vital component” of any down to the system it is heard on.” quality production. He spent seven years with Walt “Creating a sound Disney Imagineering, where he designed design program,” he con- sound projects for nine of its 11 theme tinued, “would propel UCI’s parks. His projects included Cinemagique, Drama program—and the an interactive film show starring actor collaborative activities of Martin Short at Walt Disney Studios its faculty—to the high- Paris; the Mermaid Lagoon, an area fea- est national distinction.” turing several water-themed attractions With the addition of at Tokyo Disney Sea; and holiday overlays Michael Hooker to the fac- for the Haunted Mansion and It’s a Small ulty, the department is well World attractions at Tokyo Disneyland. -

Dispatches: Representatives

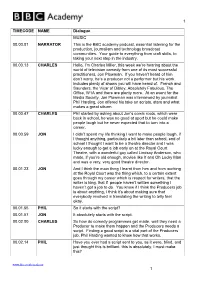

1 TIMECODE NAME Dialogue MUSIC 00.00.01 NARRATOR This is the BBC academy podcast, essential listening for the production, journalism and technology broadcast communities. Your guide to everything from craft skills, to taking your next step in the industry. 00.00.13 CHARLES Hello, I’m Charles Miller, this week we’re hearing about the world of television comedy from one of its most successful practitioners, Jon Plowman. If you haven’t heard of him don’t worry, he’s a producer not a performer but his work includes plenty of shows you will have heard of. French and Saunders, the Vicar of Dibley, Absolutely Fabulous, The Office, W1A and there are plenty more. At an event for the Media Society, Jon Plowman was interviewed by journalist Phil Harding, Jon offered his take on scripts, stars and what makes a great sitcom. 00.00.47 CHARLES Phil started by asking about Jon’s comic roots, which were back in school, he was no good at sport but he could make people laugh but he never expected that to turn into a career. 00.00.59 JON I didn’t spend my life thinking I want to make people laugh, if I thought anything, particularly a bit later than school, end of school I thought I want to be a theatre director and I was lucky enough to get a job early on at the Royal Court Theatre, with a wonderful guy called Lindsay Anderson, who made, if you’re old enough, movies like If and Oh Lucky Man and was a very, very good theatre director. -

Snow Patrol, Hands Open It's Hard to Argue When You Won't Stop Making Sense but My Tongue Still Misbehaves and It Keeps Digging My Own Grave with My

Snow Patrol, Hands Open It's hard to argue when you won't stop making sense But my tongue still misbehaves and it keeps digging my own grave with my Hands open, and my eyes open I just keep hoping That your heart opens Why would I sabotage the best thing that I have Well, it makes it easier to know exactly what I want with my... Hands open and my eyes open I just keep hoping that your heart opens It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy Put Sufjan Stevens on and we'll play your favorite song "Chicago" bursts to life and your sweet smile remembers you, my Hands open, and my eyes open I just keep hoping That your heart opens It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy Snow Patrol - Hands Open w Teksciory.pl. -

Stephen Colbert Joins Patrick Wilson, Warren Zanes to Headline the Glitter Ball: a Dance Floor Celebration of Soul, R&B, and Funk

For Immediate Release STEPHEN COLBERT JOINS PATRICK WILSON, WARREN ZANES TO HEADLINE THE GLITTER BALL: A DANCE FLOOR CELEBRATION OF SOUL, R&B, AND FUNK MORE SPECIAL GUESTS TO BE ANNOUNCED SOON! PROCEEDS TO BENEFIT MONTCLAIR FILM’S YEAR-ROUND FILM & EDUCATION PROGRAMS February 4, 2019, MONTCLAIR, NJ— Montclair Film today announced that Stephen Colbert will perform at The Glitter Ball: A Dance Floor Celebration Of Soul, R&B, and Funk featuring live music from Joe McGinty & the Loser’s Lounge, joining special performances from Patrick Wilson, Warren Zanes, and more special guests. The event takes place on Saturday, March 2, at 8:00 PM at The Wellmont Theater in Montclair, NJ. Proceeds from this special evening will support Montclair Film’s ongoing, year-round film and education programs. “We’re thrilled to have Stephen back with us and can’t wait for a great night,” said Montclair Film Executive Director Tom Hall. “This show will feature so many great sing- ers and musicians, a great opportunity to dance the night away and support a great cause.” Tickets for the event begin at $30 for The Concert Experience, featuring balcony seat- ing, with a $100 Dance Floor Experience on the main floor offering dancing and two complimentary drink tickets. A special VIP Dance Floor Experience ticket at $200 in- cludes a pre-show reception, with complimentary drinks and hors d'oeuvres throughout the entire event. All ticketing is General Admission and tickets are available beginning today at montclairfilm.org Key art for this event can be found at http://bit.ly/MF2019GlitterBall ABOUT JOE MCGINTY & THE LOSER’S LOUNGE Joe McGinty & the Loser’s Lounge are a collective of New York City’s finest performers who have been selling out live shows every other month for over twenty five years. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 11-17-2003 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2003). The George-Anne. 3041. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/3041 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. stablished 192; Covering the campus like a swarm of gnats The Official Student Newspaper oi Georgia Eagles win regular season finale over Elon 37-13 Page 6 * \? vSisnsmuSi 11th all those who serve our counti By Eric Haugh and Kim Wicker [email protected] and I Omber afternoon in the crowds of students, faculty, and veter- in i ithered in front of the IT Building for a color guard and banner display observing >y ie Veterans Day. The half-hour long procession, which started at 12:15 p.m. in front of Henderson library, was a silent but profound i ..salute to the flag, and th||§en and women who risked their lives (many losing theirs along the way) to preserve our wap of life. It was a touching ceremony; some of.the observers even . rapine misty-eyed towards||e end of the service, when Dr. White from the COBA buildihgaccepted a wreath from one [ of.the color guard members. -

Weekend Movie Schedule Photo Can Be Fixed

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, May 12, 2006 5 MONDAY EVENING MAY 15, 2006 brassiere). However, speaking as a 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 fellow sugar addict, my advice is to E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Photo can be fixed start cutting back on the sugar, be- The First 48: Twisted Tattoo Fixation Influences; Inked Inked Crossing Jordan (TV14) The First 48: Twisted 36 47 A&E DEAR ABBY: My husband, cause not only is it addictive, it also Honor; Vultures designs. (TVPG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (HD) Honor; Vultures abigail Oprah Winfrey’s Legends Grey’s Anatomy: Deterioration of the Fight or Flight KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live “Keith,” and I are eagerly awaiting makes you crave more and more. And 4 6 ABC an hour after you’ve consumed it, Ball (N) Response/Losing My Religion (N) (HD) at 10 (N) (TV14) the birth of our first child. Sadly, van buren Animal Precinct: New Be- Miami Animal Police: Miami Animal Police: Animal Precinct: New Be- Miami Animal Police: Keith’s mother is in very poor health. you’ll feel as fatigued as you felt “en- 26 54 ANPL ginnings (TV G) Gators Galore (TVPG) Gator Love Bite ginnings (TV G) Gators Galore (TVPG) ergized” immediately afterward. The West Wing: Tomor- “A Bronx Tale” (‘93, Drama) Robert De Niro. A ‘60s bus driver “A Bronx Tale” (‘93, Drama) A man She’s not expected to live more than 63 67 BRAVO a few months after the birth of her dear abby DEAR ABBY: I was adopted by a row (TVPG) (HD) struggles to bring up his son right amid temptations. -

Saturday and Sunday Movies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, June 17, 2005 5b abigail Simon’s college graduation. Bernice TEXAS stay-at-home mom with three kids. just tap right into his. Please help me. Husband not made dinner reservations for every- DEAR HAD ENOUGH: Whether Two are my fiance “Sean’s”; the I don’t know what to do. — SPEND- van buren one in the family and excluded my or not your marriage is salvageable littlest is ours together. Sean and I A-HOLIC IN VENTURA, CALIF. son and me. I told Simon how hurt I is up to your husband. You married have been together almost seven DEAR SPEND-A-HOLIC: It is able to stop his was. His response, “I can’t control a man with an impossible, domineer- years. time to stop and take inventory of •dear abby my mother.” ing and hostile mother. Forget that it I need help. I am a very depressed what you have and what you don’t. mother’s abuse Abby, I was so fed up with having takes “two to tango.” Because Simon person and have been for many You are substituting “things” for DEAR ABBY: I married the love ding, and I let Simon know it. I tried to swallow her abuse with no support hasn’t accepted his own responsibil- years. I shop excessively and spend something important that’s missing of my life, “Simon,” a year ago. At to forgive her. from my husband that I kicked him ity in the conception of this child, he way too much — sometimes all of in your life.