1 Introduction to 'Ideology' 2 Ideology and the Paradox of Subjectivity 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

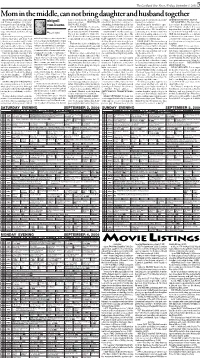

Saturday and Sunday Movies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, June 17, 2005 5b abigail Simon’s college graduation. Bernice TEXAS stay-at-home mom with three kids. just tap right into his. Please help me. Husband not made dinner reservations for every- DEAR HAD ENOUGH: Whether Two are my fiance “Sean’s”; the I don’t know what to do. — SPEND- van buren one in the family and excluded my or not your marriage is salvageable littlest is ours together. Sean and I A-HOLIC IN VENTURA, CALIF. son and me. I told Simon how hurt I is up to your husband. You married have been together almost seven DEAR SPEND-A-HOLIC: It is able to stop his was. His response, “I can’t control a man with an impossible, domineer- years. time to stop and take inventory of •dear abby my mother.” ing and hostile mother. Forget that it I need help. I am a very depressed what you have and what you don’t. mother’s abuse Abby, I was so fed up with having takes “two to tango.” Because Simon person and have been for many You are substituting “things” for DEAR ABBY: I married the love ding, and I let Simon know it. I tried to swallow her abuse with no support hasn’t accepted his own responsibil- years. I shop excessively and spend something important that’s missing of my life, “Simon,” a year ago. At to forgive her. from my husband that I kicked him ity in the conception of this child, he way too much — sometimes all of in your life. -

Saturday and Sunday Movies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, May 28, 2004 5 abigail your help, Abby — it’s been an aw- dinner in the bathroom with her. I behavior is inappropriate. Your parents remember leaving me home Co-worker ful burden. — OLD-FASHIONED find his behavior questionable and daughter is old enough to bathe with- alone at that age, but that was 24 van buren IN BOULDER have asked him repeatedly to allow out supervision and should do so. years ago. I feel things are too dan- DEAR OLD-FASHIONED: Talk her some privacy. Nonetheless, he You didn’t mention how physically gerous these days. creates more to the supervisor privately and tell continues to “assist her” in bathing developed she is, but she will soon Is there an age when I can leave •dear abby him or her what you have told me. by adding bath oil to the water, etc. be a young woman. Your husband’s them home alone and know that all work for others Say nothing to Ginger, because that’s Neither my husband nor my daugh- method of “lulling” her to sleep is is OK? — CAUTIOUS MOM IN DEAR ABBY: I work in a large, breaks, sometimes even paying her the supervisor’s job — and it will ter thinks anything is wrong with this also too stimulating for both of them. KANSAS open office with five other people. bills and answering personal corre- only cause resentment if you do. behavior — so what can I do? Discuss this with your daughter’s DEAR CAUTIOUS MOM: I’m We all collaborate on the same spondence on company time. -

CC Students Organize Venetucci Farm

Editor in Chief apologizes for T mistake in last issue’s Vanessa H Reichert-Fitzpatrick article E CATALYST PAGE 10 October 13, 2006 Est. 1969 Issue 5, Volume 52 Iraq War Memorial visits campus Anti-war stand Alex Emmons stirs controversy Staff Writer William Benét The war memorial exhibit Eyes Wide Open, a Staff Writer traveling demonstration of the cost of the Iraq Salida, CO citizen Debra Juchem painted an War in human casualties, came to Colorado anti-war sign on the facade of her downtown College Thursday, Oct. 12 and Friday, Oct. building last April. The sign read, “Kill one 13 in the form of over 2,500 pairs of combat person and it’s murder; kill thousands and boots representing fallen American soldiers. it’s foreign policy. Stop the Iraq War now!” Students and Colorado Springs citizens Over the course of the past several stopped to view the extensive lines of boots months, the sign has fomented considerable and the Wall of Remembrance, which backlash among this small mountain commemorates Iraqis who have died in the community of population 5,500, drawing war. in both city officials and the American Civil Eyes Wide Open (EWO) has toured over Liberties Union of Colorado. 100 cities since its creation two years ago. Sam Cornwall/Catalyst During the summer, fellow Salida The American Friends Service Committee Over 2,500 combat boots were displayed across Armstrong Quad on Thurs- citizen Rick Shovald went out to dinner originally created the memorial in Chicago day, Oct. 12 and Friday, Oct. 13 in memorial for Iraq War casualties. -

* TV-Filmresume-Letrhd

Glenn Berkovitz, CAS [email protected] 310- 902-1148 Production Sound Mixer Television programming: ANATOMY OF VIOLENCE (series pilot), 21st Century Fox Television/CBS - Dir.: Mark Pellington HOW TO LIVE WITH YOUR PARENTS (pilot + series), Fox Television/ABC - Prod: Claudia Lonow, Ken Ornstein, Mark Grossan THE SAINT (series pilot), Silver Screen Pictures - Dir.: Simon West BENT (series), NBC Universal Television/NBC - Prod.: Tad Quill, DJ Nash, Chris Plourde ZEKE & LUTHER (series - seasons 1, 2 & 3), Turtle Rock Pictures/Disney Channel - Prod.: Danielle Weinstock PARKS & RECREATION (series - pilot & season 1), NBC Television - Prod.: Morgan Sackett OCTOBER ROAD (series - season 2), Touchstone TV / ABC - Prod.: Scott Rosenberg, Mark Ovitz MEN OF A CERTAIN AGE (series pilot), Turner North / TNT Network - Dir.: Scott Winant COURTROOM K (series pilot), Fox Television - Dir.: Anthony & Joe Russo RAINES (series pilot), NBC Television/NBC - Dir.: Frank Darabont CAMPUS LADIES (series - 2 seasons), Principato/Young / Oxygen Network - Prod.: Paul Young, Brian Hall WEEDS (pilot + seasons 1 & 2), Lions Gate / Showtime Television - Exec. Prod.: Jenji Kohan, Mark Burley KAREN SISCO (series), Universal Television / ABC - Exec. Prod.: Bob Brush, Michael Dinner FOOTBALL WIVES (series pilot), Touchstone Television/ABC - Dir.: Bryan Singer HARRY GREEN AND EUGENE (series pilot), Paramount Pictures/ABC - Dir.: Simon West LUCKY (series), Castle Rock Television / F/X Networks - Exec. Prod.: Robb & Mark Cullen BOSTON LEGAL (assorted episodes), David E. Kelley Prod./Fox Television - Prod.: Bill D’Elia, Janet Knutsen CROSSING JORDAN (pilot + season 1), NBC Productions/NBC - Exec. Prod.: Tim Kring FREAKYLINKS (series), 20th Century Fox Television/Fox Broadcasting - Exec. Prod.: David Simkins M.Y.O.B. -

Believe: the Music of Cher Seattle Men's Chorus Encore Arts Seattle

MARCH 2019 the music of MARCH 30 & 31 | ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PAUL CALDWELL | SEATTLECHORUSES.ORG With the nation’s premier Cher impersonator and winner of RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars, CHAD MICHAELS BYLANDBYSEA BYEXPERTS With unmatched experience and insider knowledge, we are the Alaska experts. No other cruise line gives you more options to see Glacier Bay. Plus, only we give you the premier Denali National Park adventure at our own McKinley Chalet Resort combined with access to the majestic Yukon Territory. It’s clear, there’s no better way to see Alaska than with Holland America Line. Call your Travel Advisor or 1-877-SAIL HAL, or visit hollandamerica.com Ships’ Registry: The Netherlands HAL 14038-4 Alaska4up_SeattleChorus_V1.indd 1 2/12/19 5:04 PM Pub/s: Seattle Chorus Traffic: 2/12/19 Run Date: March Color: CMYK Author: SN Trim: 8.375"wx10.875"h Live: 7.375"w x 9.875"h Bleed: 8.625"w x 11.125"h Version#: 1 FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR I’ve said it before: refrains of hate and division that fall Seattle takes queens on the ears of his students every day. very seriously. If This was an invitation to do something RuPaul is on TV, different, something bold, something you can’t get a really beautiful. seat at any of So every winter, I go to the school the Capitol Hill weekly. But I don’t go alone. Singers establishments. from Seattle Men’s and Women’s Everything is jam-packed. And the Choruses take off work to be there exuberance of the fans rivals that of with me at 8:55 every Thursday the 12th man at a Seahawks game. -

Mom in the Middle, Can Not Bring Daughter and Husband Together DEAR ABBY: I Was Recently Mar- Want to Tell Them Who Did It

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, September 1, 2006 5 Mom in the middle, can not bring daughter and husband together DEAR ABBY: I was recently mar- want to tell them who did it. I really coming a young woman, and sharing transsexual. Your friend needs under- BRENDA IN AUSTIN, TEXAS ried. I have a daughter, “Courtney,” abigail need some advice. — HURTING IN a bed with her father could be too standing, not isolation. DEAR BRENDA: The type of par- from a previous relationship. Things van buren HAYWARD, CALIF. stimulating, for both of them. If he has By all means he should see a psy- ties you have described are more for were great before the wedding. We DEAR HURTING: Pick up the further doubts about this, he should chiatrist — one who specializes in adults than for children. It is more even included Courtney in the plan- phone and call the Rape, Abuse and consult his daughter’s pediatrician. gender disorders. He should have important that your little girl be able ning. Afterward, however, things Incest National Network (RAINN). DEAR ABBY: About a month ago, counseling if he wants to take this to enjoy her birthday with some of dear abby turned sour. • The toll-free number is (800) 656- I was shocked out of my shoes. My where it is heading, and also to cope HER friends than it be a command Courtney kept causing problems 4673. Counselors there will guide you longtime friend, “Orville,” told me he with the loss of his friends. It would performance for your sisters. -

Barry Young Interview Conducted by Randy Rockafellow

SPRING 1998 I ASIFA Central's Sixth Annual Animator's Retreat by Melissa Bouwman Ah Spring, the perfect time of the year to Central Reel. The reel received an gather together with fellow animators in a overwhelmingly positive response from all gorgeous state park in Illinois. This year audience members. A huge thanks went around 20 people jumped at the chance to out to absentee member Jim Schaub who be a part of this annual animator's so graciously took on the task of editing gathering, and a fantastic time was had by the reel together. After Friday's events had A all. concluded, our group split up to enjoy the lodge's many recreational activities Q The sixth annual ASIFA Central Animation including soaking in a hot tub, enjoying U Retreat took place April 3-6 r----------, libation's at the bar, or going F this year, a little earlier than for an evening stroll. A other years, but fortunately "The crowning event R for the attendees, the of Friday evening Saturday morning started off T weather was lovely. was the premier with our key speaker, Kim R_ White, Technical Director at E Basically, the conference is screening of the new R a time for animators to Pixar. Kim discussed how she relax, watch some ASIFA Central Reel." was able to still find time and L animation, and share -Melissa Bouwman resources to still produce her Y information, and that is '--- __.J own art, while maintaining a exactly what our intimate job in the commercial field. P little group did. -

8Th Athens Fashion Week

8th HELLENIC FASHION WEEK VODAFONE ATHENS COLLECTIONS OCTOBER 7-12 2008 - “TECHNOPOLIS”, MUNICIPALITY OF ATHENS, GAZI SHOW SCHEDULE TUESDAY OCTOBER 7, 2008 20:00 CATWALK A ASLANIS 20:00 MAD BARREL CINEMA CELEBRATION-A film about YVES SAINT LAURENT by Olivier Meyrou / FASHION IN CINEMA 21:30 FASHION STAGE OPENING CEREMONY 22:00 ΕΧΗΙΒΙTIONS’ OPENING JANNIS VARELAS-MONT VERTOUX, FASHION WHATEVER, UN/DRESS CODE, TIM & BARRY-UNORTHODOX STYLE WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 8,2008 18:00 CATWALK A VASSILIS ZOULIAS 19:30 CATWALK A YIANNOS XENIS 20:15 FASHION STAGE NIKOS-TAKIS 21:00 CATWALK A DAPHNE VALENTΕ 17:30 CATWALK B FASHION TRENDS PROGNOSIS (ELKEDE) 20:00 MAD BARREL CINEMA MODE IN FRANCE by William Klein, Video Clips 21:30 MAD BARREL THE MAD BARREL CONCERT THURSDAY OCTOBER 9, 2008 19:15 CATWALK A KATERINA KAROUSSOS 20:00 CATWALK B FRIDA KARADIMA 20:45 CATWALK A ELENA STROΝGYLIOTOU 21:30 MAD BARREL KATERINALEXANDRAKI 20:00 MAD BARREL CINEMA MARC JACOBS & LOUIS VUITTON by Loic Prigent, Video Clips 22:00 MAD BARREL THE CALLAS LIPSTICK: MUSIC PERFORMANCE FRIDAY OCTOBER 10, 2008 19:15 CATWALK B DEMNA GVASALIA (FFI) 20:00 CATWALK A MARIA MASTORI-FILEP MOTWARY 21:00 CATWALK B JUUN J. 21:30 MAD BARREL DIMITRIS DASSIOS 20:00 MAD BARREL CINEMA THE NOMI SONG: The Klaus Nomi Odyssey by Andrew Horn 20:30 OPEN AIR SPACE COLLAGE SOCIAL INSTALLATION 22:00 FASHION STAGE STREET FASHION & ARTISTS SATURDAY OCTOBER 11, 2008 17:00 CATWALK A VRETTOS VRETTAKOS 17:45 CATWALK B AFRODITI HERA’ 18:30 CATWALK A YIORGOS ELEFTHERIADES 19:15 CATWALK B ANGELOS BRATIS 20:00 CATWALK A -

Saturday and Sunday Movies

4b The Goodland Star-News / Friday, July 29, 2005 abigail My husband was in another part of feel they are responsible for it and are She goes very far, but hasn’t gone all a clinic where she can not only get Brother-in-laws’ the house and didn’t see or hear his afraid they’ll be punished. the way yet. birth control, but also learn how to van buren brother and our son by the back door. Tell your son that no matter what, Would it be wrong of me to take prevent a sexually transmitted dis- I expressed my concern to my hus- he can always come to you and tell Haley to a birth control clinic and ease that could damage her health actions makes band later, after our son had gone to you anything because you love him have the counselors speak with her and/or fertility. It would be a tremen- •dear abby bed. I told him I was uncomfortable and you’re on his side. Let him know and get her on birth control? The dous kindness. Mom uneasy about the idea of his brother being that if he has any questions about woman she lives with doesn’t seem DEAR ABBY: I have six sisters. DEAR ABBY: My 44-year-old Last week, I came home early alone with our son. My husband dis- anything, you will make the time to to care what the girl does and figures We all share the same mother, but brother-in-law, “Bryce,” still lives at from work. -

Mudtv Manual En-Us.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. PEGI ratings and guidance applicable within PEGI markets only. What is the PEGI System? The PEGI age-rating system protects minors from games unsuitable for their particular age group. PLEASE NOTE it is not a guide to gaming difficulty. Comprising two parts, PEGI allows parents and those purchasing games for children to make an informed choice appropriate to the age of the intended player. -

Voodoo Channel List

voodoo channel list ############################################################################## # English: 450-581 ############################################################################## # CBC HD Bravo USA CBS HF USA Space HD Global TV HD ABC HD USA AMC HD WPIX HD1 A/E USA LMN HD Fox HD USA Spike HD CNBC USA KTLA HD HIFI HD FX HD USA NBC HD CTV HD TNT HD E! HD SYFY HD USA Slice HD CP24 HD HBO HD Showcase HD Encore HD Showtime HD Start Movies HD Super CH 1 HD Super CH 2 HD TLC HD USA History HD USA History HD 2 National Geographic HD1 National Geographic USA Oasis HD Animal Planet HD USA Food Network HD USA HG TV USA Discovery HD USA Oasis Bloomberg HD USA CNN HD USA CNN Aljazeera English HLN Russia Today BBC News BBC 2 Bloomberg TV France 24 English Animal Planet Discovery Channel Discovery History Discovery Science Discovery History CBS Action CBS Drama CBS Reality Comedy Central Fashion TV Film4 Food Network FOX Investigation Discovery Lotus Movies MTV Music NASA TV Nat Geo Wild National Geographic Sky 2 Sky Living HYD Sky Movies Action Sky Movies Comedy Sky Movies Crime & Thriller Sky Movies Drama & Romance Sky Movies Family Sky Movies Premiere Sky Movies Sci-Fi & Horror Sky News Sky One SyFy Travel Channel True Movies 1, 2 UK Gold VH1 ############################################################################## # Sports: 600-643 ############################################################################## # TSN- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ESPN 2 USA NFL Network1 NBA TV Sportnet Ontario1 Sportnet World Sportnet 360 Tennis HD Sportsnet -

Chain Reaction" (PG-13) 1:20, DTV, Radio And, Believe Plicity" (PG-13) 7:10

. ENTERTAINMENT TV TONIGHT/Saturday — See Your Aug. 3 TV Vision for programming details York to Los Angeles. A 7:40 p.m. on DIS (6) 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 1 IiTf i?««TiBcTtBK 1 PiTimk mwxim MID PROGRAM NOTES "Gregory K" — Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Bill Smltrovich. Based on the case of a 12-year- ABC Our Town Special 75497 Movie: "Gregory K" Q 51861 News • Movie: (10:35) "The Lost Boys" 2025652 "Our Town Special" — Featured towns; old boy who sued for the right to leave his KCRG-9 8289045 Tama-Toledo; Charles City; Dubuque; Iowa parents and be adopted. Q A 8 p.m. on Q City. O 7 p.m. on Q CBS Smithsonian Fantastic Journey Touched by an Angel Q 5107 Walker, Texas Ranger Q 8671 News • Cheers (10:35) Married Married M * A • S * H USD SB "Second Noah" — Dreamboat. Bethany 'Touched by an Angel" — Interview With KGAN-2 • 2687 8494519 • Children Children (12:05) and Hannah (Zelda Harris, Ashley Gorrell) an Angel. Monica reveals her Identity to a NBC Atlantis: In Search of a Lost The World's Greatest Magic IIQ17403 News 55107 Saturday Night Uve Q 67213 Tales From the play matchmaker for Shirley (Dlerdre O'Con- cynical tabloid editor (Dinah Manoff); a trans KWWL-7 Continent • 31039 Crypt D nell); Ricky (James Marsden) befriends a plant surgeon (Gerald McRaney) faces operat lonely freshman girt. Q A Q 7 p.m. on 3D ing on a drunken driver, p A Q 8 p.m. on FOX NFL Preseason Football: San Diego Chargers at San Francisco 49ers Q 569590 News 3387942 MAD TV (10:35) Q1051039 Slskel & Ebert Forever Knight KFXA-8 IB ff (SB 33 CB "NFL Preseason Football" — San Diego "The World's Greatest Magic II" — Top IPT-12 Lawrence Welk 68107 |Served? Appearance |Movle: "Another Thin Man" 5354590 |Red Green Red Dwarf Off the Air Chargers at San Francisco 49ers.