A Rapid Assessment of Sediment Sources on the Wensum Above Norwich, with Particular Emphasis on Road Crossings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 FEBRYARY Attlebridge Notesa.Pdf

NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION From 466th Bomb Group Association Beverly Baynes Tomb 2122 Grayson Place Falls Church, VA 22043 January 2018 “Jennie” B-24J784th Bomb Squadron, Revetment 2, Attlebridge Attlebridge Notes is printed solely for members of the 466th Bomb Group Association and associates thereof, for their information and entertainment. All information is amassed by Attlebridge Notes. NTHEew NATIONALOrleans WWII MUSEUM &...welcomed the 8th Air Force Historical Cockpit of B-24 at the WWII Museum Society and the 466th Bomb Group Association in late September 2017. The 466th BGA was well-represented, with five of our Veterans attending: back - Frank Bostwick and Earl Wassom; seated - Elmo Maiden, Perry Kerr and SAVE THE DATE! John Kraeger. Family members and second generation folks joined th in, some for the first time. 44 Annual Read all about it inside! 8th Air Force Historical Society Reunion October 10-14, 2018 Dayton, Ohio Reunion Hotel: Crowne Plaza Dayton ALL links to online hotel reservations and registration will be activated by Monday, February 12, 2018 FDR on the plaza at the WWII Museum Group Photo: 8th AFHS https://www.8thafhs.org/ The President’s Report 466th Bomb Group Board Members, January 2018 2018 has arrived, and the 466th BGA will be busy working with projects here and abroad. All these activities, including this fine publication you’re reading, require funds. In this newsletter there is a President Harold “Bull” Dietz, Veteran request for financial assistance from you to assist our projects. Your support will be greatly appreciated. 30 Variah St. Unit 203 th Frank Youngquist & Barb Copies of the Attlebridge Arsenal are still available. -

Marriott's Way Walking and Cycling Guide

Marriott’s Way Walking and Cycling Guide 1 Introduction The routes in this guide are designed to make the most of the natural Equipment beauty and cultural heritage of Marriott’s Way, which follows two disused Even in dry weather, a good pair of walking boots or shoes is essential for train lines between the medieval city of Norwich and the historic market the longer routes. Some of Marriott’s Way can be muddy so in some areas a town of Aylsham. Funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, they are a great way road bike may not be suitable and appropriate footwear is advised. Norfolk’s to delve deeper into this historically and naturally rich area. A wonderful climate is drier than much of the county but unfortunately we can’t array of habitats await, many of which are protected areas, home to rare guarantee sunshine, so packing a waterproof is always a good idea. If you are wildlife. The railway heritage is not the only history you will come across, as lucky enough to have the weather on your side, don’t forget sun cream and there are a series of churches and old villages to discover. a hat. With loops from one mile to twelve, there’s a distance for everyone here, whether you’ve never walked in the countryside before or you’re a Other considerations seasoned rambler. The landscape is particularly flat, with gradients being kept The walks and cycle loops described in these pages are well signposted to a minimum from when it was a railway, but this does not stop you feeling on the ground and detailed downloadable maps are available for each at like you’ve had a challenge. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

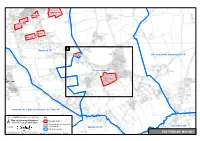

A Frettenham Map

GNLP0190 GNLP0181 GNLP0582 GNLP0512 GNLP0512 A Hainford CP GNLP0065 Horstead with Stanninghall CP Frettenham CP GNLP0492 GNLP0085 Horsham St. Faith and Newton St. Faith CP GREATER NORWICH LOCAL PLAN Key Map set showing Submitted Submitted Sites ± Sites in Frettenham Parish Broads Authority Boundary ( where applicable ) Crostwick CP 1:10,000 Spixworth CP Parish Boundary © Crown Copyright and database right 2016.Ordnance Survey: Broadland District Council - 100022319 Norwich City Council - 100019747 South Norfolk District Council - 100019483 FRETTENHAM MAP SET GP 1.22m RH ED & Ward B dy MILL ROA D 18.6m FB White House Pon ds Pon d Drain Holey well Barn Drain Path (um) Flore nc e Playing Field CH UR C H LA NE Cottage Long Plantation Sta bl e View Cottage Mas ons 15.9m Sta bl e Cottage View Pon d CHURCH ROAD Barn Aca cia Cottage Brac ken Cottage Hall Horstead with Stanninghall CP Grov e Cottage Fa irfi eld 3 Valley Farm Cedar Cottages FRETTENHAM ROAD BUXTON ROAD Pon d The G rang e 1 GP Crown B arn Pon d Rose an d Crown 19.6m 64 (PH ) 50 CR Haw thorn Cottage The Bungalow Rose Cotta ge 2 1 3 48 The Pound Garage Walter 60 Fie ld MILL 11 7 46 Barns FIE LD 40 9 Guide Post COU RT Pon d Mill Fa rm Hainford CP 15.1m 18.1m Lodge Mill View Pon d 54 Grove Farm Drain 1 19.5m Pon d Hainford Place 36 Letter GNLP0065 Box MILL ROA D 34 1 50 The Studio Silos Mill Farm 10 The Willows Pond 42 11 SHIRLEY CLOSE 48 44 6 1.22m RH 6 40 32 Birbeck Way 46 Beulah Cas a M ia Farm 1 16 SCHOOL RO AD Pon d 34 2 27 Thatched Track Cottage Pon d Guide Post RED ME RE CLOSE -

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List Of

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List of 1471412 It 44 Norfolk Census 1851 Index 6115160 Norfolk Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It 1 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1811-1825 375230 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1825-1839 375231 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1839-1859 375232 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1715-1734 1596461 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1734-1749 1596462 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1770-1774 1596563 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1774-1781 1596564 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1790-1797 1596566 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1798-1803 1596567 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1812-1819 1596597 Norfolk Marriages Parish Registers 1539-1812 496683 It 2 Norfolk Probate Inventories Index 1674-1825 1471414 It 17-20 Norfolk Tax Assessments 1692-1806 1471412 It 30-43 Norfolk Wills V.101 1854-1857 167184 Norfolk Alburgh Parish Register Extracts 1538-1715 894712 It 5 Norfolk Alby Parish Records 1600-1812 1526778 It 15 Norfolk Aldeby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 6 Norfolk Alethorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Arminghall Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Ashby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 7 Norfolk Ashby Parish Register Extracts 1646 894712 It 5 Norfolk Ashwell-Thorpe Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Aslacton Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Baconsthorpe Parish Register Extracts 1676-1770 894712 It 6 Norfolk Bagthorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Bale Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Bale Parish Register Extracts 1538-1716 894712 It 6 Norfolk Barmer Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barney Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barton-Bendish Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633. -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Henry High 1 Henry High b: Abt. 1745 . +Elizabeth Fill m: 06 Aug 1764 in Briston .... 2 Benjamin High b: 09 Sep 1764 in Briston d: 12 Nov 1848 in Cley next the Sea ........ +Mary Wilkinson b: 1769 m: 29 Dec 1791 in Booton d: 19 Apr 1829 in Cley next the Sea ........... 3 Benjamin High b: 29 Apr 1792 in Booton d: Abt. Jun 1879 in Walsingham District ............... +Mary Josh b: Abt. 1792 in Mattishall d: Abt. Dec 1880 in Walsingham District .................. 4 Benjamin High b: 03 Feb 1817 in Glandford d: Bef. 1841 .................. 4 Henry High b: 01 Apr 1818 in Glandford d: 05 Nov 1886 in Wood Norton ..................... +Mary Ann Pitcher b: Abt. 1824 in Weybourne m: Abt. Jun 1845 in Walsingham District ........................ 5 Benjamin High b: 07 Sep 1845 in Weybourne d: 28 Jul 1851 in Wiveton ........................ 5 Mary Elizabeth High b: Abt. 1847 in Wiveton ........................ 5 William Henry High b: 10 Sep 1854 in Wiveton Norfolk ............................ +Elizabeth Handley b: Abt. 1858 in Carlton Notts m: Abt. Dec 1876 in Leeds District ............................... 6 Ada Florry High b: Abt. 1878 in Wortley Leeds Yorkshire ................................... +Henry Knaggs b: Abt. 1879 m: Abt. Sep 1907 in Hunslet District ............................... 6 Gertrude Annie High b: Abt. Dec 1884 in Hunslet Leeds ............................... 6 William Martin High b: Abt. Mar 1887 in Hunslet Leeds ............................... 6 Nellie High b: Abt. Sep 1889 in Hunslet Leeds .................. *2nd Wife of Henry High: ..................... +Charlotte Edwards b: Abt. 1857 in Mattishall m: Abt. Sep 1880 in Mitford District ........................ 5 Beatrice High b: Abt. 1878 in Wood Norton ....................... -

River Wensum Restoration Strategy

Appendix 2 Mill summary sheets HELLESDON MILL Table Ba1 Hellesdon Mill Location Mill name: Hellesdon Mill National grid reference: 619800, 310500 Upstream catchment area: 650km2 Length of channel to next mill upstream: 5km Geomorphological Appraisal (2006) reaches: W50 River Wensum Restoration Strategy reach RWRS 01 code: Mill owner: Environment Agency (site only, mill buildings demolished) Sluice owner: Environment Agency Owner of water rights: Environment Agency Listed status: None Plate Ba1 Left: View of one of the fixed weirs at Hellesdon Mill: Right: Hellesdon Mill viewed from downstream 234 Table Ba2 Hellesdon Mill Weir & channel details Water control level: 3.85m AOD Drop: 1.21m (to 2.64m AOD) Length of backwater 5km (100% reach) upstream: Main structure: Block A: 1 flume with a steel control sluice and a horizontal steel penstock plus 3 fixed weirs with stop-log facilities and weed screens; Block B: An automated, bottom hinged overshot tilting gate. Invert 2.52m AOD Operation of main Block A: Permits majority of flow to enter the section below the mill. Sluice only structure: used during high flows in conjunction with Tud sluices; Block B: Controls mean water level upstream in the River Wensum. By-pass structure: Tud sluice acts as bypass channel - see below By-pass structure Automated operation: Gauging station: None Table Ba3 Hellesdon Mill Previous works or recommendations Previous measures: Sluice connecting the River Wensum to the River Tud (about 100m upstream of the main sluices) was automated in 1999. This allows the Environment Agency to accurately maintain water levels upstream of the mill. Geomorphological De-silt reach. -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Election of Parish

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED North Norfolk Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Aldborough and Thurgarton Reason why Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer no longer nominated* BAILLIE The Bays, Chapel Murat Anne M Tony Road, Thurgarton, Norwich, NR11 7NP ELLIOTT Sunholme, The Elliott Ruth Paul Martin Green, Aldborough, NR11 7AA GALLANT Spring Cottage, The Elliott Paul M David Peter Green, Aldborough, NR11 7AA WHEELER 4 Pipits Meadow, Grieves John B Jean Elizabeth Aldborough, NR11 7NW WORDINGHAM Two Oaks, Freeman James H J Peter Thurgarton Road, Aldborough, NR11 7NY *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. The persons above against whose name no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. Dated: Friday 10 April 2015 Sheila Oxtoby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Electoral Services, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9EN STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED North Norfolk Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Antingham Reason why Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer no longer nominated* EVERSON Margra, Southrepps Long Trevor F Graham Fredrick Road, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP JONES The Old Coach Independent Bacon Robert H Graham House, Antingham Hall, Cromer Road, Antingham, N. Walsham, NR28 0NJ LONG The Old Forge, Everson Graham F Trevor Francis Elderton Lane, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NR LOVE Holly Cottage, McLeod Lynn W Steven Paul Antingham Hill, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0NH PARAMOR Field View, Long Trevor F Stuart John Southrepps Road, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. -

Broadland District Local Plan (Inner Area) Norfolk

Broadland District Local Plan (Inner Area) Norfolk AGRICULTURAL LAND CLASSIFICATION AGRICULTURAL LAND CLASSIFICATION BROADUVND DISTRICT LOCAL PLAN (INNER AREA) 1. BACKGROUND 1.1 Broadland District Council have requested Agricultural Land Classification information for three small sites to the north of Norwich (in total 28.5 hectares). Two sites lie adjacent to the A1151 road near Sprowston and the third site lies adjacent to the hospital at Hellesdon. ADAS surveyed the sites in July 1992 to assess the agricultural land quality. Auger boring samples were taken at 100m intervals and the information supplemented by three soil pits. 1.2 On the published Agricultural Land Classification map sheet 126 (Provisional, scale 1:63360, MAFF 1972) the Sprowston areas are shown as grade 3 with a narrow band of urban adjacent to the A1151 road. The Hellesdon area is shown as land primarily in non agricultural use because of its vicinity to the hospital. Since this map is of a reconnaissance nature designed primarily for strategic planning purposes, the current survey was undertaken to provide more detailed information on land quality for the survey area. 1.3 The site lying west of the A1151 road was graded in detail in 1982 and the current work confirms the ALC grading using the MAFF's revised ALC system which was introduced in 1988. 2. PHYSICAL FACTORS AFFECTING LAND QUALITY Climate 2.1 Climate data for the site was obtained frora the published agricultural climatic dataset (Met Office, 1989). This indicates that the annual average rainfall is 626 mm (24.6"). This data also indicates that field capacity days are 121 and moisture deficits are 119 mm for wheat and 114 nun for potatoes. -

THE GLAVEN RIVER CATCHMENT Links Between Geodiversity and Landscape

THE GLAVEN RIVER CATCHMENT Links between geodiversity and landscape - A resource for educational and outreach work - Tim Holt-Wilson Norfolk Geodiversity Partnership CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Landscape Portrait 3.0 Features to visit 4.0 Local Details 5.0 Resources 1.0 INTRODUCTION The River Glaven is partly a chalk river, of which there are more in England than any other country in the world. Chalk rivers are fed from groundwater sources in chalk bedrock, producing clear waters. Many of them have ‘winterbourne’ stretches in their headwaters, with intermittent or absent flow in summer. They have characteristic plant communities, and their gravelly beds, clear waters and rich invertebrate life support important populations of brown trout, salmon and other fish. The Stiffkey is a notable example of a chalk river in north Norfolk, and is classified as one between Edgefield Bridge (TG085363) and Glandford Bridge (TG045415). This report explains the links between geodiversity and the biological and cultural character of the river catchment. It provides a digest of information for education and interpretive outreach about this precious natural resource. Some specialist words are marked in blue and appear in the Glossary (section 5). 2.0 LANDSCAPE PORTRAIT 2.1 Topography and geology The River Glaven is a river in north Norfolk with a length of 17 km (11 miles). Its catchment drains an area of some 115 sq km, with its headwaters in the uplands of the Cromer Ridge. It is fed by several tributaries, including the Thornage Beck and Water Lane Beck, among other spring-fed sources; there are no tributaries in the lower reaches where it flows directly over chalk bedrock.