Adam Somebody's House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 National Western ROV Angus Bull Show AAA Epds As of 1/6/2012; CAA Epds As of 1/9/2012

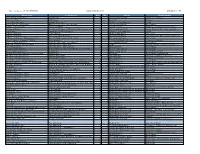

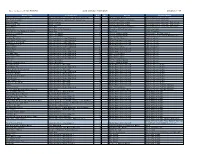

2012 National Western ROV Angus Bull Show AAA EPDs as of 1/6/2012; CAA EPDs as of 1/9/2012 Place Entry Animal Name DOB Reg # Birth Wean Milk Year SC Weight Bulls Class 1B (* Indicates Sale Bulls) _____ 1396 Laflins Storm 1102 6/15/11 17001855 I+1.0 I+52 I+24 I+94 28.0 _______ Sire: SAV Bismarck 5682 .05 .05 .05 .05 Dam: Laflins Primrose 8153 Owner(s): Clinton Laflin, Olsburg, KS _____ 1397 J Bar Angus Black Knight0001 6/10/11 17005577 N/A N/A N/A N/A 32.0 _______ Sire: SAV Brave 8320 Dam: J Bar Angus Georgina 7123 Owner(s): C A Jones, Sunray, TX Class 2B _____ 1398 Fraser Fireman 1195 5/28/11 17003111 +2.4 +57 +16 +87 30.0 _______ Sire: Laflins South Wind 5258 .27 .19 .10 .13 Dam: Fraser Queen Dianna 401 Owner(s): Fraser Livestock, Lincoln, CA _____ 1399 IL Payday 16 5/15/11 16966925 +4.0 +70 +33 +118 31.5 _______ Sire: PVF ALL PAYDAY 729 .34 .27 .16 .22 Dam: Bear Mtn Dolly 4026 Owner(s): Arnold & Teresa Callison, Blackfoot, ID; Robert & Judy Mc Calmant, Layton, UT; Shandar Angus Ranch, Payson, UT _____ 1400 PT Joker 1411 5/15/11 16969690 I+3.5 I+44 I+19 I+79 32.0 _______ Sire: PT Roth Famous Addiction 101 .05 .05 .05 .05 Dam: PT Alibi 1008 Owner(s): Pheasant Trek, Wilton, CA _____ 1401 DAJS Indian Uprising 928 5/12/11 17018692 +3.3 +52 +17 +89 31.0 _______ Sire: Leachman Saugahatchee 3000C .35 .27 .23 .22 Dam: DAJS Electress J928 Owner(s): Doug Satree Angus, Montague, TX _____ 1402 KB Super Duty 1486W 146 5/12/11 17052580 I+3.4 I+58 I+20 I+99 33.0 _______ Sire: Sedgwicks Powerstroke 1486W .05 .05 .05 .05 Dam: 4J Lady VRD Maxine 3610 -

Reflections Poetry Magazine 2021

REFLECTIONS 2021 The Poetry Magazine of Green Brook Middle School 1 2 REFLECTIONS 2021 The Poetry Magazine of Green Brook Middle School Faculty Advisor: Mr. Fornale Special Thanks: Ms. Subervi, Mrs. Casale, all Grade 5 and ELA Teachers, all students who submitted poetry, and all parents who encouraged them. Art Credit: Front Cover, Conrad Kohl 3 4 Grade 5 5 6 Haiku We unite to fight Darkness that is still in sight. So unite, not fight. by Samer Anshasi Minecraft Minecraft is original It is my favorite game Now Minecraft is getting its biggest update Everything In the world is being redone Crazy new features are being added Really crazy monsters are being put in Amazing blocks and biomes are coming too Fun mechanics are also being added Tools that help you build machines are being added by Zachary Anthenelli Video Games Very Interesting Digital Exciting Out of this world Galactic Addicting Monsterous Excellent Super fun games by Julian Apilado 7 Haiku: Monkeys Swinging on a vine Always wanting bananas Monkeys don’t sit still by Eva Arana Swim Team My coach is named Pat He has a twin brother named Matt. He trains us to swim fast So we don’t end up coming in last. We are the Water Wrats! by Callum Benderoth A Weird Day I don’t want to go to school today it ain’t my birthday but I’ll have fun today Or I’ll be castaway So let's go underway by Grayson P. Breen 8 Seasonal Haikus Spring Fall Spring is cold and hot Fall makes leaves fall down Spring has a lot of pollen Fall makes us were thick jackets Spring has cold long winds Fall makes us rake -

Queer Identities and Glee

IDENTITY AND SOLIDARITY IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES: QUEER IDENITIES AND GLEE Katie M. Buckley A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music August 2014 Committee: Katherine Meizel, Advisor Kara Attrep Megan Rancier © 2014 Katie Buckley All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine Meizel, Advisor Glee, a popular FOX television show that began airing in 2009, has continuously pushed the limits of what is acceptable on American television. This musical comedy, focusing on a high school glee club, incorporates numerous stereotypes and real-world teenage struggles. This thesis focuses on the queer characteristics of four female personalities: Santana, Brittany, Coach Beiste, and Coach Sue. I investigate how their musical performances are producing a constructive form of mass media by challenging hegemonic femininity through camp and by producing relatable queer female role models. In addition, I take an ethnographic approach by examining online fan blogs from the host site Tumblr. By reading the blogs as a digital archive and interviewing the bloggers, I show the positive and negative effects of an online community and the impact this show has had on queer girls, allies, and their worldviews. iv This work is dedicated to any queer human being who ever felt alone as a teenager. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my greatest thanks to my teacher and advisor, Dr. Meizel, for all of her support through the writing of this thesis and for always asking the right questions to keep me thinking. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Shooting Star Owl City Piano Music . Shooting Star Video Logo

Full version is >>> HERE <<< For free, stock trading strategy pdf getting free instant access forex mystery - real product 75% commission Download from official url --> http://urlzz.org/forexmys/pdx/17b1p2am-e1c1s30f70j48i315/ Tags: download, how to reveal the forex mystery with candlestick pattern recognizer! - detailed info- forex profit system 1.1, reveal the forex mystery with candlestick pattern recognizer!, for free, stock trading strategy pdf getting free instant access forex mystery - real product 75% commission. shooting star dragon card price morning star soy sausage patties nutrition evening star costa rica candlestick patterns tutorial pdf high profit candlestick patterns book shooting star bad company song meaning shooting star drive in reviews shooting star dragon tin list morning star 879 9th ave best price action trading system morning star school of nursing pattern recognizer indicator pattern recognizer java oil trading system review gucci mane shooting star download morning star christian school haiti shooting star video download morning star ratings morning star bamboo stair treads morning star baptist church burrowsville va morning star stables sims 3 metastock trading system download 1 min forex strategy tennis trading strategy + betfair forex king kong trading system download rovernorth forex system download morning star sausage price and volume trading system shooting star dragon deck 2011 eldest 11 the morning star download shooting star owl city piano sheet directional trading strategy definition shooting star -

Thursday, December 20, 2007

REGULAR JUNE JUNE 19, 2008 THURSDAY, JUNE 19, 2008 NINE THIRTY A.M. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA STATE OF ILLINOIS COUNTY OF WILL Executive Walsh called the meeting to order. Member Babich led in the Pledge of Allegiance to our Flag. Member Babich introduced Pastor Lishers Mahone, Jr. of Brown Chapel AME, who delivered the invocation. Roll call showed the following Board members present: McMillan, Woods, Anderson, Piccolin, Singer, Brandolino, Weigel, Dralle, Riley, Wisniewski, Kusta, Maher, Blackburn, Gerl, Goodson, Baltz, Gould, Rozak, Bilotta, Konicki, Svara, Stewart, Travis, Adamic, Babich, Wilhelmi, Moustis. Total: Twenty-seven. Absent: None. THE EXECUTIVE DECLARED A QUORUM PRESENT. Member Wisniewski made a motion, seconded by Member Babich, the Certificate of Publication be placed on file. Voting Affirmative were: McMillan, Woods, Anderson, Piccolin, Singer, Brandolino, Weigel, Dralle, Riley, Wisniewski, Kusta, Maher, Blackburn, Gerl, Goodson, Baltz, Gould, Rozak, Bilotta, Konicki, Svara, Stewart, Travis, Adamic, Babich, Wilhelmi, Moustis. Total: Twenty-seven. No negative votes. THE CERTIFICATE OF PUBLICATION IS PLACED ON FILE. Member Singer made a motion, seconded by Member Gerl, to approve the May 15, 2008 County Board Minutes. Voting Affirmative were: McMillan, Woods, Anderson, Piccolin, Singer, Brandolino, Weigel, Dralle, Riley, Wisniewski, Kusta, Maher, Blackburn, Gerl, Goodson, Baltz, Gould, Rozak, Bilotta, Konicki, Svara, Stewart, Travis, Adamic, Babich, Wilhelmi, Moustis. Total: Twenty-seven. No negative votes. 538 REGULAR JUNE JUNE 19, 2008 THE MINUTES FOR THE MAY 15, 2008 COUNTY BOARD MEETING ARE APPROVED. Elected officials present were: Auditor, Steve Weber; Circuit Clerk, Pam McGuire; County Clerk, Nancy Schultz Voots; County Executive, Larry Walsh; Recorder of Deeds, Laurie McPhillips; Sheriff, Paul Kaupas; State’s Attorney, James Glasgow; and Superintendent Jennifer-Bertino Tarrant. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Music Express Song Index V1-V17

John Jacobson's MUSIC EXPRESS Song Index by Title Volumes 1-17 Song Title Contributor Vol. No. Series Theme/Style 1812 Overture (Finale) Tchaikovsky 15 6 Luigi's Listening Lab Listening, Classical 5 Browns, The Brad Shank 6 4 Spotlight Musician A la Puerta del Cielo Spanish Folk Song 7 3 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A la Rueda de San Miguel Mexican Folk Song, John Higgins 1 6 Corner of the World World Music A Night to Remember Cristi Cary Miller 7 2 Sound Stories Listening, Classroom Instruments A Pares y Nones Traditional Mexican Children's Singing Game, arr. 17 6 Let the Games Begin Game, Mexican Folk Song, Spanish A Qua Qua Jerusalem Children's Game 11 6 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A-Tisket A-Tasket Rollo Dilworth 16 6 Music of Our Roots Folk Songs A-Tisket, A-Tasket Folk Song, Tom Anderson 6 4 BoomWhack Attack Boomwhackers, Folk Songs, Classroom A-Tisket, A-Tasket / A Basketful of Fun Mary Donnelly, George L.O. Strid 11 1 Folk Song Partners Folk Songs Aaron Copland, Chapter 1, IWMA John Jacobson 8 1 I Write the Music in America Composer, Classical Ach, du Lieber Augustin Austrian Folk Song, John Higgins 7 2 It's a Musical World! World Music Add and Subtract, That's a Fact! John Jacobson, Janet Day 8 5 K24U Primary Grades, Cross-Curricular Adios Muchachos John Jacobson, John Higgins 13 1 Musical Planet World Music Aeyaya balano sakkad M.B. Srinivasan. Smt. Chandra B, John Higgins 1 2 Corner of the World World Music Africa: Music and More! Brad Shank 4 4 Music of Our World World Music, Article African Ancestors: Instruments from Latin Brad Shank 3 4 Spotlight World Music, Instruments Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 8 4 Listening Map Listening, Classical, Composer Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 1 4 Listening Map Listening, Composer Ah! Si Mon Moine Voulait Danser! French-Canadian Folk Song, John Jacobson, John 13 3 Musical Planet World Music Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around African-American Folk Song, arr. -

Therapies Families Share the Importance of This Vital Service Shine Winter 2019 Welcome to Shine a Message from Highlights Inside

Shine Winter 2019 magazine New superb sensory walkway Our volunteer survey results Ted and Dylan-James’ stories Therapies Families share the importance of this vital service Shine Winter 2019 Welcome to Shine A message from Highlights inside Our welcome for this edition of Shine is from News Kim, one of our incredible volunteers. She 3 New sensory walkway has volunteered for Shooting Star Children’s 4 George’s Dragons year Hospices for three years. of fundraising 10 Volunteer survey results “I saw an advert for an Open Day at Shooting Star House in Hampton whilst I was unable to Family stories work and went along to find out more about my local children’s hospice. It was incredible 6 Ted’s story to see first-hand the work that went on inside, 12 Dylan-James’ story so I decided to sign up as a volunteer. I mostly volunteer on reception at the charity’s office in Weybridge, covering various reception shifts each week. Feature I’m also a Legacy Ambassador, which involves talking to potential supporters 8 Supporting families about leaving a gift in their will – many people don’t realise that leaving a with therapies legacy to a charity is actually quite simple so I enjoy telling supporters about the process and the difference it makes. Your Shooting Star Children’s Hospices “It’s always a pleasure to read the family stories in Shine and the stories in 11 A day in the life of a... this edition are no different – they really bring home just how vital Shooting Hospice at Home Nurse Star Children’s Hospices is. -

PDF (V. 66:30, May 27, 1965)

Support Take Lt. Newton Your Local Home for Lunch Police CalifomiaTech Associated Students of the California Institute of Technology Volume LXVI. Pasadena, California, Thursday, May 27, 1965 Number 30 Snake, VR, andTBP Frosh Awards Given at Assembly Honor and athletic awards were GPA. John Tucker then an ability, and individual improve presented at the Spring Awards nounced Greg Kourilsky as Tau ment. The frosh John C. Peter Assembly yesterday evening in Beta Pi Frosh of the Year. son Baseball Trophy was granted Tournament Park. Fleming swept The Caltech Outstanding Ath by Coach Jensen to Edward away the big metal by taking the lete award was presented by Mr. Chapyak, this year's team captain Snake, Interhouse Rating, and Emery to two Techmen - Wal who was voted most valuable Discobolus Trophies. Ruddock ter Innes and John Frazzini. The player by his teammates. copped the Varsity Rating Tro co-winners were selected by the Walter Innes, winner of the phy. The two-hour program fea Athletic Department staff. The Soccer Trophy, was named by tured Dr. William Corcoran as award is given to those athletes Mr. Emery as the most outstand emcee. making the greatest contributions ing player. The honor keys and certificates to Caltech intercollegiate sports Finally, Mr. Musselman pre were presented by Fred Brun in terms of ability, leadership, sented the Varsity Rating Tro swig, ASCIT President. Nelit Dr. loyalty, and interest. phy, based on the relative num Eagelson awarded the Golds Outstanding athletes ber of House members contribut worthy Interhouse S c hoI a s t ic Coach Preisler gave the Vesper ing to varsity and frosh teams, Achievement (Snake) Trophy to Basketball Trophy to a varsity to Ruddock. -

Music Express Song Index V1-V17

John Jacobson's MUSIC EXPRESS Song Index by Theme/Style Volumes 1-17 Song Title Contributor Vol. No. Series Theme/Style I've Got Peace Like a River African-American Spiritual, arr. Rollo Dilworth 15 1 Music of Our Roots African-American Spiritual Who Built the Ark? African-American Spritual, arr. Janet Day 15 4 Recorder Heroes & Sidekicks African-American Spiritual Over My Head Emily Crocker 16 1 Read & Sing Folk Songs African-American Spiritual, Folk Songs Angel Band, The Emily Crocker 16 3 Read & Sing Folk Songs African-American Spiritual, Folk Songs Good News Janet Day 16 4 Recorder Heroes & Sidekicks African-American Spiritual, Recorder, Pentatonix Janet Day, John Jacobson 17 1 One2One Video Interview Artist interview Aly & AJ, Do You Believe in Magic Janet Day 6 1 Spotlight Artist, Musician Signs and Symbols Cristi Cary Miller 17 5 Let the Games Begin Assessment, Review, Game Melody Hunt Cristi Cary Miller 17 4 Let the Games Begin Aural recognition, Game, Assessment, We Are Marching John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 7 2 Hop 'Til You Drop Back to School Right Here! Right Now! John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 8 1 Music Express in Concert Back to School Children of the World John Jacobson, Rollo Dilworth 9 1 Music Express in Concert Back to School New Beginning, A John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 9 4 Music Express in Concert Back to School Walk Faster! John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 10 5 Hop 'Til You Drop Back to School Planet Rock John Jacobson, Mac Huff 11 1 Music Express in Concert Back to School Let's Go! John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 12 1 Music -

On Collazo Indictment Grand Jury Actslnspiress,A,E Ln Capi,°Lc,Assic

A Newspaper With A Constructive PER COPY VOLUME 19, NUMBER 42 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 1950 PRICE FIVE CENTS Grand Jury Actslnspires s,a,e ln Capi,°l C,assic 24th DIVISION FIGHTS Says Robeson • .<■ r On Collazo WITH BRITISH BRIGADE Will Sue lhe Idi BY IRVING R. LEVINE Indictment International News Service War Correspondent Slate Dept. SEOUL, Korea - (Sunday) - Full might of United Nations WASHINGTON. DC A Fed forces was hurled by General Douglas MacArthur today against eral Grand Jury acted wi|h utipre- ■ WASHINGTON -<ANP1- Paul I an estimated 110,000 communist troops in a gigantic blow io Robeson, noted American singer, cedented speed Friday to indict has revealed his plans to file suit Oscar Collazo for fir-t degree mur win victory before more Chinese reinforcements teach enemy agaijist the Department of State der and felonious assault in the lines in North Korea for declaring his passport "null end November 1 attempt to assassinate American and British -pc.iiiie.ui. Yalu River border ol Maii.hui a void" after he refused to return it President Truman. .«truck inauiCoiiimunbl luu i.i trie One euch y jet plme »a h>i at the department's request a fev Northwest sector about til mile down in Haine- ami two otlr: The District of Columbia Jury re montlis ago turned two murder count, against j mirth of the Chongch'in river ami were listed as "appwntly Ir tmy- If hr Is succe»ltil in having it (he Puerto Rican Nationalist in con 60 milts below the Mam-huriaii tot- cd " validated, he claims that he wtll be nection with (lie «laying of White able to fulfill his worldwide sing In Northeast orca, American .nil House Guard Leslie Coffelt during S 24th Inf.mUv Division an.I ing engagements which have been SAutFi Korean units continued Hi ' i 1 a wild shooting melee in front of British coiiimonwnltli brig arranged to include performances in the President's Blair House resi troops hammered out gains . -

BTS-Somerset-September-Program

Competition Event Schedule SOMERSET, NJ SEPTEMBER 2019-2020 September 25-27, 2020 Friday - September 25, 2020 All Star Solo Lyrical - Ages: 10-12 4:00 PM 1 I Can't Breathe Julia Smith All Star Solo Musical Theater - Ages: 13-15 4:03 PM 2 River Deep Mountain High Sami Reiser All Star Solo Tap - Ages: 7-9 4:06 PM 3 Blue Suede Shoes Addison Fodor Shooting Star Duo/Trio Tap - Ages: 10-12 4:09 PM 4 War Gabriella De Palma, Gianna Nelson, Ava Zodda Shooting Star Small Group Hip Hop - Ages: 7-9 4:13 PM 5 For My People Sabrina Antonucci, Evelyn Chichester, Daniela Loving, Gillian Mitchell, Lilly Mitreski, Alura Realmonte, Camryn Scarlett All Star Solo Jazz - Ages: 10-12 4:16 PM 6 Everlasting Love Giuliana Czerniawski All Star Solo Open - Ages: 10-12 4:19 PM 7 Piano Man Julia Smith Rising Star Solo Contemporary - Ages: 13-15 4:22 PM 8 Painted Black Claudia Dasilva Rising Star Solo Contemporary - Ages: 16-20 4:26 PM 9 Train Wreck Emma Wohl Rising Star Solo Jazz - Ages: 7-9 4:29 PM 10 Butterfly Evangeline Spina Rising Star Solo Contemporary - Ages: 13-15 4:32 PM 11 Love Is Julianna Zelnhefer All Star Solo Contemporary - Ages: 13-15 4:35 PM 12 Sinking Grace Dangelo 13 54321 Dea Mullaj Rising Star Solo Tap - Ages: 13-15 4:42 PM 14 Waving Through A Window Melanie Gilbert All Star Duo/Trio Jazz - Ages: 10-12 4:45 PM 15 That's Not My Name Giuliana Czerniawski, Kaylin Kavanagh, Abby Kearns All Star Solo Jazz - Ages: 13-15 4:49 PM 16 Thumbs Leilani Doyley All Star Duo/Trio Hip Hop - Ages: 10-12 4:52 PM 17 2Legit Cassandra Gariepy, Olivia Shaffer Rising