James Thurber: a Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

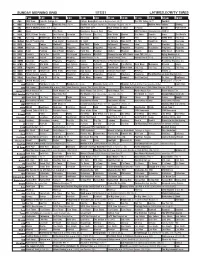

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Iowa at Northwestern. (N) Å The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Washington Capitals at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Å Mecum Auto Auctions Skating 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Emeril Pain Relief! 7 ABC News This Week Eyewitness News at 9am News AKC National Championship 2020 Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest Sex Abuse Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Paid Prog. MAXX Oven Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse AAA PiYo Paid Prog. MAXX Oven Paid Prog. 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch On Camera Rare 1899 Dr. Ho’s Caught on News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Smile Copper Workout! AAA New YOU! Smile Bathroom? Cleanse Ideal AAA Prostate Paid Prog. 2 2 KWHY Más Pelo Programa Resultados Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Resultados Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Lidia Milk Street Field Trip 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 3 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Amazing Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

The George Washington University Presidential Invitational Tournament February 6, 1994 Semifinal Round the Toss-Ups

The George Washington University Presidential Invitational Tournament February 6, 1994 Semifinal Round The Toss-Ups 1) His first head coaching experience before the NFL was at a high school in Reno, Nevada, a few years after graduating from Stanford. After winning just nine games in three years, he went back to Stanford, where he became a top-notch assistant coach. He moved to the NFL soon afterward as a running-backs coach. He turned down a slot at the GW Law School to become a head coach for the New York Giants, going 14-18 in his two-year stint. FIP, name this man, whom Dan Reeves replaced. Ray Handley 2) Born in 1934, this author served in the Strategic Air Command for four years before studying German and philosophy at Columbia. His first collection of poems, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, reflected the romanticism of the Greenwich Village crowd of his time, but he soon afterward rejected this view for militant Afro-Americanism, as seen in his later plays such as Dutchman and The Slave. FTP, identify this author, who in 1965 chose for himself the name Amiri Baraka. Leroi~ 3) Graham Vivian was an English painter known for his landscapes with arbitrary colors who did famous portraits of Somerset Maugham and Winston Churchill. George was a conservative Supreme Court Justice nominated in 1922 by Warren Harding. Donald is an actor whose credits include M*A*S*H, Animal House, The Firm, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers. FrP, what last name do these three people share? Sutherland 4) Shirts bearing his likeness on front and a line from Apocalypse Now, "Charlie Don't Surf," on back, are now very popular. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

James Thurber and the Midwest

James Thurber and the Midwest Stephen L. Tanner Because of his large role in shaping the tone and character of The New Yorker, a magazine synonymous with urban sophistication, James Thurber is sometimes viewed as an Eastern cosmopolite. This impression is misleading, for although he lived half his life in the East and New York City was the site of his literary success, he remained a partially unreconstructed Midwesterner. His journey from Columbus, Ohio, to New York City was one more example of the familiar pattern of the young man from the provinces who finds the metropolis a catalyst for his genius. But unlike the usual provincial once-removed, he was unashamed of his Midwestern roots and trailed Ohio with him. Among his New York friends he often told stories about his eccentric relatives and acquaintances in Columbus, impersonating the various characters. And of course some of his finest writing treats this same subject. In a 1953 speech accepting a special Ohio Sesquicenten- nial Career medal, he said, "It is a great moment for an Ohio writer living far from home when he realizes that he has not been forgotten by the state he can't forget," and added that his books "prove that I am never very far away from Ohio in my thoughts, and that the clocks that strike in my dreams are often the clocks of Columbus."1 In 1959, when Columbus was named an "All-American City," he wrote to the mayor, "I have always waved banners and blown horns for Good Old Columbus Town, in America as well as abroad, and such readers as I have collected through the years are all aware of where I was born and brought up, and they know that half of my books could not have been written if it had not been for the city of my birth."2 But if it is a mistake to view Thurber as an Eastern sophisticate, it is equally a mistake to infer from these glowing statements about Columbus that he 0O26-3O79/92/33O2-O61$1.5O/0 61 &^*4fc Jp*9 James Thurber, Courtesy of The Ohio State University Library. -

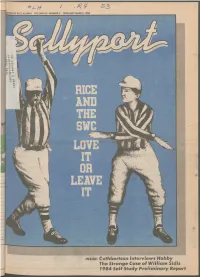

Rice and the Swc

TION OF RICE ALUMNI VOLUME 40, NUMBER 3 FEBRUARY—MARCH 1984 RICE AND THE SWC ngui lowi INSIDE: Cuthbertson Interviews Hobby The Strange Case of William Sidis 1984 Self Study Preliminary Report FEB.-MAR. 1984, VOL. 40/6 Full-Time Hobby BY GILBERT M. CUTHBERTSON 4 Popular Rice political science pro essor Gilbert "Doc C" Cuthbertson interviews Texas Lieuten- EDITOR ant Governor William P HobbV, Jr. '53 about Rice, Austin, and what the future may hold. Virginia Hines '78 SCIENCE EDITOR The Strange Case of William Sidis 6 B.C. Robison Billed as the "world's youngest professor" when he came to study and teach at Rice in 1915, DESIGN "boy wonder" Sidis died 30 years later in obscurity. Now, as several books by or about Sidis are Carol Edwards about to make a belated appearance, his contributions are finally being reevaluated. PHOTOGRAPHER Pam Morris BY LINDA PHILLIPS DRISKILL '61 STUDENT ASSISTANTS On Being Rice . 8 Grace Marie Brown '84 Every ten years, virFien committees of administration, faculty, staff, students, and alumni sit Joan Hope '84 down to evaluate the university, feedback from the greater Rice community is vital. Here we offer preliminary conclusions and encourage readers to let committee chairmen know how OFFICERS OF THE ASSOCIATION OF RICE ALUMNI they feel about the state of the university in 1984. President, Joseph F. Reilly, Jr. '48 President-Elect, Harvin C. Moore, Love It or Leave It 10 1st Vice-President, Carl Morris '76 etbc Once again the old question is raging: should Rice throw in the towel in the Southwest Confer- 2nd Vice-President, Carolyn Devi ccahuoslae ence? In this issue professors James Castarieda and Harold Rorschach spell out the pros and Treasurer, Jack Williams '34 in his cons of keeping a Division I football team in Rice Stadium. -

An Interview with Fred Hellerman Part II May 26, 2016 in This Interview Fred Is Joined by His Wife, Susan Lardner. Ken Edgar

An Interview with Fred Hellerman Part II May 26, 2016 In this interview Fred is joined by his wife, Susan Lardner. Ken Edgar: We are now back in Fred Hellerman's living room and we're continuing our conversation with Fred. We are joined today by Susan Lardner, Fred’s wife, who herself has a very interesting background and career. Together they are going to help us remember their lives in Weston, starting in around 1970. Susan, welcome to the show. When we last left our story we had talked about your arrival in Weston and how Harold Leventhal, the Weaver's manager, had purchased a home near Cobb's Mill and was influential in bringing you up here. As a result, you became interested in Weston and eventually bought the house in which we are sitting today. Susan: I checked with one of Harold's daughters and found out that he had bought his house in 1968 and Fred bought this house in 1969. Although Fred had been up here before visiting other people, he had not been in the house purchasing business. Fred Hellerman: Yeah, coming up there for a weekend. I just fell in love with that immediately. It was a very important place for me. Ken: In the summer of 1970, you two were married right here on this property. Fred: From here, yeah, at this house. Susan: Under the tree, by Euclid Shook. [A Weston artist a justice of the peace. –ed.] Ken: The New York Times did a very interesting description of your wedding. -

Acceleration and Enrichment: Drawing the Base Lines for Further Study

1 ACCELERATION AND ENRICHMENT: DRAWING THE BASELINES FOR FURTHER STUDY Sanford J. Cohn THE CONTROVERSY IN PERSPECTIVE For nearly forty years prior to 1970, the acceleration versus enrichment argument lay dormant as far as the public was concerned. The Great Depression had eliminated the prerogative for public-interested disagreement for all but a few educational and psychological investigators. Before that time, however, there had been proponents of educational acceleration and others who favored enrich- ment. Each group considered its own a singularly appropriate underlying strategy for educating intellectually gifted youngsters. But with few jobs waiting for graduates after 1929, there seemed to be no reason or purpose even for brilliant students to finish their formal schooling. In the ensuing absence of public debate, the unrivaled assumptions implied, and even voiced, by advocates for enrich- ment became entrenched firmly in the nation’s public consciousness. Some of these assumptions were clear expressions of the mythology that had developed in regard to great intellectual talent and precocity. ‘‘Early ripe, early rot’’ was but one epigram that encouraged educators of the mid-1900s to suppress actively the rapid intellectual development experienced by some youths. Parents of such children were counseled to avoid even considering accelerative educational plans for their children. The price one ‘‘surely’’ would have to pay for moving more rapidly through the educational lock step than did one’s age mates washis or her ‘‘social and emotional adjustment.’’ Counselors predicted lives characterized by loneliness and despair for these children if they chose to skip a grade in school or even to move ahead more quickly in certain subjects. -

The Jewels of Aptor, by Samuel R

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Jewels of Aptor, by Samuel R. Delany This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Jewels of Aptor Author: Samuel R. Delany Release Date: February 3, 2013 [EBook #41981] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE JEWELS OF APTOR *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net THE JEWELS OF APTOR by SAMUEL R. DELANY ACE BOOKS, INC. 1120 Avenue of the Americas New York 36, N.Y. THE JEWELS OF APTOR Copyright ©, 1962, by Ace Books, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed in U.S.A. The waves flung up against the purple glow of double sleeplessness. Along the piers the ships return; but sailing I would go through double rings of fire, double fears. So therefore let your bright vaults heave the night about with ropes of wind and points of light, and say, as all the rolling stars go, "I have stood my feet on rock and seen the sky." —These are the opening lines from The Galactica, by the one-armed poet Geo, the epic of the conflicts of Leptar and Aptor. PROLOGUE Afterwards, she was taken down to the sea. She didn't feel too well, so she sat on a rock down where the sand was wet and scrunched her bare toes in and out of the cool surface. -

Congressionali RECORD-SENATE. JANUARY 19

' 1660. CONGRESSIONAli RECORD-SENATE. JANUARY 19,_. the passage of the so-called Pem·ose-Griffin bill • to the Com- SENATE. mittee on the Post Office and Post Roads-. ' · Also, petitiQn of Local Union No. 325, Ogden Utah of the FRIDAY, Janua1'.V 19, 1917. I, International Union of the· United Brewery Workmen' against all prohibitory legislation ; to the Committee on the J~diciary. Rabbi Leo M. Franklin, of Detr~it, Mich., offered the follow Also, memorial of Theatrical Stage Employees' Union of Salt ing prllyer : Lake City, against House bill 18986 and Senate blll 4429 and Almighty God, in whose hands are the destinies of men and similar exclusion legislation ; to the Committee on the Post natiollS, earnestly do we seek Thee in this hour. As i)l the Office and Post Roads. ages past Thou hast guided men through storm and stress to Also, memorial of Local Union No. 30, Brotherhood of Rail s~ety and peace ; as in all times Thy love has lifted and in way Mail Clerks, in favor of increased compensation for postal spired the hearts of men to deeds of heroism and of self-forget employees ; to the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads. ti~g sacrifice, so in these times, 0 Father, do Thou bless us Also, petition of Local Union No. 64 of the International With the light of Thine on-leading love, so that there may be in Unio~ of the United Brewery Workmen, Salt Lake City, against kindled our hearts the fires of loyalty to all that lifts life to all prohibition laws; to the Committee on the Judiciary. -

The International Swimming Hall of Fame's TIMELINE Of

T he In tte rn a t iio n all S wiim m i n g H allll o f F am e ’’s T IM E LI N E of Wo m e n ’’s Sw iim m i n g H i s t o r y 510 B.C. - Cloelia, a Roman maid, held hostage with 9 other Roman women by the Etruscans, leads a daring escape from the enemy camp and swims to safety across the Tiber River. She is the most famous female swimmer of Roman legend. 216 A.D. - The Baths of Caracalla, regarded as the greatest architectural and engineering feat of the Roman Empire and the largest bathing/swimming complex ever built opens. Swimming in the public bath houses was as much a part of Roman life as drinking wine. At first, bathing was segregated by gender, with no mixed male and female bathing, but by the mid second century, men and women bathed together in the nude, which lead to the baths becoming notorious for sexual activities. 600 A.D. - With the gothic conquest of Rome and the destruction of the Aquaducts that supplied water to the public baths, the baths close. Soon bathing and nudity are associated with paganism and be- come regarded as sinful activities by the Roman Church. 1200’s - Thinking it might be a useful skill, European sailors relearn to swim and when they do it, it is in the nude. Women, as the gatekeepers of public morality don’t swim because they have no acceptable swimming garments. -

Oongression Al~ Record-Sen Ate

1899. OONGRESSION AL~ RECORD-SENATE. 1443 By Mr. RAY of New York: Petition of citizens of the Twenty women of Hawaii; which was referred to the Select Committee si:xth Congressi onal district of the State of New York, for the abo on \Voman Suffrage. lition of the sale of liquors in Government buildings, etc.-to the He also presented a memorial of the executive board of the Na Committee on Alcoholic Liquor Traffic. tional Live Stock Exchange, r emonstrating against the unjust By Mr. ROBINSON of Indiana: Petition of citizens of Steuben statements reported to be made by officials high in authority rela County, Ind., to prohibit the sale of liquor in canteens and in im tive to the live-stock industry; which was referred to the Commit migrant stations and Government buildings-to the Committee tee on Agriculture and Forestry. on Alcoholic Liquor Traffic. Mr. HOAR presented the memorial of Charles Franqis Adams, Dy Mr. SHOW ALTER: Petition of Winfield Grange, No. 1105, of Boston, Mass., and 22 other prominent citizens of the United of Butler County, Pa., urging the passage of the Hanna-Payne States, remonstrating against the ratification of the treaty of ~hipping bill-to tho Committee on the Merchant Marine and peace without amendment; which was referred to the Committee Fisheries. on Foreign Relations. Also, petition of the United Presbyterian congregation of Rocky He also presented the memorials of F. J. Kinney and 61 other Springs, Pa., to prohibit the sale of liquor in canteens, in immi citizens, and of Herbert F. Binney and 9 other citizens, all in the grant stations, and in Government buildings-to the Committee State of Massachusetts; of R. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12.