Classic Commonwealth: Virginia Architecture from the Colonial Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lambertville Design Guidelines

Lambertville Design Guidelines September 2, 2009 Draft Lambertville Design Guidelines City of Lambertville Hunterdon County, NJ September 2, 2009 Lambertville City Council Prepared by Mosaic Planning and Design, LLC Hon. David M. DelVecchio, Mayor Linda Weber, PP, AICP Steven M. Stegman, Council President Beth Asaro Ronald Pittore With Assistance From Clarke Caton Hintz Wardell Sanders Geoffrey Vaughn, ASLA Lambertville Planning Board Brent Krasner, PP, AICP Timothy Korzun, Chairman This plan was funded by a generous grant from the Paul Kuhl, Vice-Chairman Office of Smart Growth in the Department of Com- Acknowledgements Hon. David M. Delvecchio, Mayor munity Affairs. Hon. Ronald Pittore, Councilman Paul A. Cronce Beth Ann Gardiner Jackie Middleton John Miller Emily Goldman Derek Roseman, alternate David Morgan, alternate Crystal Lawton, Board Secretary William Shurts, Board Attorney Robert Clerico, PE, Board Engineer Linda B. Weber, AICP/PP, Board Planner Lambertville Historic Commission John Henchek, Chairman James Amon Richard Freedman Stewart Palilonis Sara Scully Lou Toboz 1. Introduction .......................................................................................1 5.3 Street Corridor Design ......................................................17 5.3.1 Sidewalks & Curbs ...................................................................17 2. Overview of Lambertville .............................................................3 5.3.2 Street Crossings ........................................................................17 -

Brief History of Architecture in N.C. Courthouses

MONUMENTS TO DEMOCRACY Architecture Styles in North Carolina Courthouses By Ava Barlow The judicial system, as one of three branches of government, is one of the main foundations of democracy. North Carolina’s earliest courthouses, none of which survived, were simple, small, frame or log structures. Ancillary buildings, such as a jail, clerk’s offi ce, and sheriff’s offi ce were built around them. As our nation developed, however, leaders gave careful consideration to the structures that would house important institutions – how they were to be designed and built, what symbols were to be used, and what building materials were to be used. Over time, fashion and design trends have changed, but ideals have remained. To refl ect those ideals, certain styles, symbols, and motifs have appeared and reappeared in the architecture of our government buildings, especially courthouses. This article attempts to explain the history behind the making of these landmarks in communities around the state. Georgian Federal Greek Revival Victorian Neo-Classical Pre – Independence 1780s – 1820 1820s – 1860s 1870s – 1905 Revival 1880s – 1930 Colonial Revival Art Deco Modernist Eco-Sustainable 1930 - 1950 1920 – 1950 1950s – 2000 2000 – present he development of architectural styles in North Carolina leaders and merchants would seek to have their towns chosen as a courthouses and our nation’s public buildings in general county seat to increase the prosperity, commerce, and recognition, and Trefl ects the development of our culture and history. The trends would sometimes donate money or land to build the courthouse. in architecture refl ect trends in art and the statements those trends make about us as a people. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Executive Order 13967

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Executive Order 13967—Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture December 18, 2020 By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Purpose. Societies have long recognized the importance of beautiful public architecture. Ancient Greek and Roman public buildings were designed to be sturdy and useful, and also to beautify public spaces and inspire civic pride. Throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, public architecture continued to serve these purposes. The 1309 constitution of the City of Siena required that "[w]hoever rules the City must have the beauty of the City as his foremost preoccupation . because it must provide pride, honor, wealth, and growth to the Sienese citizens, as well as pleasure and happiness to visitors from abroad." Three centuries later, the great British Architect Sir Christopher Wren declared that "public buildings [are] the ornament of a country. [Architecture] establishes a Nation, draws people and commerce, makes the people love their native country . Architecture aims at eternity[.]" Notable Founding Fathers agreed with these assessments and attached great importance to Federal civic architecture. They wanted America's public buildings to inspire the American people and encourage civic virtue. President George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson consciously modeled the most important buildings in Washington, D.C., on the classical architecture of ancient Athens and Rome. They sought to use classical architecture to visually connect our contemporary Republic with the antecedents of democracy in classical antiquity, reminding citizens not only of their rights but also their responsibilities in maintaining and perpetuating its institutions. -

Georgetown's Historic Houses

VITUAL FIELD TRIPS – GEORGETOWN’S HISTORIC HOUSES Log Cabin This log cabin looks rather small and primitive to us today. But at the time it was built, it was really quite an advance for the gold‐seekers living in the area. The very first prospectors who arrived in the Georgetown region lived in tents. Then they built lean‐tos. Because of the Rocky Mountain's often harsh winters, the miners soon began to build cabins such as this one to protect themselves from the weather. Log cabin in Georgetown Photo: N/A More About This Topic Log cabins were a real advance for the miners. Still, few have survived into the 20th century. This cabin, which is on the banks of Clear Creek, is an exception. This cabin actually has several refinements. These include a second‐story, glass windows, and interior trim. Perhaps these things were the reasons this cabin has survived. It is not known exactly when the cabin was built. But clues suggest it was built before 1870. Historic Georgetown is now restoring the cabin. The Tucker‐Rutherford House James and Albert Tucker were brothers. They ran a grocery and mercantile business in Georgetown. It appears that they built this house in the 1870s or 1880s. Rather than living the house themselves, they rented it to miners and mill workers. Such workers usually moved more often than more well‐to‐do people. They also often rented the places where they lived. When this house was built, it had only two rooms. Another room was added in the 1890s. -

Chetham Miscellanies

942.7201 M. L. C42r V.19 1390748 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00728 8746 REMAINS HISTORICAL k LITERARY NOTICE. The Council of the Chetham Society have deemed it advisable to issue as a separate Volume this portion of Bishop Gastrell's Notitia Cestriensis. The Editor's notice of the Bishop will be added in the concluding part of the work, now in the Press. M.DCCC.XLIX. REMAINS HISTORICAL & LITERARY CONNECTED WITH THE PALATINE COUNTIES OF LANCASTER AND CHESTER PUBLISHED BY THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. VOL. XIX. PRINTED FOR THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. M.DCCC.XLIX. JAMES CROSSLEY, Esq., President. REV. RICHARD PARKINSON, B.D., F.S.A., Canon of Manchester and Principal of St. Bees College, Vice-President. WILLIAM BEAMONT. THE VERY REV. GEORGE HULL BOWERS, D.D., Dean of Manchester. REV. THOMAS CORSER, M.A. JAMES DEARDEN, F.S.A. EDWARD HAWKINS, F.R.S., F.S.A., F.L.S. THOMAS HEYWOOD, F.S.A. W. A. HULTON. REV. J. PICCOPE, M.A. REV. F. R. RAINES, M.A., F.S.A. THE VEN. JOHN RUSHTON, D.D., Archdeacon of Manchester. WILLIAM LANGTON, Treasurer. WILLIAM FLEMING, M.D., Hon. SECRETARY. ^ ^otttia €mtvitmis, HISTORICAL NOTICES OF THE DIOCESE OF CHESTER, RIGHT REV. FRANCIS GASTRELL, D.D. LORD BISHOP OF CHESTER. NOW FIRST PEINTEB FROM THE OEIGINAl MANITSCEIPT, WITH ILLrSTBATIVE AND EXPLANATOEY NOTES, THE REV. F. R. RAINES, M.A. F.S.A. BUBAL DEAN OF ROCHDALE, AND INCUMBENT OF MILNEOW. VOL. II. — PART I. ^1 PRINTED FOR THE GHETHAM SOCIETY. M.DCCC.XLIX. 1380748 CONTENTS. VOL. II. — PART I i¥lamf)e£{ter IBeanerp* page. -

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

OLD FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION Page 1 1. NAME of PROPERTY Historic Name

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 OLD FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Page 1 NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: OLD FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Other Name/Site Number: The Downtown Presbyterian Church 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 154 Fifth Avenue North Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Nashville Vicinity: N/A State: TN County: Davidson Code: 41 Zip Code: 37219 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Buildingfs): X Public-Local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 __ buildings sites structures objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

THE GILDED GARDEN Historic Ornament in the Landscape at Montgomery Place

DED GA GIL RD E E H N T Historic Ornament in the Landscape at Montgomery Place May 25 – October 31, 2019 1 THE GILDED GARDEN Historic Ornament in the Landscape at Montgomery Place In 1841, the renowned American architect Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–92) was hired to redesign the Mansion House at Montgomery Place, as well as consult on the surrounding grounds. Between 1841 and 1844, Davis introduced the property owners Louise Livingston, her daughter Cora, and son-in-law Thomas Barton to Exhibition produced in partnership with and curated by landscape designer, editor, and writer Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–52), the Barbara Israel and her staff from Barbara Israel Garden Antiques seminal figure now regarded by historians as the father of American landscape architecture. Downing had learned practical planting know-how at his family’s nursery, but he was more than an expert on botanical species. He was also a Funding provided by the A. C. Israel Foundation and tastemaker of the highest order who did more to influence the way Americans Plymouth Hill Foundation designed their properties than anyone else before or since. Raised in Newburgh, Downing was intensely devoted to the Hudson Valley region and was dedicated to his family’s nursery business there. In the 1830s, Downing began to make a name for himself as a writer, and contributed multiple articles on horticulture to various periodicals. Downing’s enormously influential work,A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America was published in 1841. It contained descriptions of the proper use of ornament, the importance of coherent design, use of native trees and plants, and his most important principle—that, when it came to designing a landscape, nature should be elevated and interpreted, not slavishly copied. -

Agecroft Power Stations Generated Together the Original Boiler Plant Had Reached 30 Years for 10 Years

AGECROl?T POWER STATIONS 1924-1993 - About the author PETER HOOTON joined the electricity supply industry in 1950 at Agecroft A as a trainee. He stayed there until his retirement as maintenance service manager in 1991. Peter approached the brochure project in the same way that he approached work - with dedication and enthusiasm. The publication reflects his efforts. Acknowledgements MA1'/Y. members and ex members of staff have contributed to this history by providing technical information and their memories of past events In the long life of the station. Many of the tales provided much laughter but could not possibly be printed. To everyone who has provided informati.on and stories, my thanks. Thanks also to:. Tony Frankland, Salford Local History Library; Andrew Cross, Archivist; Alan Davies, Salford Mining Museum; Tony Glynn, journalist with Swinton & Pendlebury Journal; Bob Brooks, former station manager at Bold Power Station; Joan Jolly, secretary, Agecroft Power Station; Dick Coleman from WordPOWER; and - by no means least! - my wife Margaret for secretarial help and personal encouragement. Finally can I thank Mike Stanton for giving me lhe opportunity to spend many interesting hours talkin11 to coUcagues about a place that gave us years of employment. Peter Hooton 1 September 1993 References Brochure of the Official Opening of Agecroft Power Station, 25 September 1925; Salford Local History Library. Brochure for Agecroft B and C Stations, published by Central Electricity Generating Board; Salford Local Published by NationaJ Power, History Library. I September, 1993. Photographic albums of the construction of B and (' Edited and designed by WordPOWER, Stations; Salford Local Histo1y Libraty. -

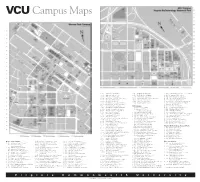

V I R G I N I a C O M M O N W E a L T H U N I V E R S I

VCU Campus Maps 50. (E-6) McAdams House, 914 W. Franklin St. 97. (A-10) VISSTA 4 Building, 1435 W. Main St. 39. (U-30) Pocahontas Building – VCU Computer Center, 900 E. Main St. 51. (C-9) Meeting Center, 101 N. Harrison St.* 98. (A-11) VISSTA 5 Building, 1401 W. Main St. 40. (R-30) Procurement Office, VCU, 10 S. 6th St.* 52. (D-5) Meredith House, 1014 W. Franklin St. 99. (F-4) Welcome Center, 1111 W. Broad St.* 41. (V-28) Putney House, Samuel, 1010 E. Marshall St. 53. (E-6) Millhiser Carriage House, 916 W. Franklin St. (Rear) 100. (H-7) West Grace Street Student Housing, 701 W. Grace St.* 42. (V-28) Putney House, Stephen, 1012 E. Marshall St. 54. (E-6) Millhiser House, 916 W. Franklin St. 101. (G-7) White House, 806 W. Franklin St. 43. (Y-29) Randolph Minor Hall, 301 College St.* 55. (D-8) Moseley House, 1001 Grove Ave. 102. (G-8) Williams House, 800 W. Franklin St. 44. (U-24) Recreation and Aquatic Center, 10th and Turpin streets* 56. (C-11) Oliver Hall-Physical Science Wing, 1001 W. Main St.* 103. (D-6) Younger House, 919 W. Franklin St. 45. (W-27) Richmond Academy of Medicine, 1200 E. Clay St.* 57. (C-12) Oliver Hall-School of Education, 1015 W. Main St.* 46. (U-25) Rudd Hall, 600 N. 10th St.* 58. (D-1) Parking, Bowe Street Deck, 609 Bowe St.* MCV Campus 47. (W-29) Sanger Hall, 1101 E. Marshall St.* 59. (F-4) Parking, West Broad Street Deck, 1111 W. -

PDF Download First Term at Tall Towers Kindle

FIRST TERM AT TALL TOWERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lou Kuenzler | 192 pages | 03 Apr 2014 | Scholastic | 9781407136288 | English | London, United Kingdom First Term at Tall Towers, Kids Online Book Vlogger & Reviews - The KRiB - The KRiB TV Retrieved 5 October Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Archived from the original on 20 August Retrieved 30 August Retrieved 26 July Cable News Network. Archived from the original on 1 March Retrieved 1 March The Daily Telegraph. Tobu Railway Co. Retrieved 8 March Skyscraper Center. Retrieved 15 October Retrieved Retrieved 27 March Retrieved 4 April Retrieved 27 December Palawan News. Retrieved 11 April Retrieved 25 October Tallest buildings and structures. History Skyscraper Storey. British Empire and Commonwealth European Union. Commonwealth of Nations. Additionally guyed tower Air traffic obstacle All buildings and structures Antenna height considerations Architectural engineering Construction Early skyscrapers Height restriction laws Groundscraper Oil platform Partially guyed tower Tower block. Italics indicate structures under construction. Petronius m Baldpate Platform Tallest structures Tallest buildings and structures Tallest freestanding structures. Categories : Towers Lists of tallest structures Construction records. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Wikimedia Commons. Tallest tower in the world , second-tallest freestanding structure in the world after the Burj Khalifa. Tallest freestanding structure in the world —, tallest in the western hemisphere. Tallest in South East Asia. Tianjin Radio and Television Tower. Central Radio and TV Tower. Liberation Tower. Riga Radio and TV Tower. Berliner Fernsehturm. Sri Lanka. Stratosphere Tower. United States. Tallest observation tower in the United States. -

Your GUIDE to RICHMOND the Vitamins and Nutrients Provided by IV Hydration Therapy Are 100 Percent Absorbed by Your Body!

YOUR GUIDE TO RICHMOND The vitamins and nutrients provided by IV hydration therapy are 100 percent absorbed by your body! IV hydration therapy benefits EVERYONE from athletes to weekend warriors. Our clinic was created to keep you on top of your game. When your body is dehydrated and low on critical elements it’s almost impossible to function well. Get a power boost that helps you achieve peak performance to get on with your day and feel good. Most common reasons that our patients undergo IV therapy include: Hangovers • Immunity • Athletic Training • General Wellness • Fatigue • PMS Cold/Flu • Pre or Post Workout Prep/Recovery • Migraines • Fibromyalgia Download our App or find us on Mindbody 2008 Bremo Road, Suite 111 | Richmond, VA 23226 | 493-4060 [email protected] | www.rivercityiv.com John MacLellan Photos & Design & Photos MacLellan John RICHMOND TRIANGLE PLAYERS PROUDLY PRESENTS OUR 25TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017–2018 THE RECENT OFF-BROADWAY SMASH HIT ABOUT A FORGOTTEN TIME AND PLACE THE NEW TESTAMENT TOLD IN A RADICALLY NEW WAY THE VIEW UPSTAIRS CORPUS CHRISTI by Max Vernon by Terrence McNally. AUGUST 9 – SEPTEMBER 2, 2017 Presented as a part of the city-wide Acts of Faith festival JANUARY 31 – FEBRUARY 24, 2018 THE SEX FARCE WITH GENDER POLITICS ON ITS MIND CLOUD 9 THE PROVOCATIVE CHRONICLE OF AMERICA’S DEADLIEST PLAGUE by Caryl Churchill. THE NORMAL HEART SEPTEMBER 20 – OCTOBER 14, 2017 by Larry Kramer. APRIL 18 – MAY 12, 2018 THE WACKY HOLIDAY HIT RETURNS! THE SANTALAND DIARIES THE MUSICAL LEGEND THAT CELEBRATES THE DANCER IN US ALL AND SEASON’S GREETINGS A CHORUS LINE by David Sedaris, adapted by Joe Mantello.