Categorization of Bilabial Stop Consonants by Bilingual Speakers of English and Polish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building a Universal Phonetic Model for Zero-Resource Languages

Building a Universal Phonetic Model for Zero-Resource Languages Paul Moore MInf Project (Part 2) Interim Report Master of Informatics School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2020 3 Abstract Being able to predict phones from speech is a challenge in and of itself, but what about unseen phones from different languages? In this project, work was done towards building precisely this kind of universal phonetic model. Using the GlobalPhone language corpus, phones’ articulatory features, a recurrent neu- ral network, open-source libraries, and an innovative prediction system, a model was created to predict phones based on their features alone. The results show promise, especially for using these models on languages within the same family. 4 Acknowledgements Once again, a huge thank you to Steve Renals, my supervisor, for all his assistance. I greatly appreciated his practical advice and reasoning when I got stuck, or things seemed overwhelming, and I’m very thankful that he endorsed this project. I’m immensely grateful for the support my family and friends have provided in the good times and bad throughout my studies at university. A big shout-out to my flatmates Hamish, Mark, Stephen and Iain for the fun and laugh- ter they contributed this year. I’m especially grateful to Hamish for being around dur- ing the isolation from Coronavirus and for helping me out in so many practical ways when I needed time to work on this project. Lastly, I wish to thank Jesus Christ, my Saviour and my Lord, who keeps all these things in their proper perspective, and gives me strength each day. -

Prestopped Bilabial Trills in Sangtam*

PRESTOPPED BILABIAL TRILLS IN SANGTAM* Alexander R. Coupe Nanyang Technological University, Singapore [email protected] ABSTRACT manner of articulation in an ethnographic description published in 1939: This paper discusses the phonetic and phonological p͜͜ w = der für Nord-Sangtam typische Konsonant, sehr features of a typologically rare prestopped bilabial schwierig auszusprechen; tönt etwa wie pw oder pr. trill and some associated evolving sound changes in Wird jedoch von den Lippen gebildet, durch die man the phonology of Sangtam, a Tibeto-Burman die Luft so preßt, daß die Untelippe einmal (oder language of central Nagaland, north-east India. zweimal) vibriert. (Möglicherweise gibt es den gleichen Konsonanten etwas weicher und wird dann Prestopped bilabial trills were encountered in two mit b͜ w bezeichnet). dozen words of a 500-item corpus and found to be in Translation: pw = the typical consonant for the North phonemic contrast with all other members of the Sangtam language, very difficult to pronounce; sounds plosive series. Evidence from static palatograms and like pw or pr. It is however produced by the lips, linguagrams demonstrates that Sangtam speakers through which one presses the air in a way that the articulate this sound by first making an apical- or lower lip vibrates once (or twice). (Possibly, the same laminal-dental oral occlusion, which is then consonant exists in a slightly softer form and is then 1 explosively released into a bilabial trill involving up termed bw). to three oscillations of the lips. In 2012 a similar sound was encountered in two The paper concludes with a discussion of the dozen words of a 500-word corpus of Northern possible historical sources of prestopped bilabial Sangtam, the main difference from Kauffman’s trills in this language, taking into account description being that the lip vibration is preceded phonological reconstructions and cross-linguistic by an apical- or laminal-dental occlusion. -

Saudi Speakers' Perception of the English Bilabial

Sino-US English Teaching, June 2015, Vol. 12, No. 6, 435-447 doi:10.17265/1539-8072/2015.06.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING Saudi Speakers’ Perception of the English Bilabial Stops /b/ and /p/ Mohammad Al Zahrani Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia Languages differ in their phoneme inventories. Some phonemes exist in more than one language but others exist in relatively few languages. More specifically, English Language has some sounds that Arabic does not have and vice versa. This paper focuses on the perception of the English bilabial stops /b/ and /p/ in contrast to the perception of the English alveolar stops /t/ and /d/ by some Saudi linguists who have been speaking English for more than six years and who are currently in an English speaking country, Australia. This phenomenon of perception of the English bilabial stops /b/ and /p/ will be tested mainly by virtue of minimal pairs and other words that may better help to investigate this perception. The paper uses some minimal pairs in which the bilabial and alveolar stops occur initially and finally. Also, it uses some verbs that end with the suffix /-ed/, but this /-ed/ suffix is pronounced [t] or [d] when preceded by /p/ or /b/ respectively. Notice that [t] and [d] are allophones of the English past tense morpheme /-ed/ (for example, Fromkin, Rodman, & Hyams, 2007). The pronunciation of the suffix as [t] and [d] works as a clue for the subjects to know the preceding bilabial sound. Keywords: perception, Arabic, stops, English, phonology Introduction Languages differ in their phoneme inventories. -

Acoustic Characteristics of Aymara Ejectives: a Pilot Study

ACOUSTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF AYMARA EJECTIVES: A PILOT STUDY Hansang Park & Hyoju Kim Hongik University, Seoul National University [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Comparison of velar ejectives in Hausa [18, 19, 22] and Navajo [36] showed significant cross- This study investigates acoustic characteristics of linguistic variation and some notable inter-speaker Aymara ejectives. Acoustic measurements of the differences [27]. It was found that the two languages Aymara ejectives were conducted in terms of the differ in the relative durations of the different parts durations of the release burst, the vowel, and the of the ejectives, such that Navajo stops are greater in intervening gap (VOT), the intensity and spectral the duration of the glottal closure than Hausa ones. centroid of the release burst, and H1-H2 of the initial In Hausa, the glottal closure is probably released part of the vowel. Results showed that ejectives vary very soon after the oral closure and it is followed by with place of articulation in the duration, intensity, a period of voiceless airflow. In Navajo, it is and centroid of the release burst but commonly have released into a creaky voice which continues from a lower H1-H2 irrespective of place of articulation. several periods into the beginning of the vowel. It was also found that the long glottal closure in Keywords: Aymara, ejective, VOT, release burst, Navajo could not be attributed to the overall speech H1-H2. rate, which was similar in both cases [27]. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.2. Aymara ejectives 1.1. Ejectives Ejectives occur in Aymara, which is one of the Ande an languages spoken by the Aymara people who live Ejectives are sounds which are produced with a around the Lake Titicaca region of southern Peru an glottalic egressive airstream mechanism [26]. -

Websites for IPA Practice

IPA review Websites for IPA practice • http://languageinstinct.blogspot.com/2006/10/stress-timed-rhythm-of-english.html • http://ipa.typeit.org/ • http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/phonetics.html • http://phonetics.ucla.edu/vowels/contents.html • http://accent.gmu.edu/browse_language.php • http://isg.urv.es/sociolinguistics/varieties/index.html • http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phonetics/english/frameset.html • http://usefulenglish.ru/phonetics/practice-vowel-contrast • http://www.unc.edu/~jlsmith/pht-url.html#(0) • http://www.agendaweb.org/phonetic.html • http://www.anglistik.uni-bonn.de/samgram/phonprac.htm • http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/phonetics/phonetics.html • http://www.englishexercises.org/makeagame/viewgame.asp?id=4767 • http://www.tedpower.co.uk/phonetics.htm • http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speech_perception • http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/sounds/changing-voices/ • http://www.mta.ca/faculty/arts-letters/mll/linguistics/exercises/index.html#phono • http://cla.calpoly.edu/~jrubba/phon/weeklypractice.html • http://amyrey.web.unc.edu/classes/ling-101-online/practice/phonology-practice/ Articulatory description of consonant sounds • State of glottis (voiced or voiceless) • Place of articulation (bilabial, alveolar, etc.) • Manner of articulation (stop, fricative, etc.) Bilabial [p] pit [b] bit [m] mit [w] wit Labiodental [f] fan [v] van Interdental “th” [θ] thigh [ð] thy Alveolar [t] tip [d] dip [s] sip [z] zip [n] nip [l] lip [ɹ] rip Alveopalatal [tʃ] chin [dʒ] gin [ʃ] shin [ʒ] azure Palatal [j] yes Velar [k] call [g] guy [ŋ] sing -

LING-001 Lecture 8: Phonetics

LING-001 Lecture 8: Phonetics Hilary Prichard 10/4/10 What is phonetics? The study of speech sounds From production to perception From Denes & Pinson, 1993 Three branches of phonetics Articulatory How speech is produced Acoustic Acoustic properties of speech Auditory How speech sounds are received and perceived Articulatory Phonetics How are speech sounds produced? The Vocal Tract The Larynx Contains the vocal folds (or cords) Air from the lungs passes through these folds When they are closed, the airflow causes them to vibrate The Vocal Folds in Action “Inside the Voice” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_ZGqn1tZn8&feature=player_embedded “High Speed Video of the Vocal Folds” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9kHdhbEnhoA&feature=player_embedded The Articulators The parts of the vocal tract which are used to shape the sound Consonants Place of Articulation Which parts of the vocal tract are involved? Manner of Articulation What type of closure is created by the articulators? Place of Articulation Bilabial: made with both lips [p b m] Labiodental: made with lower lip and upper teeth [f v] Place of Articulation Dental: Tongue & upper front teeth [ð θ] Alveolar: Tongue & alveolar ridge [t d n s z] Place of Articulation Post-Alveolar: (palato-alveolar) Tongue & back of the alveolar ridge [∫ʒ] Palatal: Tongue & hard palate [j] Velar: Tongue & soft palate (velum) [k g ŋ] Manner of Articulation Stop: (plosive) complete closure, no air escapes through the mouth Oral Stop: Velum is raised; air cannot escape through the -

![[Sawndz] Sounds of English Words Letters Or Sounds? Solution](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3381/sawndz-sounds-of-english-words-letters-or-sounds-solution-3273381.webp)

[Sawndz] Sounds of English Words Letters Or Sounds? Solution

[sawndz] Sounds of English Words Phonetics: the science of speech sounds (Part 1) Letters or Sounds? • fun, phonetics, enough • eye, night, site, by, buy, I • met, meet, petunia, resume, mite, Solution The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) one sound -- one letter! Usually written between [´] or /´/ brackets 1 Articulatory Phonetics • Speech sounds are characterized in terms of segments of sounds (segments are the phonetic equivalent of letters). • Different sounds are made in a manner very similar to the way in which different sounds come out of a trumpet or clarinet • Blow air through a sound-creating device (eg reed or mouth piece or vocal cords) • Change shape of tube to give different acoustics (pressing keys, covering holes, moving tongue, lips etc. The Sound Producing Nasal cavity: tube shape 3 System Pharynx: tube Oral cavity: shape 1 tube shape 2 Larynx -- the sound source Lungs: the source of airflow Stages in Speech Production • Initiation – muscles force air up from the lungs • Phonation – the air passes through the larynx, the vocal cords may/may not vibrate • Articulation – the air passes through the oral cavity (mouth) and the shape of the cavity and placement of the articulators affects the resultant sound 2 Major Classes of Sounds • Distinguish 3 major classes of sounds: – Consonants – Glides (semi vowels) – Vowels These are distinguished in terms of the amount of airflow through the vocal mechanism The description of consonants • Place of Articulation (where they are said) • Manner of Articulation(how they are said) • Voicing (whether your vocal cords are vibrating or not) Voicing • Put your hand on your throat and say the following words: – Sing, think, final, bush – Zing, though, vinal, garage • Sounds without vocal cord vibration are voiceless • Sounds with vocal cord vibration are voiced. -

2 the Sounds of Language: Consonants

Week 2. Instructor: Neal Snape ([email protected]) 2 The sounds of language: Consonants PHONETICS: The science of human speech sounds; describing sounds by grouping sounds into classes - similarities distinguishing sounds - differences SOUNDS: CONSONANTS & VOWELS (GLIDES) - defined by the constriction of the air channel CONSONANTS: Sounds made by constricting the airflow from the lungs. - defined by: the PLACE of articulation (where is the sound made?) and the MANNER of articulation (How is the sound made?) PLACE: Bilabial: [p, b, m] both lips Labio-dental: [f, v] lip & teeth Dental: [†, ∂] tongue tip & teeth Alveolar: [t, d, s, z, l, r, n] tongue tip & AR* Palato-alveolar: [ß, Ω, ß, Ω] tongue blade & AR/ hard palate Palatal: [j] tongue (front) & hard palate Velar: [k, g, Ñ] tongue (back) & velum Labio-velar: [w] lips & tongue (back) & velum Glottal: [h, ÷] vocal cords (glottis) * AR = alveolar ridge MANNER: Plosives: [p, b, t, d, k, g, ÷] closure Fricatives: [f, v, †, ∂, s, z, ß, Ω, h] friction Affricates: [ß,Ω] combination Nasals: [m, n, Ñ] nasal cavity Liquid: [l, r] partly blocked Glides: [w, j] vowel-like 1 Manner of articulation is about how the sound is produced. It is divided into two types: obstruents (obstruction the air-stream causing the heightened air- pressure) and sonorants (no increase of the air-pressure). Then, each of them is further divided into as follows: Manners of articulation Obstruents Sonorants Stops Fricatives Affricates Nasals Approximants (closure → release) (friction) (closure → friction) (through nose) (partial block + free air-stream) Liquids Glides Rhotics Laterals (through center (through sides of tongue) of tongue) Figure 1. -

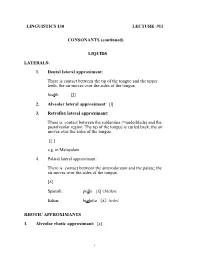

1. Dental Lateral Approximant: There Is Contact Between the Tip of the Tongue and the Upper Teeth; the Air Moves Over the Sides of the Tongue

LINGUISTICS 130 LECTURE #11 CONSONANTS (continued) LIQUIDS LATERALS: 1. Dental lateral approximant: There is contact between the tip of the tongue and the upper teeth; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. health [l∞] 2. Alveolar lateral approximant: [l] 3. Retroflex lateral approximant: There is contact between the sublamina (=underblade) and the postalveolar region. The tip of the tongue is curled back; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. [Æ ] e.g. in Malayalam 4. Palatal lateral approximant: There is contact between the anterodorsum and the palate; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. [Ò] Spanish: pollo [Ò] chicken Italian: bigletto [Ò] ticket RHOTIC APPROXIMANTS 1. Alveolar rhotic approximant: [®] 1 2. Retroflex rhotic approximant: The sublamina approximates the postalveolar region while the tip of the tongue is curled back. [ï] FLAPS The active articulator (tip of the tongue) strikes the place of articulation, and after momentary contact it immediately withdraws. MOMENTARY CONTACT BETWEEN TWO ARTICULATORS! Alveolar flaps: the tip of the tongue makes momentary contact with the alveolar ridge. Common in North American English: [‰] alveolar flap (voiced) Betty, writer, rider [‰] TRILLS One articulator is held loosely near to another so that the flow of air between them sets one of the articulators (e.g. the tongue) in motion, alternately sucking them together and blowing them apart. There are usually three vibrating movements in a typical trill. 1. Alveolar trill: apex articulators alveolar ridge [r] (voiced) Finnish: raha [r] money 2 2. Uvular trill: dorsum articulators uvula [R] (voiced) It occurs in some varieties of French instead of the uvular fricative. -

A Descriptive Alphabet 1 the Hangulphabet

The Hangulphabet: A Descriptive Alphabet 1 The Hangulphabet: A Descriptive Alphabet Robert Bishop and Ruggero Micheletto Yokohama City University {rbishop}@yokohama-cu.ac.jp Yokohama City University International College of Arts and Sciences 22-2 Seto, Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama-shi, 236-0027 Japan Abstract This paper describes the Hangulphabet, a new writing system that should prove useful in a number of contexts. Using the Hangulphabet, a user can instantly see voicing, manner and place of articulation of any phoneme found in human language. The Hangulphabet places consonant graphemes on a grid with the x-axis representing the place of articulation and the y-axis representing manner of articulation. Each individual grapheme contains radicals from both axes where the points intersect. The top radical represents manner of articulation where the bottom represents place of articulation. A horizontal line running through the middle of the bottom radical represents voicing. For vowels, place of articulation is located on a grid that represents the position of the tongue in the mouth. This grid is similar to that of the IPA vowel chart (International Phonetic Association, 1999). The difference with the Hangulphabet being the trapezoid representing the vocal apparatus is on a slight tilt. Place of articulation for a vowel is represented by a breakout figure from the grid. This system can be used as an alternative to the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) or as a complement to it. Beginning students of linguistics may find it particularly useful. A Hangulphabet font has been created to facilitate switching between the Hangulphabet and the IPA. Keywords: The International Phonetic Alphabet, Alternative Writing systems, Teaching Phonology, Hangul Introduction The Hangulphabet is a new alphabet that represents both place and manner of articulation in one grapheme. -

Prenasalization and Trilled Release of Two Consonants in Nias Brendon Yoder SIL-UND

Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session Volume 50 Article 3 2010 Prenasalization and trilled release of two consonants in Nias Brendon Yoder SIL-UND Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/sil-work-papers Part of the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Yoder, Brendon (2010) "Prenasalization and trilled release of two consonants in Nias," Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session: Vol. 50 , Article 3. DOI: 10.31356/silwp.vol50.03 Available at: https://commons.und.edu/sil-work-papers/vol50/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prenasalization and trilled release of two consonants in Nias Brendon Yoder SIL International This paper presents an acoustic study of the phonetic realization of two consonants in Nias (Indonesia), orthographically represented as mb and ndr. These consonants have been analyzed by Catford (1988) and Brown (2001, 2005) as a bilabial trill and an apical trill, respectively. My own cross-dialectal observations indicate that these consonants have multiple realizations in each dialect. This paper presents evidence for four broad phonetic realizations of both mb and ndr: most commonly a plain stop, but also a prenasalized stop, a stop with trilled release, and stop with fricated release. It seems that the variable character of the two phonemes is the only consistent feature that distinguishes them from the regular stops in the same places of articulation, and from the regular alveolar trill.* 1. -

International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) in English There Is No Simple

417-131 Practical Phonetics International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) In English there is no simple relationship between spelling and sounds. As a result, people have invented different systems to represent English sounds. These systems use one letter or symbol for each sound. An alphabetic system with one symbol representing one sound is a phonetic alphabet. The phonetic alphabet includes most of the twenty-six letters of the alphabet, along with some new symbols. We write these phonetic letters and symbols between bracket marks. For example, the symbols [k], [l] and [ae] represent sounds, not letters. One phonetic symbol represents only one sound. The following charts list the phonetic symbols for all the consonant and vowel sounds of American English. Most of these sounds occur in initial (beginning), medial (middle), and final (end) positions. There are examples for each sound. Memorize one key word. It will help you remember the sound for each phonetic symbol. Your dictionary: ............................................ Symbols Find an example IPA Description used in of words for each your sound in your dictionary dictionary. [p] voiceless unaspirated bilabial stop [pʰ] voiceless aspirated bilabial stop [b] voiced bilabial stop [t] voiceless unaspirated apico-alveolar stop [tʰ] voiceless aspirated apico-alveolar stop [d] voiced apico-alveolar stop [k] voiceless unaspirated dorso-velar stop [kʰ] voiceless aspirated dorso-velar stop [g] voiced dorso-velar stop [f] voiceless labio-dental fricative [v] voiced labio-dental fricative [θ] voiceless