Verdun00henr.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“They Shall Not Pass!” Fortifications, from the Séré De Rivières System to the Maginot Line

VERDUN MEMORIAL - BATTLEFIELD Press release April 2021 Temporary exhibition 3 June 2021 – 17 December 2021 “THEY SHALL NOT PASS!” FORTIFICATIONS, FROM THE SÉRÉ DE RIVIÈRES SYSTEM TO THE MAGINOT LINE To accompany the 1940 commemorations, the Verdun Memorial will be presenting an exhibition on the fortifications in northern and eastern France. The soldiers’ experience is at the heart of the visit: “They shall not pass!” The exhibition traces the development of defensive systems along the frontier between France and Germany, which had historically always been an area of combat with shifting borders. Subject to regular attack, the fortifications were modernised to withstand the increasingly powerful means of destruction resulting from rapid advances in artillery. “They shall not pass!” Fortifications, from the Séré de Rivières System to the Maginot Line, will re-evaluate the role of the Maginot Line in the defeat of June 1940, re-examining the view that it was a mistake inevitably leading to defeat, in particular due to a lack of fighting spirit on the part of the French troops. The exhibition aims to explain the Maginot Line by going back in time and seeing it in relation to the different types of fortification that had appeared following France’s defeat in the Franco- Prussian War in 1870. It traces the development of successive defensive systems and the life of their garrisons, from the Séré de Rivières System of the end of the 19th century, via the Verdun fortification during the First World War, to the Maginot Line (1929-1939), the high point of French defensive engineering. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

First Battle of the Marne After Invading Belgium and North-Eastern France

First Battle of the Marne After invading Belgium and north-eastern France during the Battle of Frontiers, the German army had reached within 30 miles of Paris. Their progress had been rapid, giving the French little time to regroup. The First Battle of the Marne was fought between September 6th through the 12th in 1914, with the German advance being brought to a halt, and a stalemate and trench warfare being established as the norm. As the German armies neared Paris, the French capital prepared itself for a siege. The defending French and British forces were at the point of exhaustion, having retreated continuously for 10-12 days under repeated German attack until they had reached the south of the River Marne. Nevertheless, the German forces were close to achieving a breakthrough against the French forces, and were only saved on the 7th of September by the aid of 6,000 French reserve infantry troops brought in from Paris by a convoy of taxi cabs, 600 cabs in all. On September 9th, the German armies began a retreat ordered by the German Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke. Moltke feared an Allied breakthrough, plagued by poor communication from his lines at the Marne. The retreating armies were pursued by the French and British, although the pace of the Allied advance was slow - a mere 12 miles in one day. The German armies ceased their withdrawal after 40 miles at a point north of the River Aisne, where the First and Second Armies dug in, preparing trenches that were to last for several years. -

BCMH First World War Occasional Paper

British Commission for Military History First World War Occasional Paper No. 1 (2015) The Battle of Malmaison - 23-26 October 1917 ‘A Masterpiece of Tactics’ Tim Gale BCMH First World War Occasional Paper The British Commission for Military History’s First World War Occasional Papers are a series of research articles designed to support people’s research into key areas of First World War history. Citation: Tim Gale, ‘The Battle of Malmaison - 23-26 October 1917: ‘A Masterpiece of Tactics’’, BCMH First World War Occasional Paper, No. 1 (2015) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The Battle of Malmaison Page 2 BCMH First World War Occasional Paper Abstract: This occasional paper explores the background, planning, conduct and aftermath of the Battle of Malmaison in October 1917. The Battle of Malmaison was not a large battle by the standards of the First World War; however, it was of crucial importance in the development of French military thought during the war and it was a significant moment in the process of restoring morale within the French army. About the Author: Dr Tim Gale was awarded his PhD by the Department of War Studies, King's College London for his work on French tank development and operations in the First World War. He has contributed chapters on this subject in several academic books, as well as other work on the French Army during the First World War. Tim has made a special study of the career of the controversial French First World War General, Charles Mangin. -

World War I Press

press pACK GREAt war CentenarY Vimy Canadian memorial Fromelles national Australian memorial Notre-Dame-de-Lorette Dragon’s cave, Musée du chemin des Dames National Necropolis NORD - Vauquois Hills PAS DE Lille CALAIS Lens Étaples Arras Douaumont Ossuary Memorial to the missing Thiepval Amiens Péronne Laon Charleville Historial PICARDY Mezières of the Great War Compiègne Metz Soissons Reims Verdun ILE-DE-FRANCE Strasbourg La Fontenelle Paris Nancy Necropolis ALSACE Troyes LORRAINE CHAMPAGNE- ARDENNE Épinal Colmar Museum of the Great War, Chaumont Pays de Meaux American remembrance sites of Belleau WESTERN FRONT LINE Fort de la Pompelle Hartmannswillerkopf memorial Dormans, the battles of the Marne memorial London Brussels Nord - Pas de Calais Lille Upper Amiens Normandy Picardie Rouen Caen Lower Reims Alsace Paris Nancy Normandy Strasbourg Ile de Lorraine Brittany France Champagne- Ardenne Rennes Centre Franche- Comté Pays de la Loire Tours Dijon Besançon Nantes Bourgogne Poitiers Poitou- Charentes Limoges Clermont Ferrand Lyon Limousin Rhône-Alpes Auvergne Grenoble Bordeaux Aquitaine Midi-Pyrénées Provence - Montpellier Alpes Côte d'Azur Toulouse Marseille Languedoc Roussillon Corsica Ajaccio ATout frANCe - 2 1914 - 2014 FRANCE COMMEMORATES THE GRE AT WA R ATout frANCe - 3 ATout frANCe - 4 CONTENTS Introduction 7 1 Major Events commemorating the Great War 8 2 New site openings and renovations 14 3 Paris, gateway into France 17 4 Remembrance Trails 19 Nord-Pas de Calais 20 Somme: circuit of remembrance 24 Aisne 1914-1918 27 Champagne-Ardenne 31 Lorraine: Verdun, epicentre of Lorraine Battles of 3 Frontiers 35 The Great War on the Vosges Front 38 5 Appendices Atout France, France tourism development agency 42 The Centenary Mission 42 “Tourism and Great War Remembrance - The tourist network of the Western Front” 42 ATout frANCe - 5 ATout frANCe - 6 INTRODUCTION From August 1914 to November 1918, France was the stage for the most violent and deadly war that history had ever known. -

In the Trenches: a First World War Diary

In the Trenches: A First World War Diary By Pierre Minault Translated by Sylvain Minault Edited by Gail Minault Edited for Not Even Past by Mark Sheaves Originally published on Not Even Past <notevenpast.org> Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin September 22-November 16, 2014 © Not Even Past In the Trenches Pierre Minault’s Diary of the First World War Not Even Past is marking the centennial of the outbreak of the first World War with a very special publication. Our colleague, Gail Minault, a distinguished professor of the history of India, has given us her grandfather’s diary, a near daily record of his experiences in the trenches in France. Pierre Minault made his first diary entry on this very day, September 22, one hundred years ago, in 1914. We will be posting each of his entries exactly one hundred years after he wrote them. You will be able to follow Pierre’s progress and read his thoughtful and moving personal observations of life on the front as day follows day. Sylvain Minault originally translated the diary from French. Gail Minault edited this translation and added the following introduction. We are extremely grateful to her for sharing her grandfather’s diary with all of us. Introduction By Gail Minault This year we commemorate the outbreak of World War I, which began in August 1914, with all the powers of Europe declaring war on each other in a domino effect born of alliances and ententes. Reading the history of the war, one becomes aware of the carnage, the stalemate, the sacrifice of an entire generation of young men to great power politics. -

U.S. Army Military History Institute WWI-Western Front-1916 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 7 Oct 2011

U.S. Army Military History Institute WWI-Western Front-1916 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 7 Oct 2011 VERDUN, Feb-Dec 1916 A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources German and Allied High Commands each planned operations in 1916 that would break the stalemate and secure a victory on the Western Front. The Anglo-French alliance devised a summer breakthrough assault on the German lines through the Ancre and Somme River valleys. As the centerpiece on a war of attrition, the Germans planned a massive attack on the French fortress city of Verdun. The Kaiser and his commanders believed the French would present a strong and vigorous defense of Verdun for symbolic as much as for military reasons. Since the 18th century, Verdun had been a vital defensive position on the westbound approach to Paris. In 1792 it had fallen to a Prussian army and in 1870 to the Germans after a six-week siege during the Franco-Prussian War. By 1915, the German front line was ten miles from the city center. Verdun itself was defended by 500,000 troops and a ring of fortifications, the most prominent of which were Forts Douamont, Vaux and Souville. The 21 Feb attack by 1 million German troops initiated a battle that continued for ten months, during which counterattacks merely reinforced resolve on both sides. During a one-month period, the front line between Forts Douamont and Vaux fluctuated less than 1,000 yards (Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History, p. 235). CONTENTS General Sources.....p.2 Specific Locations -Ft Douamont.....p.4 -Ft. -

Copyright © 2016 by Bonnie Rose Hudson

Copyright © 2016 by Bonnie Rose Hudson Select graphics used by permission of Teachers Resource Force. All Rights Reserved. This book may not be reproduced or transmitted by any means, including graphic, electronic, or mechanical, without the express written consent of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews and those uses expressly described in the following Terms of Use. You are welcome to link back to the author’s website, http://writebonnierose.com, but may not link directly to the PDF file. You may not alter this work, sell or distribute it in any way, host this file on your own website, or upload it to a shared website. Terms of Use: For use by a family, this unit can be printed and copied as many times as needed. Classroom teachers may reproduce one copy for each student in his or her class. Members of co-ops or workshops may reproduce one copy for up to fifteen children. This material cannot be resold or used in any way for commercial purposes. Please contact the publisher with any questions. ©Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com 2 World War I Notebooking Unit The World War I Notebooking Unit is a way to help your children explore World War I in a way that is easy to personalize for your family and interests. In the front portion of this unit you will find: How to use this unit List of 168 World War I battles and engagements in no specific order Maps for areas where one or more major engagements occurred Notebooking page templates for your children to use In the second portion of the unit, you will find a list of the battles by year to help you customize the unit to fit your family’s needs. -

Processes of Tactical Learning in a WWI German Infantry Division1

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 13, ISSUE 4, Summer 2011 Studies Strategy "in a microcosm": Processes of tactical learning in a WWI German Infantry Division1 Christian Stachelbeck Despite the defeat of 1918, the tactical warfare of German forces on the battlefields against a superior enemy coalition was often very effective. The heavy losses suffered by the allies until well into the last months of the war are evidence of this.2 The tactical level of military action comprises the field of direct battle with forces up to division size. Tactics – according to Clausewitz, the “theory of the use of military forces in combat” – is the art of commanding troops and their organized interaction in combined arms combat in the types of combat which characterized the world war era – attack, defense and delaying engagement.3 1 This paper is based on my book Militärische Effektivität im Ersten Weltkrieg. Die 11. Bayerische Infanteriedivision 1915-1918, Paderborn et al. 2010 (=Zeitalter der Weltkriege, 6). It is also a revised version of my paper: “Autrefois à la guerre, tout était simple“. La modernisation du combat interarmes à partir de l’exemple d’une division d’infanterie allemande sur le front de l’Ouest entre 1916 et 1918. In: Revue Historique des Armées, 256 (2009), pp. 14-31. 2 See Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War (New York: Basic Books, 1999). 3 See Gerhard P. Groß, Das Dogma der Beweglichkeit. Überlegungen zur Genese der deutschen Heerestaktik im Zeitalter der Weltkriege. In: Erster Weltkrieg - Zweiter Weltkrieg. Ein Vergleich. Krieg, Kriegserlebnis, Kriegserfahrung in Deutschland, on behalf of Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Military History Research Institute) edited by Bruno Thoß and Hans-Erich Volkmann, Paderborn et al. -

A Five Year Legacy Project Involving the Entire School

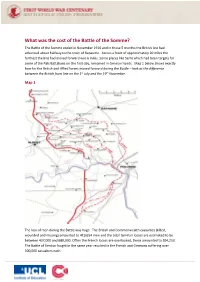

What was the cost of the Battle of the Somme? The Battle of the Somme ended in November 1916 and in those 5 months the British line had advanced about halfway to the town of Bapaume. Across a front of approximately 20 miles the furthest the line had moved forward was 6 miles. Some places like Serre which had been targets for some of the Pals Battalions on the first day, remained in German hands. Map 1 below shows exactly how far the British and Allied forces moved forward during the Battle – look at the difference between the British front line on the 1st July and the 19th November. Map 1 The loss of men during the Battle was huge. The British and Commonwealth casualties (killed, wounded and missing) amounted to 419,654 men and the total German losses are estimated to be between 437,000 and 680,000. Often the French losses are overlooked, these amounted to 204,253. The Battle of Verdun fought in the same year resulted in the French and Germans suffering over 300,000 casualties each. There was also an enormous personal cost – many villages, towns and cities in Britain were affected by the losses at the Battle of the Somme, especially communities that had raised Pals Battalions of volunteer soldiers. The cost of the Somme might be measured in other ways. In 1914 Britain’s National Debt amounted to £700 million, in July 1916 this had risen to £2,500 million. By the end of the War it had risen to £7,500 million. -

One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research

Bretislav Friedrich · Dieter Hoffmann Jürgen Renn · Florian Schmaltz · Martin Wolf Editors One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences Bretislav Friedrich • Dieter Hoffmann Jürgen Renn • Florian Schmaltz Martin Wolf Editors One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences Editors Bretislav Friedrich Florian Schmaltz Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Max Planck Institute for the History of Society Science Berlin Berlin Germany Germany Dieter Hoffmann Martin Wolf Max Planck Institute for the History of Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Science Society Berlin Berlin Germany Germany Jürgen Renn Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Berlin Germany ISBN 978-3-319-51663-9 ISBN 978-3-319-51664-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-51664-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017941064 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncom- mercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. -

The First World War: Stalemate Tier 3 Vocabulary Definition Section 2: Key Battles of the Western Front Section 3: Chronology

Section 1: Key Vocabulary Subject: History Year: 9 Summer 1— The First World War: Stalemate Tier 3 vocabulary Definition Section 2: Key Battles of the Western Front Section 3: Chronology Battle of Verdun The Schlieffen Plan German battle plan made in Sept 1914 Battle of the Marne: Battle which took (n) 1905 by General Von Verdun was fought in February 1916 place in September 1914 by the river Marne Schlieffen. Aim to avoid a war in France. France were pushing Germany Between the French and the Germans. on two fronts by invading back. Argued to be a turning point in the France through Belgium whilst This 6 month battle lead to the war of attrition. war. Russia armed. By July 700,000 men had lost their lives. Oct 1914 The Race to the Sea: An attempt to ‘out Western Front (n) A line of trenches ranging from flank’ (get around the end off) the French the sea to the Alps. Battle of the Somme troops; took place on 12th October. German troops moved towards the sea and British ANZAC (n) Australian and New Zealand's Took place in July 1916 and French troops attempted to stop them. troops. Fought by the English and the Germans. Zeppelin (n) Large bomber airship Nov 1914 Trench warfare began It began mainly to relieve pressure for the French at Verdun. No man’s land (n) An area of land between two April 1915 First poison gas attack countries or armies that is not 1.25 million men lost their life. controlled by anyone. Feb 1915 Gallipoli Campaign started Battle of Passchendaele U-Boat (n) Underwater boats— Feb1916 Battle of Verdun: The German attempt in submarines.