Monitoring Coral Reef Marine Protected Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salt Point State Marine Conservation Area North Central California Marine Protected Areas (Mpas), Established May 2010

Salt Point State Marine Conservation Area North Central California Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), Established May 2010 Red abalone Blue rockfish Salt Point SMCA (Haliotis rufescens) (Sebastes mystinus) Photo by Brian Owens Photo by CDFW Photo by Kevin Joe Site Overview Photos are representative of the North Central Coast Region and may not be within this MPA. What is an MPA? MPAs are a type of marine managed area (MMA) where marine or estuarine waters are set aside primarily to protect or conserve marine life and associated habitats. California has a coastal network of 124 protected areas designed to help increase the coherence and effectiveness of protecting the state’s marine life, habitats, and ecosystems. The network includes three types of MPA: state marine reserve (SMR), state marine conservation area (SMCA), and state marine park (SMP); one MMA: state marine recreational management area (SMRMA); and special closures. There are 119 MPAs, 5 MMAs and 15 special closures, each with unique boundaries and regulations in the network. Non-consumptive activities, restoration, and permitted scientific research are allowed. What is an SMCA? An SMCA is a type of MPA that protects resources by allowing for only specific types of recreational and/or commercial take to occur. (Area restrictions are defined in Title 14, Section 632(a)(1)(C)). Salt Point SMCA Overview Salt Point SMCA Key Habitats MPA size: 1.84 square miles Beaches: 0.62 miles Depth range: 0 to 226 feet Rocky shores: 4.30 miles Along-shore span (shoreline): 2.40 miles Sand (all depths): 1.14 square miles Rock (all depths): 0.40 square miles Where is Salt Point SMCA? Average Kelp (1989 to 2008): 0.11 square miles Unidentified (all depths): 0.28 square miles Boundaries and Regulations Boundary: This area is bounded by the mean high tide line and straight lines connecting the following points in the order listed: 38° 35.600' N. -

Status of Alcyonacean Corals Along Tuticorin Coast of Gulf of Mannar, Southeastern India

Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences Vol. 43(4), April 2014, pp. 666-675 Status of Alcyonacean corals along Tuticorin coast of Gulf of Mannar, Southeastern India S. Rajesh, K. Diraviya Raj, G. Mathews, T. Sivaramakrishnan & J.K. Patterson Edward Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute 44-Beach Road, Tuticorin – 628 001, Tamil Nadu, India [E-mail: [email protected]] Received 28 November 2012; revised 7 December 2012 In this study, the assessment of alcyonaceans was conducted in Tuticorin coast of the Gulf of Mannar during the period between 2010 and 2012 in 5 locations; Vaan, Koswari, Kariyachalli and Vilanguchalli islands and mainland Punnakayal patch reef. Average alcyonacean coral cover in Tuticorin coast was 6.76% during 2011-12 which was 5.61% during 2010- 2011. Percentage cover of alcyonacean corals increased in all the study locations; Kariyachalli 12.04 to 13.96%; Vilanguchalli 8.94 to 10.23%; Koswari 1.6 to 3.69; Vaan 0.53 to 0.72; mainland Punnakayal patch reef 4.95 to 5.21% was documented. In total, 15 species from 7 genera were recorded during the study period. Though anthropogenic threats in Tuticorin coast are comparatively high, the abundance of alcyonacean corals has increased considerably showing their resilience and adaptability. [Keywords: Alcyonacean corals, Status, Diversity, Tuticorin, Gulf of Mannar] Introduction experience all the natural and anthropogenic threats. Alcyonacean corals (soft corals and gorgonians) Reef ecosystems of Gulf of Mannar are heavily are modular cnidarians composed of polyps that stressed due to various human induced threats like always have eight tentacles and are oftentimes destructive and over fishing practices, coral mining, connected by vessels classified under subclass domestic and industrial pollution, seaweed and other Octocorallia while hard corals have six tentacles resource collection in reef areas and invasion of (which are hexa corals). -

Coral Reef Protection in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Intercoast #34 ______

_____________________________________________________________________________ Coral Reef Protection in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Intercoast #34 _____________________________________________________________________________ Bezaury, Juan and Jennifer McCann 1999 Citation: Narragansett, Rhode Island USA: Coastal Resources Center.InterCoast Network Newsletter, Spring 1999 For more information contact: Pamela Rubinoff, Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island. 220 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, RI 02882 Telephone: 401.874.6224 Fax: 401.789.4670 Email: [email protected] This five year project aims to conserve critical coastal resources in Mexico by building capacity of NGOs, Universities, communities and other key public and private stakeholders to promote an integrated approach to participatory coastal management and enhanced decision-making. This publication was made possible through support provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Office of Environment and Natural Resources Bureau for Economic Growth, Agriculture and Trade under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. PCE-A-00-95-0030-05. INTERNATIONAL NEWSLETTER OF COASTAL MANAGEMENT Narragansett, Rhode Island, U.S.A. • #31 • Spring, 1998 Protecting the Maya Reef Intercoast Through Multi-National Survey Results Cooperation Show Diverse manage their coastal resources region- Readership By Juan Bezaury and ally. The overall goal is to take advan- Jennifer McCann tage of growing opportunities for sus- ore than 200 people tainable development, -

Marine Nature Conservation in the Pelagic Environment: a Case for Pelagic Marine Protected Areas?

Marine nature conservation in the pelagic environment: a case for pelagic Marine Protected Areas? Susan Gubbay September 2006 Contents Contents......................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive summary....................................................................................................................... 2 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................... 4 2 The pelagic environment....................................................................................................... 4 2.1 An overview...................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Characteristics of the pelagic environment ....................................................................... 5 2.3 Spatial and temporal structure in the pelagic environment ............................................... 6 2.4 Marine life....................................................................................................................... 10 3 Biodiversity conservation in the pelagic environment........................................................ 12 3.1 Environmental concerns.................................................................................................. 12 3.2 Legislation, policy and management tools...................................................................... 15 -

SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK of Lmainland FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM GBRMPA-TM-14 SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK OF lMAINLAND FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA D.P. JOHNSON and RM.CARTER Department of Geology James Cook University of North Queensland Townsville, Q 4811, Australia DATE November, 1987 SUMMARY Mainland fringing reefs with a diverse coral fauna have developed in the Cape Tribulation area primarily upon coastal sedi- ment bodies such as beach shoals and creek mouth bars. Growth on steep rocky headlands is minor. The reefs have exten- sive sandy beaches to landward, and an irregular outer margin. Typically there is a raised platform of dead nef along the outer edge of the reef, and dead coral columns lie buried under the reef flat. Live coral growth is restricted to the outer reef slope. Seaward of the reefs is a narrow wedge of muddy, terrigenous sediment, which thins offshore. Beach, reef and inner shelf sediments all contain 50% terrigenous material, indicating the reefs have always grown under conditions of heavy terrigenous influx. The relatively shallow lower limit of coral growth (ca 6m below ADD) is typical of reef growth in turbid waters, where decreased light levels inhibit coral growth. Radiocarbon dating of material from surveyed sites confirms the age of the fossil coral columns as 33304110 ybp, indicating that they grew during the late postglacial sea-level high (ca 5500-6500 ybp). The former thriving reef-flat was killed by a post-5500 ybp sea-level fall of ca 1 m. Although this study has not assessed the community structure of the fringing reefs, nor whether changes are presently occur- ring, it is clear the corals present today on the fore-reef slope have always lived under heavy terrigenous influence, and that the fossil reef-flat can be explained as due to the mid-Holocene fall in sea-level. -

Chesapeake Bay Trust Hypoxia Project

Chesapeake Bay dissolved oxygen profiling using a lightweight, low- powered, real-time inductive CTDO2 mooring with sensors at multiple vertical measurement levels Doug Wilson Caribbean Wind LLC Baltimore, MD Darius Miller SoundNine Inc. Kirkland, WA Chesapeake Bay Trust EPA Chesapeake Bay Program Goal Implementation Team Support This project has been funded wholly or in part by the United States Environmental Protection Agency under assistance agreement CB96341401 to the Chesapeake Bay Trust. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Environmental Protection Agency, nor does the EPA endorse trade names or recommend the use of commercial products mentioned in this document. SCOPE 8: “…demonstrate a reliable, cost effective, real-time dissolved oxygen vertical monitoring system for characterizing mainstem Chesapeake Bay hypoxia.” Water quality impairment in the Chesapeake Bay, caused primarily by excessive long-term nutrient input from runoff and groundwater, is characterized by extreme seasonal hypoxia, particularly in the bottom layers of the deeper mainstem (although it is often present elsewhere). In addition to obvious negative impacts on ecosystems where it occurs, hypoxia represents the integrated effect of watershed-wide nutrient pollution, and monitoring the size and location of the hypoxic regions is important to assessing Chesapeake Bay health and restoration progress. Chesapeake Bay Program direct mainstem water quality monitoring has been by necessity widely spaced in time and location, with monthly or bi-monthly single fixed stations separated by several kilometers. The need for continuous, real time, vertically sampled profiles of dissolved oxygen has been long recognized, and improvements in hypoxia modeling and sensor technology make it achievable. -

Marine Biodiversity and International Law: Instruments and Institutions That Can Be Used to Conserve Marine Biological Diversity Internationally

MARINE BIODIVERSITY AND INTERNATIONAL LAW: INSTRUMENTS AND INSTITUTIONS THAT CAN BE USED TO CONSERVE MARINE BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY INTERNATIONALLY SUZANNE IUDICELLO* MARGARET LYTLE† I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 124 A. What is Marine Biodiversity? ........................................ 124 B. The Threats to Marine Biodiversity ............................... 126 II. OVEREXPLOITATION ..................................................................... 127 A. International Framework for Fisheries Management .................................................................... 129 1. Early Efforts at Fishery Management ............... 130 2. The 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea ................................................... 131 B. Regional Fishery Organizations and Agreements ........ 134 C. Additional International Agreements Protecting Marine Mammals, Birds and Other Wildlife................. 136 1. Marine Mammal Conventions .......................... 136 2. Protection of Migratory Birds ........................... 138 3. Conservation of Overexploited Wildlife .......... 140 D. Domestic Strategies for Conserving Marine Biodiversity Globally ...................................................... 141 1. Trade and Economic Measures ......................... 141 2. Direct Regulation ............................................... 143 III. ALTERATION OF THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT .......................... 144 A. Coastal Development ..................................................... -

Manual for Phytoplankton Sampling and Analysis in the Black Sea

Manual for Phytoplankton Sampling and Analysis in the Black Sea Dr. Snejana Moncheva Dr. Bill Parr Institute of Oceanology, Bulgarian UNDP-GEF Black Sea Ecosystem Academy of Sciences, Recovery Project Varna, 9000, Dolmabahce Sarayi, II. Hareket P.O.Box 152 Kosku 80680 Besiktas, Bulgaria Istanbul - TURKEY Updated June 2010 2 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Basic documents used............................................................................................... 1.2 Phytoplankton – definition and rationale .............................................................. 1.3 The main objectives of phytoplankton community analysis ........................... 1.4 Phytoplankton communities in the Black Sea ..................................................... 2. SAMPLING ................................................................................................................. 9 2.1 Site selection................................................................................................................. 2.2 Depth ............................................................................................................................... 2.3 Frequency and seasonality ....................................................................................... 2.4 Algal Blooms................................................................................................................. 2.4.1 Phytoplankton bloom detection -

Marine Protected Areas (Mpas) in Management 1 of Coral Reefs

ISRS BRIEFING PAPER 1 MARINE PROTECTED AREAS (MPAS) IN MANAGEMENT 1 OF CORAL REEFS SYNOPSIS Marine protected areas (MPAs) may stop all extractive uses, protect particular species or locally prohibit specific kinds of fishing. These areas may be established for reasons of conservation, tourism or fisheries management. This briefing paper discusses the potential uses of MPAs, factors that have affected their success and the conditions under which they are likely to be effective. ¾ MPAs are often established as a conservation tool, allowing protection of species sensitive to fishing and thus preserving intact ecosystems, their processes and biodiversity and ultimately their resilience to perturbations. ¾ Increases in charismatic species such as large groupers in MPAs combined with the perception that the reefs there are relatively pristine mean that MPAs can play a significant role in tourism. ¾ By reducing fishing mortality, effective MPAs have positive effects locally on abundances, biomass, sizes and reproductive outputs of many exploitable site- attached reef species. ¾ Because high biomass of focal species is sought but this is quickly depleted and is slow to recover, poaching is a problem in most reef MPAs. ¾ Target-species ‘spillover’ into fishing areas is likely occurring close to the MPA boundaries and benefits will often be related to MPA size. Evidence for MPAs acting as a source of larval export remains weak. ¾ The science of MPAs is at an early stage of its development and MPAs will rarely suffice alone to address the main objectives of fisheries management; concomitant control of effort and other measures are needed to reduce fishery impacts, sustain yields or help stocks to recover. -

EXTENDED COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS of PRESENT and FUTURE USE of INDONESIAN CORAL REEFS an Empirical Approach to Sustainable Management of Tropical Marine Resources

Aus dem Institut für Agrarökonomie der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel EXTENDED COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF PRESENT AND FUTURE USE OF INDONESIAN CORAL REEFS An Empirical Approach to Sustainable Management of Tropical Marine Resources Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Agrar-und Ernährungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Magister of Science Achmad Fahrudin aus Jakarta (Indonesien) Kiel, November 2003 Dekan : Prof. Dr. Friedhelm Taube Erster Berichterstatter : Prof. Dr. Christian Noell Zweiter Berichterstatter : Prof. Dr. Franciscus Colijn Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 06.11.2003 i Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Agrar- und Ernährungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel ii Zusammenfassung Korallen stellen einen wichtigen Faktor der indonesischen Wirtschaft dar. Im Vergleich zu anderen Ländern weisen die Korallenriffe Indonesiens die höchsten Schädigungen auf. Das zerstörende Fischen ist ein Hauptgrund für die Degradation der Korallenriffe in Indonesien, so dass das Gesamtsystem dieser Fangpraxis analysiert werden muss. Dazu wurden im Rahmen dieser Studie die Standortbedingungen der Korallen erfasst, die Hauptnutzungen mit ihren jeweiligen Auswirkungen und typischen Merkmale der Nutzungen bestimmt sowie die politische Haltung der gegenwärtigen Regierung gegenüber diesem Problemfeld untersucht. Die Feldarbeit wurde in der Zeit von März 2001 bis März 2002 an den Korallenstandorten Seribu Islands (Jakarta), Menjangan Island (Bali) und Gili Islands -

CORAL REEF DEGRADATION in the INDIAN OCEAN Status Report 2005

Coral Reef Degradation in the Indian Ocean Status Report 2005 Coral Reef Degradation in the Indian Ocean. The coastal ecosystem of the Indian Ocean includes environments such as mangroves, sea- Program Coordination grass beds and coral reefs. These habitats are some CORDIO Secretariat Coral Reef Degradation of the most productive and diverse environments Olof Lindén on the planet. They form an essential link in the David Souter Department of Biology and Environmental food webs that leads to fish and other seafood in the Indian Ocean Science providing food security to the local human University of Kalmar population. In addition coral reefs and mangrove 29 82 Kalmar, Sweden Status Report 2005 forests protect the coastal areas against erosion. (e-mail: [email protected], Unfortunately, due to a number of human activi- [email protected]) Editors: DAVID SOUTER & OLOF LINDÉN ties, these valuable environments are now being degraded at an alarming rate. The use of destruc- CORDIO East Africa Coordination Center David Obura tive fishing techniques on reefs, coral mining and P.O. Box 035 pollution are examples of some of these stresses Bamburi, Mombasa, Kenya from local sources on the coral reefs. Climate (e-mail: [email protected], change is another stress factor which is causing [email protected]) additional destruction of the reefs. CORDIO is a collaborative research and CORDIO South Asia Coordination Center development program involving expert groups in Dan Wilhelmsson (to 2004) Status Report 2005 countries of the Indian Ocean. The focus of Jerker Tamelander (from 2005) IUCN (World Conservation Union) CORDIO is to mitigate the widespread degrada- 53 Horton Place, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka tion of the coral reefs and other coastal eco- (e-mail: [email protected]) systems by supporting research, providing knowledge, creating awareness, and assist in CORDIO Indian Ocean Islands developing alternative livelihoods. -

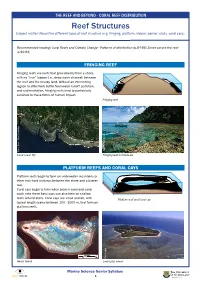

Reef Structures Subject Matter: Recall the Different Types of Reef Structure (E.G

THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures Subject matter: Recall the different types of reef structure (e.g. fringing, platform, ribbon, barrier, atolls, coral cays). Recommended reading: Coral Reefs and Climate Change - Patterns of distribution (p.84-85) Zones across the reef (p.92-94) FRINGING REEF Fringing reefs are reefs that grow directly from a shore, with no “true” lagoon (i.e., deep water channel) between the reef and the nearby land. Without an intervening lagoon to effectively buffer freshwater runoff, pollution, and sedimentation, fringing reefs tend to particularly sensitive to these forms of human impact. Fringing reef Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Planet Dove - Allen Coral Atlas Allen Coral Planet Dove - Coral coast, Fiji Fringing reef in Indonesia. PLATFORM REEFS AND CORAL CAYS Platform reefs begin to form on underwater mountains or other rock-hard outcrops between the shore and a barrier reef. Coral cays begin to form when broken coral and sand wash onto these flats; cays can also form on shallow reefs around atolls. Coral cays are small islands, with Platform reef and Coral cay typical length scales between 100 - 1000 m, that form on platform reefs, Dave Logan Heron Island Lady Elliot Island Marine Science Senior Syllabus 8 THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures BARRIER REEFS BARRIER REEFS are coral reefs roughly parallel to a RIBBON REEFS are a type of barrier reef and are unique shore and separated from it by a lagoon or other body of to Australia. The name relates to the elongated Reef water.The coral reef structure buffers shorelines against bodies starting to the north of Cairns, and finishing to the waves, storms, and floods, helping to prevent loss of life, east of Lizard Island.