Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

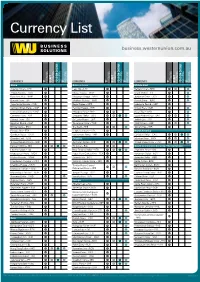

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Standard Settlement Instructions for Foreign Exchange, Money Market and Commercial Payments

Standard Settlement Instructions For Foreign Exchange, Money Market and Commercial Payments CURRENCY CORRESPONDENT BANK S.W.I.F.T ADDRESS Australian Dollar Westpac Banking Corporation WPACAU2S AUD Sydney, Australia Barbados Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia, Bridgetown NOCSBBBB BBD Barbados Bermudian Dollar The Bank of N. T. Butterfield & Son Ltd. BNTBBMHM BMD Hamilton, Bermuda Bahamian Dollar Scotiabank (Bahamas) Ltd. NOSCBSNS BSD Nassau, Bahamas Belize Dollar Scotiabank (Belize) Ltd., NOSCBZBS BZD Belize City, Belize Canadian Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCCATT CAD International Banking Division, Toronto Cyprus Pound Bank of Cyprus Public Company Ltd., BCYPCY2N010 CYP Nicosia, Cyrpus Czech Koruna Ceskolovenska Obchodni Banka A.S. CEKOCZPP CZK Prague Danish Krone Nordea Bank Danmark A/S NDEADKKK DKK Copenhagen, Denmark Euro Deutsche Bank AG DEUTDEFF EUR Frankfurt Fiji Dollar Wetspac Banking Corporation WPACFJFX FJD Suva, Fiji Guyana Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia, Georgetown, NOSCGYGE GYD Guyana Hong Kong Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCHKHH HKD Hong Kong Hungarian Forint MKB Bank ZRT MKKB HU HB HUF Indian Rupee The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCINBB INR Mumbai Indonesian Rupiah Standard Chartered Bank SCBLIDJX IDR Jakarta, Indonesia Israeli Sheqel Bank Hapaolim BM POALILIT ILS Tel Aviv Jamaican Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia Jamaica Ltd. NOSCBSNSKIN JMD Kingston, Jamaica Japanese Yen The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd. BOTKJPJT JPY Tokyo Cayman Islands Dollar Scotiabank and Trust (Cayman) Ltd. NOSCKYKX KYD Cayman Islands Malaysian -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Currency List

Americas & Caribbean | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ANG Netherland Antillean Guilder ARS Argentine Peso BBD Barbados Dollar BMD Bermudian Dollar BOB Bolivian Boliviano BRL Brazilian Real BSD Bahamian Dollar CAD Canadian Dollar CLP Chilean Peso CRC Costa Rica Colon DOP Dominican Peso GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal GYD Guyana Dollar HNL Honduran Lempira J MD J amaican Dollar KYD Cayman Islands MXN Mexican Peso NIO Nicaraguan Cordoba PEN Peruvian New Sol PYG Paraguay Guarani SRD Surinamese Dollar TTD Trinidad/Tobago Dollar USD US Dollar UYU Uruguay Peso XCD East Caribbean Dollar 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Europe | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ALL Albanian Lek BGN Bulgarian Lev CHF Swiss Franc CZK Czech Koruna DKK Danish Krone EUR Euro GBP Sterling Pound HRK Croatian Kuna HUF Hungarian Forint MDL Moldovan Leu NOK Norwegian Krone PLN Polish Zloty RON Romanian Leu RSD Serbian Dinar SEK Swedish Krona TRY Turkish Lira UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Middle East | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverabl Non-Deliverabl Special Symbol Capability e Forward e Forward requirements/ Restrictions AED Utd. Arab Emir. Dirham BHD Bahraini Dinar ILS Israeli New Shekel J OD J ordanian Dinar KWD Kuwaiti Dinar OMR Omani Rial QAR Qatar Rial SAR Saudi Riyal 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name*

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Afghanistan AFA Afghani Albania ALL Lek Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Amer Samoa USD US Dollar Andorra ADP Andorran Peseta Angola AON New Kwanza Anguilla XCD East Caribbean Dollar Antigua Barb XCD East Caribbean Dollar Argentina ARS Argentine Peso Armenia AMD Armeniam Dram Aruba AWG Aruban Guilder Australia AUD Australian Dollar Austria ATS Schilling Azerbaijan AZM Azerbaijanian Manat Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahrain BHD Bahraini Dinar Bangladesh BDT Taka Barbados BBD Barbados Dollar Belarus BYB Belarussian Ruble Belgium BEF Belgian Franc Belize BZD Belize Dollar Benin XOF CFA Franc Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Bhutan BTN Ngultrum Bolivia BOB Boliviano Botswana BWP Pula Br Ind Oc Tr USD US Dollar Br Virgin Is USD US Dollar Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Brunei Darsm BND Brunei Dollar Bulgaria BGN New Lev Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Côte dIvoire XOF CFA Franc Cambodia KHR Riel Cameroon XAF CFA Franc Canada CAD Canadian Dollar Cape Verde CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cayman Is KYD Cayman Islands Dollar Cent Afr Rep XAF CFA Franc Chad XAF CFA Franc Channel Is GBP Pound Sterling Chile CLP Chilean Peso China CNY Yuan Renminbi China, Macao MOP Pataca China,H.Kong HKD Hong Kong Dollar China,Taiwan TWD New Taiwan Dollar Christmas Is AUD Australian Dollar Cocos Is AUD Australian Dollar Colombia COP Colombian Peso Comoros KMF Comoro Franc FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Congo Dem R CDF Franc Congolais Congo Rep XAF CFA Franc Cook Is NZD New Zealand Dollar Costa Rica -

Data Delivery (26.01) Descriptive Update and Master Files

DATA DELIVERY SERVICE CF2/MQ TRANSMISSION GUIDES 26.01 DESCRIPTIVE UPDATE AND MASTER FILES / INTERNATIONAL MESSAGES / AGENT UPDATE AND MASTER MESSAGES Version 2.8 SEPTEMBER 15, 2020 DTCC Public (White) © 2020 DTCC. All rights reserved. DTCC, DTCC (Stylized), ADVANCING FINANCIAL MARKETS. TOGETHER, and the Interlocker graphic are registered and unregistered trademarks of The Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation. The services described herein are provided under the “DTCC” brand name by certain affiliates of The Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (“DTCC”). DTCC itself does not provide such services. Each of these affiliates is a separate legal entity, subject to the laws and regulations of the particular country or countries in which such entity operates. Please see www.dtcc.com for more information on DTCC, its affiliates and the services they offer. Doc Date: September 15, 2020 Publication Code: MAS102 Service: Data Delivery Service Title: 26.01 Descriptive Update and Master Files / International Messages / Agent Update And Master Messages 2 DTCC Public (White) Document Version This document was written by DTCC Data Services in conjunction with the Business Systems and Documentation group, a group within the Customer Training and Information Products department. The following table details the releases of this document and the changes incorporated into each release. This document contains the first release of specifications, which will be updated and modified when additional phases are completed and/or new features and/or information is added. Should you have any questions regarding this document or its contents, please contact [email protected]. Table 1: Document Change History Version Date Summary 1.0 11/24/00-Draft First draft of document. -

Currencies of the World

The World Trade Press Guide to Currencies of the World Currency, Sub-Currency & Symbol Tables by Country, Currency, ISO Alpha Code, and ISO Numeric Code € € € € ¥ ¥ ¥ ¥ $ $ $ $ £ £ £ £ Professional Industry Report 2 World Trade Press Currencies and Sub-Currencies Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies of the World of the World World Trade Press Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s 800 Lindberg Lane, Suite 190 Petaluma, California 94952 USA Tel: +1 (707) 778-1124 x 3 Introduction . 3 Fax: +1 (707) 778-1329 Currencies of the World www.WorldTradePress.com BY COUNTRY . 4 [email protected] Currencies of the World Copyright Notice BY CURRENCY . 12 World Trade Press Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies Currencies of the World of the World © Copyright 2000-2008 by World Trade Press. BY ISO ALPHA CODE . 20 All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the express written permission of the Currencies of the World copyright holder is unlawful. Requests for permissions and/or BY ISO NUMERIC CODE . 28 translation or electronic rights should be addressed to “Pub- lisher” at the above address. Additional Copyright Notice(s) All illustrations in this guide were custom developed by, and are proprietary to, World Trade Press. World Trade Press Web URLs www.WorldTradePress.com (main Website: world-class books, maps, reports, and e-con- tent for international trade and logistics) www.BestCountryReports.com (world’s most comprehensive downloadable reports on cul- ture, communications, travel, business, trade, marketing, -

IATA Rates of Exchange (IROE) ISO Local Deci ISO Code Other Lim Country Currency Name Code from NUC Curr

Page 1 Prepared by A. Khreis IATA Rates of Exchange (IROE) ISO Local Deci ISO Code Other Lim Country Currency Name Code From NUC Curr. mal Notes Numeric Charges Alpha Fares Units Afghanistan US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 + Afghanistan Afghani AFN 971 49.500000 1 1 0 2, 8 Albania euro EUR 978 0.810635 1 0.01 2 + Albania Lek ALL 8 NA 1 1 0 22 + Algeria Algerian Dinar DZD 12 86.906400 10 1 0 American Samoa US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 5 Angola US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 5 + Angola Kwanza AOA 973 101.834000 1 1 0 2, 8 Anguilla US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 5 Anguilla East Caribbean Dollar XCD 951 2.700000 1 0.1 2 2,5 Antigua Barbuda East Caribbean Dollar XCD 951 2.700000 1 0.1 2 2 Antigua Barbuda US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 5 Argentina US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 5 + Argentina Argentine Peso ARS 32 8.546600 1 0.1 2 1, 2, 5, Armenia euro EUR 978 0.810635 1 0.01 2 + Armenia Armenian Dram AMD 51 452.500000 1 1 0 8, 22 Aruba Aruban Guilder AWG 533 1.790000 1 1 0 Australia Australian Dollar AUD 36 1.199437 1 0.1 2 8, 17 Austria euro EUR 978 0.810635 1 0.01 2 + Azerbaijan Azerbaijanian Manat AZN 944 0.783840 0.01 0.1 2 8, 22 Azerbaijan euro EUR 978 0.810635 1 0.01 2 Bahamas US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 5 Bahamas Bahamian Dollar BSD 44 NA 1 0.1 2 2 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar BHD 48 0.376100 1 0.1 3 Bangladesh US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 5 + Bangladesh Taka BDT 50 77.311000 1 1 0 2,19 Barbados US Dollar USD 840 1.000000 1 0.1 2 5 + Barbados Barbados Dollar BBD 52 NA 1 0.1 2 2 + Belarus Belarussian Ruble -

PDF External Sector Statistics ISO Country Codes

External Sector Statistics (ESS) System - Submission of International Transactions Page 285 of 300 and External Position Information APPENDIX 8 STANDARD CODES Appendix 8(a) List of Country and Currency Codes ISO Country and Currency Codes* Country Code Currency Code AFGHANISTAN AF Afghani AFN ÅLAND ISLANDS AX Euro EUR ALBANIA AL Lek ALL ALGERIA DZ Algerian Dinar DZD AMERICAN SAMOA AS US Dollar USD ANDORRA AD Euro EUR ANGOLA AO Kwanza AOA ANGUILLA AI East Caribbean Dollar XCD ANTARCTICA AQ No universal currency ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA AG East Caribbean Dollar XCD ARGENTINA AR Argentine Peso ARS ARMENIA AM Armenian Dram AMD ARUBA AW Aruban Florin AWG AUSTRALIA AU Australian Dollar AUD AUSTRIA AT Euro EUR AZERBAIJAN AZ Azerbaijanian Manat AZN BAHAMAS BS Bahamian Dollar BSD BAHRAIN BH Bahraini Dinar BHD BANGLADESH BD Taka BDT BARBADOS BB Barbados Dollar BBD BELARUS BY Belarussian Ruble BYR BELGIUM BE Euro EUR BELIZE BZ Belize Dollar BZD BENIN BJ CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BERMUDA BM Bermudian Dollar BMD BHUTAN BT Ngultrum BTN BHUTAN BT Indian Rupee INR BOLIVIA, PLURINATIONAL STATE OF BO Boliviano BOB BOLIVIA, PLURINATIONAL STATE OF BO Mvdol BOV BONAIRE, SINT EUSTATIUS AND SABA BQ US Dollar USD BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BA Convertible Mark BAM BOTSWANA BW Pula BWP BOUVET ISLAND BV Norwegian Krone NOK BRAZIL BR Brazilian Real BRL BRITISH INDIAN OCEAN TERRITORY IO US Dollar USD BRUNEI DARUSSALAM BN Brunei Dollar BND BULGARIA BG Bulgarian Lev BGN BURKINA FASO BF CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BURUNDI BI Burundi Franc BIF CAMBODIA KH Riel KHR CAMEROON CM CFA Franc BEAC -

Bond Type Codes

Customs and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix B Valid Codes This appendix lists valid Automated Commercial System (ACS) codes. Valid codes to be used in ACS are presented in the following order: Bond Type Codes International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Country and Currency Codes District/Port Codes These codes have been removed from this appendix. Refer to the Extract Reference File Chapter of this document, Record Identifier F101 for information on querying District/Port Codes. Entry Type Codes Missing Document Codes Mode of Transportation Codes Related Document Identifiers Shipping/Packaging Unit Codes IRS Excise Tax/Fee Codes Other Government Agency Codes Equipment Description Codes Amendment Codes Amendment 5 – March 2004 Appendix B B- 1 Customs and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Bond Type Codes This section lists valid bond types for each entry type. For a description of the entry type codes, refer to the Entry Type Codes section in this chapter. Bond Type Codes Entry Types Government Non-Government Importer Importer 01 8, 9 8, 9 02 8, 9 8, 9 03 8, 9 8, 9 04 0 0 05 8, 9 8, 9 06 8, 9 8, 9 07 8, 9 8, 9 11 0, 8, 9 0, 8, 9 12 0, 8 0, 8 21 8, 9 8, 9 22 8, 9 8, 9 41 8, 9 8, 9 42 8, 9 8, 9 43 8, 9 8, 9 51 8, 9, 0 8, 9 52 8, 9, 0 8, 9 53 8, 9, 0 8, 9 Valid bond type codes are: 0 = No bond required 8 = Continuous bond 9 = Single transaction bond Note: If the bond type is 0 for entry types 51, 52 and 53, the surety code 999 is required.