Outselling Beatles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Album Reviews

Album Reviews I’ve written over 150 album reviews as a volunteer for CHIRPRadio.org. Here are some examples, in alphabetical order: Caetano Veloso Caetano Veloso (A Little More Blue) Polygram / 1971 Brazilian Caetano Veloso’s third self-titled album was recorded in England while in exile after being branded ‘subversive’ by the Brazilian government. Under colorful plumes of psychedelic folk, these songs are cryptic stories of an outsider and traveller, recalling both the wonder of new lands and the oppressiveness of the old. The whole album is recommended, but gems include the autobiographical “A Little More Blue” with it’s Brazilian jazz acoustic guitar, the airy flute and warm chorus of “London, London” and the somber Baroque folk of “In the Hot Sun of a Christmas Day” tells the story of tragedy told with jazzy baroque undertones of “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen.” The Clash London Calling Epic / 1979 London Calling, considered one of the greatest rock & roll albums ever recorded, is far from a straightforward: punk, reggae, ska, R&B and rockabilly all have tickets to this show of force that’s both pop and revolutionary. The title track opens with a blistering rallying cry of ska guitar and apocalypse. The post-disco “Clampdown” is a template for the next decade, a perfect mix of gloss and message. “The Guns of Brixton” is reggae-punk in that order, with rocksteady riffs and rock drums creating an intense portrait of defiance. “Train in Vain” is a harmonica puffing, Top 40 gem that stands at the crossroads of punk and rock n’ roll. -

Coast Capers

= Coast Capers ` By JACK DEVANEY Sonny and Cher were honored "Soulin'," has been set by Mo- WHERE IT'S AT at a cocktail party for local and town to do likewise for the new foreign press on the eve of album by the Supremes. their departure for their Euro- Mel Carter set to headline Amy Records is thrilled with the reaction on "I'm Your pean tour . LuLu Porter three Southwest concert dates Puppet," James & Bobby Purify, Bell. WVON made it the Pick opens at the Little Club this Sept. 9, 10 and 11 ... Metric's of the Week and so did WAMO, Pittsburgh. The reaction to Tuesday night . John Fish- Mike Gould and Ernie Farrell "Fannie Mae," Mighty Sam, is also tremendous, according to er's Current label out with a are having mucho success with Larry Uttal and Fred DeMann. new one-"Let's Talk About "I Chose to Sing the Blues," Instant Smash: "Said I Wasn't Gonna Tell Nobody" by Sam Girls" by the Tongues of Truth penned by Jimmy Holiday and and Dave. The driving 'Boogaloo' beat is a natural for what's .. Al Hirt will make a guest Ray Charles and recorded by happening in today's market! ... Dr. Fat Daddy did it again. appearance in the film, "What Charles ... Capitol held a jam- He broke a record in Baltimore all by himself : "I Need a Am I Bid ?," to be released this packed press conference for the Girl," Righteous Brothers, Moonglow. We kept telling you fall. Movie stars LeRoy Van Beatles prior to their KRLA- this was a hit side, and Paul proved it. -

Rock Around the Clock”: Rock ’N’ Roll, 1954–1959

CHAPTER EIGHT: “ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK”: ROCK ’N’ ROLL, 1954–1959 Chapter Outline I. Rock ’n’ Roll, 1954–1959 A. The advent of rock ’n’ roll during the mid-1950s brought about enormous changes in American popular music. B. Styles previously considered on the margins of mainstream popular music were infiltrating the center and eventually came to dominate it. C. R&B and country music recordings were no longer geared toward a specialized market. 1. Began to be heard on mainstream pop radio 2. Could be purchased nationwide in music stores that catered to the general public D. Misconceptions 1. It is important to not mythologize or endorse common misconceptions about the emergence of rock ’n’ roll. a) Rock ’n’ roll was not a new style of music or even any single style of music. CHAPTER EIGHT: “ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK”: ROCK ’N’ ROLL, 1954–1959 b) The era of rock ’n’ roll was not the first time music was written specifically to appeal to young people. c) Rock ’n’ roll was not the first American music to bring black and white pop styles into close interaction. d) “Rock ’n’ roll” was a designation that was introduced as a commercial and marketing term for the purpose of identifying a new target for music products. II. The Rise of Rhythm & Blues and the Teenage Market A. The target audience for rock ’n’ roll during the 1950s consisted of baby boomers, Americans born after World War II. 1. Relatively young target audience 2. An audience that shared some specific important characteristics of group cultural identity: a) Recovering from the trauma of World War II—return to normalcy b) Growing up in the relative economic stability and prosperity of the 1950s yet under the threat of atomic war between the United States and the USSR CHAPTER EIGHT: “ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK”: ROCK ’N’ ROLL, 1954–1959 c) The first generation to grow up with television—a new outlet for instantaneous nationwide distribution of music d) The Cold War with the Soviet Union was in full swing and fostered the anticommunist movement in the United States. -

MUS 125 SYLLABUS(Spring 2016)

SYLLABUS MUS 125 HISTORY OF ROCK MUSIC - 3 CREDIT HOURS WESTERN NEVADA COLLEGE Monday and Wednesday at 11:00pm to 12:15pm First class: January 25, 2016 Final class and final exam: May 19, 2016 Last day to drop this class and receive a “W” is: April 01, 2016 Instructor: John Shipley, my email is: [email protected] I do not have an office at WNC to meet students in, but you can text or call my cell phone at 775/219-9434 and I will make time to assist you with anything pertaining to this class. Cell Phones And Other Electronic Communication Devices: As a courtesy to others, please turn off and store all cell phones and other electronic communications devices when in this class. Also, if you use a laptop to take notes in this class, please make sure the noise emitted by the keyboard does not disturb other students. *** NO CLASS IS TO BE RECORDED, BY ANY MEANS, WITHOUT THE PRIOR APPROVAL OF YOUR INSTRUCTOR. *** Required Materials: 1) Rock 'n Roll, Origins and Innovators by Timothy Jones and Jim McIntosh 2) A Pandora Apple Music or Spotify account or access to the music presented in class, i.e. your own or friend’s record/CD collection. Another resource is YouTube.com, much of the music used in this class can be found on that website. Remember downloading audio files from file sharing websites is illegal and is theft of the songwriters of this great music. COURSE DESCRIPTION: The History of Rock Music is open to all students at WNC with no pre-requisites. -

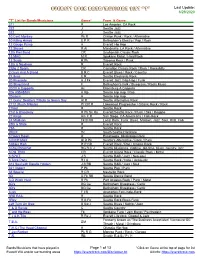

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "GH"

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "G-H" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "G-H" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre a Gamble in the Litter F I Mukilteo Minimalist / Folk / Indie G2 RB S H IL R&B/Soul / rap / hip hop Gabe Mintz I R A Seattle Indie / Rock / Acoustic Gabe Rozzell/Decency F C Gabe Rozzell and The Decency Portland Folk / Country Gabriel Kahane P Brooklyn, NY Pop Gabriel Mintz I Seattle Indie Gabriel Teodros H Rp S S Seattle/Brooklyn NY Hip Hop / Rap / Soul Gabriel The marine I Long Island Indie Gabriel WolfChild SS F A Olympia Singer Songwriter / folk / Acoustic Gaby Moreno Al S A North Hollywood, CA Alternative / Soul / Acoustic Gackstatter R Fk Seattle Rock / Funk Gadjo Gypsies J Sw A Bellingham Jazz / Swing / Acoustic GadZooks P Pk Seattle Pop Pk Gaelic Storm W Ce A R Nashville, TN World / Celtic / Acoustic Rock Gail Pettis J Sw Seattle Jazz / Swing Galapagos Band Pr R Ex Bellingham progressive/experimental rock Galaxy R Seattle Rock Gallery of Souls CR Lake Stevens Rock / Powerpop / Classic Rock Gallowglass Ce F A Bellingham traditional folk and Irish tunes Gallowmaker DM Pk Bellingham Deathrock/Surf Punk Gallows Hymn Pr F M Bellingham Progressive Folk Metal Gallus Brothers C B Bellingham's Country / Blues / Death Metal Galperin R New York City bossa nova rock GAMBLERS MARK Sf Ry El Monte CA Psychobilly / Rockabilly / Surf Games Of Slaughter M Shelton Death Metal / Metal GammaJet Al R Seattle Alternative / Rock gannGGreen H RB Kent Hip Hop / R&B Garage Heroes B G R Poulsbo Blues / Garage / Rock Garage Voice I R Seattle's Indie -

The Liverpool Packet

THE LIVERPOOL PACKET ]ANET E. MULLINS F the matters recorded concerning the town of Liverpool, none O compares either in point of vital interest in its time or in challenge to the imagination with that of privateering. Almost from the time of its settlement by the English this activity made its influence felt, slightly in earlier years, acutely from 1776 to 1815, in a diminishing degree since, ripples from the centre of agitation of the War of 1812 not yet having lost themselves on the shores of time. The word "privateering" suggests various things to various people; to some, a questionable mode of acquiring wealth; to others, a legalized method of harassing an enemy; to this one, piracy; to that, patriotism. The perspective afforded by time, contemporary history and newspaper files, especially those of the enemy, letters, diaries, log-books, all provide the means to de termine whether the Maritimes were justified or not in resorting to this mode of warfare. Privateers were owned, armed and equipped by private citizens and used as defenders of the coast, intelligence craft, commerce destroyers. The Liverpool privateersmen were of excellent stock, all leading citizens of their community, well and favorably known to British naval officers of the time. When the wars were over, many filled positions of honour as members of parliament, judges, ship-owners, merchants. The crews, mostly fishermen, were picked from volun teers, the success of a cruise depending on each man's ability in seamanship and his skill in the use of naval weapons. None were on wages. All fought on a share system. -

Introduction to Rock Music

Introduction to Rock Music Rock ‘n’ Roll Explodes! In the beginning… There is absolutely no Some Examples: agreement as to when Bill Haley Rock ‘n’ Roll began. Crazy Man Crazy Why? Explain…! The Dominoes Development over Sixty Minute Man time. Evolutionary process. Li’l Son Jackson Rockin’ and Rollin’ Definition: What do you define as Rock Wynonie Harris ‘n’ Roll. Good Rockin’ Rhythm and Tonight Blues? Musical Genre Sexual metaphor Cultural Diversity The Roots of Rock ‘n’ Roll •• R&B + C&W = R&R •• In addition to race, ethnicity, –– What is wrong with this musical culture, issues of class statement? and gender must be looked at. •• “The clichclichèè is that rock & roll •• Fully erupted into the was a melding of country music mainstream market in 1956. and blues, and if you are talking Had an “integration” type about Chuck Berry & Elvis phenomenon. The rock charts Presley, the description, though were more racially equal than at simplistic, does fit. But the any other time. black innerinner--citycity vocalvocal--groupgroup –– Much of early rock ‘n’ roll was sound…had little to do with based on predominantly either blues or country music in African American forms that their purer forms.” became more mainstream –– What does this mean? The Gender Game Early rock ‘n’ roll had a large effect on the success of women in the music industry? Why do you think that is? Only an average of 2 women in the top 25 records or songs each year. Rock ‘n’ Roll had a definite male sexuality at the beginning. Women did not sing, they were sung about. -

Artist Title Year Master Label Serial Number Pressed by Country Stereo

Artist Title Year Master Label Serial Number Pressed By Country Stereo-Mono Disk Condition Cover Condition Comments Abba Ring Ring 1973 RCA SL102323 AUST Stereo G slight cover wear First Adam Faith Adam 1960 Parlophone PMC-1128 UK Stereo G slight cover wear First Adventurers, The Can’ stop twisting 1966 Coronet KLL-1712 Philips NZ Stereo G G First + only Affection Collection, The The Affection Collection 1968 Evolution 2007 USA Stereo G G First + only Alice Cooper Pretties for you 1969 Straight WB-1840 Warner Brothers USA G G First-GATE FOLD Allisons, The Are you sure? 1961 Fontana STFL-558 UK Stereo G G First + only Ambrose Slade Ballzy 1969 Fontana SRF-67598 USA Stereo G G First Amen Corner Round 1968 Decca SMLM-1021 HMV NZ Stereo G G First American Breed American Breed 1967 Quality ACTA-38002 Canada Stereo G G 2 small punch holes on disc First Allied American Eagle American Eagle 1970 MCA MAP-S-4217 NZ Stereo G Slight damage on bottom back flap First+ only International Angels, The My Boyfriend's Back 1963 Philips BL-14542 Philips NZ Mono G Tape on back edge-small tear on opening Second Animals, The The Animals 1964 Columbia 33-MSX-6057 HMV NZ Mono BAD BAD Gap filler only Annette Annette 1959 Disney WDL-3301 NZ Stereo F+ Slight wear on back cover Second Aorta Aorta 1969 Columbia CS-9785 Canada Stereo G G First + only GATE FOLD Apollo 11 We have landed on the moon 1969 Capitol SREG-326 HMV NZ Stereo F+ Name and mark on back First + only Apple Pie Motherhood Band, The The Apple Pie Motherhood Band 1968 Atlantic SD-8189 USA Stereo G Remains -

“Nothing Is Beatleproof!” in What Context?

Thesis, 15 hec Spring 2010 Master in Communication Applied Information technology / SSKKII University of Gothenburg Report No. 2010: 098 ISSN: 1651-4769 “Nothing is Beatleproof!” In what context? The communicationArt and the artist'sbetween image the Beatlesas communication and their audience, and the importance of context in the formation of the band’s image Author: EIRINI DANAI VLACHOU Supervisor: BILYANA MARTINOVSKI, PhD EIRINI DANAI VLACHOU “Nothing is Beatleproof!”* In what context? Art and the artist's image as communication ABSTRACT Art is often defined as a process of creation guided by artist’s intention. However, artwork as a means of expression is also a communicative medium. Does context and audience influence artwork and identity of artists? How? Can one define an artwork as a co-design between artist and context, including the audience? What is the role of communication in this process? The purpose of the thesis is to explore the idea of art as a communicative co-design process by studying the relation between the popular music band Beatles and its context. Is their image or identity a result of a marketing intention or a co-design, which occurred between the band and their audience and colleagues? The band’s artistic approaches, patterns and strategies are viewed from a communi- cation perspective. Answers to the above questions are found in communication theories related to cre- ative processes, production and the media, studies in aesthetic theories and popular culture, and examples of communication between the band and its audience as well as between the band and other artists. The present study finds that interaction with audience had a profound effect on the Beatles’ art and image. -

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO -

Study Guide for Teachers

Study Guide for Teachers RockRoots A History of American Pop Music Presented by Young Audiences New Jersey & Eastern PA (866) 500-9265 www.yanjep.org ABOUT THE PROGRAM BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR STUDENTS Take a historical, political, and geographical riff through American pop music with this unique live It's much more informative than a rock concert or celebration of the history of rock & roll. From a TV program—but it's much more colorful than African rhythms, Delta blues, swing, R&B, and your average history lesson! RockRoots takes country through Elvis, Motown, the Beatles, you on a historical, geographic, and political tour Hendrix, disco, and world beat, four talented of the United States as it traces the evolution of musicians play with authority and joy while American pop music and rock & roll from its early sharing the tremendous educational and musical days to the music we hear today. power of this uniquely American cultural history. After a spirited rendition of Chuck Berry's classic, RockRoots has been bringing the rich history of "Rock 'n' Roll Music," the musical journey begins American roots music and rock & roll (and the with the ethnic music early immigrants brought to great experience of live music) to thousands of America. It continues through Delta blues, kids and teachers for more than 25 years. ragtime, Dixieland, jazz, big band music, rhythm & blues, country, and rockabilly—and finally to rock & roll and the current musical scene. The LEARNING GOALS journey ends with an original RockRoots rap! • To present the diverse elements of rock & roll Ensemble members demonstrate each history, from its rural beginning to the latest in technology, and to show how social, historical, instrument, explaining how it evolved and how all and political events have shaped popular music the instruments work in an ensemble. -

Episode 2 Rock Music with an Attitude 1OVERVIEW Rock Music Has Been One of the Driving Forc- Es of Youth Culture Since the 1950’S

Unit 4 Music Styles Episode 2 Rock Music with an attitude 1OVERVIEW Rock music has been one of the driving forc- es of youth culture since the 1950’s. Expres- sive and emotional, rock is music with an exclamation point! To express their outrage that a local park is going to be turned into a mega-store, the band takes up Quaver’s chal- lenge to express themselves through rock music. While they work on their song in the studio, Quaver and Repairman dive into the genre by looking at its history, instrumenta- tion, sound, form, lyrics, and feel. LESSON OBJECTIVES Students will learn: • Rock songs have a number of basic elements: a rock drum rhythm, three simple chords, a repeated lyric about something you care about, verses (A), and a chorus (B). • Rock uses microphones and amplified instruments so music is louder and reaches a bigger audience. • Rock bands commonly employ: a lead singer, drummer, electric guitarist or two, and an electric bass player. • Rock music has a strong, heavily accented, driving meter of 4. • Rock music has developed into many separate rock styles including punk, grunge, heavy metal, pop rock, pop, folk rock, and country rock. Vocabulary A section Chorus B section Lyrics Chords Amplifier Verse © Quaver’s Marvelous World of Music • 2-1 Unit 4 Music Styles MUSIC STANDARDS IN LESSON 1: Singing alone and with others* 2: Playing instruments 4: Composing and arranging music* 6: Listening to, analyzing, and describing music 7: Evaluating music and music performance 8: Understanding the relationship between music and the other arts 9: Understanding music in relation to history, style, and culture Complete details at QuaverMusic.com Key Scenes Music What they teach Standard 1 Paving a park to put up a The themes of rock music are often about life and per- 9 parking lot sonal experience.