The Llandovery Deep Place Study: a Pathway for Future Generations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vebraalto.Com

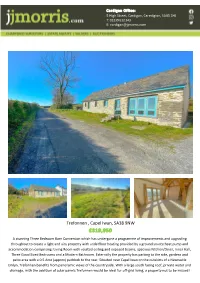

Cardigan Office: 5 High Street, Cardigan, Ceredigion, SA43 1HJ T: 01239 612 343 E: [email protected] Trefonnen , Capel Iwan, SA38 9NW £319,950 A stunning Three Bedroom Barn Conversion which has undergone a programme of improvements and upgrading throughout to create a light and airy property with underfloor heating provided by a ground source heat pump and accommodation comprising: Living Room with vaulted ceiling and exposed beams, spacious Kitchen/Diner, Inner Hall, Three Good Sized Bedrooms and a Modern Bathroom. Externally the property has parking to the side, gardens and patio area with a 0.5 Acre (approx) paddock to the rear. Situated near Capel Iwan on the outskirts of a Newcastle Emlyn, Trefonnen benefits from panoramic views of the countryside. With a large south facing roof, private water and drainage, with the addition of solar panels Trefonnen would be ideal for off‐grid living, a property not to be missed! Situation Bedroom 3 7'9" x 6'11" (2.37 x 2.12) Set some 2.5 miles from the rural village of Capel Iwan and 3.0 miles away from the market town of Newcastle Emlyn, with Carmarthen only 15.5 miles away. Newcastle Emlyn is a quaint market town dating back to the 13th Century. Straddling the two counties of Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire, Newcastle Emlyn town lies in Carmarthenshire and Adpar on the outskirts lies in Ceredigion divided by the River Teifi. The town offers residents and tourists a range of amenities include a Castle, supermarkets, restaurants and coffee shops, Post Office, a primary and secondary school, swimming pool, health centre, leisure centre, theatre, several public houses and many independent shops. -

Llanboidy Whitland

Wildlife in your Ward Wildlife in your Ward – Llanboidy-Whitland The Carmarthenshire Nature unmapped. There is always range of ecosystem services, Partnership has produced this more to find out. e.g. agricultural products, profile to highlight some of the Wildlife and our natural pollinators, timber, drinking wildlife, habitats, and environment reflect local water, regulation of floods and important sites in your local culture and past human soil erosion, carbon storage area. activity. We see this in the field and recreation and inspiration. Carmarthenshire is justly and hedgerow patterns in our Find out more at: celebrated for the variety agricultural landscapes, and in https://bit.ly/3u12Nvp within its natural environment, areas previously dominated by from the uplands in the north- industry where, today, new We hope it you will find this east of the county to our habitats develop on abandoned profile interesting and that it magnificent coastline. land. And our farm, house and might encourage you to Every ward contributes to the street names provide clues to explore your local area and rich and varied network of the history of our natural record what you see. There are wildlife habitats that make up environment. links in the profile that will help the county, whether that be The mosaic of habitats in you to find out more and take woodlands, grasslands Llanboidy-Whitland make up action locally. hedgerows, rivers or gardens. an ecological network. If these Thank you to all those in There are still gaps in our habitats are well managed, Llanboidy-Whitland wards who knowledge about are well connected and are have already sent information Carmarthenshire’s natural sufficiently extensive, they will and photos. -

Chapman, 2013) Anglesey Bridge of Boats Documentary and Historical (Menai and Anglesey) Research (Chapman, 2013)

MEYSYDD BRWYDRO HANESYDDOL HISTORIC BATTLEFIELDS IN WALES YNG NGHYMRU The following report, commissioned by Mae’r adroddiad canlynol, a gomisiynwyd the Welsh Battlefields Steering Group and gan Grŵp Llywio Meysydd Brwydro Cymru funded by Welsh Government, forms part ac a ariennir gan Lywodraeth Cymru, yn of a phased programme of investigation ffurfio rhan o raglen archwilio fesul cam i undertaken to inform the consideration of daflu goleuni ar yr ystyriaeth o Gofrestr a Register or Inventory of Historic neu Restr o Feysydd Brwydro Hanesyddol Battlefields in Wales. Work on this began yng Nghymru. Dechreuwyd gweithio ar in December 2007 under the direction of hyn ym mis Rhagfyr 2007 dan the Welsh Government’sHistoric gyfarwyddyd Cadw, gwasanaeth Environment Service (Cadw), and followed amgylchedd hanesyddol Llywodraeth the completion of a Royal Commission on Cymru, ac yr oedd yn dilyn cwblhau the Ancient and Historical Monuments of prosiect gan Gomisiwn Brenhinol Wales (RCAHMW) project to determine Henebion Cymru (RCAHMW) i bennu pa which battlefields in Wales might be feysydd brwydro yng Nghymru a allai fod suitable for depiction on Ordnance Survey yn addas i’w nodi ar fapiau’r Arolwg mapping. The Battlefields Steering Group Ordnans. Sefydlwyd y Grŵp Llywio was established, drawing its membership Meysydd Brwydro, yn cynnwys aelodau o from Cadw, RCAHMW and National Cadw, Comisiwn Brenhinol Henebion Museum Wales, and between 2009 and Cymru ac Amgueddfa Genedlaethol 2014 research on 47 battles and sieges Cymru, a rhwng 2009 a 2014 comisiynwyd was commissioned. This principally ymchwil ar 47 o frwydrau a gwarchaeau. comprised documentary and historical Mae hyn yn bennaf yn cynnwys ymchwil research, and in 10 cases both non- ddogfennol a hanesyddol, ac mewn 10 invasive and invasive fieldwork. -

WHITLAND WARD: ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE Policy Research and Information Section, Carmarthenshire County Council, May 2021

WHITLAND WARD: ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE Policy Research and Information Section, Carmarthenshire County Council, May 2021 Councillors (Electoral Vote 2017): Sue Allen (Independent). Turnout = 49.05% Electorate (April 2021): 1,849 Population: 2,406 (2019 Mid Year Population Estimates, ONS) Welsh Assembly and UK Parliamentary Constituency: Carmarthenshire West & Pembrokeshire © Hawlfraint y Goron a hawliau cronfa ddata 2017 Arolwg Ordnans 100023377 © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100023377 Location: Approximately 23km from Carmarthen Town Area: 22.34km2 Population Density: 108 people per km2 Population Change: 2011-2019: +134 (+5.9%) POPULATION STATISTICS 2019 Mid Year Population Estimates Age Whitland Whitland Carmarthenshire Structure Population % % Aged: 0-4 101 4.2 5.0 5-14 267 11.1 11.5 15-24 248 10.3 10.2 25-44 523 21.7 21.6 45-64 693 28.8 28.0 65-74 263 10.9 11.9 75+ 311 12.9 11.9 Total 2,406 100 100 Source: aggregated lower Super Output Area (LSOA) Small Area Population Estimates, 2019, Office for National Statistics (ONS) 16th lowest ward population in Carmarthenshire, and 26th lowest population density. Highest proportion of people over 45. Lower proportion of people with limiting long term illness. Lower proportion of Welsh Speakers than the Carmarthenshire average. 2011 Census Data Population: Key Facts Whitland Whitland % Carmarthenshire People: born in Wales 1585 69.8 76.0 born outside UK 69 3.1 4.1 in non-white ethnic groups 40 1.8 1.9 with limiting long-term illness 474 20.8 25.4 with no -

Two County Economic Study for Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire

OCTOBER 2019 Two County Economic Study for Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire Appendix A Literature Review Final Issue A Two County Economic Study for Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire Appendix A Literature Review Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Overview 1 2 National Objectives 2 2.1 Overview 2 2.2 National Development Framework (2019) 2 2.3 Taking Wales Forward (2016-2021) 3 2.4 Prosperity for All: The National Strategy and its Economic Action Plan (2017) 4 2.5 Planning Policy Wales, Edition 10 (2018) 6 3 Regional Objectives 8 3.1 Overview 8 3.2 Enterprise Zones: Haven Waterway 8 3.3 Swansea Bay City Deal 10 3.4 Adjacent to the Larger than Local Area 13 4 Local Context 15 4.1 Overview 15 4.2 Pembrokeshire Local Development Plan 15 4.3 Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 23 4.4 Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority Local Development Plan 30 4.5 Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan 32 4.6 Brecon Beacons National Park LDP2 33 4.7 Conclusions 34 5 Other Relevant Strategy Documents 36 5.1 Overview 36 5.2 Other Relevant National Strategy Documents 36 5.3 Other Relevant CCC documents 36 5.4 Other Relevant Pembrokeshire Documents 37 5.5 Other Relevant Initiatives/ Sources of Funding 39 6 Implications of the Literature Review 41 6.1 Overview 41 6.2 Key Definitions 41 6.3 Areas for Further Consideration 43 | Issue | 18 October 2019 \\GLOBAL\EUROPE\CARDIFF\JOBS\268000\268379-00\4 INTERNAL PROJECT DATA\4-50 REPORTS\10. FINAL REPORTING\2019.10.24 APPENDIX A FINAL ISSUE DOCUMENT REVIEW.DOCX A Two County Economic -

Cyngor Y Gymuned Llanfihangel Rhos-Y-Corn Community Council Minutes of Meeting Held at Brechfa Church Hall 6Th September 2018 at 8.00 P.M

Page 1 of 4 CYNGOR Y GYMUNED LLANFIHANGEL RHOS-Y-CORN COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES OF MEETING HELD AT BRECHFA CHURCH HALL 6TH SEPTEMBER 2018 AT 8.00 P.M. COUNCILLOR’S PRESENT:- Cllr. D. Daniels (Chair); Cllr. E. George; Cllr. E. Jones; Cllr. W. Richards; Cllr. R. Sisto; Cllr. A. Tattersall; Cllr. P. Wilson; County Cllr. Mansel Charles and the clerk. APOLOGIES:- Cllr G. Jones. The minutes of the meeting held at Abergorlech Church Hall on the 5th July 2018, were proposed as correct by Cllr. R. Sisto and seconded by Cllr. E. Jones, and duly signed by the chairperson. DECLARATION OF INTEREST – Declaration of interest was made by County Cllr. Mansel Charles, on any planning matters that may arise in this meeting. 9/18/814 MATTERS ARISING a. 6/15/606/1 Road surface between Bronant and Capel Mair, Nantyffin – Needs a new surface. Rolling program and to be surfaced on priority base as per all other sections. Ongoing.7/18 b. 4/16/660/15 Road leading from Nantyffin up to Banc farm, Abergorlech needs major repair work – This work should be undertaken end of this Summer /early Autumn, once the landowner has resolved the discharge of surface water from carriageway. Ongoing. 7/18 c. 6/16/675 Blind dip signage near Pistyllgwyn – John McEvoy has agreed to put road signage on the road ARAF/SLOW on the Brechfa side. It has not materialised. John McEvoy has since arranged a visibility study at this location. d. 6/16/675/2 Defibrillator for Gwernogle and Abergorlech. The community council have one defibrillator and are trying to obtain another one, so that they can be fitted together. -

Carmarthenshire Revised Local Development Plan (LDP) Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Scoping Report

Carmarthenshire Revised Local Development Plan (LDP) Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Scoping Report Appendix B: Baseline Information Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 1. Sustainable Development 1.1 The Carmarthenshire Well-being Assessment (March 2017) looked at the economic, social, environmental and cultural wellbeing in Carmarthenshire through different life stages and provides a summary of the key findings. The findings of this assessment form the basis of the objectives and actions identified in the Draft Well-being Plan for Carmarthenshire. The Assessment can be viewed via the following link: www.thecarmarthenshirewewant.wales 1.2 The Draft Carmarthenshire Well-being Plan represents an expression of the Public Service Board’s local objective for improving the economic, social, environmental and cultural well- being of the County and the steps it proposes to take to meet them. Although the first Well- being Plan is in draft and covers the period 2018-2023, the objectives and actions identified look at delivery on a longer term basis of up to 20-years. 1.3 The Draft Carmarthenshire Well-being Plan will focus on the delivery of four objectives: Healthy Habits People have a good quality of life, and make healthy choices about their lives and environment. Early Intervention To make sure that people have the right help at the right time; as and when they need it. Strong Connections Strongly connected people, places and organisations that are able to adapt to change. Prosperous People and Places To maximise opportunities for people and places in both urban and rural parts of our county. SA – SEA Scoping Report – Appendix B July 2018 P a g e | 2 Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 2. -

Your Local Community Magazine

The Post Over 4600 copies Also ONLINE at Your Local Community Magazine www.postdatum.co.uk Number 275 December 2018 / January 2019 Published by PostDatum, 24 Stone Street, Llandovery, Carms SA20 0JP Tel: 01550 721225 CLWB ROTARI LLANYMDDYFRI ROTARY CLUB OF LLANDOVERY SANTA CLAUS IS COMING TO TOWN (AND THE VILLAGES)! Yes folks it’s that time again, when the aging Rotary support this initiative, then an envelope will be popped Club members (bless them!) don their sparkly hats and through your letter box offering an opportunity to drop shake their collecting pots. We will try to encourage you off your donation locally. wonderful people to give as much as you can spare. Safe in Fri 30th Nov .............................Switch on town lights. the knowledge that every penny collected, will be given out Fri 7th Dec ................................Llandovery West locally to all the good causes and requests that we support. Mon 10th Dec ...........................Llangadog We are delighted to be joined again this year by Tue 11th Dec .............................Cynghordy/Siloh Llandovery Town Crier Joe Beard, who has agreed to Wed 12th Dec ...........................Cilycwm/Rhandirmwyn lead the Sleigh around the town and villages. “Thank Thur 13th Dec ...........................Llanwrda/Llansadwrn you, Joe,”. Fri 14th Dec ..............................Llandovery East Our aim is to visit all areas listed below before 20:30 Mon 17th Dec ...........................Myddfai & Farms hrs (unless otherwise stated), so as not to keep your little Sat 22nd Dec .............................Llandovery Co-op ones up too late. Every year we are blown away by your kindness and Finally, on behalf of President Gary Strevens and all giving nature, as we seem to increase the amount that we club members, may we wish each and every one of you collect year on year. -

Carmarthenshire: the Cycling Hub of Wales Executive Summary January 2018 Carmarthenshire: the Cycling Hub of Wales | Executive Summary JANUARY 2018

CWM RHAEADR CRYCHAN FOREST LLANDOVERY Carmarthen to Merlin Druid Newcastle Emlyn Route BRECHFA NCN 47 Carmarthen to Brechfa Merlin Wizard CARMARTHEN Route ST. CLEARS LLANDYBIE CROSS HANDS AMMANFORD KEY: NCN ROUTE 4 NCN 4 NCN ROUTE 47 ACTIVE TRAVEL TOWNS KIDWELLY MOUNTAIN BIKE NCN 47 BASE WALES COASTAL LLANELLI PATH BURY PORT NCN 4 VELODROME LLANGENNECH & HENDY Carmarthenshire: The Cycling Hub of Wales Executive Summary January 2018 Carmarthenshire: The Cycling Hub of Wales | Executive Summary JANUARY 2018 Background This Cycling Strategy presents a vision designed to make Carmarthenshire ‘The Cycling Hub of Carmarthenshire already has a well-established cycling product. The development of the Wales’. exciting Twyi Valley Cycle Path, the Millennium Coastal Path and the Amman Valley Cycle Path all combine to offer excellent off road cycling opportunities. When opened, the refurbished The aims and objectives of the Strategy have been developed following extensive consultation Velodrome will be one of only two in Wales. While in 2018, Carmarthenshire will host a Stage with a wide range of Stakeholders. of Tour of Britain. This Strategy strikes a balance between developing and promoting cycling for everyday local This Strategy plays a key role in supporting the delivery of not only Active Travel but of all journeys and delivering infrastructure and events capable of attracting the world’s top cyclists aspects of cycling across the County. The Strategy is developed around the following 5 key to Carmarthen. themes, each of which are designed and tailored to maximise cycling opportunities and to The Active Travel (Wales) Act 2013 provides the foundation upon which this Strategy is boost participation across all ages and all levels of ability. -

Tir-Y-Dail Motte, Ammanford Archaeological Evaluation

TIR-Y-DAIL MOTTE, AMMANFORD ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION July 2010 Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For CADW DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO. 2010/48 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO. 100040 Ionawr 2011 January 2011 TIR-Y-DAIL MOTTE, AMMANFORD ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION Gan / By Philip Poucher Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Gwefan: www.archaeolegdyfed.org.uk Website: www. dyfedarchaeology .org.uk Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (50461 6) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. 1198990) and a Registered Charity (No. 504616) CADEIRYDD CHAIRMAN: C R -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Bank House Llangadog Carmarthenshire SA19 9BR Price £69,000

Bank House Llangadog Carmarthenshire SA19 9BR Price £69,000 • Mid Terraced 1/2 Bedroom Village Cottage • In Need Of Total Renovation • Kitchen/Diner, Studio, Bathroom & Workshop • Deceptively Spacious • Convenient Village Location • Rear Garden • Parking To Front General Description EPC Rating: F30 Bank House is a mid terraced 1/2 bedroom property in need of total renovation. The property comprises; 1 bedroom, kitchen/diner, studio/bedroom, bathroom and workshop with all needing works of upgrading. Tel: 01550 720 440 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ctf-uk.com Bank House, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire SA19 9BR Property Description Bathroom Bank House is a mid terraced 1/2 bedroom property in With low level wc, wash hand basin, bath and shower need of total renovation. The property comprises; 1 attachment. Part tiled walls. bedroom, kitchen/diner, studio/bedroom, bathroom and workshop with all needing works of upgrading. Standing Former Workshop (19' 10" x 5' 10") or (6.05m x 1.78m) towards the centre of Llangadog Village in a very With door to rear garden. convenient position for the village amenities which Landing Area include mini market, butchers, post office/general store, doctors surgery, junior school, several public houses and Bedroom/Studio (13' 06" x 13' 05") or (4.11m x 4.09m) places of worship together with a station on the Heart of (these are the average dimensions of irregular shaped Wales line from Shrewsbury to Swansea. room). With exposed beams and roof light. Llangadog is a small village set within the superb Bedroom (14' 07" x 8' 04") or (4.45m x 2.54m) countryside of the Upper Towy valley with the Brecon Above the bedroom is a loft storage area.