Customized Marriage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

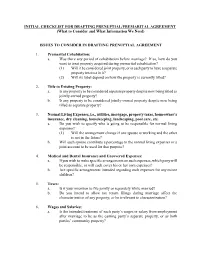

INITIAL CHECKLIST for DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL/PREMARITAL AGREEMENT (What to Consider and What Information We Need)

INITIAL CHECKLIST FOR DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL/PREMARITAL AGREEMENT (What to Consider and What Information We Need) ISSUES TO CONSIDER IN DRAFTING PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENT 1. Premarital Cohabitation: a. Was there any period of cohabitation before marriage? If so, how do you want to treat property acquired during premarital cohabitation? (1) Will it be considered joint property, or is each party to have a separate property interest in it? (2) Will its label depend on how the property is currently titled? 2. Title to Existing Property: a. Is any property to be considered separate property despite now being titled as jointly-owned property? b. Is any property to be considered jointly-owned property despite now being titled as separate property? 3. Normal Living Expenses, i.e., utilities, mortgage, property taxes, homeowner’s insurance, dry cleaning, housekeeping, landscaping, pool care, etc. a. Do you wish to specify who is going to be responsible for normal living expenses? (1) Will the arrangement change if one spouse is working and the other is not in the future? b. Will each spouse contribute a percentage to the normal living expenses or a joint account to be used for that purpose? 4. Medical and Dental Insurance and Uncovered Expenses: a. If you wish to make specific arrangements on such expenses, which party will be responsible, or will each cover his or her own expenses? b. Are specific arrangements intended regarding such expenses for any minor children? 5. Taxes: a. Is it your intention to file jointly or separately while married? b. Do you intend to allow tax return filings during marriage affect the characterization of any property, or be irrelevant to characterization? 6. -

A Note on the Incest Taboo: the Case of the Matrilineal Khasis

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 5, Ver. I (May 2017) PP 41-46 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org A Note on the Incest Taboo: The Case of the Matrilineal Khasis Davina Diengdoh Ropmay (Research Scholar, Department of Sociology, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India) Abstract : Incest Taboo serves as one important aspect under kinship studies. Understanding the rules prohibiting intimate and sexual relations with certain kin throws light on how other facets of a social organisation operate such as marriage, clan organisation and kinship terminology. The existence of the Incest Taboo among the Khasi, a major matrilineal tribal group of Meghalaya, provides us a picture on how such facets are determined. Therefore, this article attempts to describe the bounds of the incest taboo among the Khasis and the serious implication it has towards the maintenance and perpetuation of the society as a whole Keywords: Incest, Exogamy, Incest Taboo, Marriage, Khasi. I. INTRODUCTION The study of Kinship has been a much researched area in sociological and social anthropological studies. It simply seeks to understand on one hand, in what way a person is related to another, and on the other hand, in what way do these people exhibit behaviour with each other as per their relationship. Radcliffe-Brown rightly puts it “A kinship system thus presents to us a complex set of norms, of usages, of patterns of behaviour between kindred” (Radcliffe-Brown 1950: 10). Behaviour patterns which stem out of the social relations between people, customs, norms and usages are important for the functioning of the social machinery. -

Premarital (Antenuptial) and Postnuptial Agreements in Connecticut a Guide to Resources in the Law Library

Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Libraries Copyright © 2002-2019, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. All rights reserved. 2019 Edition Premarital (Antenuptial) and Postnuptial Agreements in Connecticut A Guide to Resources in the Law Library Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Current Premarital Agreement Law...................................................... 4 Table 1: Connecticut Premarital Agreement Act: House Debate ........................ 14 Section 2: Postnuptial Agreement Law .............................................................. 15 Section 3: Prior Premarital Agreement Law ........................................................ 22 Table 2: Three Prong Test ............................................................................ 25 Section 4: Premarital Agreement Form and Content .......................................... 26 Section 5: Enforcement and Defenses ............................................................... 32 Table 3: Surveys of State Premarital Agreement Laws ..................................... 40 Section 6: Modification or Revocation ............................................................... 41 Section 7: Federal Tax Aspect .......................................................................... 44 Section 8: State Tax Aspect ............................................................................. 47 Appendix: Legislative Histories in the Connecticut Courts ................................... -

By Arlene G. Dubin 08-01-2011 Cohabitation Agreements Create

“Sweetheart Deals in High Demand” By Arlene G. Dubin 08-01-2011 Cohabitation agreements create rights and obligations for unmarried couples. Arlene G. Dubin, a partner at Moses & Singer, writes that many people think of cohabitation agreements as the same as prenuptial agreements, but without the “nup.” But there are important distinctions: living together agreements have no specific statutory requirements and are governed by contract principles; and there are potential tax issues not presented by prenups. Unmarried couples made up 12 percent of U.S. couples in 2010, a 25 percent increase in 10 years, according to a recently released U.S. census report.1 The result has been a corresponding surge in the demand for cohabitation or living together agreements. “Cohabs” are fast becoming as popular as “prenups,” and thus an increasingly important part of family law practice. Cohabitation has increased for many reasons. An oft-cited practical reason is the reduction of household expenses. Cohabitation is widely accepted and promoted via celebrity role models, such as Governor Andrew Cuomo and Sandra Lee, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, and Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell. An astounding 40 percent of U.S. adults say they have lived with a partner without the benefit of marriage.2 Cohabitation is often a stepping stone for parties headed for marriage. Studies have found that more than 70 percent of couples who marry today lived together first.3 And often it is a choice for older couples who do not want to upset their family or friends or lose Social Security or other benefits. -

THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN FAMILY LAW and ELDER LAW by Phoebe P

THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN FAMILY LAW AND ELDER LAW by Phoebe P. Hall Tracy N. Retchin Hall & Hall, PLC 1401 Huguenot Road Midlothian, Virginia 23113 (804)897-1515 February 2011 I. INTRODUCTION Family Law and Elder Law are closely related fields sharing a focus on assisting individuals and their family members with legal issues and planning opportunities that arise at critical times in their lives. The specialized knowledge of an attorney in each of these fields can be beneficial to clients seeking advice and guidance with decision-making or when performing advance planning with regard to future needs, particularly when they involve seniors. II. IMPORTANT MATTERS RELATING TO SEPARATION AND DIVORCE FOR SENIORS For an individual contemplating separation or divorce, making vital decisions and taking important steps with long term consequences, it can be instructive and helpful to obtain the advice and guidance or collaborative assistance of both a family law attorney and an elder law attorney. These efforts can be particularly beneficial with matters such as prenuptial agreements, separation, divorce, separate maintenance, spousal support (alimony), property division, and long term care planning for seniors. III. IMPORTANT MATTERS ARISING WHEN SENIORS ARE IN DETERIORATING CIRCUMSTANCES AND THE SENIOR’S CHILDREN, OR COMMITTEES, ARE HANDLING THE FINANCIAL MATTERS, OR WHEN THE SENIOR HAS A GUARDIAN A common situation that can make planning especially complicated is when one or both parties are frail or even incompetent, when the marriage is of short duration, and/or when children of prior marriages are handling their own parent’s finances, perhaps with a power of attorney. -

Prenuptial Agreement Sample

PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENT THIS AGREEMENT made this ________ day of ________________, 20___, by and between JANE SMITH, residing at ___________________________________________, hereinafter referred to as “Jane” or “the Wife”, and JOHN DOE, residing at _____________________________________________, hereinafter referred to as “John” or “the Husband”. W I T N E S S E T H: A. Jane is presently ___ years of age, and has not previously been married and has no children. John is presently ___ years of age, has been married once previously and was divorced in ________. John has three children from his prior marriage, [identify children by name, date of birth and age]. B. The parties hereto have been residing together for a period of years, and in consideration and recognition of their relationship and their mutual commitment, respect and love for one another, the parties contemplate marriage to one another in the near future, and both desire to fix and determine by antenuptial agreement the rights, claims and possible liabilities that will accrue to them by reason of the marriage. C. The parties are cognizant that John has significant assets as reflected in Schedule “A” annexed hereto. It is the parties’ express intention and desire for this agreement to secure not only the pre-marital and separate property rights of John, but also to preserve, shield and protect the beneficial interest which John’s children have in their father’s estate. Inasmuch as John has been previously divorced, both John and Jane desire to enter into a contractual agreement which is intended to govern their financial affairs and obligations to one another in the event of a dissolution of their marital relationship, said agreement being a deliberate and calculated attempt by John and Jane to avoid a painful and costly litigation process. -

The Constitution and Covenant Marriage Legislation: Rumors of a Constitutional Right to Divorce Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

THE CONSTITUTION AND COVENANT MARRIAGE LEGISLATION: RUMORS OF A CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT TO DIVORCE HAVE BEEN GREATLY EXAGGERATED David M. Wagner* Subject to the inherent ambiguity of legislative motivation, we may safely speculate that when a state enacts a covenant marriage statute, it is seeking to make divorce more rare and to distance the moral culture of that state from the "culture of divorce.", This action is premised on a value judgment that marriage is basically good and divorce is basically bad: a value judgment that is simple, intuitive, popular, and far too "tra- ditional" to escape scathing scrutiny by legal academia. 2 This article is an effort to anticipate constitutional attacks on covenant marriage leg- islation based on modern substantive due process, which focuses on indi- vidual moral autonomy, and which includes a "right to marry" couched in terms so individualistic as to imply a correlative right to divorce.3 For a period of time beginning in the 1940s and culminating in the 1970s, the Supreme Court seemed to be developing a "right to marry" doctrine that, in fact, protected not marriage but divorce, by striking down family-protective state laws that acted as obstacles to divorce. It . Associate Professor of Law, Regent University School of Law; A.B. 1980, M.A. 1984, Yale University; J.D. 1992, George Mason University School of Law. I wish to ac- knowledge the valuable assistance of my research assistant, Keith Howell, Regent Univer- sity School of Law 2000. 1 See, e.g., BARBARA DAFOE WHITEHEAD, THE DIVORCE CULTURE: RETHINKING OUR COMMITMENTS TO MARRIAGE AND FAMILY (1997) (arguing for a return to a pro-marriage culture, though not advocating fundamental change to no-fault divorce statutes). -

Marriage Marriage, and the Process of Planning a Wedding, Can Be a Wonderful Thing

An Overview of Marriage Marriage, and the process of planning a wedding, can be a wonderful thing. While there are many guides available to help you plan a wedding, this is a guide to help you plan some of the legal and financial responsibilities that go along with getting married. We hope this guidebook will provide a valuable first step in finding clarity and relief for your legal concerns. If you have additional questions after reading this document, your ARAG® legal plan can help. If you have ideas on how to improve this document, please share them with us at Service@ ARAGlegal.com. If you’re not an ARAG member, please feel free to review this information and contact us to learn how ARAG can offer you affordable legal resources and support. Sincerely, ARAG Customer Care Team 2 Table of Contents Glossary 4 The Decision to Get Married 6 What You Need to Get Legally Married 8 Prenuptial Agreements 9 Different Forms of Unions 15 Changing Your Name 19 Let Us Help You 20 Preparing to Meet Your Attorney 23 Resources for More Information 25 Checklists 26 ARAGLegalCenter.com • 800-247-4184 3 Glossary Civil Union. A relationship between a couple that is legally recognized by a governmental authority and has many of the rights and responsibilities of marriage. Common Law Marriage. A marriage created when two people live together for a significant period of time (not defined in any state), hold themselves out as a married couple, and intend to be married. Community property. A community property state is one in which all property acquired by a husband and wife during their marriage becomes joint property even if it was acquired in the name of only one partner. -

Family Law Berenson Fam Law 00 Fmt F2.Qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page Ii Berenson Fam Law 00 Fmt F2.Qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page Iii

berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page i Family Law berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page ii berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page iii Family Law Doctrine and Practice Steve Berenson Professor of Law Director of Veterans Legal Assistance Clinic Thomas Jefferson School of Law Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page iv Copyright © 2017 Steve Berenson All Rights Reserved ISBN: 978-1-61163-954-4 E-ISBN: 978-1-61163-998-8 LCCN: 2016952078 Carolina Academic Press, LLC 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page v To Deanna, Michaela, and Kory — for making my family life so wonderful. berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page vi berenson fam law 00 fmt f2.qxp 12/2/16 12:20 PM Page vii Contents Table of Cases xxi Table of Authorities xxv Chapter 1 · Introduction 3 Chapter 2 · Premarital Controversies 7 I. Learning Outcomes 7 II. Breach of Promise to Marry 7 Gilbert v. Barkes 9 Discussion Questions 12 III. Other “Heart Balm” Actions 12 IV. Modified Breach of Promise to Marry Claims 13 Tennessee Code Annotated § 36- 3-401 14 Tennessee Code Annotated § 36- 3-404 14 Discussion Question 14 V. -

Documenting Your Family History

DOCUMENTING YOUR FAMILY HISTORY - PRESENTING THE FORMAL GENEALOGICAL PRESENTATION STANDARD - by Brian W. Hutchison, B.Comm. CMA, FSA Scot* INTRODUCTION o, you have now finally hit the moment when it is time to write something on your family history! All those years, or even decades, of research have led you to this moment in time. SIt may seem like a daunting task however I hope that this short article makes some light as to how easy it really can be to take this extra step. You have spent many thousands of hours researching and documenting your study and it is good, if not imperative, that you now take the time to write it right!! My years of experience, and those of my firm in documenting genealogies for clients, allows me to offer you some brief tips in this matter which I hope will be helpful. However, I have not covered the final phase of these projects, specifically printing/publishing and distribution, as that is an entire article on its own. GETTING STARTED It is extremely important from the beginning of this phase to ask yourself three questions: Why am I doing this? Who is the manuscript written for? How much (approximately) do I want this to cost? The answers to these basic questions will play a major role in shaping the type of history/genealogy that you want to compile, print/publish, what it looks like, how many copies you print, how the manuscript will be eventually bound, and how much it will finally cost. You need to make every effort to ensure that the material is easy to read, brings out the special personalities and characters that we all hold, including pictures of the times and the people, charts and graphs that are relevant, and an historical background on the times & places involved, where possible. -

The Yu of Yi-Mei and Chang-Wan in Kwangtung,S Xin-Hui Xian

Genealogy and History: The Yu of Yi-mei and Chang-wan in Kwangtung,s Xin-hui xian By L . E ve A r m e n t r o u t M a Chinese / Chinese American History Project, El Cerrito CAt USA A number of reasons have been advanced to explain why formal clan and lineage1 organizations first became widespread in China during the Song dynasty. Among these is the suggestion that the “ new ’, men (many of obscure origins), brought into the bureaucracy by the Song emphasis on the しonfucian examination system, desired to strength en the fabric of society. One means they chose was encouraging the revitalization and extension of clan and lineage organizations. They did tms in order to fill the void created by the decline of the aristocratic (“ great”) families (Twitchett 1959: 100-101). If these assumptions are true, one would expect to find a certain amount of the “ ordinary ” in the genealogies kept by these groups. 1 his was, indeed, often the case. A good example is that of the Yu 余 lineage that I will introduce in this essay. These Yus lived in the villages of Yi-mei 乂美 and Chang-wan 長湾 in Kwangtung’s Xin-hui xian 新会縣. As we shall see, they provide an interesting case study of a lineage that had its brief moment of glory, constructed a genealogy that helped to reflect this moment, and then faded into relative obscurity. In light of what we know about the distribution of wealth and power in the southern Chinese countryside, there must have been thousands of lineages similar to this one. -

SNP Identity Searching Across Ethnicities, Kinship, and Admixture

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/574566; this version posted March 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. SNP Identity Searching Across Ethnicities, Kinship, and Admixture Authors: Brian S. Helfer & Darrell O. Ricke ABSTRACT Advances in high throughput sequencing (HTS) enables application of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) panels for identification and mixture analysis. Large reference sets of characterized individuals with documented relationships, ethnicities, and admixture are not yet available for characterizing the impacts of different ethnicities, kinships, and admixture on identification and mixture search results for relatives and unrelated individuals. Models for the expected results are presented with comparison results on two in silico datasets spanning four ethnicities, extended kinship relationships, and also admixture between the four ethnicities. KEYWORDS Forensic science, single nucleotide polymorphism, kinship, admixture, identification bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/574566; this version posted March 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Introduction The United States recently expanded the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) loci from 13 to 20 in 2016. The current FBI National DNA Index System (NDIS) database has near 18 million profiles (1). Shifting from sizing short tandem repeat (STR) alleles to high throughput sequencing (HTS) will enable resolution of different STR alleles with the same lengths. Illumina recently introduced the ForenSeq (2) sequencing panel that includes SNPs in addition to STRs.