1 Address for Correspondence Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consultation Report 793 795 London Road

793-795 London Road - proposed red route restrictions Consultation summary July 2016 Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 1 1 Background ................................................................................................................ 2 2 Scheme description .................................................................................................... 2 3 The consultation ......................................................................................................... 4 4 Overview of consultation responses ............................................................................ 5 5 Responses from statutory bodies and other stakeholders ........................................... 7 6 Conclusion and next steps .......................................................................................... 7 Appendix A – Response to issues raised .............................................................................. 8 Appendix B – Consultation Materials ..................................................................................... 9 Appendix C – List of stakeholders consulted ....................................................................... 13 Executive Summary Between 5 February and 17 March 2017, we consulted on proposed changes to parking restrictions at the area in front of 793-795 London Road, Croydon. The consultation received 11 responses, with 7 responses supporting or partially supporting -

Caroline Russell Murad Qureshi

Environment and Housing Committees Caroline Russell Londonwide Assembly Member Chair of the Environment Committee Murad Qureshi Londonwide Assembly Member Chair of the Housing Committee City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP Secretary of State Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy 1 Victoria St London SW1H 0ET (By email) 16 September 2020 Dear Secretary of State, Re. Green Homes Grant and Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund The London Assembly Environment and Housing Committees welcome Government investment in making homes more energy efficient and were pleased to see the Green Homes Grant and Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund announced in the Chancellor’s Summer Statement. The energy efficiency of homes in London is a significant problem. Many Londoners face considerable issues with damp, condensation and cold, which in turn negatively affects their health and wellbeing. As this is such a critical issue for Londoners, the Committees are writing to you to outline some questions and key points for consideration, as information for households about the funds continue to emerge and you and your teams further develop and roll them out. We support the Government’s ambition to reach net zero emissions, but this must be achieved sooner than 2050. In December 2018, the London Assembly passed a motion to declare a climate emergency, calling on the Mayor to do likewise and on the Government to provide him with the powers and funding needed to make London a carbon neutral city by 2030.1 The Mayor declared a climate emergency shortly afterwards, and in early 2020, set a target 1 https://www.london.gov.uk/press-releases/assembly/call-on-mayor-to-declare-climate-emergency Environment and Housing Committees for London to be net zero-carbon by 2030, alongside his manifesto commitment for London to be zero-carbon by 2050. -

The Lord Hunt of Kings Heath Minister for Sustainable Development And

The Lord Hunt of Kings Heath Minister for Sustainable Development and Energy Innovation and Deputy Leader of the House of Lords Nobel House 9 Millbank c/o 17 Smith Square London SW1P 3JR By registered post 20 April 2009 Dear Lord Hunt Is it still government policy to issue smog alerts for London? I sent you an email on Sunday 5 April but am not sure whether you received it so I am resending it as this letter. I am writing on behalf of the Campaign for Clean Air in London (CCAL) to ask you to confirm please whether it is still the government's policy to issue public warnings of significant smog events (i.e. not just those required to be made by law). Perhaps, if the government does not plan to continue this practice, it might 'direct' the Mayor of London to take over responsibility for issuing these warnings to protect public health in London. Clear lines of responsibility would clearly need to be drawn in the latter case. As far as CCAL is aware, the government did not issue a public smog warning before Bonfire night in 2008 or in the week commencing 30 March 2009 week in respect of one of the first summer smogs of 2009. CCAL's considers the lack of such warnings to be surprising - not least when the former was issued in 2006 and 2007 and the latter in 2006, 2007 and 2008. To give you a measure of the severity of the smog in the week commencing 30 March 2009 in London (which coincided with the G20 meetings in London), I received a CERC airTEXT alert on the evening of Thursday 2 April forecasting 'high air pollution everywhere in City of Westminster' - I do not recollect ever before receiving such a severe warning (even in the high summer). -

Chinese Orient for Labour Sino-British ‘New’ Relations – Gordon Brown’S First Visit to China As PM

The Official Newsletter of the August 2008 • Volume 1 Chinese Orient for Labour Sino-British ‘new’ relations – Gordon Brown’s first visit to China as PM was accompanied on his trip by more than twenty British and European business figures. The two countries were keen to boost bilateral trade by 50% by 2010. This, according to Mr Brown, will create “tens of thousands” of jobs in the UK. Mr Brown was also optimistic that 100 new Chinese companies would invest in the from the Chair… UK by 2010. Mr Brown also officiated at the opening of the Chinese division of the London Stock Exchange in Beijing. 2008 heralds a step change in the On environmental issues, Mr Brown said that Britain and China activities of Chinese for Labour and we will work together on the development of higher level of are extremely happy that Ian McCartney cooperation which will lead the world in the creation of eco-cities has agreed to be one of our Patrons and and eco-towns. our Parliamentary Champion. His Ping Pong diplomacy was brought into play when the Chinese experience of the Party and of Premier Wen Jiabao and Gordon Brown watched a table tennis government will be invaluable as we seek performance by Chinese and British athletes at Renmin to grow our organization and we look University. During this visit, the Chinese Premier extended an forward to working closely with him on the invitation to Mr & Mrs Brown to the Beijing Olympics. Shanghai Expo 2010. The three-day visit also took Mr Brown to Shanghai, a major Our campaigning during the London economic and financial centre in east China, where he met elections and our annual CNY dinner has Prime Minister Gordon Brown and his wife, Sarah, were in Beijing Chinese entrepreneurs and witnessed the signing of a formed the core of our work. -

Branching out the Future for London's Street Trees

EMBARGOED until 00.01am on Tuesday, 19 April 2011 Environment Committee Branching Out The future for London's street trees April 2011 EMBARGOED until 00.01am on Tuesday, 19 April 2011 EMBARGOED until 00.01am on Tuesday, 19 April 2011 Environment Committee Branching Out The future for London's street trees April 2011 Cover image source: George Raszka EMBARGOED until 00.01am on Tuesday, 19 April 2011 Copyright Greater London Authority April 2011 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN This publication is printed on recycled paper EMBARGOED until 00.01am on Tuesday, 19 April 2011 Environment Committee Members Darren Johnson Green (Chair) Murad Qureshi Labour (Deputy Chair) Gareth Bacon Conservative James Cleverly Conservative Roger Evans Conservative Nicky Gavron Labour Mike Tuffrey Liberal Democrat The Environment Committee agreed the following terms of reference for its investigation on 1 December 2010 • To examine what progress has been made for street trees in London since the committee’s 2007 report; and • What the future holds for street trees, and where responsibility for planting and maintenance will lie. The Committee would welcome feedback on this report. For further information contact: Jo Sloman, Assistant Scrutiny Manager, on 020 7983 4942 or [email protected]. For media enquiries please contact: Lisa Moore on 020 7983 4228 or [email protected]; or Julie Wheldon on 020 7983 4228 or [email protected] -

2014 Wwwbbpower-Inspiration.Com TALENT | SUCCESS | LEADERSHIP

TALENT . SUCCESS . LEADERSHIP 2014 wwwbbpower-inspiration.com TALENT | SUCCESS | LEADERSHIP Welcome to the 2014 edition of the British Bangladeshi Power & Inspiration Here you will find 100 bright, ambitious and successful British Bangladeshi names across 19 categories demonstrating the dynamic, entrepreneurial, philanthropic, pioneering and innovative nature of this community. The 20th category of the 2014 list is the “People’s Choice” where for the first time the general public were invited to nominate their most inspirational British Bangladeshi. The judges are delighted to announce the 5 unsung heroes of this category who serve to remind us of the strength and courage of individuals and the potential for the future. We are often asked why we produce this list and the answer lies with the word “inspiration”. The next generation is rising fast and we aim to be at the forefront of this revolution. Recent studies have shown that in GCSE exams taken at the age of 16, Bangladeshi girls now outperform their peers. On its own this is an amazing sound bite of achievement, but imagine what more could be achieved by providing strong, powerful role models and mentors for young girls (and boys!) from across all industries and categories that the BB Power & Inspiration represents. That is why following the success of our recent lawyers networking event, we will be hosting a series of “inspirational events” under the BB Power & Inspiration banner throughout 2014 for sectors such business and enterprise, medicine, public service and the arts. Please keep checking the website for further details. As if that wasn’t enough, it has become tradition that we do a little extra and so this year, please take a look at the 10 inspirational Bangladeshi figures who live away from our shores but who demonstrate our values of talent, success, leadership and are exceptional role models for all. -

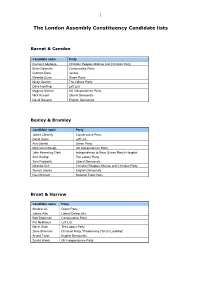

The London Assembly Constituency Candidate Lists

1 The London Assembly Constituency Candidate lists Barnet & Camden Candidate name Party Clement Adebayo Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Brian Coleman Conservative Party Graham Dare Veritas Miranda Dunn Green Party Nicky Gavron The Labour Party Dave Hoefling Left List Magnus Nielsen UK Independence Party Nick Russell Liberal Democrats David Stevens English Democrats Bexley & Bromley Candidate name Party James Cleverly Conservative Party David Davis Left List Ann Garrett Green Party Mick Greenhough UK Independence Party John Hemming-Clark Independence to Save Queen Mary's Hospital Alex Heslop The Labour Party Tom Papworth Liberal Democrats Miranda Suit Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Steven Uncles English Democrats Paul Winnett National Front Party Brent & Harrow Candidate name Party Shahrar Ali Green Party James Allie Liberal Democrats Bob Blackman Conservative Party Pat McManus Left List Navin Shah The Labour Party Zena Sherman Christian Party "Proclaiming Christ's Lordship" Arvind Tailor English Democrats Sunita Webb UK Independence Party 2 The London Assembly Constituency Candidate lists City & East (Newham, Barking & Dagenham, Tower Hamlets, City of London) Candidate name Party Hanif Abdulmuhit Respect (George Galloway) Robert Bailey British National Party John Biggs The Labour Party Candidate Philip Briscoe Conservative Party Thomas Conquest Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Julie Crawford Independent Heather Finlay Green Party Michael Gavan Left List John Griffiths English Democrats Rajonuddin -

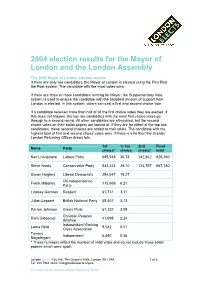

2004 Election Results for the Mayor of London and the London Assembly

2004 election results for the Mayor of London and the London Assembly The 2004 Mayor of London election results If there are only two candidates, the Mayor of London is elected using the First Past the Post system. The candidate with the most votes wins. If there are three or more candidates running for Mayor, the Supplementary Vote system is used to ensure the candidate with the broadest amount of support from London is elected. In this system, voters can cast a first and second choice vote. If a candidate receives more than half of all the first choice votes they are elected. If this does not happen, the top two candidates with the most first choice votes go through to a second round. All other candidates are eliminated, but the second choice votes on their ballot papers are looked at. If they are for either of the top two candidates, these second choices are added to their totals. The candidate with the highest total of first and second choice votes wins. If there is a tie then the Greater London Returning Officer draws lots. 1st % 1st 2nd Final Name Party choice* choice choice* total Ken Livingstone Labour Party 685,548 36.78 142,842 828,390 Steve Norris Conservative Party 542,423 29.10 124,757 667,180 Simon Hughes Liberal Democrats 284,647 15.27 UK Independence Frank Maloney 115,666 6.21 Party Lindsey German Respect 61,731 3.31 Julian Leppert British National Party 58,407 3.13 Darren Johnson Green Party 57,332 3.08 Christian Peoples Ram Gidoomal 41,698 2.24 Alliance Independent Working Lorna Reid 9,542 0.51 Class Association Tammy Independent 6,692 0.36 Nagalingam * These numbers reflect the number of valid votes and do not include those ballot papers which were spoilt. -

London's Political

CONSTITUENCY MP (PARTY) MAJORITY Barking Margaret Hodge (Lab) 15,272 Battersea Jane Ellison (Con) 7,938 LONDON’S Beckenham Bob Stewart (Con) 18,471 Bermondsey & Old Southwark Neil Coyle (Lab) 4,489 Bethnal Green & Bow Rushanara Ali (Lab) 24,317 Bexleyheath & Crayford David Evennett (Con) 9,192 POLITICAL Brent Central Dawn Butler (Lab) 19,649 Brent North Barry Gardiner (Lab) 10,834 Brentford & Isleworth Ruth Cadbury (Lab) 465 Bromley & Chislehurst Bob Neill (Con) 13,564 MAP Camberwell & Peckham Harriet Harman (Lab) 25,824 Carshalton & Wallington Tom Brake (LD) 1,510 Chelsea & Fulham Greg Hands (Con) 16,022 This map shows the political control Chingford & Woodford Green Iain Duncan Smith (Con) 8,386 of the capital’s 73 parliamentary Chipping Barnet Theresa Villiers (Con) 7,656 constituencies following the 2015 Cities of London & Westminster Mark Field (Con) 9,671 General Election. On the other side is Croydon Central Gavin Barwell (Con) 165 Croydon North Steve Reed (Lab [Co-op]) 21,364 a map of the 33 London boroughs and Croydon South Chris Philp (Con) 17,410 details of the Mayor of London and Dagenham & Rainham Jon Cruddas (Lab) 4,980 London Assembly Members. Dulwich & West Norwood Helen Hayes (Lab) 16,122 Ealing Central & Acton Rupa Huq (Lab) 274 Ealing North Stephen Pound (Lab) 12,326 Ealing, Southall Virendra Sharma (Lab) 18,760 East Ham Stephen Timms (Lab) 34,252 Edmonton Kate Osamor (Lab [Co-op]) 15,419 Eltham Clive Efford (Lab) 2,693 Enfield North Joan Ryan (Lab) 1,086 Enfield, Southgate David Burrowes (Con) 4,753 Erith & Thamesmead -

Bbpi2012.Pdf

2012 - BRITISH BANGLADESHI POWER 100 2012 - BRITISH BANGLADESHI POWER 100 Entrepreneur and Business Brand Politics and Policy Education, Culture and Sports Catering Industry Media Women Community and Voluntary Organisations Iqbal Ahmed OBE Rushanara Ali MP Prof Andy Miah (BA, MPhil, Bazlur Rashid MBE Ahmed us Samad Irene Zubaida Khan Bangladesh Caters Chairman and Chief Executive of the MP for Bethnal Green and Bow PhD, FRSA) Restaurateur and other business Chowdhury JP (FISMM, Human Rights Activist Irene is Association FCMI, FIH) Seamark PLC This Manchester based Rushanara is the first British Professor in Ethics & Emerging entities both in the UK and Chancellor of the University of (BCA) Umbrella organization of businessman built his fortunes on Bangladeshi to be elected to Technologies and Director of the Creative Bangladesh Bazlur is President of the Chairman of Channel S, founder of the Salford and in 2001 she was the first approximately 12,000 British seafood companies, the group has parliament, having defeated George Futures Research Centre at the University Bangladesh Caterers Association. His Potrika Newsweekly, businessman and woman, the first Asian, and the first Bangladeshi restaurants across the branches all over the world. One of Galloway in the 2010 General of the West of Scotland Andy is a fresh inspirational leadership has community activist Under Ahmed’s Muslim to guide the world’s largest UK. The BCA has been representing the richest men in the UK, he is the Election. She was immediately thinking academic, who is a regular transformed the organisation and he guidance Channel S is now one of the human rights organization, Amnesty the Bangladeshi curry industry for 51 highest ranked British Bangladeshi appointed to the Labour front bench writer for newspapers around the world was awarded with an MBE in the most watched ethnic channels in International as its seventh Secretary years. -

Standing up for London

Standing up for London London Assembly’s Annual Report 2011-12 Contents Welcome Brian Coleman Assembly Members what they do? Dee Doocey Holding the Mayor to account Len Duvall Safety and Policing Roger Evans Housing and Planning Nicky Gavron Transport Darren Johnson Health and Community Jenny Jones London’s Economy Joanne McCartney Environment and Climate Change Kit Malthouse The 2012 Games Steve O’Connell How the Assembly uses your money Caroline Pidgeon Murad Qureshi 2008-12 London Assembly Members Navin Shah Tony Arbour JP Valerie Shawcross Jennette Arnold Richard Tracey JP Gareth Bacon Mike Tuffrey Richard Barnbrook Richard Barnes London Assembly - Membership of Committee 2010-11 John Biggs 2008 Election Results Constituency Assembly Members Andrew Boff Londonwide Members Victoria Borwick Turnout and technical information James Cleverly Published reports 2011-12 2|3 London Assembly’s Annual Report 2011-12 Welcome Welcome to the latest London Assembly the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime Our role Londoners can see and hear what is being annual report, which sets out the work we (MOPC) which, along with the London The London Assembly is a watchdog for done on their behalf. The Assembly has have done over the year to April 2012. The Assembly Police and Crime Committee, London. It holds Mayor Boris Johnson and an active programme of engagement with Assembly is required by law to produce this replaced the Metropolitan Police Authority his advisers to account by publicly examining schools, colleges and universities encouraging report but, more importantly, it is a chance (MPA) in January 2012. policies, activities and decisions in key students to come to City Hall to learn about for us to tell Londoners what we have been The remaining sections reflect the priorities areas like policing; housing and planning; their city government and watch it in action doing on your behalf. -

In This Issue INTRODUCTION LTN TRIAL SCHEME TIME for CHANGE 6 14 from the CHAIRMAN 2 from the EDITOR 4

SEBRA NEWS W2 In this Issue INTRODUCTION LTN TRIAL SCHEME TIME FOR CHANGE 6 14 FROM THE CHAIRMAN 2 FROM THE EDITOR 4 SPECIAL ISSUE No 100 AUTUMN 2020 SAFETY VALVE QUEENSWAY PARADE QUESTIONS 16 SUPPORTING CYCLE LANES 17 SAVE OUR TWO PLANE TREES 18 LONDON PROPERTY DISGRACE 22 AROUND BAYSWATER MY TWO UNSUNG HEROES 43 SEBRA'S FIRST PRESS COVERAGE 50 BOB ROGERS' CORNER 62 MORE ABOUT W H SMITH 66 WCC LEADER'S SEBRA'S 50th HEATHROW WAKE UP CALL 67 26 LATEST UPDATE 29 ANNIVERSARY SEBRA - RESPECTING THE PAST 70 PHOTOS OF PEOPLE AND PARKS 74 A BAYSWATER MISCELLANY 82 COMMENTS ON OUR STREETS 84 FORTY YEARS OF DEVOTION 85 BAYSWATER'S LOST FOUNTAINS 88 BEAUTIFUL PLACES AND THINGS 90 HALLFIELD SCHOOL NEWS 102 POLICING BAYSWATER 104 CELEBRATING 100 MAGAZINES 107 SHOPPING AND RESTAURANTS 114 HEALTH AND WELLBEING SMOKE AND MIRRORS 118 HALLFIELD ESTATE RUBY - A FOUR OSTEOARTHRITIS MYTHS 120 44 THE FIRST 73 YEARS 49 LEGGED FRIEND TIPS TO BEAT THE BLOAT 121 THE ALEXANDER TECHNIQUE 122 PORCHESTER CENTRE NEWS 123 THE ROYAL PARKS THE PARKS WELCOME YOU 126 CRYSTAL PALACE VIRTUAL TOUR 127 NEWS FROM THE FRIENDS 128 SERPENTINE GALLERIES 132 POLITICAL COMMENTARY KAREN BUCK MP 134 NICKIE AIKEN MP 136 KEEPING TO THE RIGHT 138 NEW ELIZABETH THE COW KEEPING TO THE LEFT 140 57 LINE STATION 60 A REMARKABLE PUB CITY HALL NEWS WARD BUDGETS UPDATE 142 YOUR COUNCILLORS WRITE 143 PROUD TO BE SERVING OUR PROPERTY AND LICENSING MEMBERS AND THE COMMUNITY CHESTERTONS MARKET NEWS 150 KNIGHT FRANK INSIGHT 152 LICENSING SEBRALAND 154 th LETTERS AND ABOUT SEBRA SEBRA’S 50 ANNIVERSARY AND YOUR LETTERS 156 ABOUT SEBRA 159 100 EDITIONS OF OUR MAGAZINE SEBRA NEWS W2 - AUTUMN 2020 1 INTRODUCTION From the Chairman Chairman: John Zamit London.