Branching out the Future for London's Street Trees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consultation Report 793 795 London Road

793-795 London Road - proposed red route restrictions Consultation summary July 2016 Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 1 1 Background ................................................................................................................ 2 2 Scheme description .................................................................................................... 2 3 The consultation ......................................................................................................... 4 4 Overview of consultation responses ............................................................................ 5 5 Responses from statutory bodies and other stakeholders ........................................... 7 6 Conclusion and next steps .......................................................................................... 7 Appendix A – Response to issues raised .............................................................................. 8 Appendix B – Consultation Materials ..................................................................................... 9 Appendix C – List of stakeholders consulted ....................................................................... 13 Executive Summary Between 5 February and 17 March 2017, we consulted on proposed changes to parking restrictions at the area in front of 793-795 London Road, Croydon. The consultation received 11 responses, with 7 responses supporting or partially supporting -

Caroline Russell Murad Qureshi

Environment and Housing Committees Caroline Russell Londonwide Assembly Member Chair of the Environment Committee Murad Qureshi Londonwide Assembly Member Chair of the Housing Committee City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP Secretary of State Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy 1 Victoria St London SW1H 0ET (By email) 16 September 2020 Dear Secretary of State, Re. Green Homes Grant and Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund The London Assembly Environment and Housing Committees welcome Government investment in making homes more energy efficient and were pleased to see the Green Homes Grant and Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund announced in the Chancellor’s Summer Statement. The energy efficiency of homes in London is a significant problem. Many Londoners face considerable issues with damp, condensation and cold, which in turn negatively affects their health and wellbeing. As this is such a critical issue for Londoners, the Committees are writing to you to outline some questions and key points for consideration, as information for households about the funds continue to emerge and you and your teams further develop and roll them out. We support the Government’s ambition to reach net zero emissions, but this must be achieved sooner than 2050. In December 2018, the London Assembly passed a motion to declare a climate emergency, calling on the Mayor to do likewise and on the Government to provide him with the powers and funding needed to make London a carbon neutral city by 2030.1 The Mayor declared a climate emergency shortly afterwards, and in early 2020, set a target 1 https://www.london.gov.uk/press-releases/assembly/call-on-mayor-to-declare-climate-emergency Environment and Housing Committees for London to be net zero-carbon by 2030, alongside his manifesto commitment for London to be zero-carbon by 2050. -

The Lord Hunt of Kings Heath Minister for Sustainable Development And

The Lord Hunt of Kings Heath Minister for Sustainable Development and Energy Innovation and Deputy Leader of the House of Lords Nobel House 9 Millbank c/o 17 Smith Square London SW1P 3JR By registered post 20 April 2009 Dear Lord Hunt Is it still government policy to issue smog alerts for London? I sent you an email on Sunday 5 April but am not sure whether you received it so I am resending it as this letter. I am writing on behalf of the Campaign for Clean Air in London (CCAL) to ask you to confirm please whether it is still the government's policy to issue public warnings of significant smog events (i.e. not just those required to be made by law). Perhaps, if the government does not plan to continue this practice, it might 'direct' the Mayor of London to take over responsibility for issuing these warnings to protect public health in London. Clear lines of responsibility would clearly need to be drawn in the latter case. As far as CCAL is aware, the government did not issue a public smog warning before Bonfire night in 2008 or in the week commencing 30 March 2009 week in respect of one of the first summer smogs of 2009. CCAL's considers the lack of such warnings to be surprising - not least when the former was issued in 2006 and 2007 and the latter in 2006, 2007 and 2008. To give you a measure of the severity of the smog in the week commencing 30 March 2009 in London (which coincided with the G20 meetings in London), I received a CERC airTEXT alert on the evening of Thursday 2 April forecasting 'high air pollution everywhere in City of Westminster' - I do not recollect ever before receiving such a severe warning (even in the high summer). -

1 Address for Correspondence Mr

www.diabetologists-abcd.org.uk Address for correspondence ABCD Secretariat Red Hot Irons Ltd P O Box 2927 Malmesbury SN16 0WZ Tel: 01666 840589 Mr Murad Qureshi City Hall The Queen’s walk More London London SW1E 2AA Friday, May 31 2013 RE: Proposed London Assembly review of diabetes care in London (Ref HEC/CM) Dear Mr Qureshi, Thank you for asking for the views of the ABCD diabetes specialist group on key areas for diabetes care in London. These are addressed individually below: Why is London experiencing such a high growth in Type 2 Diabetes and what impact is this growth having on health spend? Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM) has greater prevalence in people and communities of Afro- Caribbean, Asian, Chinese and Arabic origin and prevalence figures in a cosmopolitan city such as London reflect this variation. Other risk factors which are not specific to London, but contribute to the increased risk of developing T2DM, are principally obesity, which is due to dietary factors and sedentary lifestyles. A background ageing population produces further increased prevalence as the risk of developing T2DM rises with age. Eight per cent of the UK diabetes healthcare budget is still spent on the care and treatment of diabetes-related complications and this represents 10% of the annual NHS budget in England.1 Early diagnosis and improved quality of care for people with T2DM is crucial to prevent further projected rises in healthcare spend on this condition and related complications. 1 How might further growth in type 2 diabetes be curbed? Prevention and effective management of obesity should, in part, mitigate the alarming rise in the incidence of T2DM. -

Chinese Orient for Labour Sino-British ‘New’ Relations – Gordon Brown’S First Visit to China As PM

The Official Newsletter of the August 2008 • Volume 1 Chinese Orient for Labour Sino-British ‘new’ relations – Gordon Brown’s first visit to China as PM was accompanied on his trip by more than twenty British and European business figures. The two countries were keen to boost bilateral trade by 50% by 2010. This, according to Mr Brown, will create “tens of thousands” of jobs in the UK. Mr Brown was also optimistic that 100 new Chinese companies would invest in the from the Chair… UK by 2010. Mr Brown also officiated at the opening of the Chinese division of the London Stock Exchange in Beijing. 2008 heralds a step change in the On environmental issues, Mr Brown said that Britain and China activities of Chinese for Labour and we will work together on the development of higher level of are extremely happy that Ian McCartney cooperation which will lead the world in the creation of eco-cities has agreed to be one of our Patrons and and eco-towns. our Parliamentary Champion. His Ping Pong diplomacy was brought into play when the Chinese experience of the Party and of Premier Wen Jiabao and Gordon Brown watched a table tennis government will be invaluable as we seek performance by Chinese and British athletes at Renmin to grow our organization and we look University. During this visit, the Chinese Premier extended an forward to working closely with him on the invitation to Mr & Mrs Brown to the Beijing Olympics. Shanghai Expo 2010. The three-day visit also took Mr Brown to Shanghai, a major Our campaigning during the London economic and financial centre in east China, where he met elections and our annual CNY dinner has Prime Minister Gordon Brown and his wife, Sarah, were in Beijing Chinese entrepreneurs and witnessed the signing of a formed the core of our work. -

2014 Wwwbbpower-Inspiration.Com TALENT | SUCCESS | LEADERSHIP

TALENT . SUCCESS . LEADERSHIP 2014 wwwbbpower-inspiration.com TALENT | SUCCESS | LEADERSHIP Welcome to the 2014 edition of the British Bangladeshi Power & Inspiration Here you will find 100 bright, ambitious and successful British Bangladeshi names across 19 categories demonstrating the dynamic, entrepreneurial, philanthropic, pioneering and innovative nature of this community. The 20th category of the 2014 list is the “People’s Choice” where for the first time the general public were invited to nominate their most inspirational British Bangladeshi. The judges are delighted to announce the 5 unsung heroes of this category who serve to remind us of the strength and courage of individuals and the potential for the future. We are often asked why we produce this list and the answer lies with the word “inspiration”. The next generation is rising fast and we aim to be at the forefront of this revolution. Recent studies have shown that in GCSE exams taken at the age of 16, Bangladeshi girls now outperform their peers. On its own this is an amazing sound bite of achievement, but imagine what more could be achieved by providing strong, powerful role models and mentors for young girls (and boys!) from across all industries and categories that the BB Power & Inspiration represents. That is why following the success of our recent lawyers networking event, we will be hosting a series of “inspirational events” under the BB Power & Inspiration banner throughout 2014 for sectors such business and enterprise, medicine, public service and the arts. Please keep checking the website for further details. As if that wasn’t enough, it has become tradition that we do a little extra and so this year, please take a look at the 10 inspirational Bangladeshi figures who live away from our shores but who demonstrate our values of talent, success, leadership and are exceptional role models for all. -

A Mayor and Assembly for London. Report

A Mayor and Assembly for London: 10 years on Report of Conference at LSE 2 nd July 2010 Opening remarks of Chairman, Emeritus Professor George Jones, Chairman of the Greater London Group [GLG] This conference follows one of May 2007 held at City Hall, which had looked at the performance and demise of the Greater London Council [GLC]. Notable speakers at that event were the then Mayor, Ken Livingstone, and Lord (Desmond) Plummer, a former Conservative Leader of the GLC, who had since died. That earlier event was timed to mark the 40-year anniversary of the date when Plummer had become leader. Earlier this year L.J. [Jim] Sharpe died. He had been a research officer with the GLG in the early 1960s and had helped prepare evidence leading to the establishment of the GLC. He went on to write two pioneering GLG papers about the 1961 London County Council (LCC) Elections called A Metropolis Votes (1962) and about Research in Local Government (1965) . He remained a frequent visitor to the Group and writer about London government. I would like to dedicate this conference to Jim’s memory. The Group also lost a few days ago William Plowden who sat with me at GLG Monday afternoon meetings under the chairmanship of William Robson when I first joined the Group in 1966. Today’s conference is timely since the vesting day of the Greater London Authority [GLA], when it came into being, is ten years ago tomorrow. The objective of the conference is to assess the performance of the Mayor and Assembly that make up the GLA, looking at why and how it came into being, its achievements and disappointments. -

517 / 2004-Maylands Field

GREATER LONDON AUTHORITY London Assembly 31 March 2004 Report No: 5 Subject: Questions to the Mayor Report of: Director Of Secretariat 342 / 2004 - Pedicabs Jenny Jones Can you provide us with a timetable for TfL reporting on the registration of Pedicabs, and moving towards their proper regulation? . 343 / 2004 - London-wide basis of Olympic Games bid Andrew Pelling While there is very good merit in our Olympic bid owing to the prospective concentration of facilities for athletes at our East London base, I am sure that you would agree with me that a successful Olympic bid will also be secured by emphasising the London-wide nature of the Olympic Games bid. What comments would you like to make about the London-wide basis of our bid? . 344 / 2004 - Traffic Signals in Croydon Andrew Pelling As part of the TfL work at the junction of Addington Road and Farleigh Road in Croydon, the decision has been made to remove the traffic lights which used to advise motorists whether or not traffic had been signalled to continue into their path and which were located ahead of motorists turning right at that junction. Please can we have these traffic lights reinstated? 345 / 2004 - Brighton Road, Coulsdon Andrew Pelling Why is it necessary to continue to designate the Brighton Road in the centre of Coulsdon as a Red Route after the construction of the Coulsdon Inner Relief Road? . 1 346 / 2004 - Traffic movements in Upper Norwood Andrew Pelling The unpopular one-way system introduced in Upper Norwood looks like being made permanent by the London Borough of Croydon. -

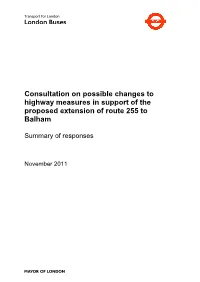

255 Consultation Report

Consultation on possible changes to highway measures in support of the proposed extension of route 255 to Balham Summary of responses November 2011 Contents Section Page 1 Introduction 3 2 The consultation 3 3 Responses from members of the public 5 4 Responses from statutory bodies and other 8 stakeholders Appendices A Copy of the consultation letter 9 B Consultation area 14 C List of stakeholders consulted 16 2 1. Introduction In summer 2009 TfL consulted stakeholders and the local community about plans to extend bus route 255 from Streatham Hill to Balham. The route included Weir Road and Old Devonshire Road. The 2009 consultation response was mainly positive, particularly regarding the benefits of a new bus service in the parts of the area furthest from existing routes. There were 689 responses from members of the public of which 472 were generally supportive, 188 generally opposed and 29 neutral. Many of the local people who came to the consultation exhibitions in Weir Road community centre said they would find it easier to use the bus than take a long walk to and from their home, especially where they were older and/or do not have a car. However some concerns were raised about traffic issues, noise, changes to parking and changes to highway infrastructure, particularly on Old Devonshire Road in the London Borough of Wandsworth. TfL would still like to introduce the extended bus service to improve public transport facilities in the area and meet local requests. The concerns raised in the consultation have been discussed with both Lambeth and Wandsworth Councils. -

Roger Evans (Chairman)

Appendix 2 London Assembly (Plenary) – 5 March 2008 Transcript of Question and Answer Session with Simon Fletcher (Chief of Staff, GLA) and John Ross (Director, Economic and Business Policy, GLA) Sally Hamwee (Chair): We now move to the main item on today’s agenda: the question and answer session regarding the funding of organisations and GLA Group corporate governance, the Corporate Governance Review. Can I start by asking Simon Fletcher, as Chief of the Mayor’s Staff, to what extent you are responsible in your role as Chief of Staff for regulating and supervising the conduct of the Mayoral Advisers? Simon Fletcher (Chief of Staff, GLA): I would say my responsibility is to ensure that the Mayor’s advisers and directors are providing the Mayor with the best possible advice and do so in a timely fashion. That is a role of regulation, if you want to call it that, because it involves making sure that the most important issues facing the city are properly discussed and that the appropriate action is taken to deliver the Mayor’s priorities. The Mayor’s directors are people who directly report to me. Sally Hamwee (Chair): The question was about conduct but Mike Tuffrey has already caught my eye, so he might pursue that. Mike Tuffrey (AM): Simon, last time you were before us, a couple of years ago now, you painted a picture- Simon Fletcher (Chief of Staff, GLA): A bit more recently than that. Mike Tuffrey (AM): No, sorry, I mean in terms of answering questions regarding how the Mayor’s Office functions. -

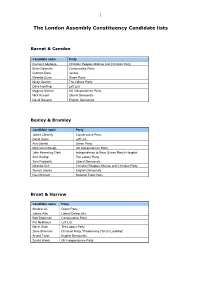

The London Assembly Constituency Candidate Lists

1 The London Assembly Constituency Candidate lists Barnet & Camden Candidate name Party Clement Adebayo Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Brian Coleman Conservative Party Graham Dare Veritas Miranda Dunn Green Party Nicky Gavron The Labour Party Dave Hoefling Left List Magnus Nielsen UK Independence Party Nick Russell Liberal Democrats David Stevens English Democrats Bexley & Bromley Candidate name Party James Cleverly Conservative Party David Davis Left List Ann Garrett Green Party Mick Greenhough UK Independence Party John Hemming-Clark Independence to Save Queen Mary's Hospital Alex Heslop The Labour Party Tom Papworth Liberal Democrats Miranda Suit Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Steven Uncles English Democrats Paul Winnett National Front Party Brent & Harrow Candidate name Party Shahrar Ali Green Party James Allie Liberal Democrats Bob Blackman Conservative Party Pat McManus Left List Navin Shah The Labour Party Zena Sherman Christian Party "Proclaiming Christ's Lordship" Arvind Tailor English Democrats Sunita Webb UK Independence Party 2 The London Assembly Constituency Candidate lists City & East (Newham, Barking & Dagenham, Tower Hamlets, City of London) Candidate name Party Hanif Abdulmuhit Respect (George Galloway) Robert Bailey British National Party John Biggs The Labour Party Candidate Philip Briscoe Conservative Party Thomas Conquest Christian Peoples Alliance and Christian Party Julie Crawford Independent Heather Finlay Green Party Michael Gavan Left List John Griffiths English Democrats Rajonuddin -

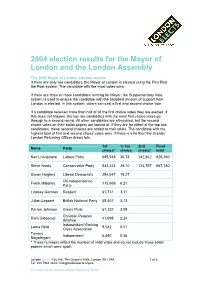

2004 Election Results for the Mayor of London and the London Assembly

2004 election results for the Mayor of London and the London Assembly The 2004 Mayor of London election results If there are only two candidates, the Mayor of London is elected using the First Past the Post system. The candidate with the most votes wins. If there are three or more candidates running for Mayor, the Supplementary Vote system is used to ensure the candidate with the broadest amount of support from London is elected. In this system, voters can cast a first and second choice vote. If a candidate receives more than half of all the first choice votes they are elected. If this does not happen, the top two candidates with the most first choice votes go through to a second round. All other candidates are eliminated, but the second choice votes on their ballot papers are looked at. If they are for either of the top two candidates, these second choices are added to their totals. The candidate with the highest total of first and second choice votes wins. If there is a tie then the Greater London Returning Officer draws lots. 1st % 1st 2nd Final Name Party choice* choice choice* total Ken Livingstone Labour Party 685,548 36.78 142,842 828,390 Steve Norris Conservative Party 542,423 29.10 124,757 667,180 Simon Hughes Liberal Democrats 284,647 15.27 UK Independence Frank Maloney 115,666 6.21 Party Lindsey German Respect 61,731 3.31 Julian Leppert British National Party 58,407 3.13 Darren Johnson Green Party 57,332 3.08 Christian Peoples Ram Gidoomal 41,698 2.24 Alliance Independent Working Lorna Reid 9,542 0.51 Class Association Tammy Independent 6,692 0.36 Nagalingam * These numbers reflect the number of valid votes and do not include those ballot papers which were spoilt.