Air Power in Afghanistan How NATO Changed the Rules, 2008-2014 Report by Robert Perkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University

INCENDIARY WARS: The Transformation of United States Air Force Bombing Policy in the WWII Pacific Theater Gilad Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University Faculty Advisor: Professor Mark Mazower Second Reader: Professor Alan Brinkley INCENDIARY WARS 1 Note to the Reader: For the purposes of this essay, I have tried to adhere to a few conventions to make the reading easier. When referring specifically to a country’s aerial military organization, I capitalize the name Air Force. Otherwise, when simply discussing the concept in the abstract, I write it as the lower case air force. In accordance with military standards, I also capitalize the entire name of all code names for operations (OPERATION MATTERHORN or MATTERHORN). Air Force’s names are written out (Twentieth Air Force), the bomber commands are written in Roman numerals (XX Bomber Command, or simply XX), while combat groups are given Arabic numerals (305th Bomber Group). As the story shifts to the Mariana Islands, Twentieth Air Force and XXI Bomber Command are used interchangeably. Throughout, the acronyms USAAF and AAF are used to refer to the United States Army Air Force, while the abbreviation of Air Force as “AF” is used only in relation to a numbered Air Force (e.g. Eighth AF). Table of Contents: Introduction 3 Part I: The (Practical) Prophets 15 Part II: Early Operations Against Japan 43 Part III: The Road to MEETINGHOUSE 70 Appendix 107 Bibliography 108 INCENDIARY WARS 2 Introduction Curtis LeMay sat awake with his trademark cigar hanging loosely from his pursed ever-scowling lips (a symptom of his Bell’s Palsy, not his demeanor), with two things on his mind. -

Explosive Weapon Effectsweapon Overview Effects

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS EXPLOSIVEEXPLOSIVE WEAPON EFFECTSWEAPON OVERVIEW EFFECTS FINAL REPORT ABOUT THE GICHD AND THE PROJECT The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) is an expert organisation working to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards, in close partnership with states, the UN and other human security actors. Based at the Maison de la paix in Geneva, the GICHD employs around 55 staff from over 15 countries with unique expertise and knowledge. Our work is made possible by core contributions, project funding and in-kind support from more than 20 governments and organisations. Motivated by its strategic goal to improve human security and equipped with subject expertise in explosive hazards, the GICHD launched a research project to characterise explosive weapons. The GICHD perceives the debate on explosive weapons in populated areas (EWIPA) as an important humanitarian issue. The aim of this research into explosive weapons characteristics and their immediate, destructive effects on humans and structures, is to help inform the ongoing discussions on EWIPA, intended to reduce harm to civilians. The intention of the research is not to discuss the moral, political or legal implications of using explosive weapon systems in populated areas, but to examine their characteristics, effects and use from a technical perspective. The research project started in January 2015 and was guided and advised by a group of 18 international experts dealing with weapons-related research and practitioners who address the implications of explosive weapons in the humanitarian, policy, advocacy and legal fields. This report and its annexes integrate the research efforts of the characterisation of explosive weapons (CEW) project in 2015-2016 and make reference to key information sources in this domain. -

Former Warsaw Pact Ammunition Handbook, Vol 3

NATO Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence FORMER WARSAW PACT AMMUNITION HANDBOOK VOLUME 3 Air Forces Ammunition Aerial projectiles, bombs, rockets and missiles TRENČÍN 2019 Slovak Republic For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence FORMER WARSAW PACT AMMUNITION HANDBOOK VOLUME 3 Air Forces Ammunition Aerial projectiles, bombs, rockets and missiles For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence The NATO Explosive Ordnance Centre of Excellence (NATO EOD COE) supports the efforts of the Alliance in the areas of training and education, information sharing, doctrine development and concepts validation. Published by NATO EOD Centre of Excellence Ivana Olbrachta 5, 911 01,Trenčín, Slovak Republic Tel. + 421 960 333 502, Fax + 421 960 333 504 www.eodcoe.org Former Warsaw Pact Ammunition Handbook VOL 3 – Edition II. ISBN 978-80-89261-81-9 © EOD Centre of Excellence. All rights reserved 2019 No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews. For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence Foreword Even though in areas of current NATO operations the insurgency is vastly using the Home Made Explosive as the main charge for emplaced IEDs, our EOD troops have to cope with the use of the conventional munition in any form and size all around the world. To assist in saving EOD Operators’ lives and to improve their effectiveness at munition disposal, it is essential to possess the adequate level of experience and knowledge about the respective type of munition. -

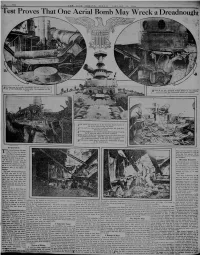

Test Proves That One Aerial Bomb Maywreck a Dreadnought

" " " * v " **. ^»*i>l-' J U ill/ A 1 LIB, , il.iiM Altl ¿ ¿ , 1 íJ ¿ 1 I I_.' ___ _ Test Proves That One Aerial Bomb May Wreck a Dreadnought A LL that was left of the wheelhouse and the forward fun- **¦ nel of the battleship Indiana after the explosion of the bomb '"TI/RECK of the forward 8-inch turret of the Indiana, j against tvhich the 900-pound bomb ivas exploded F "" smmsMsmsssssssssssimsmssMsssssssMswsMSSMsWSMsss^ rVHE bomb was the ¦*¦ placed aft of forward 8-inch turret at the point indicated by the arrmo i ; A T the left is a view of the vessel the amidships> first deck { .,.** being blown away \ A T THE right is a view of the second deck looking forward, ^ the X showing where the bomb exploded j ITHE picture at the lower left hand show's the third deck and -* the ammunition hoist. Had the ship been in commission the magazine probably ivould have been exploded j AT the lower hand is shown the **¦ right destruction wrought I on the fourth deck I _..-..__ ____-.... < By Quarterdeck THE seven pictures on this page there, and the campaign could not suffice to show the destruc¬ have been undertaken at all if th« tive effect of a bomb, not only Turks had been supplied with ar- on the upper works of a air force, not to speak of submarine* battleship, and bot upon the lower decks as well. torpedoes. In this case the target was the Discussion Demanded old battleship Indiana, formerly This article is not sensational It commanded by Captain H. -

NEEDLESS DEATHS in the GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During The

NEEDLESS DEATHS IN THE GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During the Air Campaign and Violations of the Laws of War A Middle East Watch Report Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 November 1991 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Cover design by Patti Lacobee Watch Committee Middle East Watch was established in 1989 to establish and promote observance of internationally recognized human rights in the Middle East. The chair of Middle East Watch is Gary Sick and the vice chairs are Lisa Anderson and Bruce Rabb. Andrew Whitley is the executive director; Eric Goldstein is the research director; Virginia N. Sherry is the associate director; Aziz Abu Hamad is the senior researcher; John V. White is an Orville Schell Fellow; and Christina Derry is the associate. Needless deaths in the Gulf War: civilian casualties during the air campaign and violations of the laws of war. p. cm -- (A Middle East Watch report) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-56432-029-4 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991--United States. 2. Persian Gulf War, 1991-- Atrocities. 3. War victims--Iraq. 4. War--Protection of civilians. I. Human Rights Watch (Organization) II. Series. DS79.72.N44 1991 956.704'3--dc20 91-37902 CIP Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch is composed of Africa Watch, Americas Watch, Asia Watch, Helsinki Watch, Middle East Watch and the Fund for Free Expression. The executive committee comprises Robert L. Bernstein, chair; Adrian DeWind, vice chair; Roland Algrant, Lisa Anderson, Peter Bell, Alice Brown, William Carmichael, Dorothy Cullman, Irene Diamond, Jonathan Fanton, Jack Greenberg, Alice H. -

The Art of Strafing

The Art of Strafing By Richard B.H. Lewis ODERN fighter pilots risk their lives Mevery day performing the act of strafing, which to some may seem like a tactic from a bygone era. Last Novem- ber, an F-16 pilot, Maj. Troy L. Gilbert, died strafing the enemy in Iraq, trying Painting by Robert Bailey to protect coalition forces taking fire on the ground. My first thought was, “Why was an F-16 doing that mission?” But I already knew the answer. In the 1980s, at the height of the Cold War, I was combat-ready in the 512th Fighter Squadron, an F-16 unit at Ramstein AB, Germany. We had to maintain combat status in air-to- air, air-to-ground, and nuclear strike operations. We practiced strafing oc- casionally. We were not very good at it, but it was extremely challenging. There is a big difference between was “Gott strafe England” (“God punish flight controls and a 30 mm Gatling flying at 25,000 feet where you have England”). The term caught on. gun. I have seen the aircraft return from plenty of room to maneuver and you In the World War I Battle of St. Mihiel, combat with one engine and major parts can barely see a target, and at 200 feet, Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker once strafed of a wing and flight controls blown off. where the ground is rushing right below eight German artillery pieces, each Unquestionably, the A-10 is the ultimate you and you can read the billboards drawn by a team of six horses. -

Air-To-Ground Battle for Italy

Air-to-Ground Battle for Italy MICHAEL C. MCCARTHY Brigadier General, USAF, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 2004 Air University Library Cataloging Data McCarthy, Michael C. Air-to-ground battle for Italy / Michael C. McCarthy. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-128-7 1. World War, 1939–1945 — Aerial operations, American. 2. World War, 1939– 1945 — Campaigns — Italy. 3. United States — Army Air Forces — Fighter Group, 57th. I. Title. 940.544973—dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112–6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix INTRODUCTION . xi Notes . xiv 1 GREAT ADVENTURE BEGINS . 1 2 THREE MUSKETEERS TIMES TWO . 11 3 AIR-TO-GROUND BATTLE FOR ITALY . 45 4 OPERATION STRANGLE . 65 INDEX . 97 Photographs follow page 28 iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Foreword The events in this story are based on the memory of the author, backed up by official personnel records. All survivors are now well into their eighties. Those involved in reconstructing the period, the emotional rollercoaster that was part of every day and each combat mission, ask for understanding and tolerance for fallible memories. Bruce Abercrombie, our dedicated photo guy, took most of the pictures. -

“Troops in Contact”

“Troops in Contact” Airstrikes and Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-362-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org September 2008 1-56432-362-5 “Troops in Contact” Airstrikes and Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan Map of Afghanistan ............................................................................................................ 1 I. Summary......................................................................................................................2 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................7 Methodology ................................................................................................................. -

HELP from ABOVE Air Force Close Air

HELP FROM ABOVE Air Force Close Air Support of the Army 1946–1973 John Schlight AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM Washington, D. C. 2003 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schlight, John. Help from above : Air Force close air support of the Army 1946-1973 / John Schlight. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Close air support--History--20th century. 2. United States. Air Force--History--20th century. 3. United States. Army--Aviation--History--20th century. I. Title. UG703.S35 2003 358.4'142--dc22 2003020365 ii Foreword The issue of close air support by the United States Air Force in sup- port of, primarily, the United States Army has been fractious for years. Air commanders have clashed continually with ground leaders over the proper use of aircraft in the support of ground operations. This is perhaps not surprising given the very different outlooks of the two services on what constitutes prop- er air support. Often this has turned into a competition between the two serv- ices for resources to execute and control close air support operations. Although such differences extend well back to the initial use of the airplane as a military weapon, in this book the author looks at the period 1946- 1973, a period in which technological advances in the form of jet aircraft, weapons, communications, and other electronic equipment played significant roles. Doctrine, too, evolved and this very important subject is discussed in detail. Close air support remains a critical mission today and the lessons of yesterday should not be ignored. This book makes a notable contribution in seeing that it is not ignored. -

The Politics and Ethics of Drone Bombing in Its Historical Context

The Politics and Ethics of Drone Bombing in its Historical Context Afxentis Afxentiou A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2018 To Marianna, for her love, support and patience 2 ABSTRACT This thesis intervenes in current debates concerning the violence of armed drones, developing a historical perspective on what is predominantly understood to be a novel form of warfare. It argues that debates on drones overlook the important linkages between drone warfare and earlier regimes of violence from the air. On the basis of a historical analysis of drone warfare, it offers a critique of drone bombing that goes beyond the narrative of “targeted killings”. The first part of this dissertation, comprising Chapter 1, introduces the central problematic of the thesis by revealing the crucial differences between, on the one hand, a description of drones strikes drawn from testimonies of people living under drones and, on the other, an account of these strikes based on the targeting methodology the U.S. military follows. This part demonstrates that the frame of “targeted killings” fails to offer an adequate lens through which the multifaceted violent effects of drone bombing can be explained, understood and criticised. The two chapters that constitute the second part of this thesis employ a genealogical historical method, demonstrating that the broader violent effects wrought by drone strikes – which testimonies reveal, but current military doctrine effaces – are intrinsically bound up with the development of the air weapon. More specifically, Chapter 2 offers a detailed account of the emergence of air power theory and discusses the doctrine of “strategic bombing”. -

Concept Plan for the Destruction of Eight Old Chemical Weapons

OPCW Executive Council Eighty-Fifth Session EC-85/NAT.2 11 – 14 July 2017 16 June 2017 ENGLISH Original: SPANISH PANAMA CONCEPT PLAN FOR THE DESTRUCTION OF EIGHT OLD CHEMICAL WEAPONS Background 1. The Republic of Panama has declared eight (8) old chemical weapons to be destroyed. The weapons are located on San José Island, off the Southern coast of Panama’s mainland. The eight chemical munitions are World War II-era and comprised of: six (6) M79, 1,000 lb. aerial bombs believed to contain the Schedule 3 toxic chemical phosgene (CG), also known as carbonyl dichloride; one (1) M78, 500 lb. aerial bomb believed to contain the Schedule 3 toxic chemical cyanogen chloride (CK); and one (1) M1A1 Cylinder, which has been confirmed empty and rusted through and which the Republic of Panama and the Technical Secretariat (hereinafter “the Secretariat”) of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) considered destroyed. All eight of these munitions were identified in the 2002 OPCW Technical Secretariat Final Inspection Report. 2. The Republic of Panama has determined that the seven bombs are unsafe to move because of their explosive configuration, age, and austere location. These characteristics were noted in the 2002 OPCW Technical Secretariat Final Inspection Report. Relocation would pose an undue risk to workers attempting to move them and to the environment. As such, the Republic of Panama plans to destroy the munitions in place. 3. The OPCW Secretariat agrees with the Republic of Panama’s assessment that there is no viable transportation option to remove the items for destruction elsewhere in the Republic of Panama or outside of the Republic of Panama. -

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron's

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron’s Experience during the Development of World War II Tactical Air Power by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 14, 2013 Keywords: World War II, fighter squadrons, tactical air power, P-47 Thunderbolt, European Theater of Operations Copyright 2013 by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce Approved by William Trimble, Chair, Alumni Professor of History Alan Meyer, Assistant Professor of History Mark Sheftall, Associate Professor of History Abstract During the years between World War I and World War II, many within the Army Air Corps (AAC) aggressively sought an independent air arm and believed that strategic bombardment represented an opportunity to inflict severe and dramatic damages on the enemy while operating autonomously. In contrast, working in cooperation with ground forces, as tactical forces later did, was viewed as a subordinate role to the army‘s infantry and therefore upheld notions that the AAC was little more than an alternate means of delivering artillery. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for a significantly expanded air arsenal and war plan in 1939, AAC strategists saw an opportunity to make an impression. Eager to exert their sovereignty, and sold on the efficacy of heavy bombers, AAC leaders answered the president‘s call with a strategic air doctrine and war plans built around the use of heavy bombers. The AAC, renamed the Army Air Forces (AAF) in 1941, eventually put the tactical squadrons into play in Europe, and thus tactical leaders spent 1943 and the beginning of 1944 preparing tactical air units for three missions: achieving and maintaining air superiority, isolating the battlefield, and providing air support for ground forces.