Jewish Apocalyptic and the Dead Sea Scrolls. the Ethel M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016)

James Block Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016) Contents ARISE OH YAH (Psalm 68) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AWAKE JERUSALEM (Isaiah 52) ................................................................................................................................... 4 BLESS YAHWEH OH MY SOUL (Psalm 103) ................................................................................................................ 5 CITY OF ELOHIM (Psalm 48) (Capo 1) .......................................................................................................................... 6 DANIEL 9 PRAYER .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 DELIGHT ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FATHER’S HEART ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 FIRSTBORN ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GREAT IS YOUR FAITHFULNESS (Psalm 92) ............................................................................................................. 11 HALLELUYAH -

Theme and Genre in 4Q177 and Its Scriptural Selections

THEME AND GENRE IN 4Q177 AND ITS SCRIPTURAL SELECTIONS Mark Laughlin and Shani Tzoref Jerusalem 4Q1771 has conventionally been classified as a “thematic pesher,”2 or, more recently as “thematic commentary,”3 or “eschatological midrash.”4 It is one of a group of Qumranic compositions in which the author cites and interprets biblical texts, applying them to the contemporary experience of his community, which he understands to be living in the eschatological era. Unlike the continuous pesharim, thematic pesha- rim are not structured as sequential commentaries on a particular 1 John M. Allegro first pieced together the thirty fragments that he identified as comprising 4Q177, which he labeled 4QCatena A. Cf. John M. Allegro and Arnold A. Anderson. Qumran Cave 4.I (4Q158–4Q186) (DJD V; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 67–74, Pls. XXIV–XXV. John Strugnell subsequently added four additional fragments, and suggested improvements to Allegro’s readings and reconstructions (“Notes en marge,” 236–48). Annette Steudel re-worked the order of the material in 4Q174 and 4Q177, and argued that the two manuscripts should be regarded as parts of a single composition, which she termed 4QMidrEschat. See George J. Brooke, “From Flori- legium or Midrash to Commentary: The Problem of Re/Naming an Adopted Manu- script,” in this volume. Cf. Annette Steudel, Der Midrasch zur Eschatologie aus der Qumrangemeinde (4QMidrEschata,b): Materielle Rekonstruktion, Textbestand, Gattung und traditionsgeschichtliche Einordnung des durch 4Q174 (“Florilegium”) und 4Q177 (“Catenaa”) repräsentierten Werkes aus den Qumranfunden (STDJ 13; Leiden: Brill, 1994). The current discussion will touch upon the relationship between 4Q177 and 4Q174 but is primarily concerned with the composition of 4Q177 itself. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Psalms 112-113 Page 1� of �7 M.K

Psalms 112-113 page 1! of !7 M.K. Scanlan Psalm 112 • Psalm 112 is a companion Psalm to Psalm 111. • It is also an acrostic Psalm with each verse or sentence beginning with a consecutive letter of the Hebrew alphabet. • This is one of the “hallel” psalms or Psalms of praise that either begins with or ends with “hallelujah!” • Psalm 111 ends with: (V: 10) Psalm 111:10 “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom; a good understanding have all those who do His commandments. His praise endures forever.” • Psalm 111 ends with the reverence or fear of the Lord and the doing of His commandments. • Psalm 112 talks about the man who has learned what it is to stand in the awe and reverence of God, it’s about that man who has committed himself to obeying God and doing His commandments. V: 1 Praise the Lord! Hallelujah! Once again this could be both a proclamation and or an exhortation. • Blessed, or “Oh how happy” is the man who fears the Lord - why? Because if you learn to fear the Lord truly, you will ultimately end up getting saved! Proverbs 14:27 “The fear of the Lord is a fountain of life, to turn one away from the snares of death.” Proverbs 19:23 “The fear of the Lord leads to life,…” • If we fear God, then we don’t need to fear anything, or anyone else! Ecclesiastes 12:13 “Fear God and keep His commandments, for this is the whole duty of man.” • The antidote to depression, to un-happiness, anxiety, and fear - is to praise the Lord, to fear Him, and to joyfully be obedient to what He’s instructed us to do. -

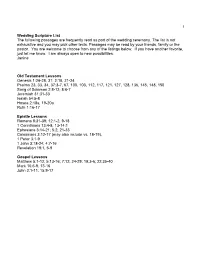

1 Wedding Scripture List the Following Passages Are Frequently Read As

1 Wedding Scripture List The following passages are frequently read as part of the wedding ceremony. The list is not exhaustive and you may pick other texts. Passages may be read by your friends, family or the pastor. You are welcome to choose from any of the listings below. If you have another favorite, just let me know. I am always open to new possibilities. Janine Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31; 2:18, 21-24 Psalms 23, 33, 34, 37:3-7, 67, 100, 103, 112, 117, 121, 127, 128, 136, 145, 148, 150 Song of Solomon 2:8-13; 8:6-7 Jeremiah 31:31-33 Isaiah 54:5-8 Hosea 2:18a, 19-20a Ruth 1:16-17 Epistle Lessons Romans 8:31-39; 12:1-2, 9-18 1 Corinthians 13:4-8, 13-14:1 Ephesians 3:14-21; 5:2, 21-33 Colossians 3:12-17 (may also include vs. 18-19). 1 Peter 3:1-9 1 John 3:18-24; 4:7-16 Revelation 19:1, 5-9 Gospel Lessons Matthew 5:1-12; 5:13-16; 7:12, 24-29; 19:3-6; 22:35-40 Mark 10:6-9, 13-16 John 2:1-11; 15:9-17 2 Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31 Then God said, "Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth." So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. -

JEWISH PRINCIPLES of CARE for the DYING JEWISH HEALING by RABBI AMY EILBERG (Adapted from "Acts of Laving Kindness: a Training Manual for Bikur Holim")

A SPECIAL EDITION ON DYING WINTER 2001 The NATIONAL CENTER for JEWISH PRINCIPLES OF CARE FOR THE DYING JEWISH HEALING By RABBI AMY EILBERG (adapted from "Acts of Laving Kindness: A Training Manual for Bikur Holim") ntering a room or home where death is a gone before and those who stand with us now. Epresence requires a lot of us. It is an intensely We are part of this larger community (a Jewish demanding and evocative situation. It community, a human community) that has known touches our own relationship to death and to life. death and will continue to live after our bodies are It may touch our own personal grief, fears and gone-part of something stronger and larger than vulnerability. It may acutely remind us that we, death. too, will someday die. It may bring us in stark, Appreciation of Everyday Miracles painful confrontation with the face of injustice Quite often, the nearness of death awakens a when a death is untimely or, in our judgement, powerful appreciation of the "miracles that are with preventable. If we are professional caregivers, we us, morning, noon and night" (in the language of may also face feelings of frustration and failure. the Amidah prayer). Appreciation loves company; Here are some Jewish principles of care for the we only need to say "yes" when people express dying which are helpful to keep in mind: these things. B'tselem Elohim (created in the image of the Mterlife Divine) Unfortunately, most Jews have little knowledge This is true no matter what the circumstances at of our tradition's very rich teachings on life after the final stage of life. -

Selah: Stop, Look, Listen – May 5, 2020

Water From Rock Selah: Stop, Look, Listen – May 5, 2020 The Lord be with you. Tell me, are you feeling a bit confused today? Maybe a little nervous. What with all the news about the coronavirus I mean, are we at the front end of the wave or at the back end? Will a face mask become an everyday accessory? Are they gonna take your temperature before you enter church service when it's only gonna be 25% full? We are facing a lot of unknowns, aren't we? And what they're calling the new normal... Well, it might really be a... Now, normal because everyday is different, it can be discouraging. But I was actually encouraged this week I was encouraged, and spending time in the Psalms and to realize that God's people did not have to understand everything that is happening, or where it is all leading before we can begin to seize the opportunity in it and to embrace the future with a Psalmist confidence and hope. I am today, pondering Psalm 37, that is a Psalm of David. It might be one of David's last Psalms because he says he's writing it as an old man in verse 25, David says, I have been young. And now, an old yet, I have not seen the righteous forsaken. Psalm 37 is the words of a man who has lived much and done much the words of a man who was sin greatly and been greatly forgiven. And all the ups and downs of life have not soured David, but they had quieted him and still his confidence as David has learned to see God in everything. -

Psalm 37 — Don’T Fret

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2004 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 37 — Don’t Fret 1.0 Introducing Psalm 37 See the Introduction for Psalm 36 for the relationships between Psalms 35–37. Psalm 37:11 appears to have been the source for the Third Beatitude in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:5, “Blessed are the gentle [or, meek], for they shall inherit the earth”). Psalm 37 is an acrostic psalm, with a consecutive letter of the Hebrew alphabet being the first letter of every other verse. See Psalms 9–10, 25, and 34. The next acrostic psalm will be Psalm 111. This psalm was written by David in his old age (verse 25). It is a fitting sequel to Psalm 36, which concluded with the visualization of judgment: There the doers of iniquity have fallen; They have been thrust down and cannot rise. 2.0 Reading Psalm 37 (NAU) A Psalm of David. a 37:1 Do not fret because of evildoers, Be not envious toward wrongdoers. 37:2 For they will wither quickly like the grass And fade like the green herb. b 37:3 Trust in the LORD and do good; Dwell in the land and cultivate faithfulness. Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs 2 Barrick, Placerita Baptist Church 2004 37:4 Delight yourself in the LORD; And He will give you the desires of your heart. g 37:5 Commit your way to the LORD; Trust also in Him, and He will do it. -

Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn Marquette University Recommended Citation Dunn, Steven, "Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures" (2009). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 13. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/13 Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures By Steven Dunn, B.A., M.Div. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2009 ABSTRACT Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn, B.A., M.Div. Marquette University, 2009 This study examines the pervasive influence of post-exilic wisdom editors and writers in the shaping of the Psalter by analyzing the use of wisdom elements—vocabulary, themes, rhetorical devices, and parallels with other Ancient Near Eastern wisdom traditions. I begin with an analysis and critique of the most prominent authors on the subject of wisdom in the Psalter, and expand upon previous research as I propose that evidence of wisdom influence is found in psalm titles, the structure of the Psalter, and among the various genres of psalms. I find further evidence of wisdom influence in creation theology, as seen in Psalms 19, 33, 104, and 148, for which parallels are found in other A.N.E. wisdom texts. In essence, in its final form, the entire Psalter reveals the work of scribes and teachers associated with post-exilic wisdom traditions or schools associated with the temple. -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal -

The Sweet Selah Moments Podcast. We Hope This Little Pause in Your Day Refreshes and Encourages You Friend

Speaker 1 (00:00): Welcome to the Sweet Selah moments podcast. We hope this little pause in your day refreshes and encourages you friend. Let's take time to know God through his word and love him more and more. This Sweet Selah moments podcast is brought to you by Word Radio and Sweet Selah Ministries. Nicole (00:21): Welcome to episode 48, Shh Be Quiet. Well, this is an interesting title, Sharon. It's not often quiet at my house. I actually really thought it would get at least a little quieter during the day at my house since three of my girls are finally back in school full-time, but ... with a very chatty four-year-old at home still and a seven month old puppy who just discovered she can bark, silence is still a very rare gift. Sharon (00:46): It is indeed. Nicole (00:46): It is! Sharon how's life at your house? Sharon (00:50): Well, I don't have chattering girls living here anymore, although my two could chat up a storm, but I do have a noisy puppy who thinks she owns the street outside. Oh my word. She sits on the couch. She looks out the window and she gets highly offended if someone else walks on our street. Nicole (01:07): Oh, she's so cute. Sharon (01:07): Oh, for crying out loud, I'm like, Bella, you don't own the street. Nicole (01:10): Right. Sharon (01:11): You can tell me when the UPS man comes in the driveway, I actually like to know that, but we don't need to know when anybody walks by. -

Psalm 121 Commentary

Psalm 121 Commentary PSALM 119 PSALMS Psalm 121 1 (A Song of Ascents.) I Will lift up my eyes to the mountains; From whence shall my help come? 2 My help comes from the LORD, Who made heaven and earth. 3 He will not allow your foot to slip; He who keeps you will not slumber. 4 Behold, He who keeps Israel Will neither slumber nor sleep. 5 The LORD is your keeper; The LORD is your shade on your right hand. 6 The sun will not smite you by day, Nor the moon by night. 7 The LORD will protect you from all evil; He will keep your soul. 8 The LORD will guard your going out and your coming in From this time forth and forever. INDUCTIVE BIBLE STUDY EXERCISE BEFORE YOU CONSULT THE COMMENTARY ON PSALM 121 Need "Help"? Click and meditate on… Jehovah Ezer: The LORD our Helper Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir's version "My Help" Study the Comments on Psalm 121 (below) Do a Greek/Hebrew Word Study on Help Commentaries on the Psalms Before you read the notes on Psalm 121, consider performing a simple Inductive Study on this great Psalm, so that you might experience the joy of personal discovery of its rich treasures. If you take time to do this before you read the comments, you will be pleasantly surprised how much illumination your Teacher, the Holy Spirit will provide (1Jn 2:20, 27, 1Cor 2:10-16 - and you will be better able to comment on the commentaries even as the Bereans "commented" on what Paul taught them in Acts 17:11-note).