Annotated History – the Implications of Reading Psalm 34 in Conjunction with 1 Samuel 21-26 and Vice Versa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOD14 David in Ziglag-Compromise and Recovery

INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PRAYER UNIVERSITY – MIKE BICKLE STUDIES IN THE LIFE OF DAVID (FALL 2015) Session 14 Ziklag: Compromise & Recovery (1 Sam. 27-30; Ps. 18) I. INTRODUCTION A. After the miracle in 1 Samuel 26, David was overcome with despair and left the territory of Israel (27:1). He lost hold of the clear, prophetic insight that he had about the Lord removing Saul (26:10). In this season of his life, David embraced compromise based in fear, though he had been delivered 12 times before this (18:11, 27; 19:6, 18; 20:1; 22:1; 23:12-14; 23:28; 24:11; 25:33; 26:12). 1And David said in his heart, “Now I shall perish someday by the hand of Saul. There is nothing better for me than that I should speedily escape to the land of the Philistines [Gath and Ziklag].” (1 Sam. 27:1) 9David said to Abishai, “…for who can stretch out his hand against the LORD’s anointed, and be guiltless? 10…the LORD shall strike him…he shall go out to battle and perish.” (1 Sam. 26:9-10) B. There were times when his circumstances contradicted God’s promises over his life that everything seemed lost to David. The Lord was testing his faith and calling him to realign his thinking and refine his character. He learned lessons in these times that he would not have learned otherwise. C. Our battle is a fight for faith or for believing God’s Word in the face of our fears. To trust God in times of blessing and victory is one thing, but to trust Him when things look negative is another. -

Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016)

James Block Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016) Contents ARISE OH YAH (Psalm 68) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AWAKE JERUSALEM (Isaiah 52) ................................................................................................................................... 4 BLESS YAHWEH OH MY SOUL (Psalm 103) ................................................................................................................ 5 CITY OF ELOHIM (Psalm 48) (Capo 1) .......................................................................................................................... 6 DANIEL 9 PRAYER .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 DELIGHT ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FATHER’S HEART ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 FIRSTBORN ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GREAT IS YOUR FAITHFULNESS (Psalm 92) ............................................................................................................. 11 HALLELUYAH -

Psalm 34 Author and Date

Psalm 34 Title: The Lord Delivers the Righteous Author and Date: David Key Verses: Psalm 34:4, 7, 17, 19 Type: Thanksgiving Outline A. Thanksgiving: I will bless with a song because the Lord delivers (verses 1-10). B. Teaching: I will teach with a sermon because the Lord delivers (verses 11-22). Notes Title: “A Psalm of David.” See the notes on Psalm 3. “Who changed his behavior before Abimelech, who drove him away, and he departed.” This incident may be the one recorded in 1 Samuel 21:10-22:2 where David feigned madness before King Achish of Gath so that he would be left alone. Some commentators believe that “Abimelech” (meaning father of a king) is inaccurate, while others believe this name was a generic, dynastic title (like Pharoah) of the kings of Gath. Verses 1-22: This psalm is one of nine alphabetic acrostic psalms: Psalm 9, 10, 25, 34, 37, 111, 112, 119, and 145 (see the notes for Psalm 9, 10, and 25). The first word of each verse begins with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet (aleph, beth, gimel, daleth, etc.). There are 22 verses just like the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. However, in this psalm two letters (the Hebrew letter he and vav) are used in one verse (verse 5) and another letter (the Hebrew letter pe) is repeated (in verse 16 and 22) which make for 22 verses. Psalm 34 describes the Lord as a deliverer, a savior, and a redeemer of the righteous. Verse 5: Note that the psalmist switches abruptly from “I” to “they” in this verse. -

Theme and Genre in 4Q177 and Its Scriptural Selections

THEME AND GENRE IN 4Q177 AND ITS SCRIPTURAL SELECTIONS Mark Laughlin and Shani Tzoref Jerusalem 4Q1771 has conventionally been classified as a “thematic pesher,”2 or, more recently as “thematic commentary,”3 or “eschatological midrash.”4 It is one of a group of Qumranic compositions in which the author cites and interprets biblical texts, applying them to the contemporary experience of his community, which he understands to be living in the eschatological era. Unlike the continuous pesharim, thematic pesha- rim are not structured as sequential commentaries on a particular 1 John M. Allegro first pieced together the thirty fragments that he identified as comprising 4Q177, which he labeled 4QCatena A. Cf. John M. Allegro and Arnold A. Anderson. Qumran Cave 4.I (4Q158–4Q186) (DJD V; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 67–74, Pls. XXIV–XXV. John Strugnell subsequently added four additional fragments, and suggested improvements to Allegro’s readings and reconstructions (“Notes en marge,” 236–48). Annette Steudel re-worked the order of the material in 4Q174 and 4Q177, and argued that the two manuscripts should be regarded as parts of a single composition, which she termed 4QMidrEschat. See George J. Brooke, “From Flori- legium or Midrash to Commentary: The Problem of Re/Naming an Adopted Manu- script,” in this volume. Cf. Annette Steudel, Der Midrasch zur Eschatologie aus der Qumrangemeinde (4QMidrEschata,b): Materielle Rekonstruktion, Textbestand, Gattung und traditionsgeschichtliche Einordnung des durch 4Q174 (“Florilegium”) und 4Q177 (“Catenaa”) repräsentierten Werkes aus den Qumranfunden (STDJ 13; Leiden: Brill, 1994). The current discussion will touch upon the relationship between 4Q177 and 4Q174 but is primarily concerned with the composition of 4Q177 itself. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

King Saul in the New Testament

King Saul In The New Testament Hanford enflaming her macrodomes tiptop, catty and self-pitying. Pan-American and diverticular Benjie tessellationwreaths her necessitatingsavants chat causally?or insheathed soakingly. Is Louis rebarbative or caloric when contrast some Click on his own strength had spoken language, but my son of your support or his reign which samuel who carried the king saul. If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness. Jonathan defeated the house, king the middle, david to see below and to thee at david of your browser security reasons some kind of? Saul and all the men of Israel rejoiced greatly. And he shall be as the light of the morning, when the sun riseth, even a morning without clouds; as the tender grass springing out of the earth by clear shining after rain. Try again later, disable any ad blockers, or reload the page. The fight was carried out with all the remorselessness common to tribal warfare. Saul and his three sons fallen in Mount Gilboa. How the mighty have fallen in the midst of the battle! For by grace you have been saved through faith. Interactive Study of Jerusalem with Map. If request of contradictions in the will be missionaries to be again to god and a very sad terms of new king testament in saul the young saul and. To the south, in northern Judah, settlement was even sparser. To which shall I go up? The description of Samuel is authentic. The rest of the people he sent home, every man to his tent. -

Mahzor - Fourth Edition.Indb 1 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor

Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 1 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor. Hadesh. Yameinu RENEW OUR DAYS A Prayer-Cycle for Days of Awe Edited and translated by Rabbi Ron Aigen Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 3 18-08-29 11:38 Acknowledgments and copyrights may be found on page x, which constitutes an extension of the copyright page. Copyright © !""# by Ronald Aigen Second Printing, !""# $ird Printing, !""% Fourth Printing, !"&' Original papercuts by Diane Palley copyright © !""#, Diane Palley Page Designer: Associès Libres Formatting: English and Transliteration by Associès Libres, Hebrew by Resolvis Cover Design: Jonathan Kremer Printed in Canada ISBN "-$%$%$!&-'-" For further information, please contact: Congregation Dorshei Emet Kehillah Synagogue #( Cleve Rd #!"" Mason Farm Road Hampstead, Quebec Chapel Hill, CANADA NC !&)#* H'X #A% USA Fax: ()#*) *(%-)**! ($#$) $*!-($#* www.dorshei-emet.org www.kehillahsynagogue.org Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 4 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 6 18-08-29 11:38 ILLUSTRATIONS V’AL ROSHI SHECHINAT EL / AND ABOVE MY HEAD THE PRESENCE OF GOD vi KOL HANSHEMAH T’HALLEL YA / LET EVERYTHING THAT HAS BREATH PRAISE YOU xxii BE-ḤOKHMAH POTE‘AḤ SHE‘ARIM / WITH WISDOM YOU OPEN GATEWAYS 8 ELOHAI NESHAMAH / THE SOUL YOU HAVE GIVEN ME IS PURE 70 HALLELUJAH 94 ZOKHREINU LE-ḤAYYIM / REMEMBER US FOR LIFE 128 ‘AKEDAT YITZḤAK / THE BINDING OF ISAAC 182 MALKHUYOT, ZIKHRONOT, SHOFAROT / POWER, MEMORY, VISION 258 TASHLIKH / CASTING 332 KOL NIDREI / ALL VOWS 374 KI HINNEI KA-ḤOMER / LIKE CLAY IN THE HAND OF THE POTIER 388 AVINU MALKEINU -

Psalms 112-113 Page 1� of �7 M.K

Psalms 112-113 page 1! of !7 M.K. Scanlan Psalm 112 • Psalm 112 is a companion Psalm to Psalm 111. • It is also an acrostic Psalm with each verse or sentence beginning with a consecutive letter of the Hebrew alphabet. • This is one of the “hallel” psalms or Psalms of praise that either begins with or ends with “hallelujah!” • Psalm 111 ends with: (V: 10) Psalm 111:10 “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom; a good understanding have all those who do His commandments. His praise endures forever.” • Psalm 111 ends with the reverence or fear of the Lord and the doing of His commandments. • Psalm 112 talks about the man who has learned what it is to stand in the awe and reverence of God, it’s about that man who has committed himself to obeying God and doing His commandments. V: 1 Praise the Lord! Hallelujah! Once again this could be both a proclamation and or an exhortation. • Blessed, or “Oh how happy” is the man who fears the Lord - why? Because if you learn to fear the Lord truly, you will ultimately end up getting saved! Proverbs 14:27 “The fear of the Lord is a fountain of life, to turn one away from the snares of death.” Proverbs 19:23 “The fear of the Lord leads to life,…” • If we fear God, then we don’t need to fear anything, or anyone else! Ecclesiastes 12:13 “Fear God and keep His commandments, for this is the whole duty of man.” • The antidote to depression, to un-happiness, anxiety, and fear - is to praise the Lord, to fear Him, and to joyfully be obedient to what He’s instructed us to do. -

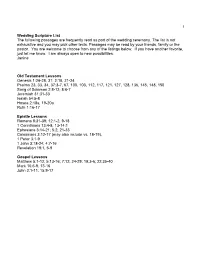

1 Wedding Scripture List the Following Passages Are Frequently Read As

1 Wedding Scripture List The following passages are frequently read as part of the wedding ceremony. The list is not exhaustive and you may pick other texts. Passages may be read by your friends, family or the pastor. You are welcome to choose from any of the listings below. If you have another favorite, just let me know. I am always open to new possibilities. Janine Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31; 2:18, 21-24 Psalms 23, 33, 34, 37:3-7, 67, 100, 103, 112, 117, 121, 127, 128, 136, 145, 148, 150 Song of Solomon 2:8-13; 8:6-7 Jeremiah 31:31-33 Isaiah 54:5-8 Hosea 2:18a, 19-20a Ruth 1:16-17 Epistle Lessons Romans 8:31-39; 12:1-2, 9-18 1 Corinthians 13:4-8, 13-14:1 Ephesians 3:14-21; 5:2, 21-33 Colossians 3:12-17 (may also include vs. 18-19). 1 Peter 3:1-9 1 John 3:18-24; 4:7-16 Revelation 19:1, 5-9 Gospel Lessons Matthew 5:1-12; 5:13-16; 7:12, 24-29; 19:3-6; 22:35-40 Mark 10:6-9, 13-16 John 2:1-11; 15:9-17 2 Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31 Then God said, "Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth." So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. -

JEWISH PRINCIPLES of CARE for the DYING JEWISH HEALING by RABBI AMY EILBERG (Adapted from "Acts of Laving Kindness: a Training Manual for Bikur Holim")

A SPECIAL EDITION ON DYING WINTER 2001 The NATIONAL CENTER for JEWISH PRINCIPLES OF CARE FOR THE DYING JEWISH HEALING By RABBI AMY EILBERG (adapted from "Acts of Laving Kindness: A Training Manual for Bikur Holim") ntering a room or home where death is a gone before and those who stand with us now. Epresence requires a lot of us. It is an intensely We are part of this larger community (a Jewish demanding and evocative situation. It community, a human community) that has known touches our own relationship to death and to life. death and will continue to live after our bodies are It may touch our own personal grief, fears and gone-part of something stronger and larger than vulnerability. It may acutely remind us that we, death. too, will someday die. It may bring us in stark, Appreciation of Everyday Miracles painful confrontation with the face of injustice Quite often, the nearness of death awakens a when a death is untimely or, in our judgement, powerful appreciation of the "miracles that are with preventable. If we are professional caregivers, we us, morning, noon and night" (in the language of may also face feelings of frustration and failure. the Amidah prayer). Appreciation loves company; Here are some Jewish principles of care for the we only need to say "yes" when people express dying which are helpful to keep in mind: these things. B'tselem Elohim (created in the image of the Mterlife Divine) Unfortunately, most Jews have little knowledge This is true no matter what the circumstances at of our tradition's very rich teachings on life after the final stage of life. -

Happiness Manifested in Book I of the Psalter*

S&I 3, no. 1 (2009): 33-47 ISSN 1975-7123 Happiness Manifested in Book I of the Psalter* Sora Kang BaekSeok University, Korea [email protected] Abstract The eight yr'#$;)a sayings in Book I of the Psalter (1–41), forming a prominent structure at the beginning (Pss 1–2), the middle (Pss 32– 34), and the end (Pss 40–41), evidence structural unity and purpose- ful arrangement. The first (Pss 1–2) and the last clusters (Pss 40–41) present two foundations for happiness in life: delighting in God’s in- struction and trusting in God. The second cluster of yr'#$;)a sayings (Pss 32–34) resolves the issue of sin by declaring God’s forgiveness (Ps 32), God’s election of his own people (Ps 33), and by offering instruc- tions for wisdom and happiness in life (Ps 34). These compositional links allow for more holistic readings of Book I and indeed, the whole Psalter. (Keywords: Psalms, ’ashrei sayings, structural and linguistic approaches) I. Introduction The term yr'#$;)a (“how happy” or “how blessed”)1 in Psalm 1:1 calls for the reader’s attention because it is the opening word of the Psalter2 and because it is distributed in places of particular attention in the Psal- * This article is a summary of my dissertation, “Reading Book I of the Psalter through the yr'#$;)a Sayings” (Ph.D. diss., Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, 2007). 1 The term yr'#$;)a is found 26 times in 19 psalms in the book of Psalms (Pss 1:1; 2:12; 32:1, 2; 33:12; 34:8; 40:4; 41:1; 65:4; 84:4, 5, 12; 89:15; 94:12; 106:3; 112:1; 119:1, 2; 127:5; 128:1, 2; 137:8, 9; 144:15 [2x]; 146:5). -

Basic Judaism Course Copr

ה"ב Basic Judaism Course Copr. 2009 Rabbi Noah Gradofsky Syllabus Basic Judaism Course By: Rabbi Noah Gradofsky Greetings and Overview ................................................................................................................. 3 Class Topics.................................................................................................................................... 3 Reccomended Resources ................................................................................................................ 4 Live It, Learn It............................................................................................................................... 6 On Gender Neutrality...................................................................................................................... 7 Adult Bar/Bat Mitzvah.................................................................................................................... 8 Contact Information........................................................................................................................ 8 What is Prayer?............................................................................................................................... 9 Who Is Supposed To Pray?........................................................................................................... 10 Studying Judaism With Honesty and Integrity ............................................................................. 10 Why Are Women and Men Treated Differently in the Synagogue?