Tobacco Trade Between Iran and Ottoman with the Emphasis on the Contracts of the Two Governments, in the Second Half of the Nine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

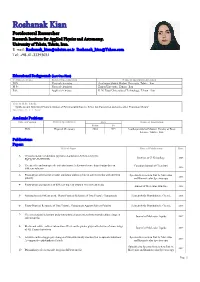

Roshanak Kian Postdoctoral Researcher Research Institute for Applied Physics and Astronomy, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

Roshanak Kian Postdoctoral Researcher Research Institute for Applied Physics and Astronomy, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Tel: +98-41-33393031 Educational Background: (Last One First) Certificate Degree Field of Specialization Name of Institution Attended PhD Physical chemistry Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University, Tabriz - Iran M.Sc. Physical chemistry Zanjan University, Zanjan - Iran B.Sc. Applied chemistry K. N. Toosi University of Technology, Tehran - Iran Title of M.Sc. Thesis: “ Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Pyridinocalix(4)arene Silver Ion Complexes and some other Transition Metals” Supervisors: Dr. A. A. Torabi Academic Positions: Title of Position Field of Specialization Date Name of Institution From To PhD Physical Chemistry 2010 2015 Azarbaijan Shahid Madani- Faculty of Basic Science, Tabriz - Iran. Publications: Papers: Title of Paper Place of Publication Date 1- Crystal structure of dichloro (pyridine-2-aldoxime-N,N)mercury(II): JOURNAL OF Z. Kristallogr 2005 HgCl2(NC5H4CHNOH) 2- The specific and non-specific solvatochromic behavior of some diazo Sudan dyes in Canadian Journal of Chemistry 2015 different solvents 3- Photo-physical behavior of some antitumor anthracycline in solvent media with different Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular 2014 polarity and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 4- Photo-physical properties of different types of vitamin A in solvent media Journal of Molecular Structure 2015 5- Solvatochromic Effects on the Photo-Physical -

Culturetalk Iran Video Transcripts: Azerbaijan Museum

CultureTalk Iran Video Transcripts: http://langmedia.fivecolleges.edu Azerbaijan Museum Persian transcript: نگار: ھَمين کﻻً تو اين قِ َسمت َمرکزی َشھر َوقتی پياده َروی کنی خيلی ساختِ ِمونھای[ساختمان ِھای ] قديمی می بينی که مثﻻً تبديل شدند حاﻻ...حاﻻ يه اِ ِستفاده ای دارند اَ َزش[ َاز آن] می حکنند َولی در ِعين ال موزه است و موزه ِی موزه ِی تبريز موزه ِی َآذربايجانه[ َآذربايجان است] اِ ِسمش. تو ھَمين ميدون[ميدان] َشھرداری تبريز يه کم باﻻتر از اون واقِع شده که ديگه َمثﻻً... محسن: موزه ِی َآذربايجان نگار: آره، ِ ِاسمش موزه ِی آذربايجانه . محسن: َيعنی چه چيزای[ ِچيزھای] ﱢخاصی تو اونجا[آنجا] ِنگه داری می شه[می شود] شما [ که می دانيد]. نگار: من خيلی ساﻻی[سال ھای] پيش رفتم ولی خب ِتوی... دو َ َ طبقه داره توی ََطبقه ِی باﻻش[ ِباﻻی آن] ُکﻻً َمثﻻً َ ّاوﻻً يه ِ سری يه ِسری چيزايی[چيزھايی] که َسنگايی[سنگ ھايی] که نوشته ھايی حاﻻ ھر چی... ُظروفی که از َ ّحفاری َ ِ ِمسجد کبود که... َ ِ ِمسجد کبود َدقيقاً َ َِبغل موزه ِی َآذربايجان ِواقع شده و اونجا ُکﻻً يه ِ َ قسمتی َمثﻻً ُ ِحدود بگم[بگويم] پنج شيش سال پيش يه ِ َقسمتی اونجا کشف کردند که َ َفھميدند که اين ِ َِقدمت خيلی چند ساله داشته زير خاک ُ ّکلی چيز پيدا کردند ُ ّکلی ِ ِ ِاسکلت َآدما[آدم ھا] رو[را] پيدا کردند ُ ّکلی َمثﻻً َھمين َظرفا َ ِانواع چيزا[چيزھا]. ُمحسن: َظرف ھا و ِ ِسکه ھا . نگار: اين ھا را پيدا کردند که َاصﻻً ُ ّکلی ُ َکمک کرد به ِ َ ِشناختن ِتاريخ اون ِ َقسمت. -

A Short Glimpse to the Urban Development of Tabriz During the History * Ph.D Candidate

Journal Of Contemporary Urban Affairs 2019, Volume 3, Number 1, pages 73– 83 A Short Glimpse to the Urban Development of Tabriz During the History * Ph.D Candidate. NARMIN BABAZADEH ASBAGH Faculty of Architecture, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] A B S T R A C T A R T I C L E I N F O: Article history: Locating on North West of Iran, Tabriz, the capital of East Azerbaijan Province, Received 03 September 2018 is one of the important metropolises of the country. The foundation of this Accepted 08 October 2018 Available online 26 October historic city dated back to 1500 B.C. but due to the severe earthquakes, few 2018 historic buildings remained from ancient eras. In 2012, Tabriz was selected as the most beautiful city of Iran, and it is nominated as the tourism capital of Keywords: Islamic countries in 2018. Tabriz used to be the capital of Iran during different Tabriz; dynasties like Ilkhanid, Kara Koyunlu, Ak Koyunlu, and Safavid; it was the Iran; Urban Development; residence of the royal family and crown prince during the Qajar Dynasty Qajar Dynasty; period. Tabriz is famous as “the city of the firsts”; and the Historic Bazaar Rapid Urban Growth. Complex of Tabriz is the biggest roofed bazaar in the world, inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 2010. Tabriz experiences the phenomenon of rapid urban growth causing the formation of slum settlements in the border zones of the city. This paper will briefly discuss the urban development of Tabriz during the history. -

Shahriyar: Shahriyar and “Sahandim”

Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 20 № 3 2017, 126-145 © Khazar University Press 2017 DOI: 10.5782/2223-2621.2017.20.3.126 Poetry Customs and Traditions of Shahriyar: Shahriyar and “Sahandim” Esmira Fuad (Shukurova) Institute of Literature named after Nizami Ganjavi, Azerbaijan National Academy of Science Introduction Regardless of any poetry model, in which the poetic thought is expressed, the poet is always his own time and century’s voice, its conscience, friend of his people, the protector of people who live frankly, not enticed of the world blessing and a heart, who speaks only the truth pertaining to his period, its wishes and intentions. One of the bearers of these passionate hearts is Doctor Seyid Mahammadhuseyn Behjat Tebrizi Shahriyar… Who is Shahriyar? Shahriyar is the most powerful representative of Iran and Azerbaijani poetry of 20-th century, the classical poet and art genius estimated as Hafizi-sani and Sadi of his time. He was born in Tabriz city on March 21, 1905, in spring. Haji Miraga Khoshginabi Musavi, the poet’s father was a well-known lawyer in Tabriz and his mother Kovkab khanim was a housewife. Haji Miraga, who has enjoyed universal esteem of his people, known as jack-of-all-trades, holding in high respect amongst the friends, at the same time being a protector of needy families and men was known as a personality taking care of truth. Shahriyar lived in the Southern Azerbaijan, Iran, during some stages of the 20-th century which was characterized by severe class struggles and social-political fights for the national freedom, cultural progress. -

Article a Catalog of Iranian Prostigmatic Mites of Superfamilies

Persian Journal of Acarology, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 389–474. Article A catalog of Iranian prostigmatic mites of superfamilies Raphignathoidea & Tetranychoidea (Acari) Gholamreza Beyzavi1*, Edward A. Ueckermann2 & 3, Farid Faraji4 & Hadi Ostovan1 1 Department of Entomology, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Fars, Iran; E-mail: [email protected] 2 ARC-Plant Protection Research Institute, Private bag X123, Queenswood, Pretoria, 0121, South Africa; E-mail: [email protected] 3 School of Environmental Sciences and Development, Zoology, North-West University- Potchefstroom Campus, Potchefstroom, 2520, South Africa 4 MITOX Consultants, P. O. Box 92260, 1090 AG Amsterdam, The Netherlands * Corresponding author Abstract This catalog comprises 56 genera and 266 species of mite names of superfamilies Raphignathoidea and Tetranychoidea recorded from Iran at the end of January, 2013. Data on the mite distributions and habitats based on the published information are included. Remarks about the incorrect reports and nomen nudum species are also presented. Key words: Checklist, mite, habitat, distribution, Iran. Introduction Apparently the first checklist about mites of Iran was that of Farahbakhsh in 1961. Subsequently the following lists were published: “The 20 years researches of Acarology in Iran, List of agricultural pests and their natural enemies in Iran, A catalog of mites and ticks (Acari) of Iran and Injurious mites of agricultural crops in Iran” are four main works (Sepasgosarian 1977; Modarres Awal 1997; Kamali et al. 2001; Khanjani & Haddad Irani-Nejad 2006). Prostigmatic mites consist of parasitic, plant feeding and beneficial predatory species and is the major group of Acari in the world. Untill 2011, 26205 species were described in this suborder, of which 4728 species belong to the cohort Raphignathina and tetranychoid and raphignathoid mites include 2211 and 877 species respectively (Zhang et al. -

Cigarette Smoking in Iran and Other Asian Countries: Results of Isfahan Cohort Study (Ics)

WCRJ 2018; 5 (4): e1168 A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON THE PREVALENCE AND RELATED FACTORS OF CIGARETTE SMOKING IN IRAN AND OTHER ASIAN COUNTRIES: RESULTS OF ISFAHAN COHORT STUDY (ICS) M. MOHAMMADIAN1, N. SARRAFZADEGAN2, H. REZA ROOHAFZA3, M. SADEGHI4, A. HASANZADEH5, M. REJALI6 1MSC in Epidemiology, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran 2Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Center, Cardiovascular Research Institute, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran 3Cardiac Rehabilitation Research Center, Cardiovascular Research Institute, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran 4Cardiac Rehabilitation Research Center, Cardiovascular Research Institute, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran 5Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran 6Epidemiologists, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran Abstract – Introduction: Cigarette smoking is one of the most well-known risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, cancers and pulmonary diseases. The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence of cigarette smoking and its related factors in central parts of Iran and compare the results with other Asian countries. Materials and Methods: The prevalence and related factors of cigarette smoking in central parts of Iran were determined using a population-based cohort study in Iran. Also, the prevalence -

The Use of the Naturalism Approach in Designing the Tabriz Carpet Museum

21 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.51148/jaas.2018.3 THE USE OF THE NATURALISM APPROACH IN DESIGNING THE TABRIZ CARPET MUSEUM Amir Rishi Jegheh and Ardalan Karimi Ilkhchi branch, Islamic Azad University, Ilkhchi, Iran ABSTRACT Culture and art have come from the very beginning of mankind, along with human life, Research Article in order to calm down humankind, and what comes out of mind in different arts and in different ways. With the advancement of mankind in various arenas and sciences, art, PII: S238315531800003-7 in turn, was subject to change and in various parts of the earth's human races, the craftsmanship of buildings and handicrafts was made in caves. Meanwhile, art in the Middle East from ancient times was the cradle of human civilization and the creator Received: 22 Aug. 2018 and developer of human beings in various fields, including art. From ancient times, Revised: 30 Nov. 2018 especially after the arrival of Islam, Iran has witnessed progress in various fields of Published: 15 Dec. 2018 literary culture, especially art and architecture. In addition to the art of building and architecture, the creation of motifs in the tiling of mosaics etc. Handmade carpet art is one of the characteristics of recognizing the art of the land of Iran, especially the territory of Azerbaijan. Tabriz is a Persian carpet garden with the texture and development of a variety of carpets in different designs with a fringe in the range and worldwide name in different parts of the world. It is worth mentioning that this ancient city has an exhibition or museums in which architecture along with art witnesses the display of authentic Iranian and Islamic art and architecture. -

Kerman Xv.—Xvi

KERMAN XV.—XVI. LANGUAGES 301 968. Robert Joseph Dillon, “Carpet Capitalism and the Trade of the Kerman Consular District for the Year Craft Involution in Kirman. Iran: A Study in Economic 1902-03 by Major P. Sykes, His Majesty’s Consul,” Anthropology,” Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1976. House of Commons Pari iamentary Papers, Annual Series Arthur Cecil Edwards, The Persian Carpet: A Survey of o f Trade Reports, Cd.1386, 1903. Idem, “Report for the the Carpet-Weaving Industry of Persia, London, 1975. Year 1905-06 on the Trade of the Kerman Consular Dis A. H. Gleadowe-Newcomen, Report on the Commercial trict,” House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, Annual Mission to South-Eastern Persia During 1904-1905, Series of Trade Reports, Cd.2682, 1906. Ahmad-'Ali Calcutta, 1906. James Gustafson, “Opium, Carpets, and Khan Waziri Kermani, Jografia-ye Kerman, ed. Moham- Constitutionalists: A Social History of the Elite House mad-Ebrahim Bastani Parizi, 2nd ed., Tehran, 1974. holds of Kirman, 1859-1914,” Ph.D. diss., University of Hans E. Wulff, The Traditional Crafts of Persia: Their Washington, 2010. Leonard Michael Helfgott, Ties that Development, Technology, and Influence on Eastern and Bind: A Social History o f the Iranian Carpet, Washing Western Civilization, London, 1966. ton, D.C., 1 994. L. Haworth, “Diary for the Week Ending (J a m e s M. G u s t a f s o n ) November 12 1905,” U. K. National Archives, Kew, F.O. 248/846. International Monetary Fund, Islamic Republic of Iran—Statistical Appendix, IMF Country Report No. 04/307, September, 2004. -

National Army Day Marked Sion-Making, the Top Diplomat Added

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13922 Monday APRIL 19, 2021 Farvardin 30, 1400 Ramadan 6, 1442 Envoy: Creating a ‘candid Iran freestyle wrestling Ayatollah Khamenei Iran–China cultural ties picture’ about lifting sanctions team crowned Asian donates $120,000 to drastically increased after pursued in Vienna Page 2 champions Page 3 free prisoners Page 7 Islamic Revolution Page 8 See page 3 60% enrichment carried important political messages: Ghalibaf TEHRAN— Mohammad Bagher Ghali- enemies that Iran’s nuclear industry has baf, speaker of the Iranian parliament, become indigenous and no one can stop spoke on Sunday about the 60% uranium the progress of Islamic Iran.” enrichment and the sabotage act at Na- Speaking at the parliament, Ghalibaf called tanz, suggesting that the sabotage must enrichment of uranium to 60% “an epoch-mak- be responded “at the right time”. ing” event in terms of science and technology Noting that enriching uranium up to in addition important political messages. 60% purity carried important political The April 11 sabotage attack on the messages to the West, Ghalibaf said, “Iran’s Natanz nuclear plant is an instance of enemies expected Iran’s nuclear activities war crime in terms of international law to be halted or slowed down by terrorist and the UN Charter. acts, but this enrichment proved to our Continued on page 2 Annual aluminum ingot production up 61% MBS TEHRAN - Production of aluminum ingot ovation Organization (IMIDRO) showed. -

Tabriz Historic Bazaar (Iran) No 1346

Rotterdam, 25–28 June 2007. Tabriz Historic Bazaar (Iran) Weiss, W. M., and Westermann, K. M., The Bazaar: Markets and Merchants of the Islamic World, Thames and Hudson No 1346 Publications, London, 1998. Technical Evaluation Mission: 13–16 August 2009 Additional information requested and received from the Official name as proposed by the State Party: State Party: ICOMOS sent a letter to the State Party on 19 October 2009 on the following issues: Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex • Further justification of the serial approach to the Location: nomination. • Further explanation of how the three chosen sites Province of East Azerbaijan relate to the overall outstanding value of the property and of how they are functionally linked, Brief description: with reference to the Goi Machid and the Sorkhāb Bazārchā areas, in relation to the wider Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex consists of a series of Bazaar area. interconnected, covered brick structures, buildings, and • enclosed spaces for different functions. Tabriz and its Expansion of the description of the legal th protection measures. Bazaar were already prosperous and famous in the 13 • century, when the town became the capital city of the Expansion of the description of the objectives country. The importance of Tabriz as a commercial hub and the measures of the planning instruments in continued until the end of the 18th century, with the force in relation to the factors threatening the expansion of Ottoman power. Closely interwoven with property. the architectural fabric is the social and professional • Further explanation of the overall framework of organization of the Bazaar, which allows its functioning the management system and of the state of and makes it into a single, integrated entity. -

An Analysison Urbansprawlinthe Tabriz Metropolitan and Its Fringe Cities

AN ANALYSISON URBANSPRAWLINTHE TABRIZ METROPOLITAN AND ITS FRINGE CITIES 1RASOULGHORBANI, 2MINA FAROKHISOMEH 1Professor in Department of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Tabriz , Tabriz, Iran. 2PhD Candidate of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract- This paper assessment causes and effects of urban sprawl development pattern in during 1984- 2011 in fringe cities of the Tabriz metropolitan Area. The sprawl is external growth without control and imbalance at around of urban area that caused of destruction green space, increase traffic, loss of agricultural land and changes it’s to built-up area. In order to detect and evaluate to measure the model of urban sprawl, density and Holderness model was employed. We used quantities data of the study area from the period between 1984 and 2011, and Population Censuses Data. The result of this study shows that economic, social and environmental effects of sprawl caused that change in agriculture land to built-up area, density and transportation system from 1984 to 2011 in the around of Tabriz. Density and area analysis show that there has been an increase growth in area during the 27 years with the Percentage growth in population by 1.43% in Basmenj, 1.62% in Sardrud, 2.67% in Sofyan and 1.98% in Tabriz and with the reduction of density from 1984 to 2011. The Holderness Equation indicates in the fringe of the metropolitan city of Tabriz that on average high percent of the city physical growth was due to some factors other than population growth, and some percent was due to population growth. -

Cigarette Smoking – a Threat to Development in Iran

WCRJ 2017; 4 (4): e968 LETTER TO THE EDITOR: CIGARETTE SMOKING – A THREAT TO DEVELOPMENT IN IRAN H.R. SADEGHI-GANDOMANI1, M. DERAKHSHANJAZARI2, H. SALEHINIYA1,3 1Zabol University of Medical Sciences, Zabol, Iran 2Department of Occupational Health, Neyshabur University of Medical Sciences, Neyshabur, Iran 3Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran KEYWORDS: Smoking, Development, Iran. Tobacco use is one of the major risk factors for the used to smoke8. Among men who smoke cigarette global burden of diseases (GBD) worldwide, espe- in Iran, 67% started smoking for the first time at cially in relation to chronic and non-communicable the age of 14 and 80% started cigarette smoking diseases (NCDs)1. So that 5 million people die annu- before the age of 209. ally due to tobacco consumption2. The prevalence of Findings from a national study conducted in cigarette smoking as a major health problem varies 2007 on 5287 individuals aged 15-64 in all Ira- from country to country3. In Iran, like in many other nian provinces showed that cigarette smoking developing countries, cigarette smoking is one of the is the most common form of smoking tobac- main concerns of the healthcare system4. co among Iranian men. In this study, the highest In Iran, cigarette smoking was started during amount of cigarette smoking was also observed in the reign of Shah Abbas, the fifth king of the Sa- the 45-64 age groups6. According to the results of favid dynasty (1579-1629). Then, it quickly spread the first survey study in 1991, cigarette smoking across the country, and in 1937, the first cigarette prevalence among Iranians aged 15-69 was 14.6% factory with the capacity of producing 600 million (27.2% in men and 3.4% in women)10.