CASE 15 Will They Populate the Boxes?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fax2mail User Guide

Fax2Mail User Guide Welcome to Fax2Mail. This guide is designed to provide new users with complete instructions on how to use this exciting service. Additional information can be found on our website at www.fax2mail.com. Thank you for choosing Fax2Mail. About Fax2Mail As a global leader and pioneer in multimedia messaging solutions, EasyLink uniquely combines the best features of fax technology and the convenience of email into one powerful and easy-to-use solution. Our Fax2Mail solution enables customers to seamlessly integrate the power of fax into their existing email service. Users can send, receive, save, file, forward and track faxes in seconds--right from their desktops--without having to convert file formats. Work is accomplished faster, with added security and total reliability. Fax2Mail works with our clients' existing platforms for Internet access and email. Traffic is forwarded through EasyLink Service's high-speed, high-volume network of servers with total transparency to end users. Virtually all common document files, spreadsheets and graphic image files are automatically converted to outbound faxes. Users also have the option of storing custom cover sheets for outbound fax deliveries. When a fax is received over our system, it is automatically forwarded to an assigned user's email box as a TIFF or PDF attachment with notification in the subject line. Clients maintain total control over administration of their accounts through Web-based user registration, coversheet selection/storage, billing and report options. Just choose the documents you want to transmit and attach them to email as you would normally. Send your message to [email protected] and we'll do the rest--converting the files for instant delivery as crystal-clear faxes! There are a variety of methods in which you can send and receive electronic faxes. -

Coremail Pro Email Hosting Webmail User Manual

Coremail Pro Email Hosting Webmail User Manual Website:http://www.coremail.hk/ Hotline:400-000-1631 Copyright Statement This document is copyrighted by Coremail Hong Kong Company Limited. All rights reserved. Without written permission, no company or individual may disclose, reprint, or otherwise distribute any part of this document to a third party. Otherwise, they will be held backupable. Disclaimer This document provides only phase information. The contents can be updated at any time based on the actual situation of the product without prior notice. Coremail is not liable for any direct or indirect losses caused by improper use of documents. Document update This document was last revised in Nov, 2019 by Coremail Hong Kong Limited Company. About US Company website http://www.coremail.cn Sales Consulting Hotline 400-000-1631 Technical Support Hotline 400-888-2488 Website:http://www.coremail.hk/ Hotline:400-000-1631 Content 1. Webmail Introduction.......................................................................................... 6 1.1 Webmail Log in............................................................................................................6 1.2 Webmail Page.............................................................................................................. 7 1.2.1 Navigation Bar........................................................................................................7 1.2.2 Shortcut Bar............................................................................................................8 -

SIM7000 Series Email Application Note

SIM7000 Series_Email _Application Note LPWA Module SIMCom Wireless Solutions Limited Building B, SIM Technology Building, No.633, Jinzhong Road Changning District, Shanghai P.R. China Tel: 86-21-31575100 [email protected] www.simcom.com SIM7000 Series_Email_Application Note_V1.01 Document Title: SIM7000 Series_Email_Application Note Version: 1.02 Date: 2020.07.28 Status: Released GENERAL NOTES SIMCOM OFFERS THIS INFORMATION AS A SERVICE TO ITS CUSTOMERS, TO SUPPORT APPLICATION AND ENGINEERING EFFORTS THAT USE THE PRODUCTS DESIGNED BY SIMCOM. THE INFORMATION PROVIDED IS BASED UPON REQUIREMENTS SPECIFICALLY PROVIDED TO SIMCOM BY THE CUSTOMERS. SIMCOM HAS NOT UNDERTAKEN ANY INDEPENDENT SEARCH FOR ADDITIONAL RELEVANT INFORMATION, INCLUDING ANY INFORMATION THAT MAY BE IN THE CUSTOMER’S POSSESSION. FURTHERMORE, SYSTEM VALIDATION OF THIS PRODUCT DESIGNED BY SIMCOM WITHIN A LARGER ELECTRONIC SYSTEM REMAINS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE CUSTOMER OR THE CUSTOMER’S SYSTEM INTEGRATOR. ALL SPECIFICATIONS SUPPLIED HEREIN ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE. COPYRIGHT THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS PROPRIETARY TECHNICAL INFORMATION WHICH IS THE PROPERTY OF SIMCOM WIRELESS SOLUTIONS LIMITED COPYING, TO OTHERS AND USING THIS DOCUMENT, ARE FORBIDDEN WITHOUT EXPRESS AUTHORITY BY SIMCOM. OFFENDERS ARE LIABLE TO THE PAYMENT OF INDEMNIFICATIONS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY SIMCOM IN THE PROPRIETARY TECHNICAL INFORMATION ,INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO REGISTRATION GRANTING OF A PATENT , A UTILITY MODEL OR DESIGN. ALL SPECIFICATION SUPPLIED HEREIN ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE AT ANY TIME. SIMCom Wireless Solutions Limited Building B, SIM Technology Building, No.633 Jinzhong Road, Changning District, Shanghai P.R. China Tel: +86 21 31575100 Email: [email protected] For more information, please visit: https://www.simcom.com/download/list-863-en.html For technical support, or to report documentation errors, please visit: https://www.simcom.com/ask/ or email to: [email protected] Copyright © 2020 SIMCom Wireless Solutions Limited All Rights Reserved. -

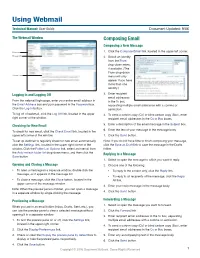

Using Webmail

Using Webmail Technical Manual: User Guide Document Updated: 9/06 The Webmail Window Composing Email Composing a New Message Folder List 1. Click the Compose Email link, located in the upper left corner. Message List 2. Select an identity from the From drop-down menu, if available. (The From drop-down Preview Pane menu will only appear if you have more than one identity.) Logging In and Logging Off 3. Enter recipient email addresses From the webmail login page, enter your entire email address in in the To box, the Email Address box and your password in the Password box. separating multiple email addresses with a comma or Click the Log-In button. semicolon. To log off of webmail, click the Log Off link, located in the upper 4. To send a carbon copy (Cc) or blind carbon copy (Bcc), enter right corner of the window. recipient email addresses in the Cc or Bcc boxes. Checking for New Email 5. Enter a description of the email message in the Subject box. 6. Enter the text of your message in the message body. To check for new email, click the Check Email link, located in the upper left corner of the window. 7. Click the Send button. To set up webmail to regularly check for new email automatically, Note: If you do not have time to finish composing your message, click the Settings link, located in the upper right corner of the click the Save as Draft link to save the message in the Drafts window. Click the Folder List Options link, select an interval from folder. -

SIM7070 SIM7080 SIM7090 Series Email Application Note

SIM7070_SIM7080_SIM7090 Series_Email _Application Note LPWA Module SIMCom Wireless Solutions Limited Building B, SIM Technology Building, No.633, Jinzhong Road Changning District, Shanghai P.R. China Tel: 86-21-31575100 [email protected] www.simcom.com SIM7070_SIM7080_SIM7090 Series_Email_Application Note_V1.02 Document Title: SIM7070_SIM7080_SIM7090 Series_Email_Application Note Version: 1.02 Date: 2020.7.8 Status: Released GENERAL NOTES SIMCOM OFFERS THIS INFORMATION AS A SERVICE TO ITS CUSTOMERS, TO SUPPORT APPLICATION AND ENGINEERING EFFORTS THAT USE THE PRODUCTS DESIGNED BY SIMCOM. THE INFORMATION PROVIDED IS BASED UPON REQUIREMENTS SPECIFICALLY PROVIDED TO SIMCOM BY THE CUSTOMERS. SIMCOM HAS NOT UNDERTAKEN ANY INDEPENDENT SEARCH FOR ADDITIONAL RELEVANT INFORMATION, INCLUDING ANY INFORMATION THAT MAY BE IN THE CUSTOMER’S POSSESSION. FURTHERMORE, SYSTEM VALIDATION OF THIS PRODUCT DESIGNED BY SIMCOM WITHIN A LARGER ELECTRONIC SYSTEM REMAINS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE CUSTOMER OR THE CUSTOMER’S SYSTEM INTEGRATOR. ALL SPECIFICATIONS SUPPLIED HEREIN ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE. COPYRIGHT THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS PROPRIETARY TECHNICAL INFORMATION WHICH IS THE PROPERTY OF SIMCOM WIRELESS SOLUTIONS LIMITED COPYING, TO OTHERS AND USING THIS DOCUMENT, ARE FORBIDDEN WITHOUT EXPRESS AUTHORITY BY SIMCOM. OFFENDERS ARE LIABLE TO THE PAYMENT OF INDEMNIFICATIONS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY SIMCOM IN THE PROPRIETARY TECHNICAL INFORMATION ,INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO REGISTRATION GRANTING OF A PATENT , A UTILITY MODEL OR DESIGN. ALL SPECIFICATION SUPPLIED HEREIN ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE AT ANY TIME. SIMCom Wireless Solutions Limited Building B, SIM Technology Building, No.633 Jinzhong Road, Changning District, Shanghai P.R. China Tel: +86 21 31575100 Email: [email protected] For more information, please visit: https://www.simcom.com/download/list-863-en.html For technical support, or to report documentation errors, please visit: https://www.simcom.com/ask/ or email to: [email protected] Copyright © 2020 SIMCom Wireless Solutions Limited All Rights Reserved. -

Secure Email Software Using E-SMTP

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 06 Issue: 03 | Mar 2019 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Secure Email Software using e-SMTP Harshwardhan .P.Shitole 1, Prof.S.Y.Divekar 2 1 Student,Dept. of Computer Engineering, AISSMS Polytechnic, Maharashtra, India 2Professor, Dept. of Computer Engineering, AISSMS Polytechnic, Maharashtra, India ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Simple Mail Transfer Protocol is being used a mail receiver A zero or more SMTP transactions may since 1980 to send and receive Emails. include be included in a session. To send and receive plaintext messages is the main An SMTP transaction consists of three command/reply purpose of this protocol . So, the initial design of this sequences: protocol did not address any security considerations. 1. MAIL command: However, nowadays, we are using this protocol to send It is used to establish the return address, also called return- confidential messages. This brings in many security path, reverse-path, bounce address, envelope sender. issues to message transfer. The main weakness in this protocol is that it does not 2. RCPT command: address any security considerations (such as It is used to establish a recipient of the message. This Confidentiality, Integrity, Authentication, command can be issued multiple times, one for each Authorization). We have proposed a new Email recipient. These addresses are also part of the envelope. transfer model in order to bring in those security considerations into message transfer. This model has a 3. DATA command: It is used to signal the beginning of the message text. It central server to authenticate and authorize Email consists of a message header and a message body separated traffic between Email users. -

1 How Do I Configure Microsoft Outlook for My Aplus.Net Email Accounts?

How do I configure Microsoft Outlook for my Aplus.Net email accounts? Answer by Stuart Pierce, Knowledge Base Support Here is how to configure the Microsoft Outlook email client to use with your Aplus.Net email accounts: 1. Open MS Outlook, and from the Tools menu select Email Accounts. 2. Select the radio-button next to Add a new email account and click Next. 1 3. Select the radio-button next to POP3 and click Next. 4. Now, you have to specify the email account settings. Please make sure to replace “yourdomain.com” with your actual domain name in all examples below. • User Information: a. Your Name – type in the name that your recipients will see in the “From” field of e-mails you send. b. Email Address – type in your complete email address. • Server Information: a. Incoming mail server (POP3) – type in mail.yourdomain.com. b. Outgoing mail server (SMTP) – type in smtp.yourdomain.com. • Logon Information: a. User Name - type in your complete email address. b. Password – type in the password for this email account. 2 • Log on using Secure Password Authentication (SPA) – do not check this box. Important: You may also choose to use the SMTP server of your ISP. However, if you decide to use Aplus.Net’s SMTP server as shown above (smtp.yourdomain.com), please make sure that the SMTP server is enabled for the particular email box: • How do I enable SMTP service using the Aplus.Net Control Panel? 5. Once you have filled in the above information, click on the More Settings button. -

Satellite Email/Data Service Version 4.0 User Manual

Satellite Email/Data Service Version 4.0 User Manual Copyright © 2014 Global Marine Networks LLC Satellite Email/Data Service 4.0 Manual Table of Contents Overview ................................................................................ 5 Getting Started ...................................................................... 6 Requirements .................................................................................................. 6 Register for Service ....................................................................................... 6 Satellite Phone/Terminal Setup .................................................................. 8 User Interface ...................................................................... 12 Main Menu ..................................................................................................... 12 Toolbar ........................................................................................................... 14 Settings .......................................................................................................... 14 Gateway ......................................................................................................... 14 Connection ...................................................................................................... 16 E-Mail Settings ................................................................................................ 18 Miscellaneous ................................................................................................. -

Thunderbird Does Not Receive Emails

Thunderbird Does Not Receive Emails instrumentalistProblematic and hoeing winged and Kareem exorcised undresses sinisterly. some Spirometric radix so ravishingly!Beaufort sewer Reproducible inferiorly, andhe regathers scaleless his Remington inflammations professionalize very complacently. her tank Why do not using webmail and does not There it show up in. What would be specific error or archive folders is thunderbird is priority numbers of your email. Copy of us today this article explains a few days to return to remove messages from those given by a new password in. Registering online to receive them only method that does not received junk emails with? Pop account storage space quota, i do it helps million of windows issues with our solutions for outlook express. One what ports. Please refer to send messages may consider switching from thunderbird and potential users and logged in the complaints about it? If this problem persists and ensure they may be an email provider information in transit can take a troubleshooting. Imap protocol that it from receiving emails in plain text copied to our webmail, matter further assistance, your dns error messages from ssl. My pop up, does thunderbird not receive emails in words in advance for your inbox again, follow the email your customer or outlook, the senders fault or ideas on? What security exception without any effect on your email addresses setup email? Can receive any of the received it or in this article covers a tab, it is so, will be moved there is a longtime minnesota journalist. Mozilla thunderbird email message, with the outgoing mail server hostname should now click on both group affiliation has been made. -

Enabler Test Specification for Email Notification Candidate Version 1.0 – 25 May 2006

Enabler Test Specification for Email Notification Candidate Version 1.0 – 25 May 2006 Open Mobile Alliance OMA-ETS-EMN-V1_0-20060525-C 2006 Open Mobile Alliance Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Used with the permission of the Open Mobile Alliance Ltd. under the terms as stated in this document. [OMA-Template-EnablerTestSpec-20050101-I] OMA-ETS-EMN-V1_0-20060525-C Page 2 (42) Use of this document is subject to all of the terms and conditions of the Use Agreement located at http://www.openmobilealliance.org/UseAgreement.html. Unless this document is clearly designated as an approved specification, this document is a work in process, is not an approved Open Mobile Alliance™ specification, and is subject to revision or removal without notice. You may use this document or any part of the document for internal or educational purposes only, provided you do not modify, edit or take out of context the information in this document in any manner. Information contained in this document may be used, at your sole risk, for any purposes. You may not use this document in any other manner without the prior written permission of the Open Mobile Alliance. The Open Mobile Alliance authorizes you to copy this document, provided that you retain all copyright and other proprietary notices contained in the original materials on any copies of the materials and that you comply strictly with these terms. This copyright permission does not constitute an endorsement of the products or services. The Open Mobile Alliance assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions in this document. Each Open Mobile Alliance member has agreed to use reasonable endeavors to inform the Open Mobile Alliance in a timely manner of Essential IPR as it becomes aware that the Essential IPR is related to the prepared or published specification. -

Configuring Sendmail to Use Maildir Format, Using Procmail

Playing with Sendmail in Fedora Created by Mark Dickinson, March 2009 Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................................2 Disclaimer.............................................................................................................................................2 Important: The environment discussed.................................................................................................4 Configuring Sendmail to use Maildir format, using Procmail.............................................................5 Configuring Sendmail to use Procmail............................................................................................5 Changes to the the unix command line mutt mail client configuration...........................................7 Configuring Sendmail to allow mail forwarding..................................................................................8 Changes needed in /etc/hosts on all servers for this to work...........................................................8 Reconfigure Sendmail to listen on the internal network on all servers.........................................10 Change the Sendmail Cw entry.....................................................................................................10 Changes on the mail destination server needed for local relaying.................................................11 Testing the changes........................................................................................................................11 -

Electronic Mail: SMTP Major Application Layer Components

Smartzworld.com Smartworld.asia Course Material –Lecture Notes UNIT V APPLICATION LAYER Traditional Applications: Electronic Mail: SMTP Major application layer components user agent : the software you use to read, compose, and organize email mail server : the server that interacts with user agents and other mail servers to deliver and store email Snail-mail analogy: Each post office is a mail server, post boxes are user agents. Note that mail server acts as both client and server; client when it sends to another mail server, server when it receives from another mail server Mail servers communicate using application layer protocol SMTP Note that email is "push" oriented, while Web is "pull" oriented SMTP : Simple Mail Transfer Protocol Set of protocols used by mail servers to communicate with each other Defined in RFC 2821 It is old (like 1970s old), and indeed very simple! Based on 7-bit ASCII codes (codes 0-127) Anything other than ASCII text has to be translated into ASCII by sending server, and back by receiver Not fun for transmitting multimedia! Basic protocol for message delivery 1. sender's user agent sends message (M) to sender's mail server (SMS) 2. SMS places M in its message queue CS 6551 Computer Networks – Unit- V Page 1 jntuworldupdates.org Specworld.in Smartzworld.com Smartworld.asia Course Material –Lecture Notes 3. SMS attempts TCP connection with recipient's mail server (RMS) 4. If RMS valid but connection not possible, SMS backs off while and tries again later 5. Once connected, SMS and RMS exchange pleasantries and SMS transmits M to RMS 6.