Topic 2670 Solubilities of Gases in Liquids Comparison of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Body Temperature & Pressure, Saturated” & Ambient Pressure Correction in Air Medical Transport

“Body Temperature & Pressure, Saturated” & Ambient Pressure Correction in air medical transport Mechanical ventilation can be especially challenging during air medical transport, particularly due to the impact of varying atmospheric pressure with changing altitudes. The Oxylog® 3000 plus and Oxylog® 2000 plus help to effectively deal with these challenges. D-33481-2011 Artificial ventilation uses compressed the ventilation volumes delivered by the gas to deliver the required volume to the ventilator. Mechanical ventilation in fixed patient. This breathing gas has normally wing aircraft without a pressurized cabin an ambient temperature level and is very is subject to the same dynamics. In case dry. Inside the human lungs the gas of a pressurized cabin it is still relevant expands due to a higher temperature and to correct the inspiratory volumes, as humidity level. These physical conditions the cabin is usually maintained at MT-5809-2008 are described as “Body Temperature & a pressure of approximately 800 mbar Figure 1: Oxylog® 3000 plus Pressure, Saturated” (BTPS), which (600 mmHg), comparable to an altitude The Oxylog® 3000 plus automatically com- presumes the combined environmental of 8,200 ft/2,500 m. pensates volume delivery and measurement circumstances of – Without BTPS correction, the deli- – a body temperature of 37 °C / 99 °F vered inspiratory volume can deviate up – ambient barometrical pressure to 14 % conditions and (at 14,800 ft/4,500 m altitude) from – breathing gas saturated with water the targeted set volume (i.e. 570 ml vapour (= 100 % relative humidity). instead of 500 ml). – Without ambient pressure correction, Aside from the challenge of changing the inspiratory volume can deviate up temperatures and humidity inside the to 44 % (at 14,800 ft/4,500 m altitude) patient lungs, the ambient pressure is from the targeted set volume also important to consider. -

Page 1 of 6 This Is Henry's Law. It Says That at Equilibrium the Ratio of Dissolved NH3 to the Partial Pressure of NH3 Gas In

CHMY 361 HANDOUT#6 October 28, 2012 HOMEWORK #4 Key Was due Friday, Oct. 26 1. Using only data from Table A5, what is the boiling point of water deep in a mine that is so far below sea level that the atmospheric pressure is 1.17 atm? 0 ΔH vap = +44.02 kJ/mol H20(l) --> H2O(g) Q= PH2O /XH2O = K, at ⎛ P2 ⎞ ⎛ K 2 ⎞ ΔH vap ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = ln⎜ ⎟ − ⎜ − ⎟ equilibrium, i.e., the Vapor Pressure ⎝ P1 ⎠ ⎝ K1 ⎠ R ⎝ T2 T1 ⎠ for the pure liquid. ⎛1.17 ⎞ 44,020 ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = − ⎜ − ⎟ = 1 8.3145 ⎜ T 373 ⎟ ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ 2 ⎠ ⎡1.17⎤ − 8.3145ln 1 ⎢ 1 ⎥ 1 = ⎣ ⎦ + = .002651 T2 44,020 373 T2 = 377 2. From table A5, calculate the Henry’s Law constant (i.e., equilibrium constant) for dissolving of NH3(g) in water at 298 K and 340 K. It should have units of Matm-1;What would it be in atm per mole fraction, as in Table 5.1 at 298 K? o For NH3(g) ----> NH3(aq) ΔG = -26.5 - (-16.45) = -10.05 kJ/mol ΔG0 − [NH (aq)] K = e RT = 0.0173 = 3 This is Henry’s Law. It says that at equilibrium the ratio of dissolved P NH3 NH3 to the partial pressure of NH3 gas in contact with the liquid is a constant = 0.0173 (Henry’s Law Constant). This also says [NH3(aq)] =0.0173PNH3 or -1 PNH3 = 0.0173 [NH3(aq)] = 57.8 atm/M x [NH3(aq)] The latter form is like Table 5.1 except it has NH3 concentration in M instead of XNH3. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS Introductory Information C

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS Introductory Information C. L. Young, R. Battino, and H. L. Clever INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the literature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uniform format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of sufficient accuracy are available values are recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation is given to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are published on consecutive pages. The following paper by E. Wilhelm gives a rigorous thermodynamic treatment on the solubility of gases in liquids. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solubility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas-liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solubility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the criti cal temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solubility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the particular worker concerned. -

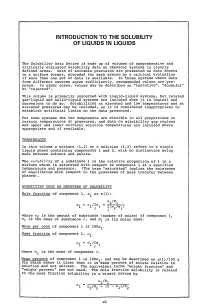

Introduction to the Solubility of Liquids in Liquids

INTRODUCTION TO THE SOLUBILITY OF LIQUIDS IN LIQUIDS The Solubility Data Series is made up of volumes of comprehensive and critically evaluated solubility data on chemical systems in clearly defined areas. Data of suitable precision are presented on data sheets in a uniform format, preceded for each system by a critical evaluation if more than one set of data is available. In those systems where data from different sources agree sufficiently, recommended values are pro posed. In other cases, values may be described as "tentative", "doubtful" or "rejected". This volume is primarily concerned with liquid-liquid systems, but related gas-liquid and solid-liquid systems are included when it is logical and convenient to do so. Solubilities at elevated and low 'temperatures and at elevated pressures may be included, as it is considered inappropriate to establish artificial limits on the data presented. For some systems the two components are miscible in all proportions at certain temperatures or pressures, and data on miscibility gap regions and upper and lower critical solution temperatures are included where appropriate and if available. TERMINOLOGY In this volume a mixture (1,2) or a solution (1,2) refers to a single liquid phase containing components 1 and 2, with no distinction being made between solvent and solute. The solubility of a substance 1 is the relative proportion of 1 in a mixture which is saturated with respect to component 1 at a specified temperature and pressure. (The term "saturated" implies the existence of equilibrium with respect to the processes of mass transfer between phases) • QUANTITIES USED AS MEASURES OF SOLUBILITY Mole fraction of component 1, Xl or x(l): ml/Ml nl/~ni = r(m.IM.) '/. -

2007 MTS Overview of Manned Underwater Vehicle Activity

P A P E R 2007 MTS Overview of Manned Underwater Vehicle Activity AUTHOR ABSTRACT William Kohnen There are approximately 100 active manned submersibles in operation around the world; Chair, MTS Manned Underwater in this overview we refer to all non-military manned underwater vehicles that are used for Vehicles Committee scientific, research, tourism, and commercial diving applications, as well as personal leisure SEAmagine Hydrospace Corporation craft. The Marine Technology Society committee on Manned Underwater Vehicles (MUV) maintains the only comprehensive database of active submersibles operating around the world and endeavors to continually bring together the international community of manned Introduction submersible operators, manufacturers and industry professionals. The database is maintained he year 2007 did not herald a great through contact with manufacturers, operators and owners through the Manned Submersible number of new manned submersible de- program held yearly at the Underwater Intervention conference. Tployments, although the industry has expe- The most comprehensive and detailed overview of this industry is given during the UI rienced significant momentum. Submersi- conference, and this article cannot cover all developments within the allocated space; there- bles continue to find new applications in fore our focus is on a compendium of activity provided from the most dynamic submersible tourism, science and research, commercial builders, operators and research organizations that contribute to the industry and who share and recreational work; the biggest progress their latest information through the MTS committee. This article presents a short overview coming from the least likely source, namely of submersible activity in 2007, including new submersible construction, operation and the leisure markets. -

Chapter 15: Solutions

452-487_Ch15-866418 5/10/06 10:51 AM Page 452 CHAPTER 15 Solutions Chemistry 6.b, 6.c, 6.d, 6.e, 7.b I&E 1.a, 1.b, 1.c, 1.d, 1.j, 1.m What You’ll Learn ▲ You will describe and cate- gorize solutions. ▲ You will calculate concen- trations of solutions. ▲ You will analyze the colliga- tive properties of solutions. ▲ You will compare and con- trast heterogeneous mixtures. Why It’s Important The air you breathe, the fluids in your body, and some of the foods you ingest are solu- tions. Because solutions are so common, learning about their behavior is fundamental to understanding chemistry. Visit the Chemistry Web site at chemistrymc.com to find links about solutions. Though it isn’t apparent, there are at least three different solu- tions in this photo; the air, the lake in the foreground, and the steel used in the construction of the buildings are all solutions. 452 Chapter 15 452-487_Ch15-866418 5/10/06 10:52 AM Page 453 DISCOVERY LAB Solution Formation Chemistry 6.b, 7.b I&E 1.d he intermolecular forces among dissolving particles and the Tattractive forces between solute and solvent particles result in an overall energy change. Can this change be observed? Safety Precautions Dispose of solutions by flushing them down a drain with excess water. Procedure 1. Measure 10 g of ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and place it in a Materials 100-mL beaker. balance 2. Add 30 mL of water to the NH4Cl, stirring with your stirring rod. -

Optimal Breathing Gas Mixture in Professional Diving with Multiple Supply

Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering 2021 WCE 2021, July 7-9, 2021, London, U.K. Optimal Breathing Gas Mixture in Professional Diving with Multiple Supply Orhan I. Basaran, Mert Unal compressors and cylinders, it was limited to surface air Abstract— Professional diving existed since antiquities when supply lines. In 1978, Fleuss introduced the first closed divers collected resources from the bottom of the seas and circuit oxygen breathing apparatus which removed carbon lakes. With technological advancements in the recent century, dioxide from the exhaled gas and did not form bubbles professional diving activities also increased significantly. underwater. In 1943, Cousteau and Gangan designed the Diving has many adverse effects on human physiology which first proper demand-regulated air supply from compressed are widely investigated in order to make dives safer. In this air cylinders worn on the back. The scuba equipment with study, we focus on optimizing the breathing gas mixture minimizing the dive costs while ensuring the safety of the the high-pressure regulator on the cylinder and a single hose divers. The methods proposed in this paper are purely to a demand valve was invented in Australia and marketed theoretical and divers should always have appropriate training by Ted Eldred in the early 1950s [1]. and certificates. Also, divers should never perform dives With the use of Siebe dress, the first cases of decompression without consulting professionals and medical doctors with expertise in related fields. sickness began to be documented. Haldane conducted several experiments on animal and human subjects in Index Terms—-professional diving; breathing gas compression chambers to investigate the causes of this optimization; dive profile optimization sickness and how it can be prevented. -

Ocean Storage

277 6 Ocean storage Coordinating Lead Authors Ken Caldeira (United States), Makoto Akai (Japan) Lead Authors Peter Brewer (United States), Baixin Chen (China), Peter Haugan (Norway), Toru Iwama (Japan), Paul Johnston (United Kingdom), Haroon Kheshgi (United States), Qingquan Li (China), Takashi Ohsumi (Japan), Hans Pörtner (Germany), Chris Sabine (United States), Yoshihisa Shirayama (Japan), Jolyon Thomson (United Kingdom) Contributing Authors Jim Barry (United States), Lara Hansen (United States) Review Editors Brad De Young (Canada), Fortunat Joos (Switzerland) 278 IPCC Special Report on Carbon dioxide Capture and Storage Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 279 6.7 Environmental impacts, risks, and risk management 298 6.1 Introduction and background 279 6.7.1 Introduction to biological impacts and risk 298 6.1.1 Intentional storage of CO2 in the ocean 279 6.7.2 Physiological effects of CO2 301 6.1.2 Relevant background in physical and chemical 6.7.3 From physiological mechanisms to ecosystems 305 oceanography 281 6.7.4 Biological consequences for water column release scenarios 306 6.2 Approaches to release CO2 into the ocean 282 6.7.5 Biological consequences associated with CO2 6.2.1 Approaches to releasing CO2 that has been captured, lakes 307 compressed, and transported into the ocean 282 6.7.6 Contaminants in CO2 streams 307 6.2.2 CO2 storage by dissolution of carbonate minerals 290 6.7.7 Risk management 307 6.2.3 Other ocean storage approaches 291 6.7.8 Social aspects; public and stakeholder perception 307 6.3 Capacity and fractions retained -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

Chemistry C3102-2006: Polymers Section Dr. Edie Sevick, Research School of Chemistry, ANU 5.0 Thermodynamics of Polymer Solution

Chemistry C3102-2006: Polymers Section Dr. Edie Sevick, Research School of Chemistry, ANU 5.0 Thermodynamics of Polymer Solutions In this section, we investigate the solubility of polymers in small molecule solvents. Solubility, whether a chain goes “into solution”, i.e. is dissolved in solvent, is an important property. Full solubility is advantageous in processing of polymers; but it is also important for polymers to be fully insoluble - think of plastic shoe soles on a rainy day! So far, we have briefly touched upon thermodynamic solubility of a single chain- a “good” solvent swells a chain, or mixes with the monomers, while a“poor” solvent “de-mixes” the chain, causing it to collapse upon itself. Whether two components mix to form a homogeneous solution or not is determined by minimisation of a free energy. Here we will express free energy in terms of canonical variables T,P,N , i.e., temperature, pressure, and number (of moles) of molecules. The free energy { } expressed in these variables is the Gibbs free energy G G(T,P,N). (1) ≡ In previous sections, we referred to the Helmholtz free energy, F , the free energy in terms of the variables T,V,N . Let ∆Gm denote the free eneregy change upon homogeneous mix- { } ing. For a 2-component system, i.e. a solute-solvent system, this is simply the difference in the free energies of the solute-solvent mixture and pure quantities of solute and solvent: ∆Gm G(T,P,N , N ) (G0(T,P,N )+ G0(T,P,N )), where the superscript 0 denotes the ≡ 1 2 − 1 2 pure component. -

Gp-Cpc-01 Units – Composition – Basic Ideas

GP-CPC-01 UNITS – BASIC IDEAS – COMPOSITION 11-06-2020 Prof.G.Prabhakar Chem Engg, SVU GP-CPC-01 UNITS – CONVERSION (1) ➢ A two term system is followed. A base unit is chosen and the number of base units that represent the quantity is added ahead of the base unit. Number Base unit Eg : 2 kg, 4 meters , 60 seconds ➢ Manipulations Possible : • If the nature & base unit are the same, direct addition / subtraction is permitted 2 m + 4 m = 6m ; 5 kg – 2.5 kg = 2.5 kg • If the nature is the same but the base unit is different , say, 1 m + 10 c m both m and the cm are length units but do not represent identical quantity, Equivalence considered 2 options are available. 1 m is equivalent to 100 cm So, 100 cm + 10 cm = 110 cm 0.01 m is equivalent to 1 cm 1 m + 10 (0.01) m = 1. 1 m • If the nature of the quantity is different, addition / subtraction is NOT possible. Factors used to check equivalence are known as Conversion Factors. GP-CPC-01 UNITS – CONVERSION (2) • For multiplication / division, there are no such restrictions. They give rise to a set called derived units Even if there is divergence in the nature, multiplication / division can be carried out. Eg : Velocity ( length divided by time ) Mass flow rate (Mass divided by time) Mass Flux ( Mass divided by area (Length 2) – time). Force (Mass * Acceleration = Mass * Length / time 2) In derived units, each unit is to be individually converted to suit the requirement Density = 500 kg / m3 . -

Topic720 Composition: Mole Fraction: Molality: Concentration a Solution Comprises at Least Two Different Chemical Substances

Topic720 Composition: Mole Fraction: Molality: Concentration A solution comprises at least two different chemical substances where at least one substance is in vast molar excess. The term ‘solution’ is used to describe both solids and liquids. Nevertheless the term ‘solution’ in the absence of the word ‘solid’ refers to a liquid. Chemists are particularly expert at identifying the number and chemical formulae of chemical substances present in a given closed system. Here we explore how the chemical composition of a given system is expressed. We consider a simple system prepared using water()l and urea(s) at ambient temperature and pressure. We designate water as chemical substance 1 and urea as chemical substance j, so that the closed system contains an aqueous solution. The amounts of the two substances are given by n1 = = ()wM11 and nj ()wMjj where w1 and wj are masses; M1 and Mj are the molar masses of the two chemical substances. In these terms, n1 and nj are extensive variables. = ⋅ + ⋅ Mass of solution, w n1 M1 n j M j (a) = ⋅ Mass of solvent, w1 n1 M1 (b) = -1 For water, M1 0.018 kg mol . However in reviewing the properties of solutions, chemists prefer intensive composition variables. Mole Fraction The mole fractions of the two substances x1 and xj are given by the following two equations: =+ =+ xnnn111()j xnnnjj()1 j (c) += Here x1 x j 10. In general terms for a system comprising i - chemical substances, the mole fraction of substance k is given by equation (d). ji= = xnkk/ ∑ n j (d) j=1 ji= = Hence ∑ x j 10.